Here you will explore:

- what is meant by ‘working ethically’ with flood-affected people

- the steps involved in ensuring you work ethically

What does it mean to ‘work ethically?’

It is vital to work sensitively with flood-affected people, considering carefully both when and how any research is conducted. Timing is critical: it is important not to try and conduct the work too soon after the flood event, as people may still be dealing with the aftermath and recovery; too long after and you may find that people simply want to move on and don’t wish to revisit the event.

Working ethically also means working in a participatory and inclusive way. This is partly to ensure that all voices join the conversation, particularly those belonging to groups regarded as more vulnerable such as children, older people and people with disabilities. It is also about creating a safe space in which people feel able to talk and share experiences, choosing appropriate data collection methods and ensuring that people are able to give informed consent to take part in the work, including the option to withdraw if they wish.

During Lancaster University’s research projects in flood-affected communities, the team has worked in as participatory a way as possible. This stems from a theory of knowledge which regards flood-affected people as ‘experts’ with a great deal of knowledge and insight to share. Starting from this perspective meant that the team sought to learn from the participants’ experience and expertise in flooding and aimed to generate data ‘with’ the participants, rather than ‘from’ them.

Steps to working ethically

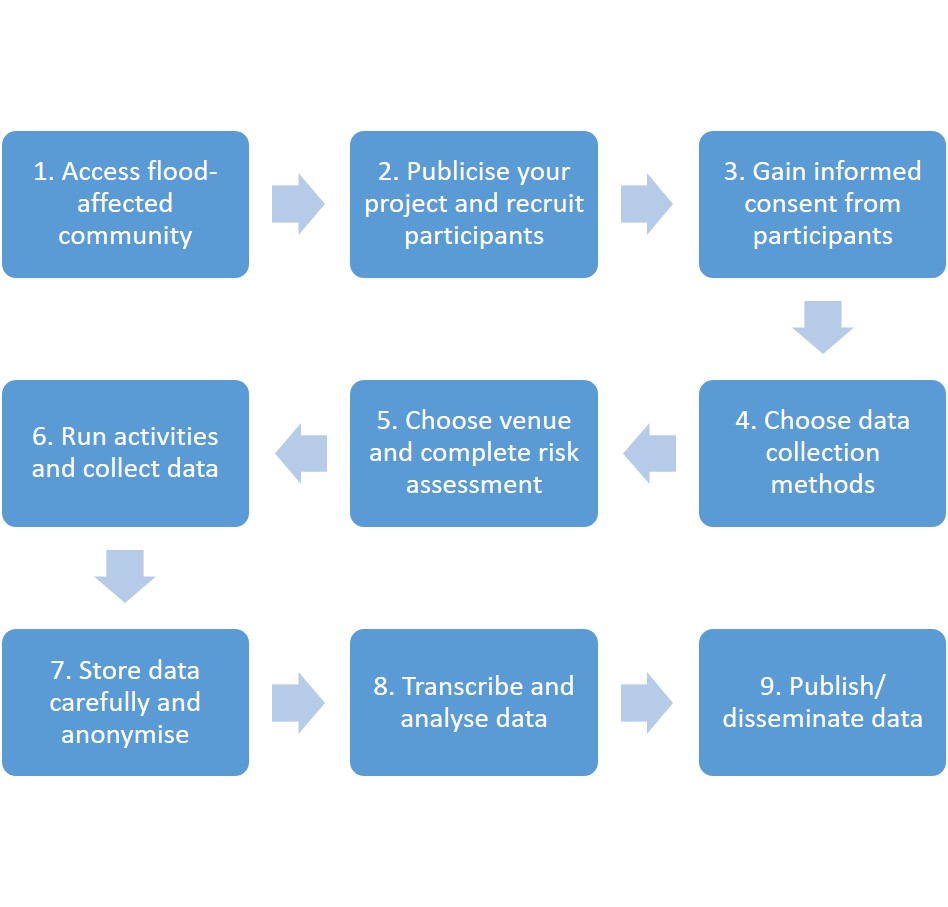

The flowchart above outlines the steps to ensuring you work ethically and sensitively with flood-affected people – from initially gaining access to the community to publishing the data gathered with them.

Downloadable resources

The steps in the flowchart are explained in more detail in a downloadable guide, Working with flood-affected people. You can also download example participant consent forms that can be adapted. There are two versions: a standard consent form and an accessible consent form, which uses pictures and less text.

Please reference as: Flooding – a social impact archive, Lancaster University