Here are a number of articles and books arising from Lancaster University’s research into the social effects of flooding and children’s role in Disaster Risk Reduction:

This book, produced by the CUIDAR project team, argues for a radical transformation in children’s roles and voices in disasters. It shows practitioners, policy-makers and researchers how more child-centred disaster management, that recognises children’s capacity to enhance disaster resilience, actually benefits at-risk communities as a whole.

Our case study features in this publication to guide experts and policymakers, technical working groups, international and non-governmental organisations in their work to reduce disaster risk and build resilience.

This article is aimed at emergency managers, public health practitioners, policymakers, journalists and others who can implement and amplify the findings from our disaster research with children.

This paper draws on case studies of several of the children and young people we worked with during the Children, Young People and Flooding project to discuss how flooding causes multiple losses and affects children’s relationship with place and space.

This article draws on our Children, Young People and Flooding project report to make a case for including children and young people in policymaking in UK flood risk management.

- Easthope, L. (2018). The Recovery Myth: The Plans and Situated Realities of Post Disaster Response. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

This book provides an innovative re-examination of the ‘recovery’ phase of a disaster. Drawing on two decades’ of work, the book develops an ethnography of the residents and responders in one flooded village and applies this to other cases of UK flooding, as well as to post-disaster recovery in New Zealand. The book shows how localised emergency responders find ways to collaborate with residents, and how an informal network uses nationally generated instruments differently to co-produce regeneration within a community. The book considers the plethora of government instruments which have been produced to affect recovery, including checklists, templates and guidance documents, and discusses approaches to community resilience and recovery risk management.

- Lloyd Williams, A., Bingley, A., Walker, M., Mort, M., & Howells, V. (2017). “That’s where I first saw the water…”: mobilizing children’s voices in UK flood risk management. Transfers: Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies 7:3, pp.76-93.

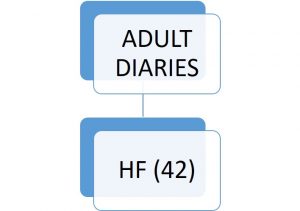

This paper brings together the interdisciplines of performance studies, disaster studies and mobilities studies to argue that flood-affected children can mobilise and be mobilised by performance-based methods. We suggest that these methods help children’s voices to ‘travel’ and support them to become change agents in disaster planning.

- Medd, W., Deeming, H., Walker, G., Whittle, R., Mort, M., Twigger-Ross, C., Walker, M., Watson, N., & Kashefi, E. (2015). The flood recovery gap: a real-time study of local recovery following the floods of June 2007 in Hull, North East England. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 8:4, pp.315-328.

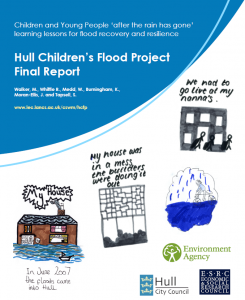

This paper reports on the findings of a longitudinal study using an action research model to understand the everyday experiences of individuals following the floods of June 2007 in Hull. The research shows that what happens after a flood in terms of getting your life and your home back on track is often harder for people to deal with than the event itself. The paper argues that recovery involves a more varied process than is assumed and concludes with suggestions for addressing the ‘recovery gap’.

Recovery practices following the loss of home, sense of security, space and possessions, have recently become a focus of government attention. How people recover from disasters is seen to have a direct bearing on individual, community and economic well-being. A raft of instruments: templates, checklists and guidance documents have been produced to instigate recovery, which work within a wider context of disaster planning to create order where much is uncertain, reactive and dependent on emerging relationships. While such instruments are not necessarily unwelcome, they carry many assumptions. We show how they are built from official narratives that are often remote from situated practices or recovery-in-place. From a five-year study of a flooded community in South Yorkshire and the development of government recovery guidance, it became clear that such protocols became transformed locally when enacted by newly formed collaborations of residents and local responders. In this way, operating alongside, and sometimes underneath the official response, residents and local responders demonstrated a remaking of the politics of recovery.

- Whittle, R., Medd, W., Mort, M., Deeming, H., Walker, M., Twigger-Ross, C., Walker, G. & Watson, N. (2014). Placing the flood recovery process. In: I. Convery, G. Corsane & P. Davis (Eds). Displaced Heritage – Responses to Disaster, Trauma and Loss. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, pp. 199-206, ISBN: 9781843839637.

This chapter ‘Placing the flood recovery process’ is part of the section looking at ‘Displaced Heritage: Lived Realities, Local Experiences’. The chapter reports on the findings of the longitudinal study of people’s recovery from the floods of June 2007 in Kingston-upon-Hull, UK in which over 8,600 households were affected. The chapter begins by exploring the ways in which the policy and research literature describes the recovery process, and then moves on to the experiences of the Hull residents. It argues that if we want to understand the recovery process then it is essential to think about what it is that is being recovered.

- Walker, M., Whittle, R., Medd, W., Burningham, K., Moran-Ellis, J. & Tapsell, S. (2012). ‘It came up to here’: learning from children’s flood narratives. Children’s Geographies, 10:2, pp.135-150.

The growing body of literature that seeks to understand the social impact of flooding has failed to recognise the value of children’s knowledge in understanding the impact of flood. This paper argues, through a case study with flood-affected children in Hull, the significance of children’s accounts. More specifically the paper identifies first, how children have specific flood experiences that need to be understood in their own right, and second, how through children’s accounts we can understand more about the nature of flood and the flood recovery process.

This paper uses concepts of emotion work and emotional labour to explore people’s experiences of the long-term disaster recovery process. It draws on data taken from two qualitative research projects which looked at adults’ and children’s recovery from the floods of June 2007 in Hull, UK. The paper argues that the emotional work of recovery cannot be separated from the physical and practical work of recovering the built environment. It shows that a focus on emotion work can lead to a more nuanced understanding of what recovery actually means and who is involved, leading to the identification of hidden vulnerabilities and a better understanding of the longer timescales involved in the process.

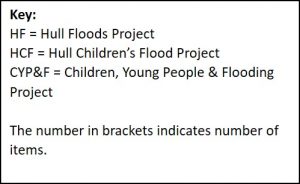

Dissemination is a vital but neglected component of research with children. Drawing on our experiences working with 46 flood-affected children and young people we evaluate the evolution of a creative methodology for disseminating research results to non-academic audiences in tandem with the participants. Reflecting on the strengths and weaknesses of this process, we highlight three key conclusions: the importance of reciprocity in research, the necessity of taking a creative, active approach to dissemination, and the role of dissemination in providing a means by which other issues can be explored.

This paper approaches flooding as a socio-natural-technical assemblage, a phenomenon that comes into being in relation to the spaces that `bad water’ occupies. We use the case of the major flood in the city of Hull in June 2007, and the accounts of those who experienced it, to follow the flood water into homes and household spaces. Through the analysis of data from two parallel projects examining the experiences of adults and children, we show that the boundaries of the flood remained open, contested and socially complex. Finally, implications are explored in relation to the processes embroiled in producing ‘flood status’ and the consequences for the actors involved.

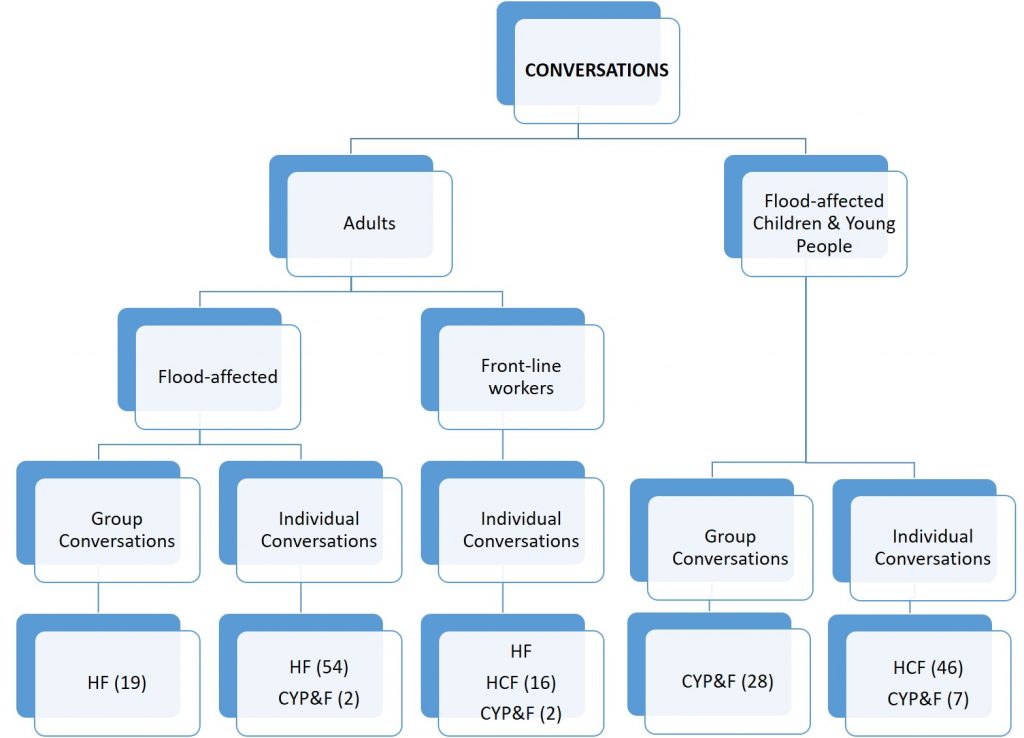

This article is based on a case study of the summer floods of June 2007 in Hull, Northeast England. We use a real-time, diary-based methodology to document and understand the everyday experiences of individuals following the floods. We ask what can we can learn about caring when the home is disrupted. Focusing on the diaries, we explore what flood reveals about the emotional and physical landscapes of caring in the context of recovery and illustrate the intimate connections that exist between ideas of dwelling and caring. In drawing on the accounts of carers (who are often also those displaced by flood), we explore the tensions between, and intersections of spaces of care work as these are enacted between the routines of everyday ‘normal’ life and the specific disruptions generated by flood.

- Watkins, S. & Whyte, I. (2009). Floods in North West England: a history c. 1600-2008. Lancaster University: Centre for North-West Regional Studies.

Mort, M., Walker, M., Lloyd Williams, A., Bingley, A. & Howells, V. (2016).

Mort, M., Walker, M., Lloyd Williams, A., Bingley, A. & Howells, V. (2016).

Walker, M., Whittle R., Medd, W., Burningham, K., Moran-Ellis, J. & Tapsell, S. (2011).

Walker, M., Whittle R., Medd, W., Burningham, K., Moran-Ellis, J. & Tapsell, S. (2011). Whittle, R., Medd, W., Deeming, H., Kashefi, E., Mort, M., Twigger Ross, C., Walker, G. & Watson, N. (2010).

Whittle, R., Medd, W., Deeming, H., Kashefi, E., Mort, M., Twigger Ross, C., Walker, G. & Watson, N. (2010).