Adelene Buckland is Senior Lecturer in Nineteenth-Century Literature at King’s College London, and a member of the Davy Notebooks Project Advisory Board

I first encountered Humphry Davy while reading Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830-33), one of the most important books in the history of a science which in 1830 was still new and – to many – shocking. Early in that book, Lyell attacks the idea of progress in the history of the earth – the idea that life has progressed from relatively simple to more complex forms through time. He does so by quoting at length from the ‘Unknown’, a quasi-mystical philosopher who expounds upon the theory of progress in Davy’s Consolations in Travel (1830). As the Unknown puts it, ‘there seems, as it were, a gradual approach to the present system of things, and a succession of destructions and creations preparatory to the existence of man’ (p. 149).

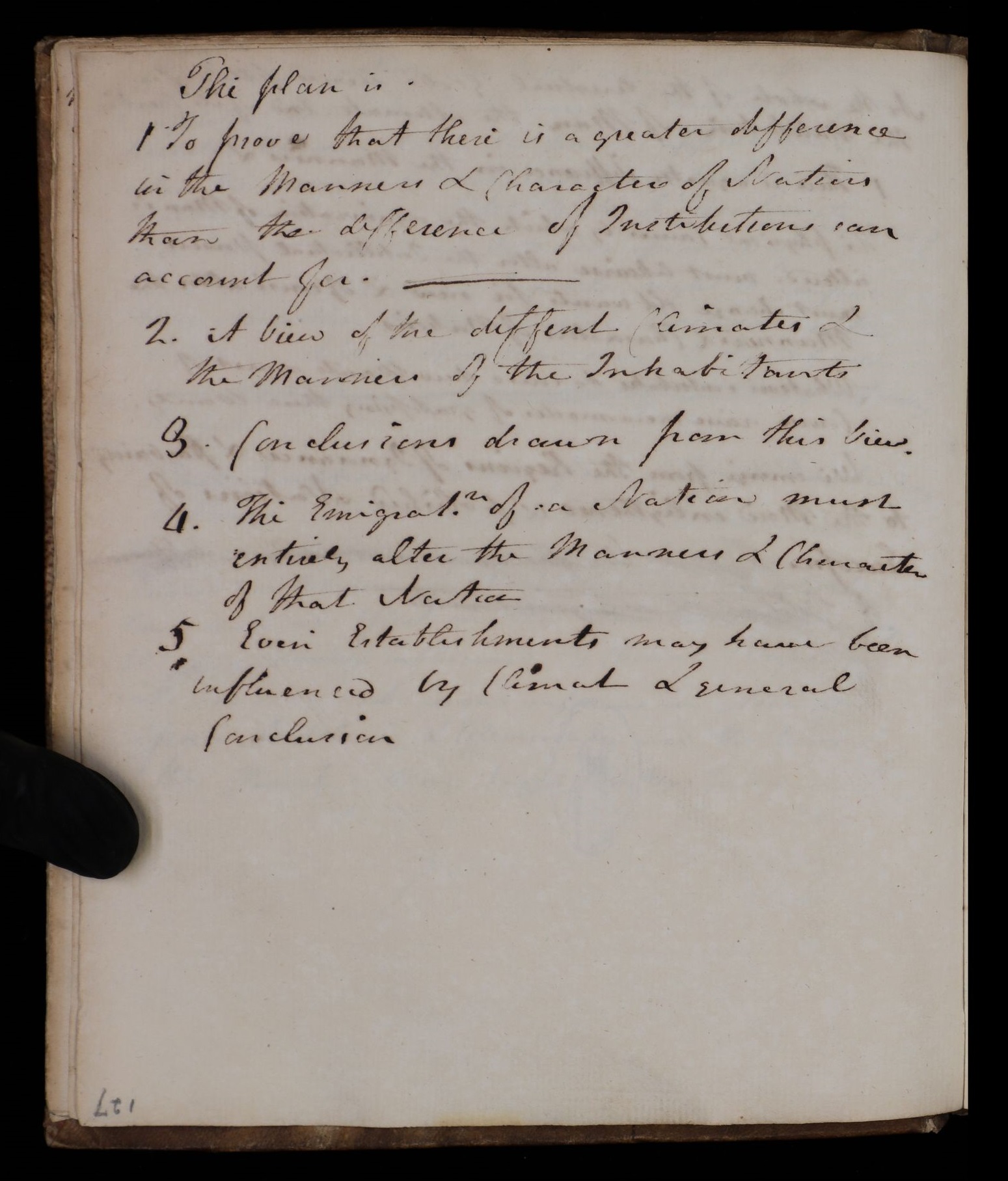

Detail from title-page of Davy, Consolations (3rd edn, 1831)

Davy’s account of the idea of geological progress is succinct and beautifully written, and it summarises an idea that was quite widely accepted among geologists in this period. But the text was a strange one for Lyell to engage with. Consolations in Travel isn’t a geological book in any straightforward way, and it is not typical of Davy’s work. Davy was not primarily known as a geologist. In fact, Davy wrote Consolations when he knew he was dying, and the book is perhaps best read as a last-ditch attempt to synthesise a vast body of knowledge from across a range of disciplines – from art, religion, architecture, and history to geology, biology, and astronomy. It is modelled on a dizzying array of other texts, from the Roman philosopher Boethius’s sixth-century Consolation of Philosophy to more radical and contemporary French philosophical texts which argued for the death of kings and gods. And it patches together a multitude of other genres and literary forms: it is part Byronic travelogue, part pilgrimage, part Socratic dialogue (in which a series of hypotheses are debated and eliminated by gentlemen who work out their contradictions through conversation), part medieval dream vision, with debts to the ‘philosophical romance’ (a form of heavily footnoted scientific poetry) and to The Arabian Nights. Lyell was seeking to give the new science of geology a rigorous methodological underpinning. There were plenty of more established geological writings with which he could have engaged. Why did he choose to quote at length from this strange, often supernatural text?

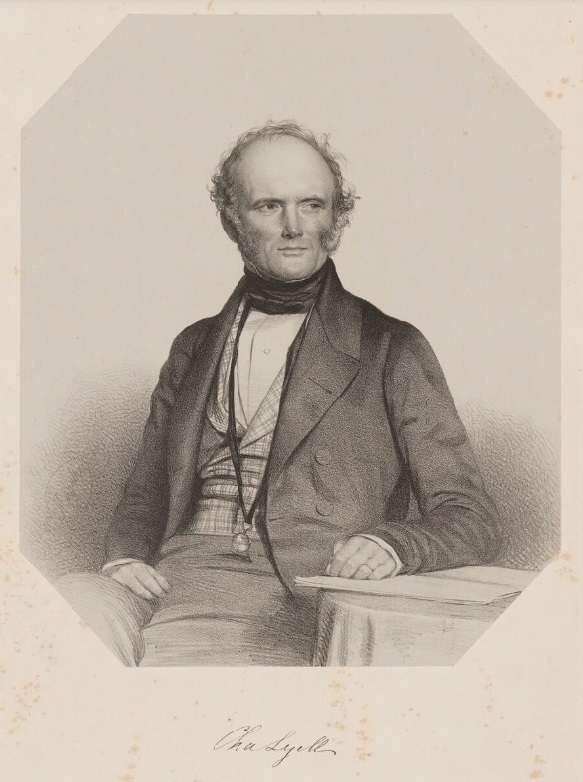

Lithograph of Lyell by Thomas Herbert Maguire, 1849 (National Portrait Gallery, NPG D38030. Reproduced under the terms of CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The answer, I think, is (at least) twofold. First, and most obviously, Lyell was speaking to the educated public in his work – not just a handful of geologists. Davy’s fame helped Lyell to reach a wider audience. But the second reason is the most interesting, and my students helped me see it. Shortly after reading Consolations, I decided to teach it in the first week of an undergraduate course on nineteenth-century literature and science. I thought it might be too complex and too weird to teach in a single lecture and seminar. But they loved it. And what they loved – and what I love, and what I think was so important to Lyell – was that Davy is constantly interested in the relationship between scientific knowledge and the problems of human consciousness, imagination, and perception. As he put it, ‘human intellectual powers are so feeble that they can with difficulty embrace a single series of phenomena, and they consequently must fail when extended to the whole of nature’ (Consolations, p. 131). ‘The Unknown’ who tells the story of the history of the earth in Consolations is an echo of another figure, the ‘Genius’, who appears in Consolations in a vision and guides Davy’s protagonist through the solar system, revealing celestial beings each of whom has more refined sensory knowledge of the universe than the last. Human beings have sight, Davy argues, but vision is another matter. The imagination, used rightly, was a tool for understanding the deep secrets of the universe that the frail evidence of the senses (not to mention the rocks and fossils) could not be relied upon to detect. After my students helped me pick up on this idea, I elaborated on it in two essays partly on Davy – for The Routledge Research Companion to Nineteenth-Century Literature and Science, and another essay in Time Travelers: Victorian Perspectives on the Past. There is still so much to be explored about Davy’s ideas about imagination, vision, and genius in scientific work.

In these ways, I think, Davy’s greatest contribution to geology was not that he named or classified a new species, or a new series of strata, or a new geological epoch. It was that he understood the challenge this new science represented to the imagination, and to quotidian notions of the human in relation to the grandeur of the earth and the universe. He understood geology as a set of imaginative problems. Lyell did, too, as he compelled his readers to reimagine earth history taking place over millions and millions of years. Though Lyell and Davy came to different conclusions, they were both preoccupied underneath it all with a similar set of questions: what did it mean to be human in a world so much older than human beings? What did it mean to be human when great ancient lizards (we now call them dinosaurs) had once walked the earth? What did it mean to be human when it was so impossible to reconstruct this history with any certainty, when so much of the evidence was locked deep underground in areas of the earth to which humans had no access? To what extent were these inaccessible layers of the earth to be understood as metaphors for layers of knowledge, or of consciousness, inaccessible to fragile human minds? These ideas – that human beings just don’t know themselves or the world they live in, and perhaps can never know – would be influential in so many subsequent fields of study. Freud’s sense of the mind as mineable layers of strata, hidden from itself, is just one.

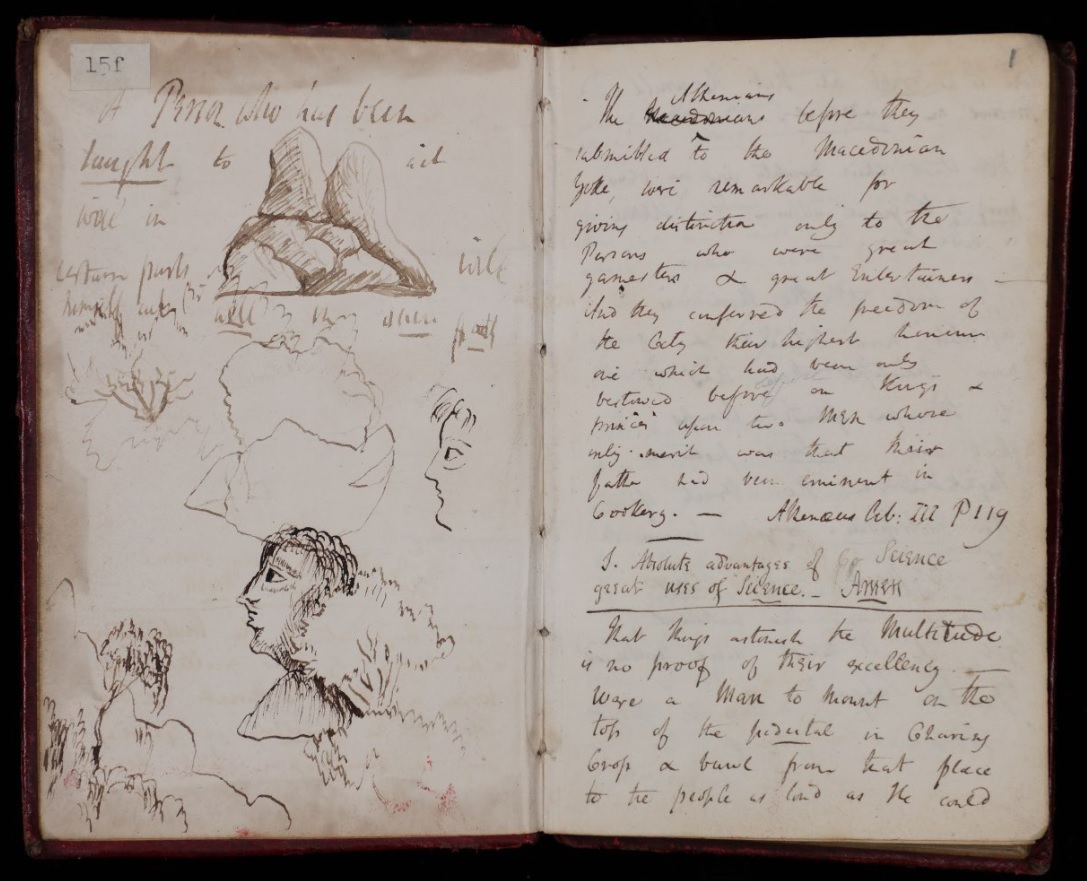

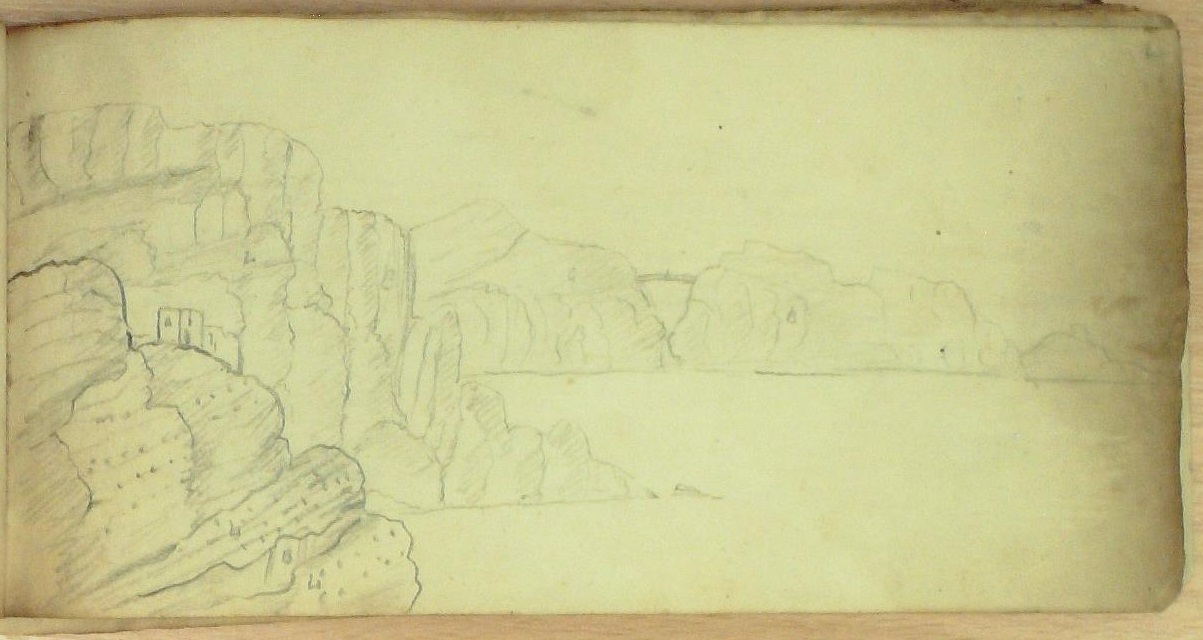

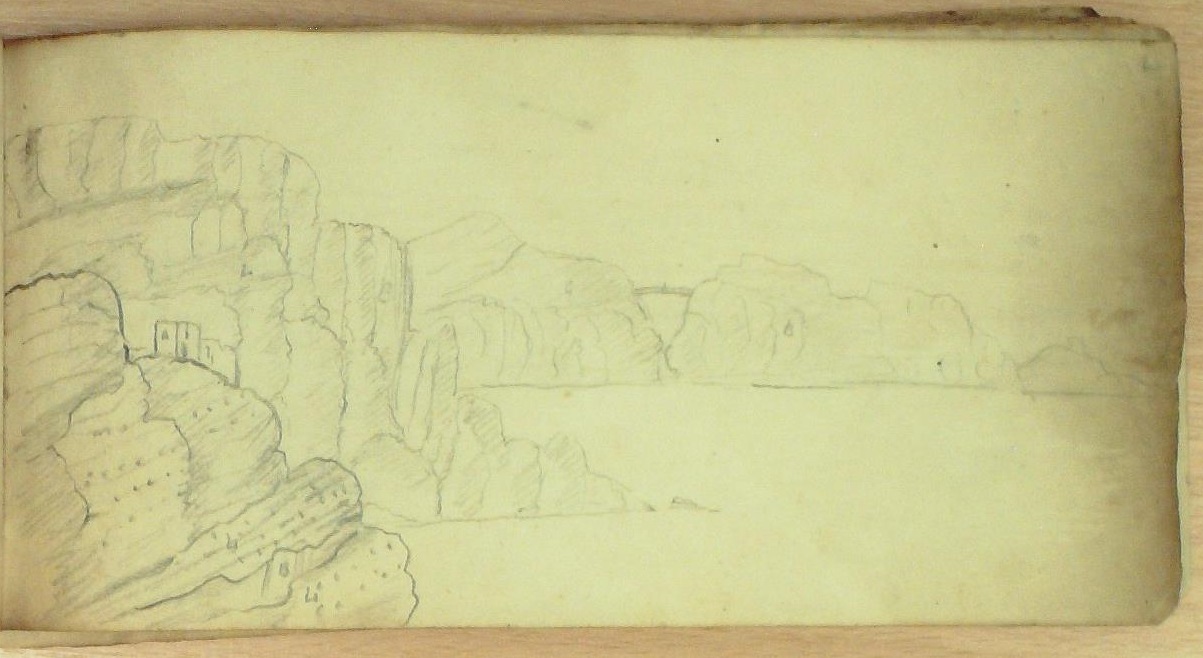

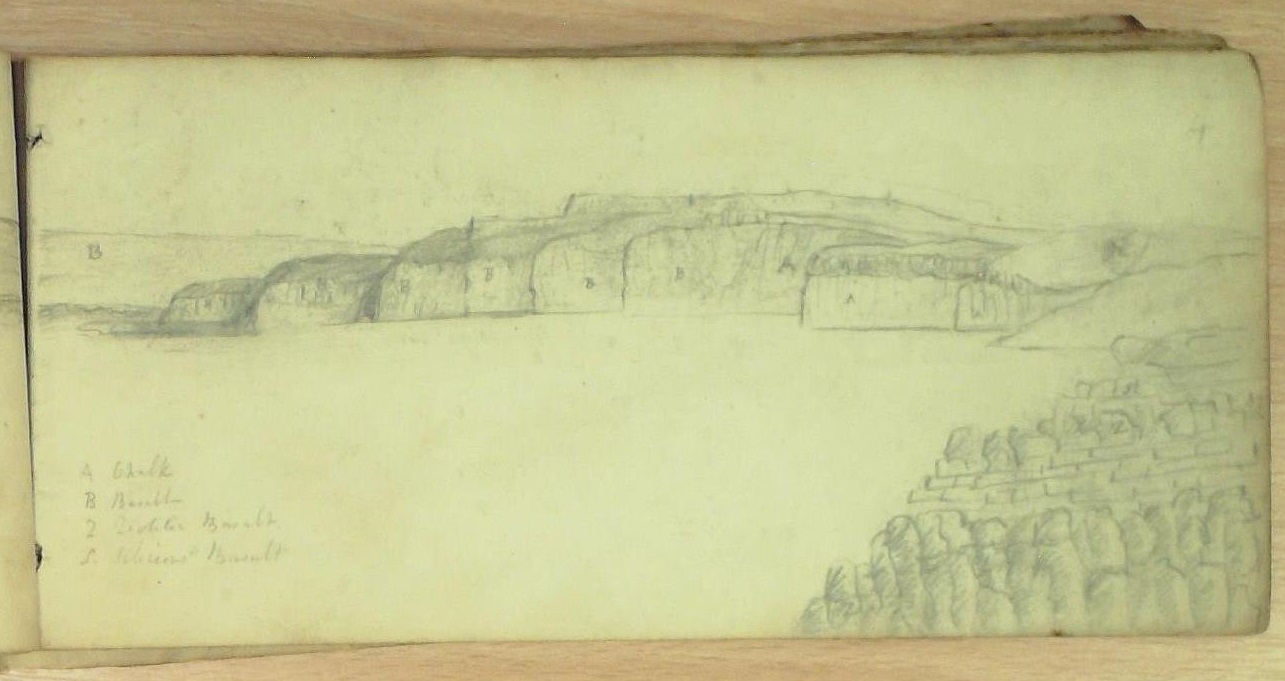

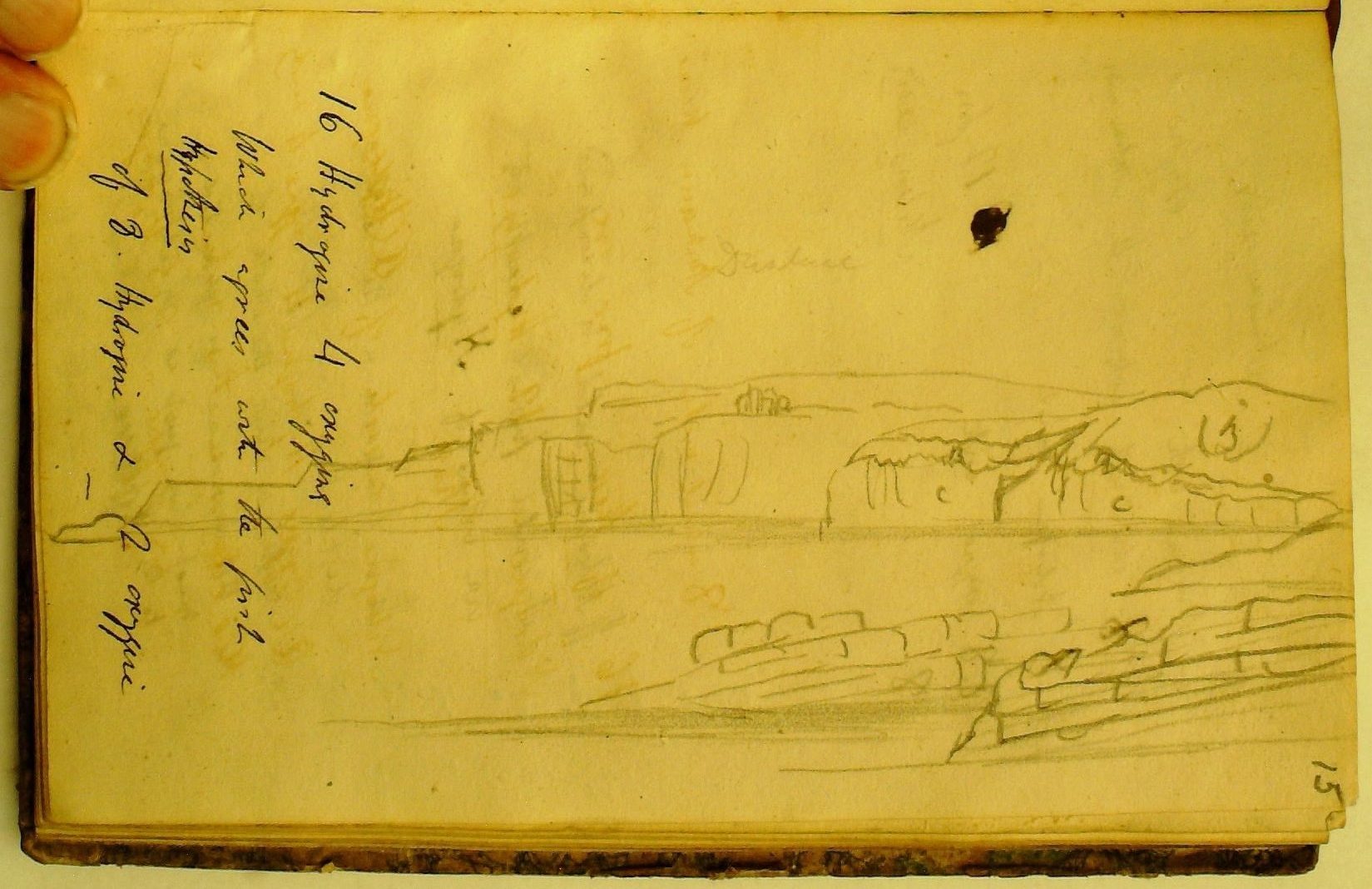

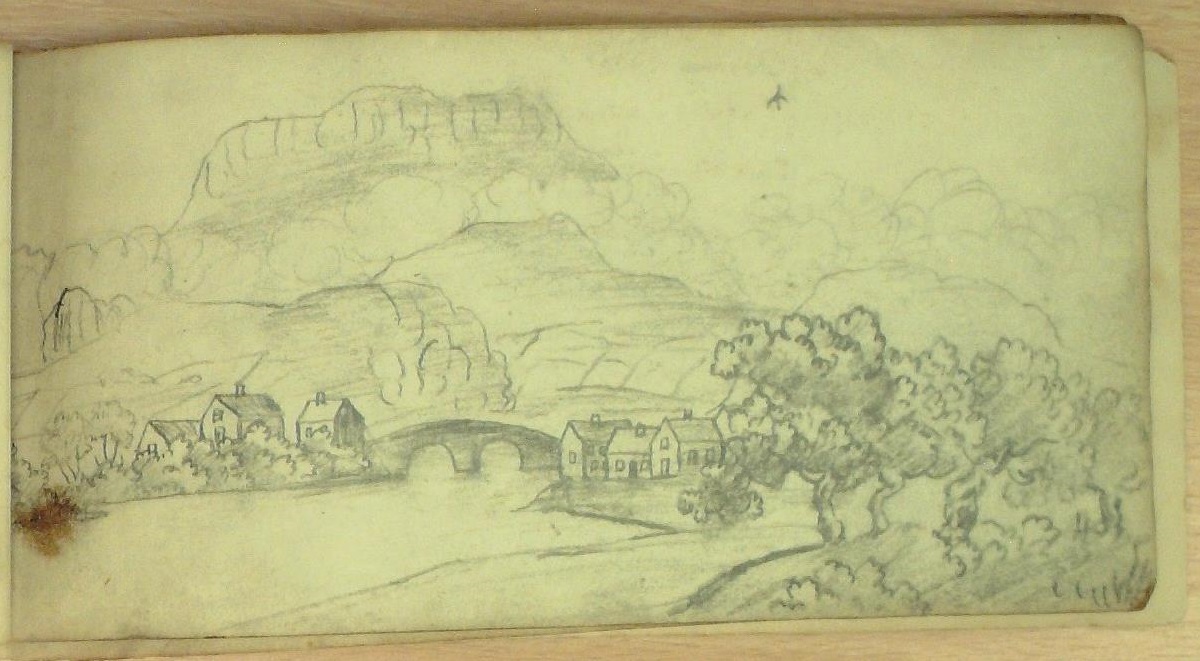

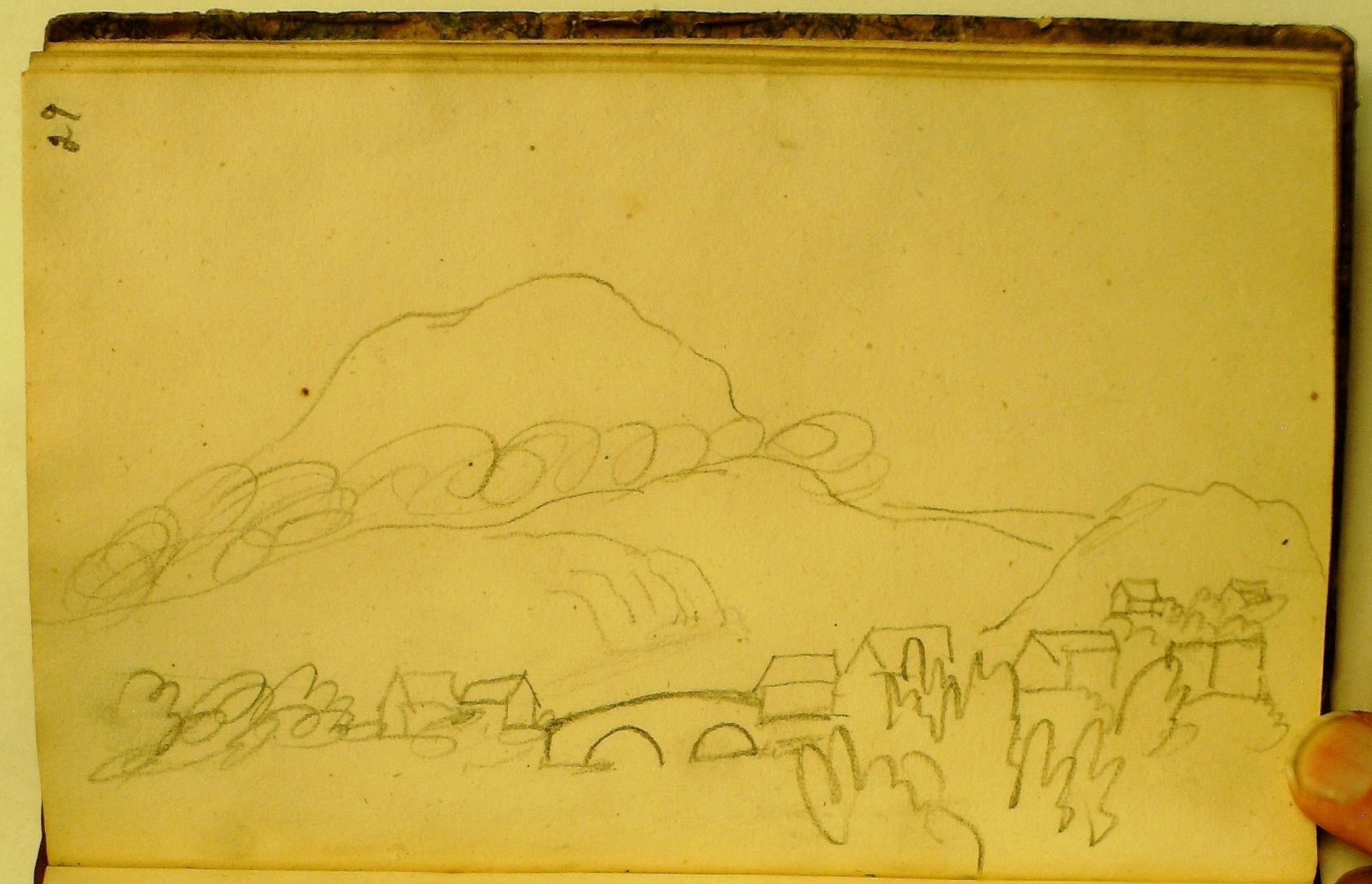

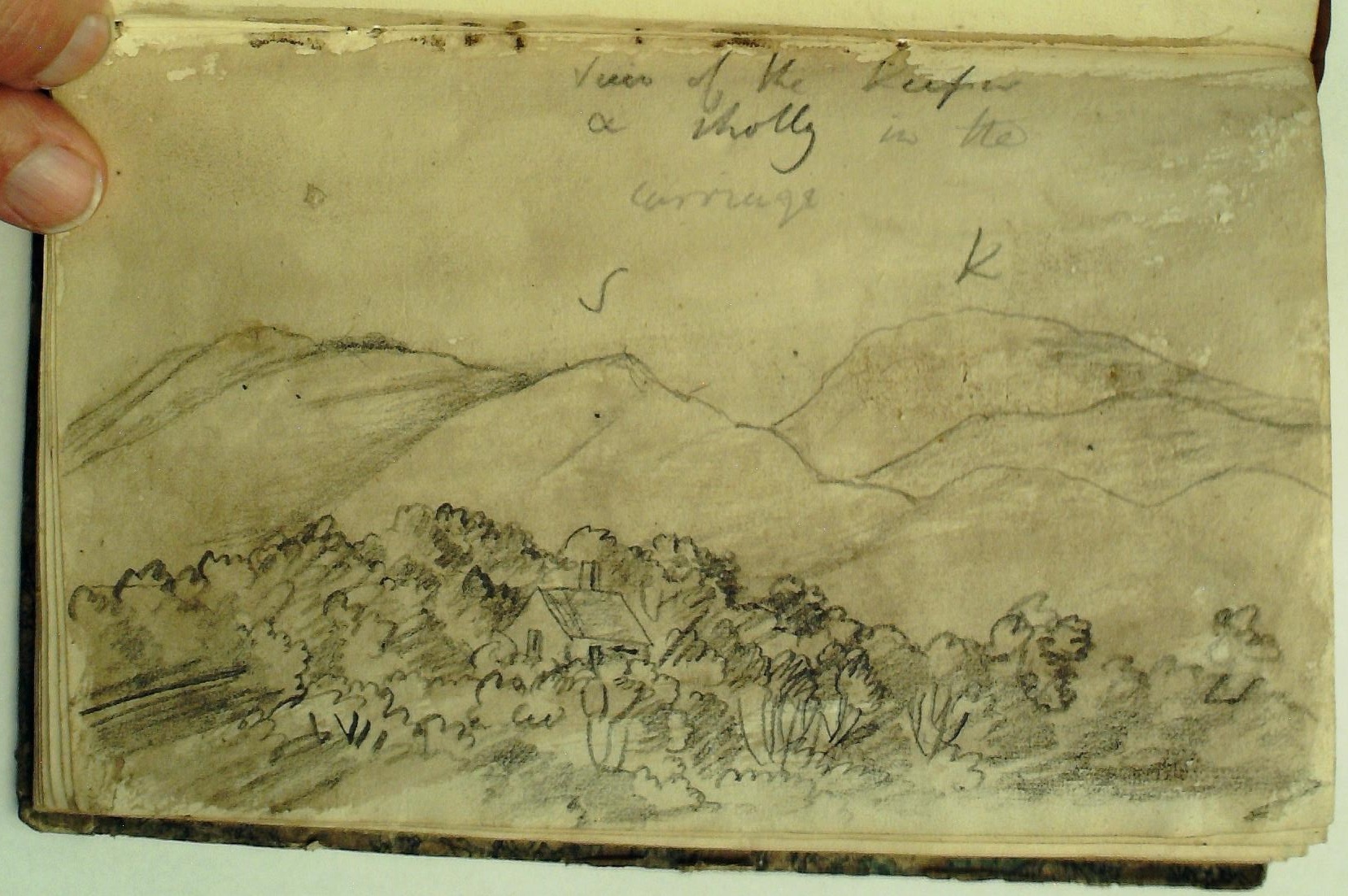

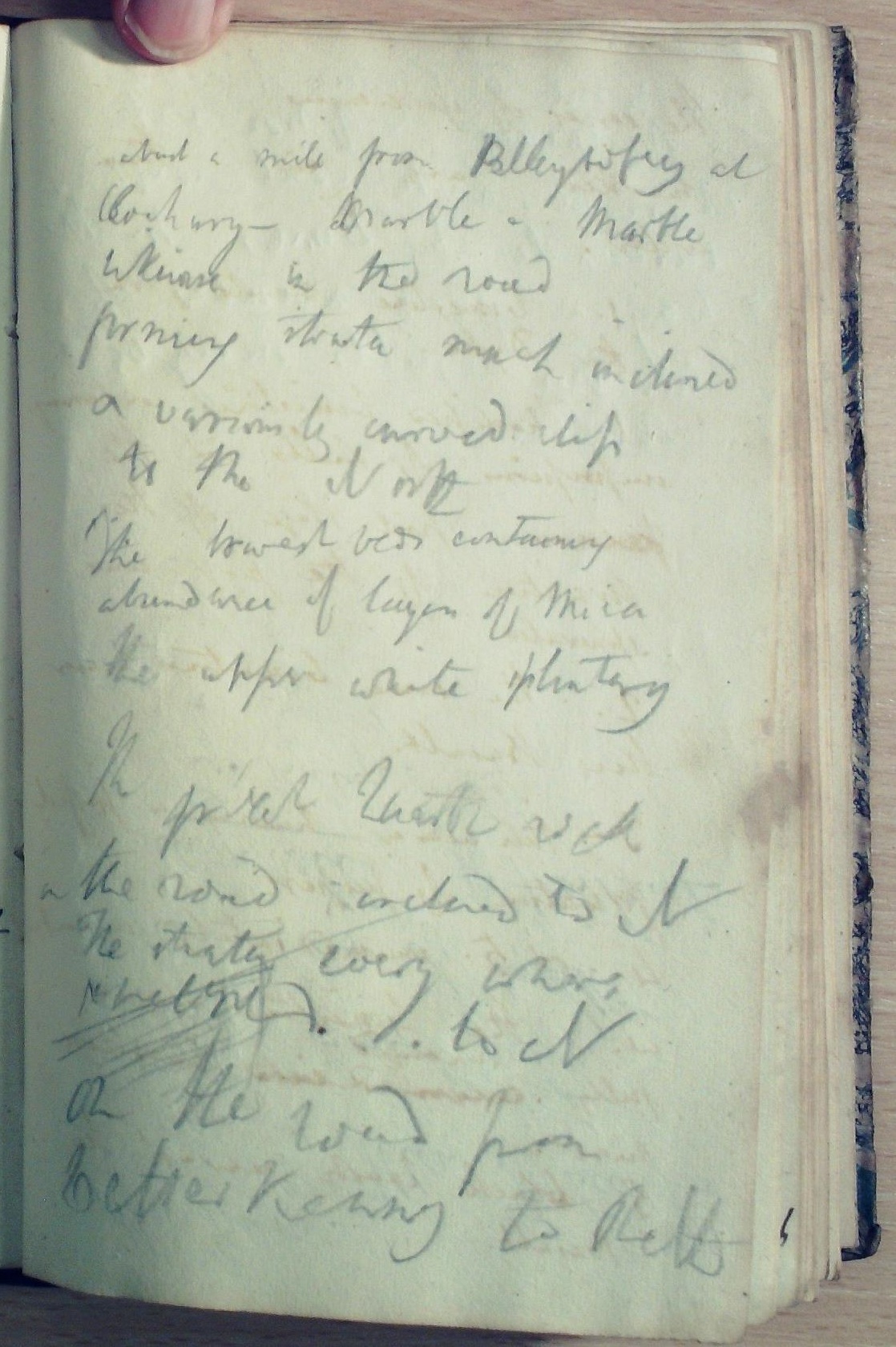

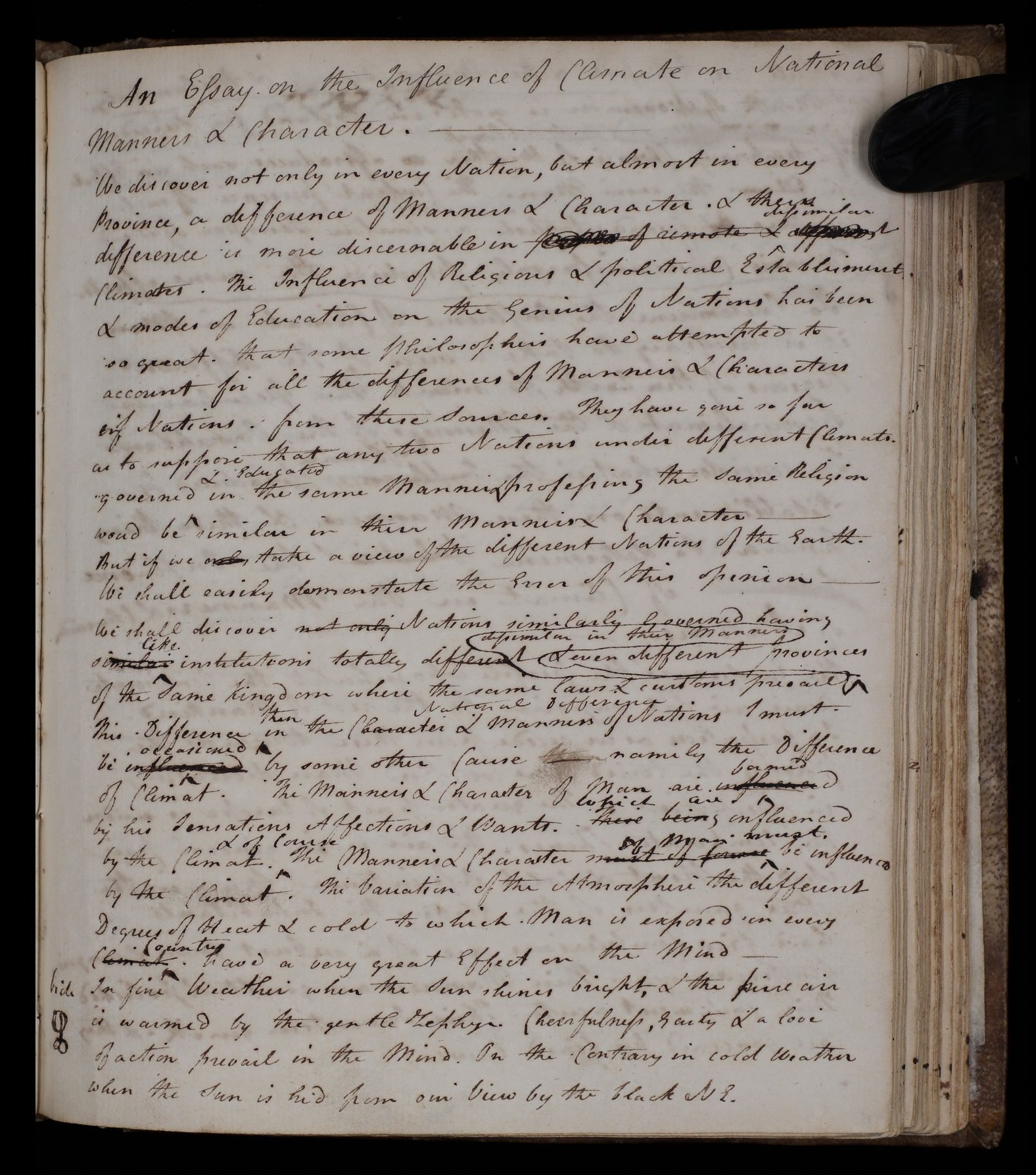

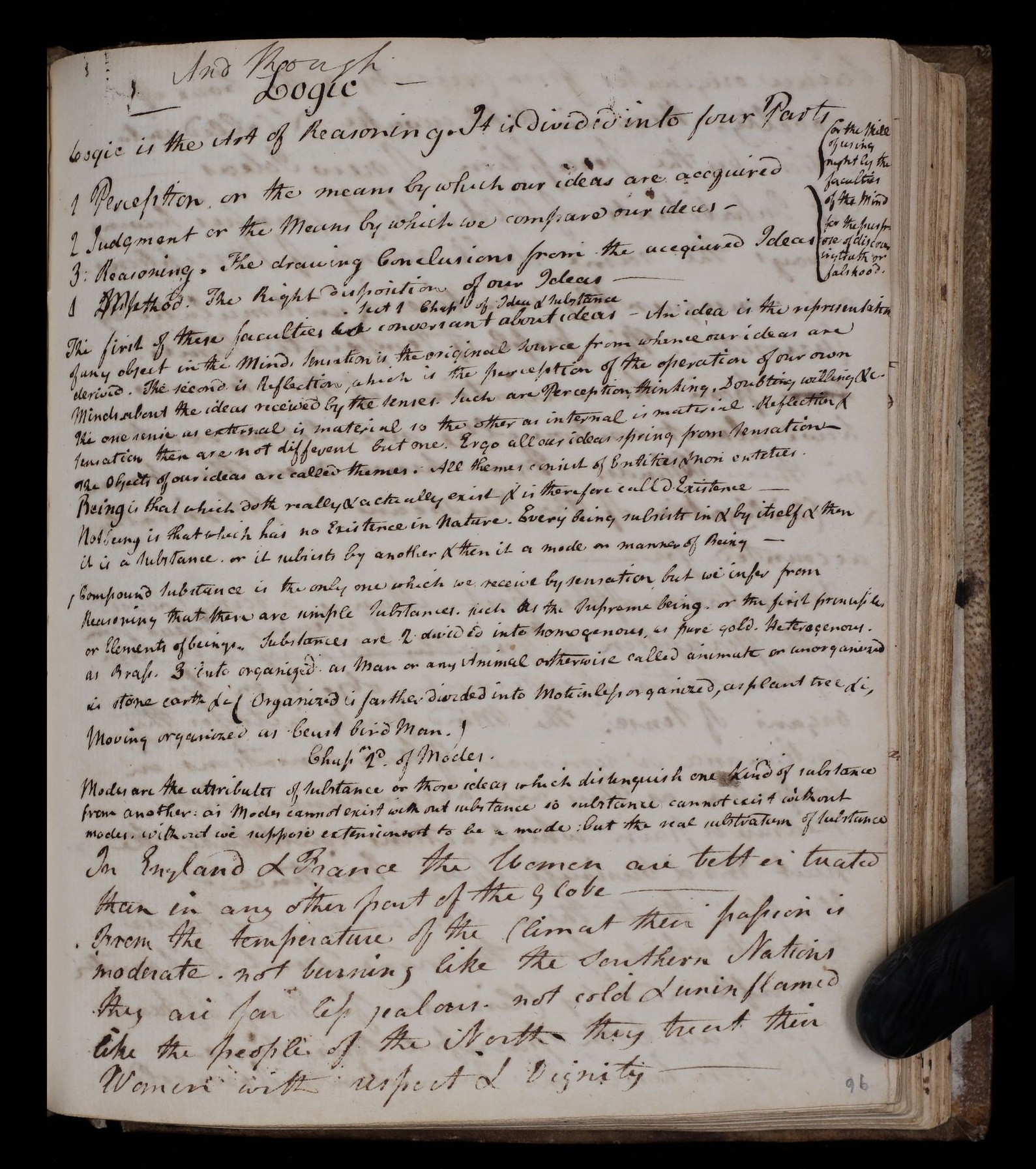

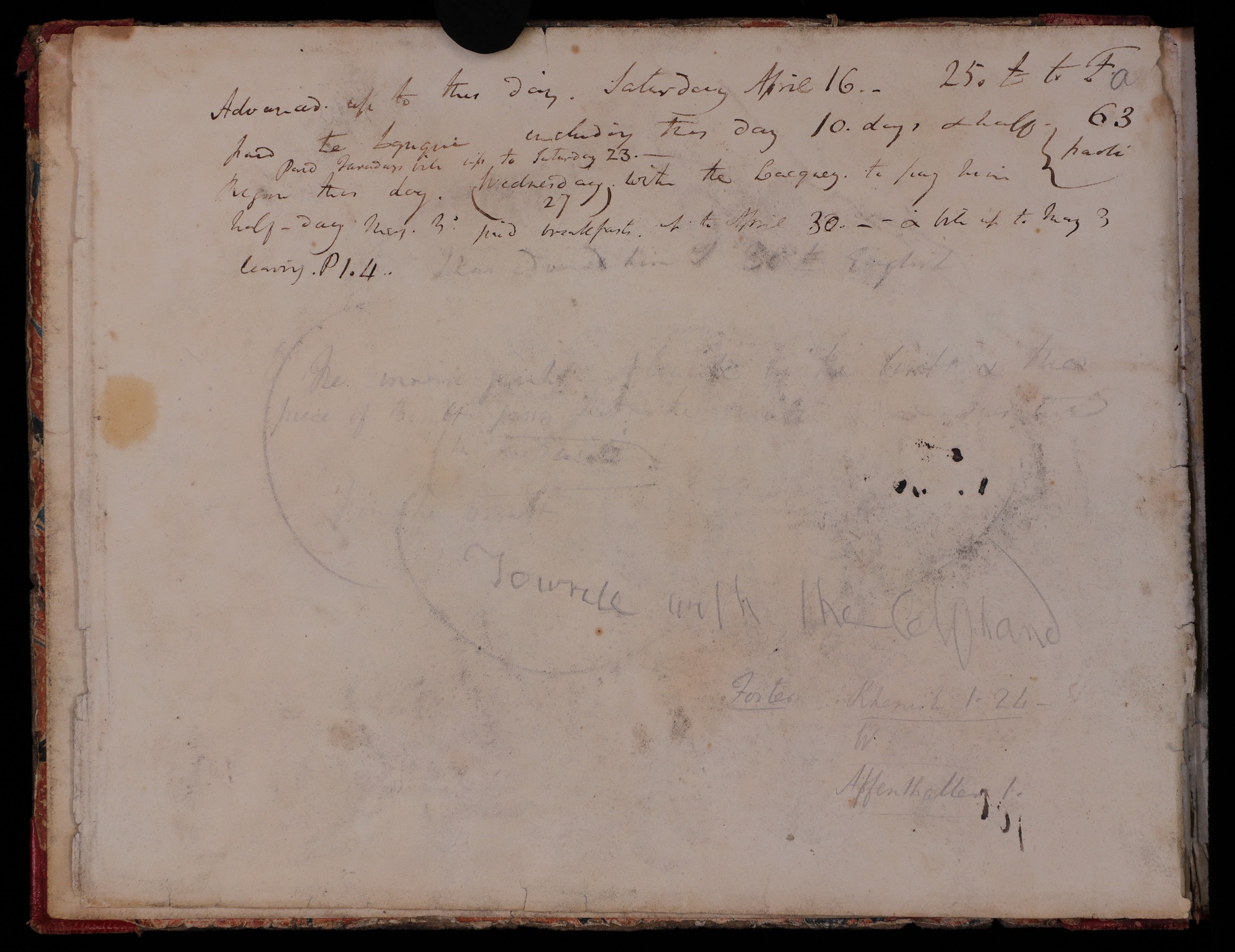

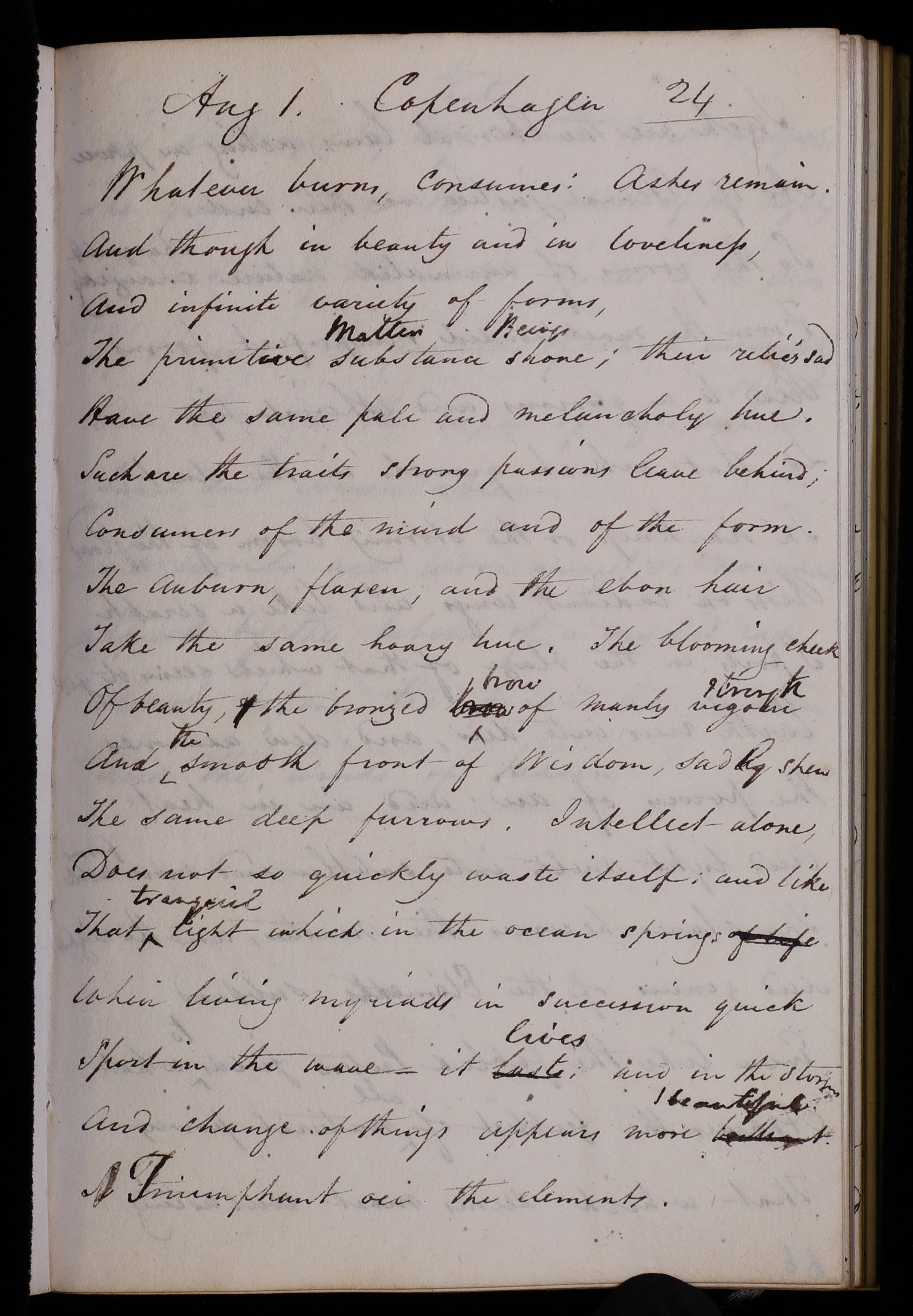

RI MS HD/15/F, front endpaper and p. 1 (click to enlarge)

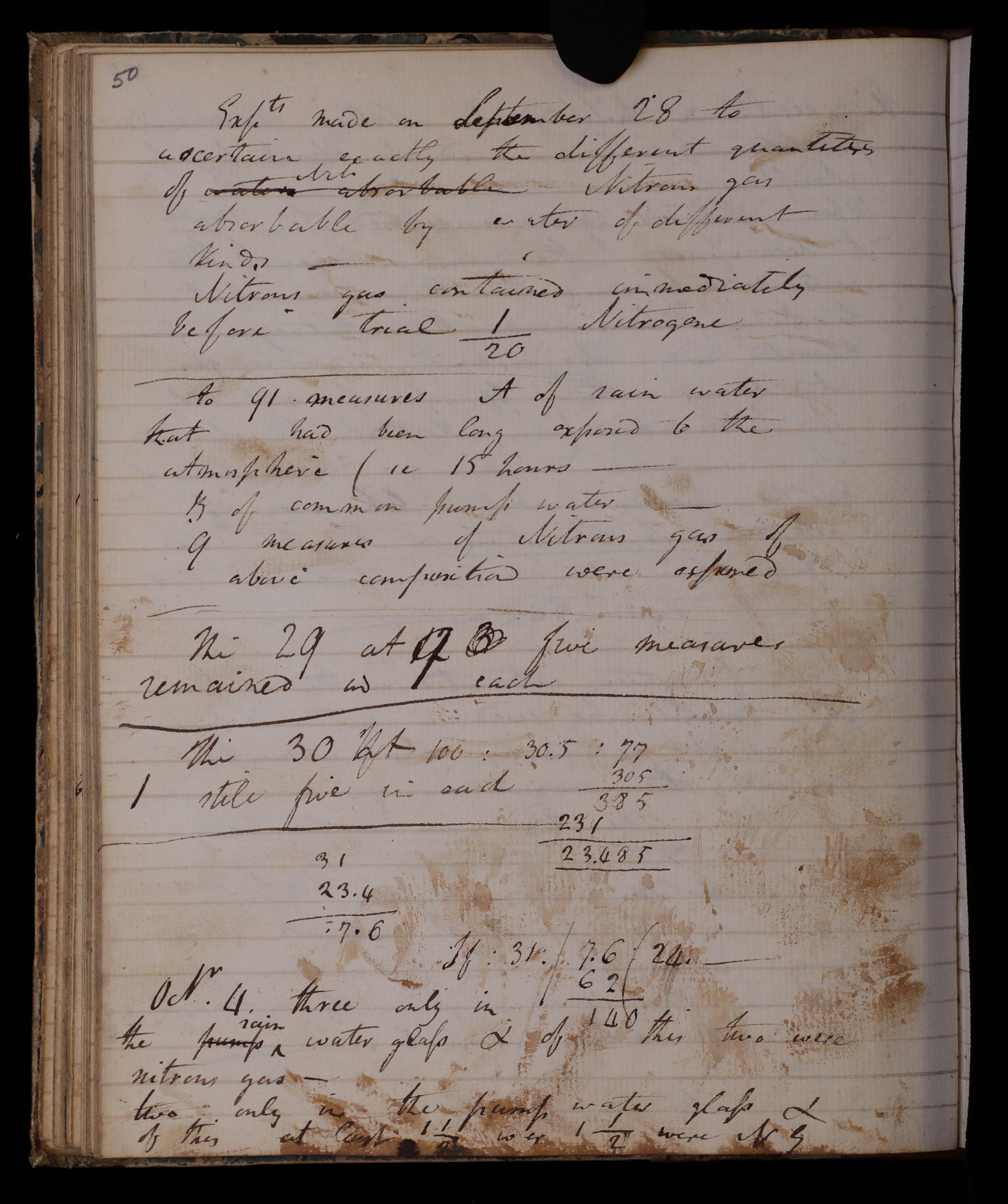

The notebooks offer a brilliant way for us to test these ideas about Davy, and to examine in more fine-grained detail the specific imaginative and philosophical contributions he made to science in tandem with his observational and experimental work. Wahida Amin has already begun to explore the ways in which notebook poems like ‘Mont Blanc’ and ‘The Canigou’ offer meditations on the power and limitations of the human mind. I am particularly taken by a passage in notebook 15F, in which Davy describes the man of Genius:

[h]is eloquence is a species of enchantment. You are captivated with the majesty of his diction, with the polish of his periods; & with the splendour & pomp of his description. You forget things in words, reasoning is absorbed in feeling; you cease to regard the philosopher & you consider only the poet. (RI MS HD/15/F, pp. 11-12)

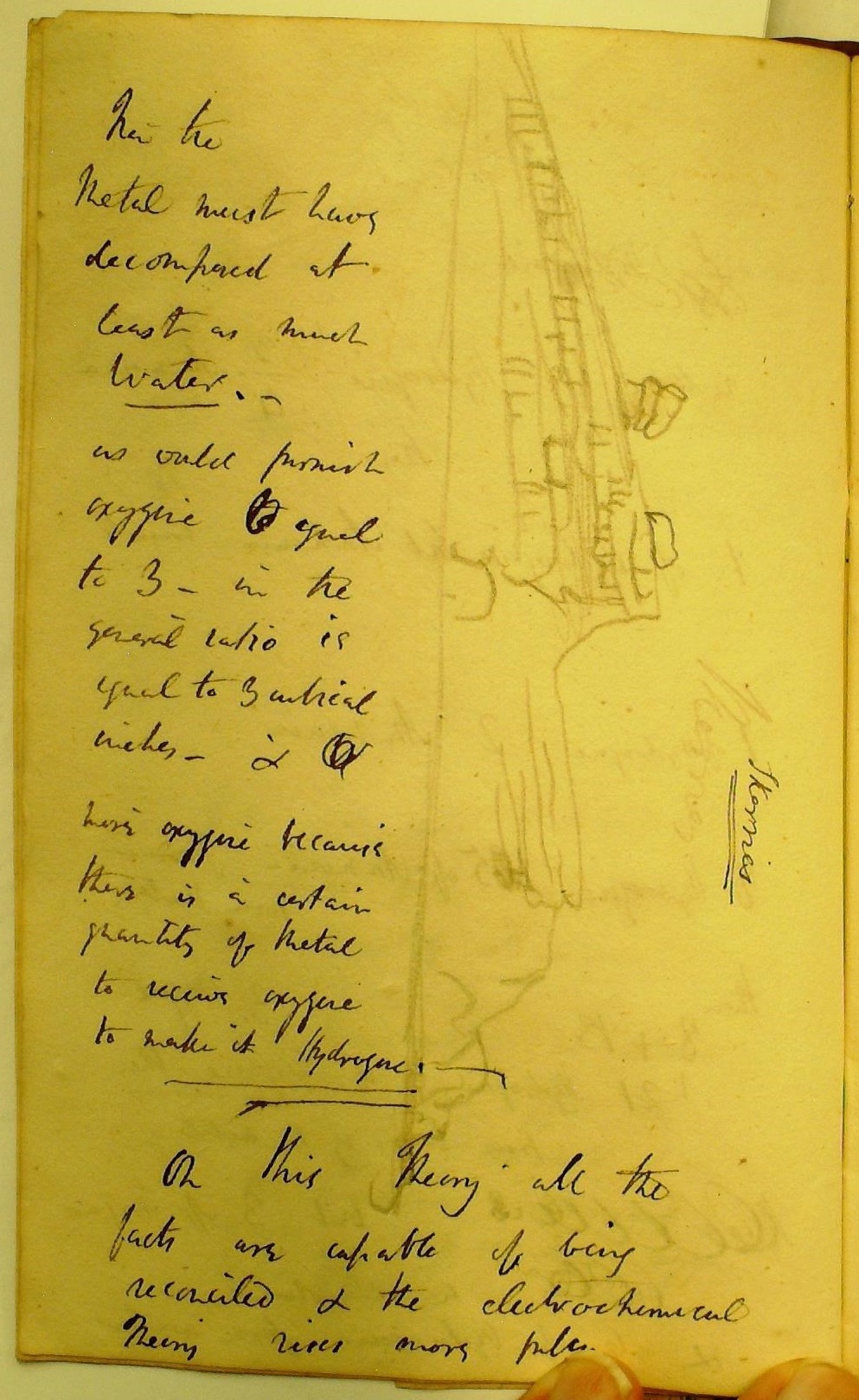

Elsewhere in the same notebook, geological sketches sit side by side with meditations on the decay of the mind and the immortality of Reason. For Davy, the almost-unimaginably vast history of the earth, with its unknown species and its dark and distant days, presented both a challenge to the human imagination and a metaphor for its powers. Exploring the notebooks, I think, offers a really exciting chance to explore the ways in which – from its outset – geology could both offer an imaginative challenge to ideas about what it meant to be ‘human’ (both in the long history of the earth, and in relation to ideas about the power and status of the human ‘mind’). And in showing a singular human mind (Davy’s) working across disciplines and ideas in this fertile way, they offer us a perhaps uniquely rich record of the emotional, aesthetic, and imaginative challenges posed by new scientific knowledge, and of the ways in which science and imagination have so often been intertwined.