Science communication: You sabi say nobi evri bodi sabi speak did oyibo, Yen nyinaa enka brofo!

In recognition of International Mother Language Day, Nigel Paul reflects on the experience of the RECIRCULATE team in addressing the challenge of science communication to stakeholders in their own language.

Over recent months RECIRCULATE and its sister-projects have highlighted several “International days” relevant to our projects, and there are more to come. 8th March is International Women’s Day, 22nd March is World Water Day, 21st April is World Creativity and Innovation Day and 5th June is World Environment Day. All of these obviously fit with the scope and ambitions of the projects, but I must admit that at first sight I wondered about International Mother Language Day, which is this Sunday, 21st February. I could not have been more wrong! Now that I have thought about it, and listened to colleagues from across the project, I realise that this day, and the topic it highlights, is at the heart of delivering our aim of researchers working “with, in and for their communities”.

That may well be far more obvious to you than it was to me. That in itself raises an important question- why had I missed such an important point? I suspect that’s down to me being in the lucky position of English- my own mother language- being the globally accepted ‘language of science’. That certainly makes life easy! Beyond that, if you’ll excuse the self-reflection, I’m horrified with myself for missing this when I’d always thought I was quite aware of the challenges of “science communication”. What that meant was that I realise that researchers easily forget that few people speak ‘our language’. Anyone reading a scientific paper realises that we love the technical terms, abbreviations, acronyms and even a particular writing style that applies to our subject. We’ve spent a lot of time learning all that, and we need show our colleagues we can ‘speak their language’. OK, that may be our colleagues, but for everyone else what we say, or write, risks becoming an alphabet soup of meaningless jargon. That’s hardly news. It’s a point that has been picked up in several other blogs in The FLOW, in the PARTICIPATE webinar on communication, and in discussions in the project WhatsApp group. We know the problem, and many are trying to find solutions but have some of us thought about it too narrowly in terms of explaining our research in non-technical English rather than in other languages?

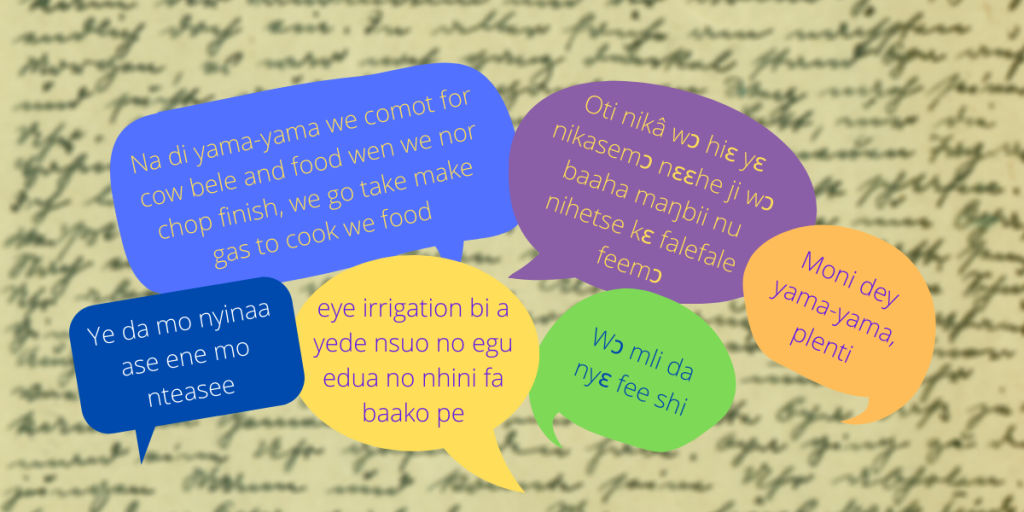

That’s the step that I had missed, but which became obvious once I’d listened to colleagues at our front-line of working “with, in and for their communities”. Their hands-on experience offer tremendous insights. Sometimes, the key step is ‘translating’ a scientific concept in to non-technical language, whatever the mother language that’s expressed in. Chris Emokaro from UniBEN explains anaerobic digestion in Nigerian pidgin as “Na di yama-yama we comot for cow bele and food wen we nor chop finish, we go take make gas to cook we food”. Chris has both translated the concept- anaerobic digestion becomes “Food waste and cattle rumen content would be digested for use as cooking gas”- and then expressed the concept in pidgin. Kwadwo Ansong Asante from CSIR’s Water Research Institute takes a similar two-step approach when explaining “Water for Sanitation and Health” to Ga-speaking communities in Accra as “Otinikâ wɔ hiɛ yɛ nikasemɔ nɛɛhe ji wɔ baaha maŋbii nu nihetse kɛ falefale feemɔ” or, in English, “We are undertaking the project to ensure good drinking water and environmental cleanliness”.

Patricia Oteng-Darko from CSIR’s Crops Research Institute in Kumasi also described a similar “double translation” when explaining partial root-zone drying, which becomes “eye irrigation bi a yede nsuo no egu edua no nhini fa baako pe” in Asante Twi. The literal English translation is ‘it is a type of irrigation technology whereby water is applied to only one side of the plants rootzone’. Patricia goes on to note that “…. sometimes we struggle to get the exact word to word translation and may end up using the best words that can carry the ideas and concepts along. There have also been instances where the farmers themselves pitch in the mother language to support our explanations of certain terminologies or concepts.”

Patricia’s colleague Stephen Yeboah also makes clear that translation isn’t simply about the words “In one of our community engagements, we wanted to explain water table height….. 30cm was explained as “basafa” a local language meaning “half of your hand”. Like Patricia, Stephen also emphasises that this is a genuine dialogue. “ We wanted to get the local name for bees, after identifying the importance of bees in crop production the farmers referred to it as ‘Crop Kunu‘. Kunu in our local dialect means ‘husband’”. As Stephen notes, this link between bees and husbands emerges from the role of men in the home in local communities. That highlights that the challenge here is sometimes translation across cultures, not just across languages, what Stephen refers to the “Africanization of science”.

These are clearly profound issues for a project aspiring not just to ‘do’ research but also communicate it “with, in and for their communities”. It’s equally clear that there is deep expertise across the project that we can all learn from, within the project and beyond. The recent discussion is the Whatsapp group showed further insights- and real passion- on the topic. It would be great to hear more about your first-hand experience- more blogs very welcome! I can borrow one of Asante’s translations in to Twi: “Ye da mo nyinaa ase ene mo nteasee”- thank you all for your co-operation.

The need to share this experience is clear from the challenge that the Mother Language Day website gives us. It states, “This year’s observance is a call on policymakers, educators and teachers, parents and families to scale up their commitment to multilingual education, and inclusion….” Maybe we need to add ‘researchers’ to that list? That would certainly fit with the overall arching description of the day. “International Mother Language Day recognizes that languages and multilingualism can advance inclusion and the Sustainable Development Goals’ focus on leaving no one behind.” Isn’t inclusion just what we mean by research “…. with, in and for their communities”?

RECIRCULATE network members holding up signs with the phrase “Go with the flow” translated into their mother languages.

Here is a summary of all quotes and their translation in English:

| “You sabi say nobi evri bodi sabi speak did oyibo!” | “Remember, we don’t all speak English!” |

| “Yen nyinaa enka brofo!” | “Remember, we don’t all speak English!” |

| “Na di yama-yama we comot for cow bele and food wen we nor chop finish, we go take make gas to cook we food” | “Food waste and cattle rumen content would be digested for use as cooking gas” |

| “Otinikâ wɔ hiɛ yɛ nikasemɔ nɛɛhe ji wɔ baaha maŋbii nu nihetse kɛ falefale feemɔ” | “We are undertaking the project to ensure good drinking water and environmental cleanliness” |

| “Eye irrigation bi a yede nsuo no egu edua no nhini fa baako pe” | “It is a type of irrigation technology whereby water is applied to only one side of the plants rootzone” |

| “Ye da mo nyinaa ase ene mo nteasee” | “Thank you all for your co-operation” |

| “Moni dey yama-yama, plenti” | “There is so much wealth in waste” |

| “Wɔ mli da nyɛ fee shi” | “We thank you all for your co-operation and understanding” |

| “Crop Kunu” | “Bees” |

| “Basafa” | “Half of your hand” |

|

Professor Nigel Paul is a plant scientist at Lancaster University, UK. He was RECIRCULATE’s first director and moved to become the editor of The Flow as part of winding-down towards retirement. Nigel has a BSc from Reading University, UK and a PhD from University of Lancaster, UK. He has worked in university research, teaching and management for almost 40 years. |

All articles in The FLOW are published under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives license, for details please read the RECIRCULATE re-publishing guidelines.