Here you will explore:

- what is meant by ‘data’

- where and how data collection fits into the process of working with flood-affected communities

- different methods you can use to work with flood-affected people and the types of data that these will produce, e.g. audio recordings of people speaking, drawings, photographs etc.

What is ‘data’? Data is any material that gets collected or contributed by flood-affected people, who are very often concerned to help others who may go through similar experiences, or to help policy and practice better understand what being flooded means. If during your work you want to take photographs, audio and video recordings or collect other forms of written or creative material you will need to think about the ethics of how you collect, store and use this material. You should also consider how different ways of working will generate different types of data.

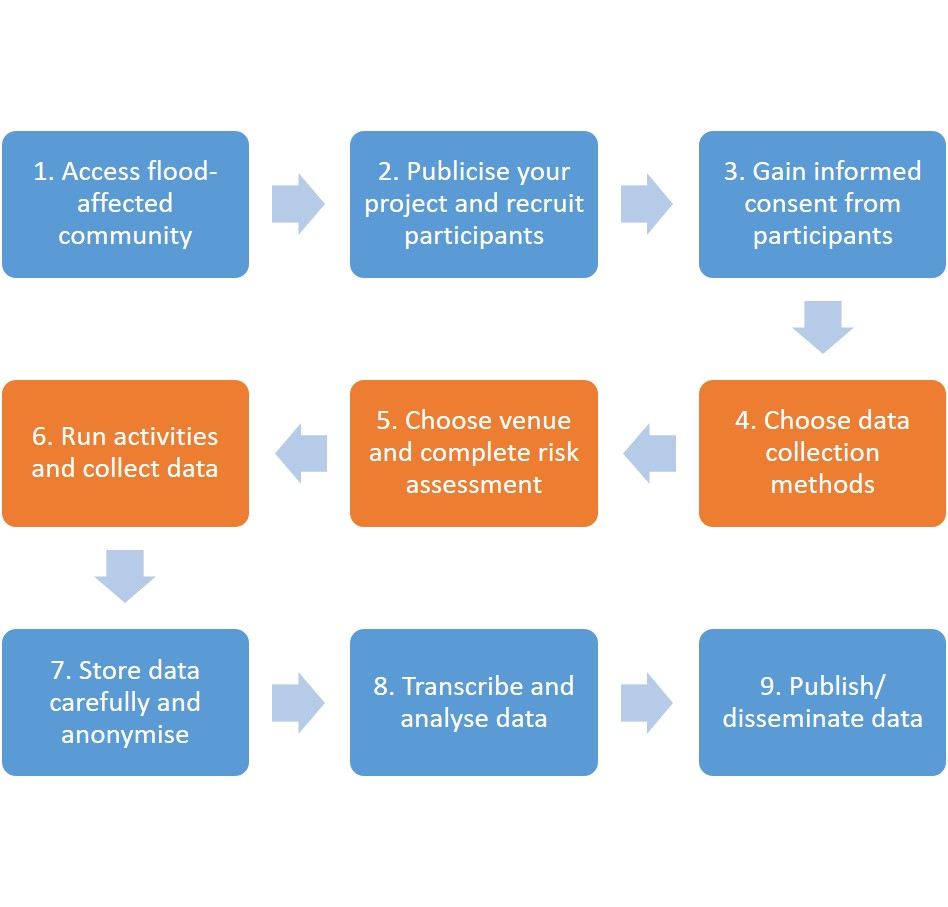

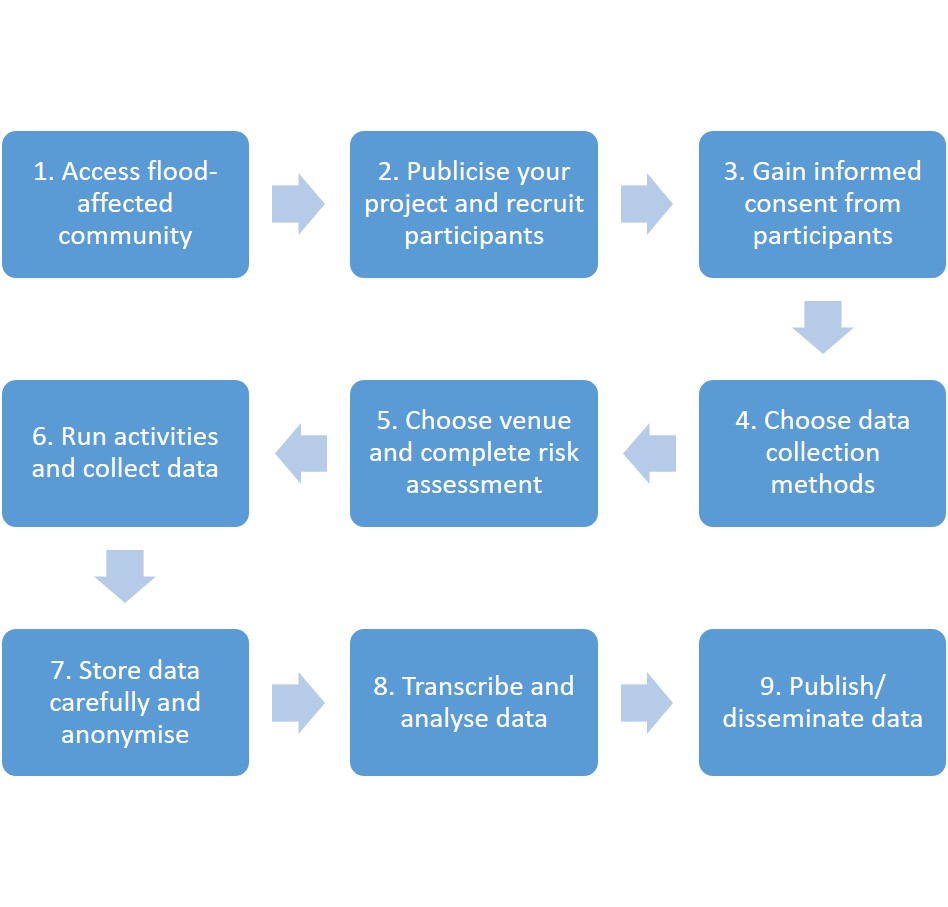

Where data collection fits into the process of working with flood-affected communities

Before you begin! Before starting to work with flood-affected communities, you need to have carefully set up the project and considered the ethical issues. See the section on this website about working ethically, including the downloadable Guide to the ethics of working with flood-affected people.

Data collection methods Different research methods are suitable for different groups. The Lancaster research team has used a range of methods when working with children and adults and this has generated a variety of data.

Working with children

The Lancaster team has drawn on a range of qualitative approaches designed to support children in voicing their experiences and thoughts in a safe environment. These include:

Drama/team-building

Workshops with children have started and ended with drama and team-building activities. These help to build trust among the group, to ‘warm up’ skills such as observation and to promote a fun, creative but also reflective atmosphere with scope for analysis and evaluation.

Warm up activity

Data produced:

- Photographs of children taking part in drama and evaluation activities

- Audio-recordings of children talking during evaluation activities (and written transcripts of these)

Walk & talk and photo talk

Walk & talk activity

Following the warm-up activities, the Children, Young People and Flooding project workshops began with walk & talk: walking with the children in the local flood-affected area and recording the conversations along the way. The children took photos of things or places that reminded them of the flood, such as skips, flood-damaged buildings and riversides. There were also scenes of recovery like houses being rebuilt and renovated and on-going essential drainage works. Back in the workshop, children used the photos they took on the walk to share stories in the group during a photo talk session, which was also recorded.

Photo talk activity

Data produced:

- Audio recordings of children talking during the walks (and written transcripts of these)

- Photographs children took during the walks

- Audio recordings of children talking about their photographs (and written transcripts of these)

Sandplay and 3D modelling

Knowing how hard it is for people who have been flooded to convey what they have gone through, the Children, Young People and Flooding project used 3D modelling to invite the children to share their experiences. A great way to start is with sand, a simple and playful means to connect with expressing ideas and memories using tactile materials. This then led to thinking about how to express parts of the story in more complex 3D. The children used a range of materials (such as clay, sticks and moss to wool, textiles and buttons) to show what happened and how the flood still affected them. Once completed, the children shared what they had made with others in their group, naming the different parts of the models and talking about what each feature meant.

Group modelling activity

Data produced:

- Photographs of children taking part in sandplay and modelling activities

- Photographs of individual and group models created by the children

- Audio recordings of children talking about their models and the sandplay/model-making process (and written transcripts of these)

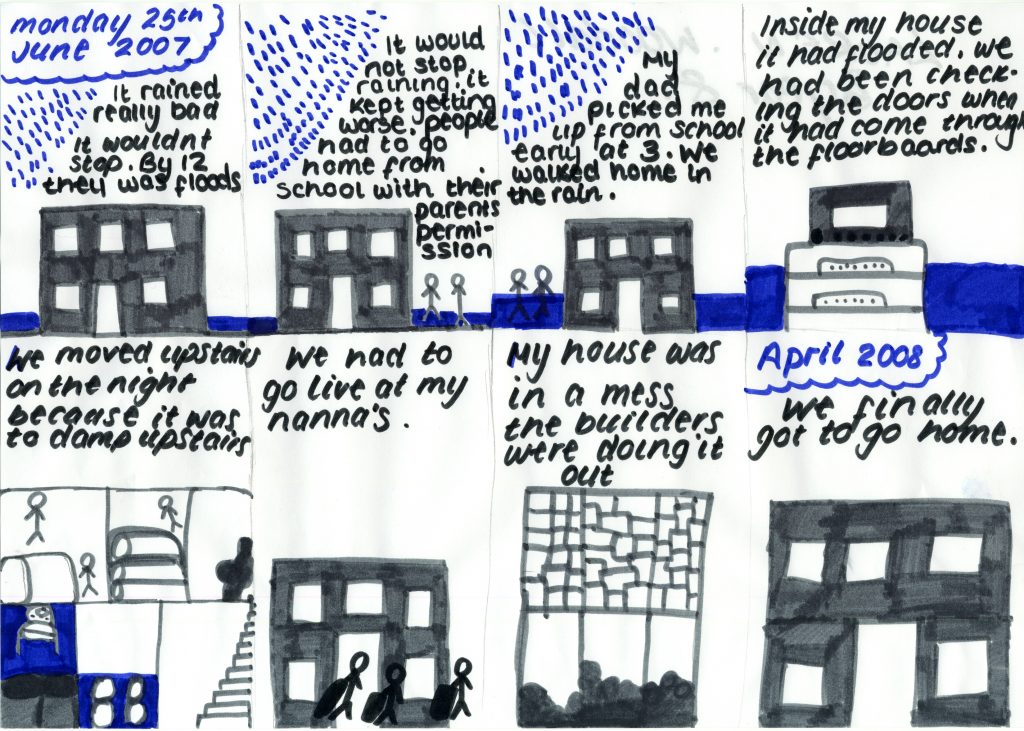

Storyboards

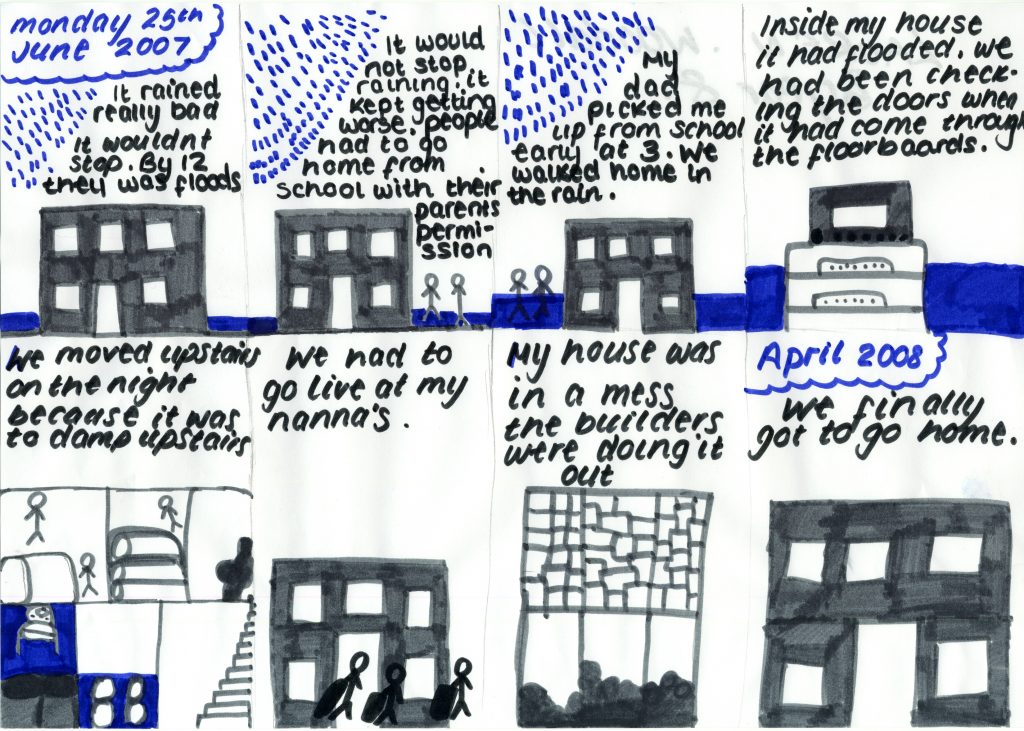

The Hull Children’s Flood Project adopted a storyboard methodology, where children drew pictures or used creative writing to tell their stories. Following group warm-up activities, the research team showed a presentation called ‘And Then What…?’, built around a series of images from the Hull 2007 floods, which was designed to get the children thinking about their own memories and experiences. The children were then given drawing materials and blank pieces of A3 paper and encouraged to choose their own ways of representing their ‘flood journey’, starting on the day of the flood and going up to the day of the research workshop. The research team followed up with individual interviews about the storyboards.

Data produced:

- Children’s storyboard drawings

- Audio recordings of individual discussion about the storyboards (and written transcripts of these)

Storyboard about displacement created during the Hull Children’s Flood Project.

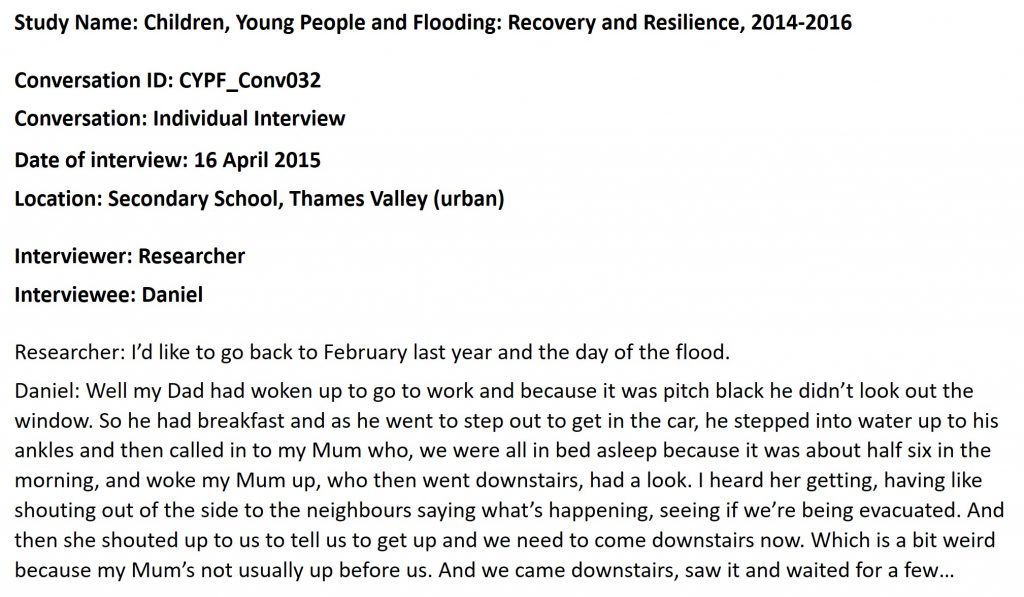

Individual Interviews

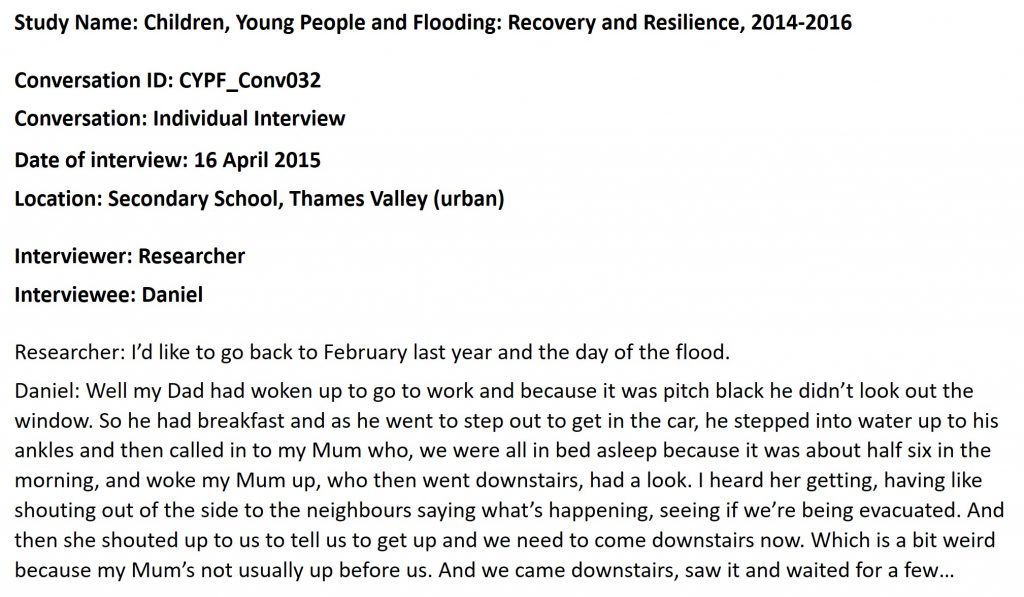

The team involved in the Hull Children’s Flood Project used the children’s storyboards to generate questions to use in short semi-structured interviews. Each child was encouraged to talk in more depth about their storyboards with a researcher in a one-on-one discussion. Some young people from the Children, Young People and Flooding project also requested individual interview as a follow-up to the group workshops.

Data produced:

- Audio recordings of individual interviews with children (and written transcripts of these)

Section from transcript

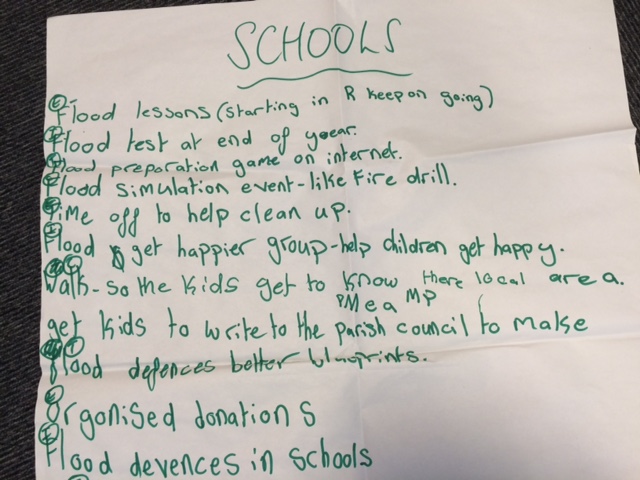

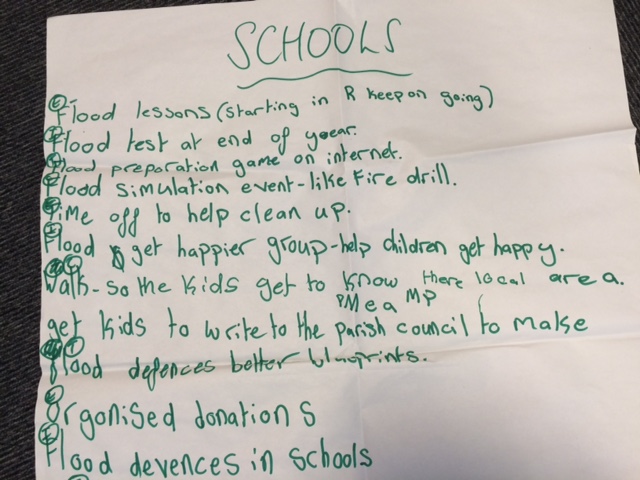

Group Discussion

During the Children, Young People and Flooding project, the research team took some of the data (interview transcripts and photographs) back to a workshop with the children and used this as a stimulus for discussion. The children were invited to identify key themes and concerns and then work together to identify decision makers involved in flood risk management and the key messages they wanted to convey to them. Ideas from these group discussions were pooled together (as below) and later written up as ‘flood manifestos’.

The children’s notes from their group discussion

Data produced:

- Audio recordings of children’s group discussion (and written transcripts of these)

- Written notes produced by children during group discussion

Stakeholder engagement events

At the end of the Children, Young People and Flooding project, the children worked together to create performance-based pieces that were presented to audiences of stakeholders affected by flooding and involved in flood risk management. These performances incorporated quotations and photographs from the project, brought to life through drama sketches, sound sequences and children reading aloud. At the end the audience was handed the children’s ‘flood manifestos’ and asked to write individual pledges of action in response.

Stakeholder event

Data produced:

- Stakeholder event performance scripts

- Video of performances by children

- Written pledges generated at stakeholder engagement events

Working with adults

The Lancaster research team has used a range of in-depth qualitative methods to better understand adults’ experiences of flooding and the drawn out process of recovery. These include:

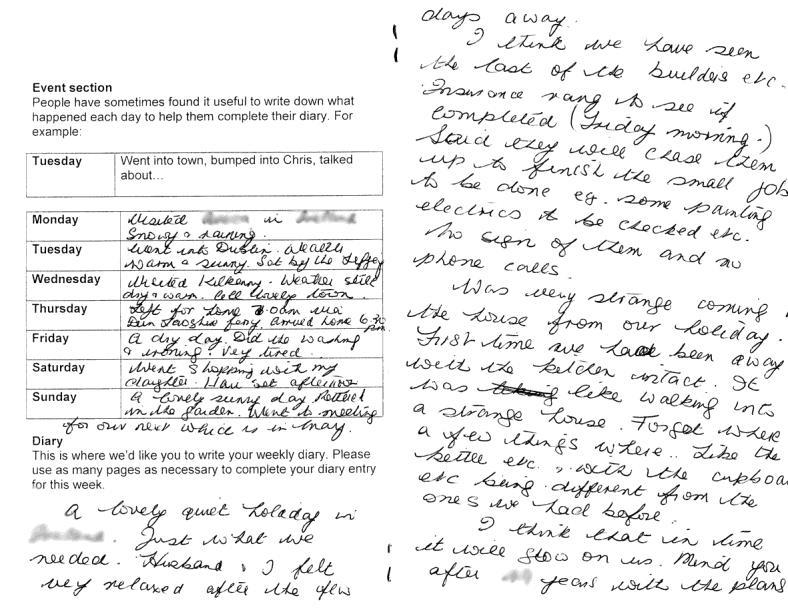

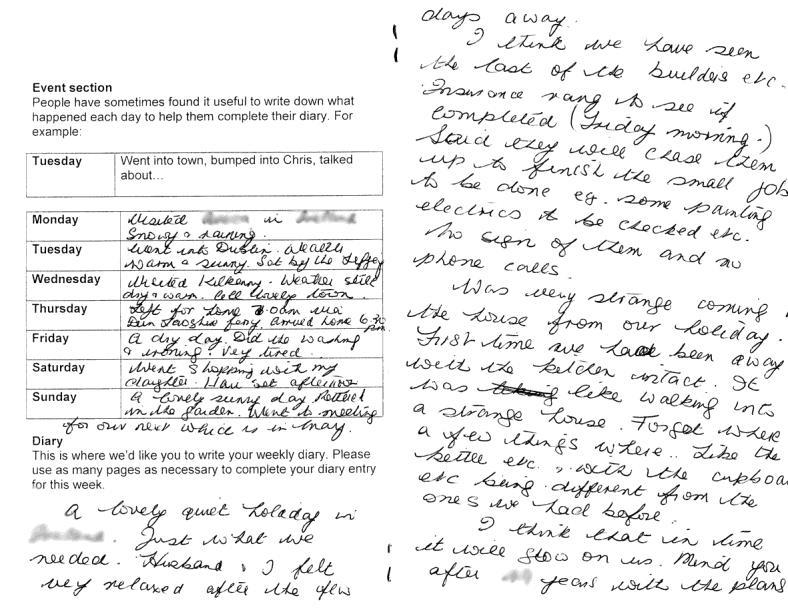

Written diaries

During the Hull Floods Project, adults were invited to keep weekly diaries over an 18 month period. This approach gave participants the freedom to choose what to write about in their own words while providing a real-time record of events and experiences, thereby tracking their own recovery process, week by week. The diary booklet began with a few ‘warm up’ exercises where participants were asked weekly to rate their health, quality of life and relationships with family and friends, using a simple scale ranging from ‘very poor’ to ‘very good’. There was also a section where they could enter details of what they had done on particular days that week. This got the participants used to writing in readiness for the main free-text section where they wrote whatever they liked about their lives that week.

Data produced:

- Written diaries of adults recovering from flooding

Group discussions

The adults involved in the Hull Floods Project requested to meet quarterly as a group. These group discussions followed a semi-structured format: the researchers introduced key issues identified from initial readings of the participants’ diary material but, for the most part, the team simply let the conversation flow and participants bring up issues most relevant for them. The initial aim of the discussions was to encourage group reflection on the challenges participants were facing and suggestions for the future, but it was recognised that these discussions came to play a ‘therapeutic’ role, while also supporting the emergence of participants’ expertise as they grew more confident about sharing their experiences and opinions. This emerging expertise meant that the groups evolved to take on a more participatory, consultative role in the project.

Data produced:

- Audio recordings of adults’ group discussions (and written transcripts of these)

Individual interviews

The Lancaster research team has conducted one-on-one interviews with adults flooded at home and at work, as well as with those involved in flood response and recovery.

Data produced:

- Audio recordings of individual interviews with adults (and written transcripts of these)

Stakeholder engagement events

The Hull Floods Project culminated in a day-long stakeholder engagement event, bringing together the project participants with key agencies such as water companies, government departments, local authorities and the insurance industry. The workshop included discussions about the recovery process following a flood and how to build resilience to future flooding.

Data produced:

- Written notes from workshop discussions

- Audio recordings of group discussion (and written transcripts of these)

- Photographs and video of the event

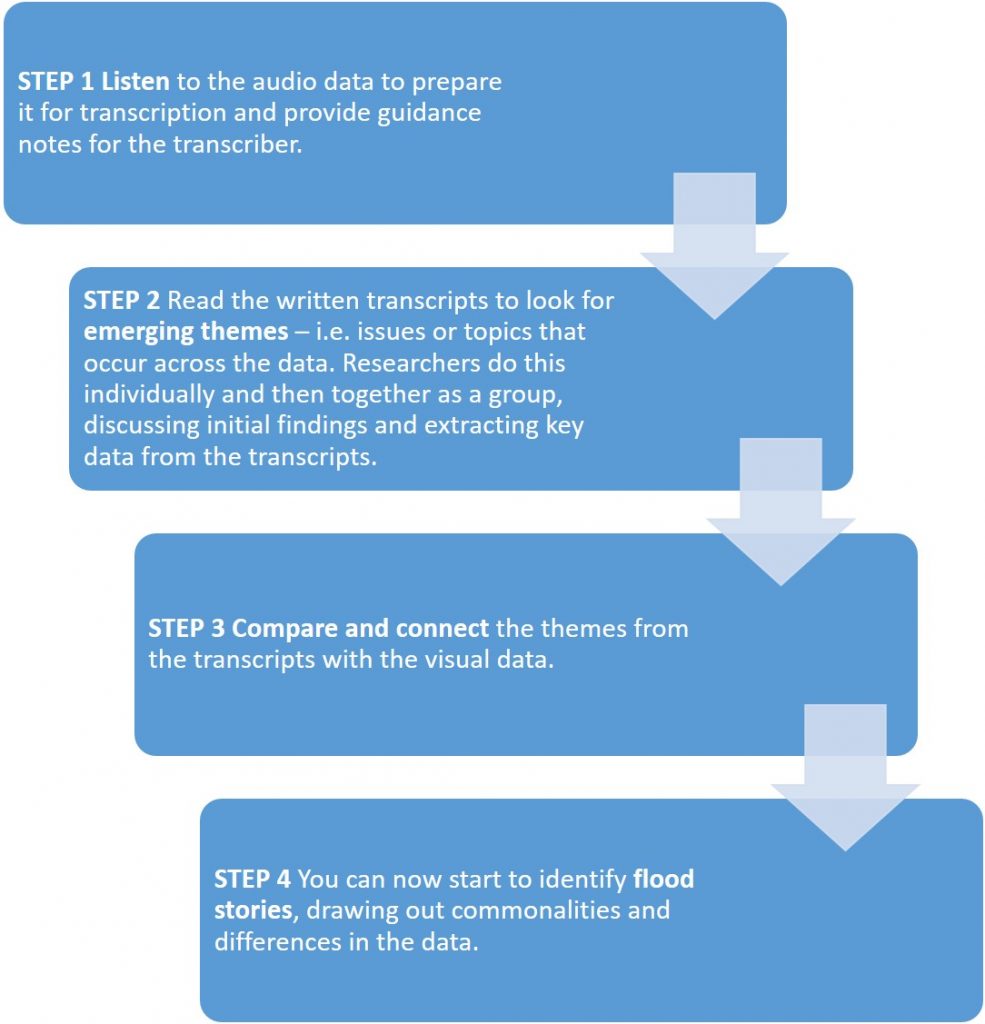

After collecting data Data can be used simply as evidence of your community activity/engagement, but it can also be analysed to help you develop further flood resilience work or inform policymaking.

Remember to store your data carefully. See the section on this website about working ethically, including the downloadable guide, Working with flood-affected people.

Please reference as: Flooding – a social impact archive, Lancaster University

This ‘How To’ Guide provides an introduction to the main issues to be aware of when working with flood-affected people, families and communities.

This ‘How To’ Guide provides an introduction to the main issues to be aware of when working with flood-affected people, families and communities.