Over the course of the Davy Notebooks Project, our team has come together for monthly online sessions during which we read and discuss one of Davy’s notebooks. Our reading group is always a refreshing opportunity to share knowledge and develop new ideas about the notebooks, some of which contain exciting surprises. This blog post will explore one such discovery, which links Davy’s social and literary life to one of the leading manuscript poets of his day and places him within literary manuscript culture of the period. It also explores how women’s voices, which may not be immediately apparent, in fact populate the pages of Davy’s notebooks.

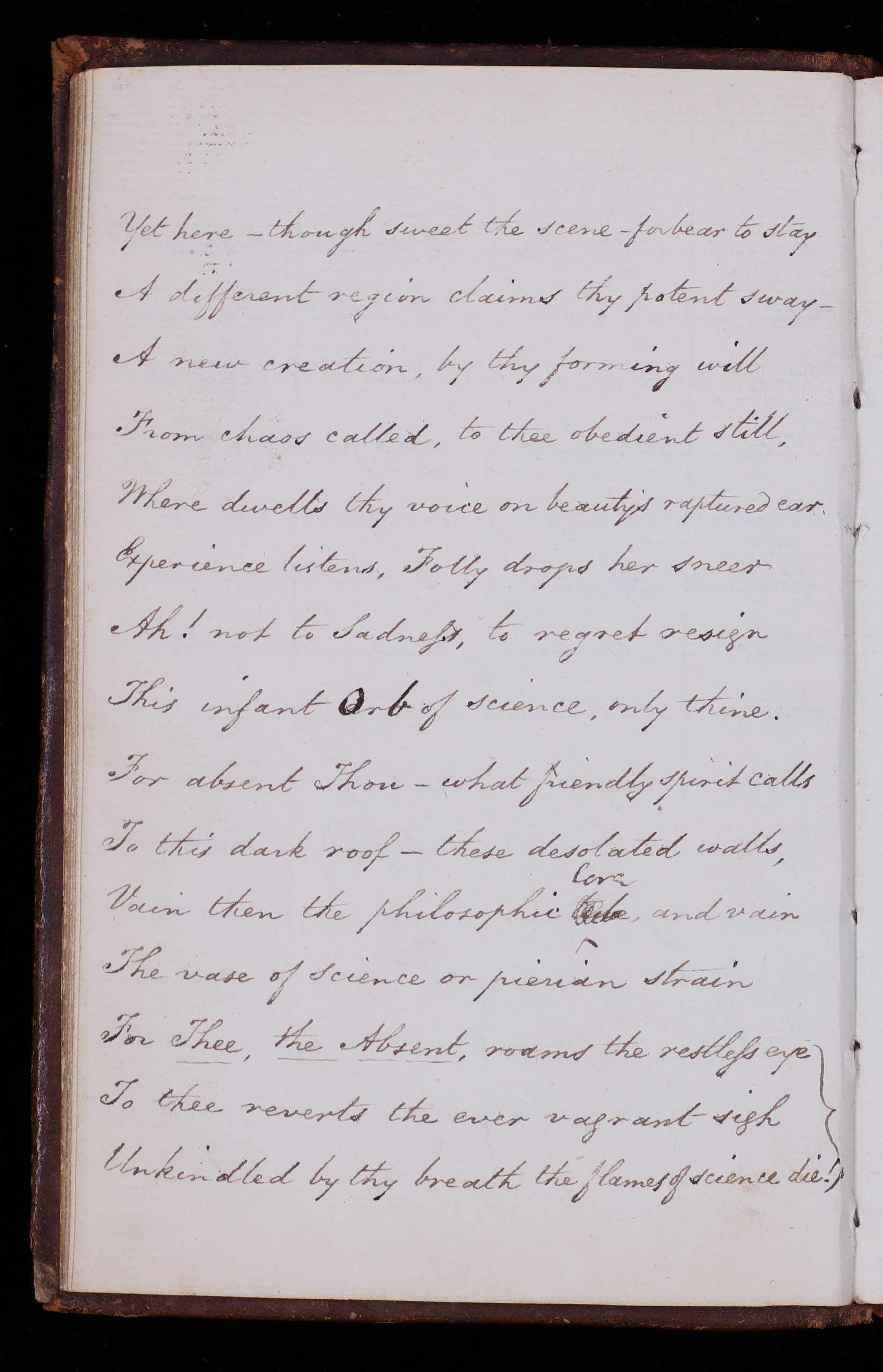

RI MS HD/13/I, pp. 10 and 11 (click to enlarge)

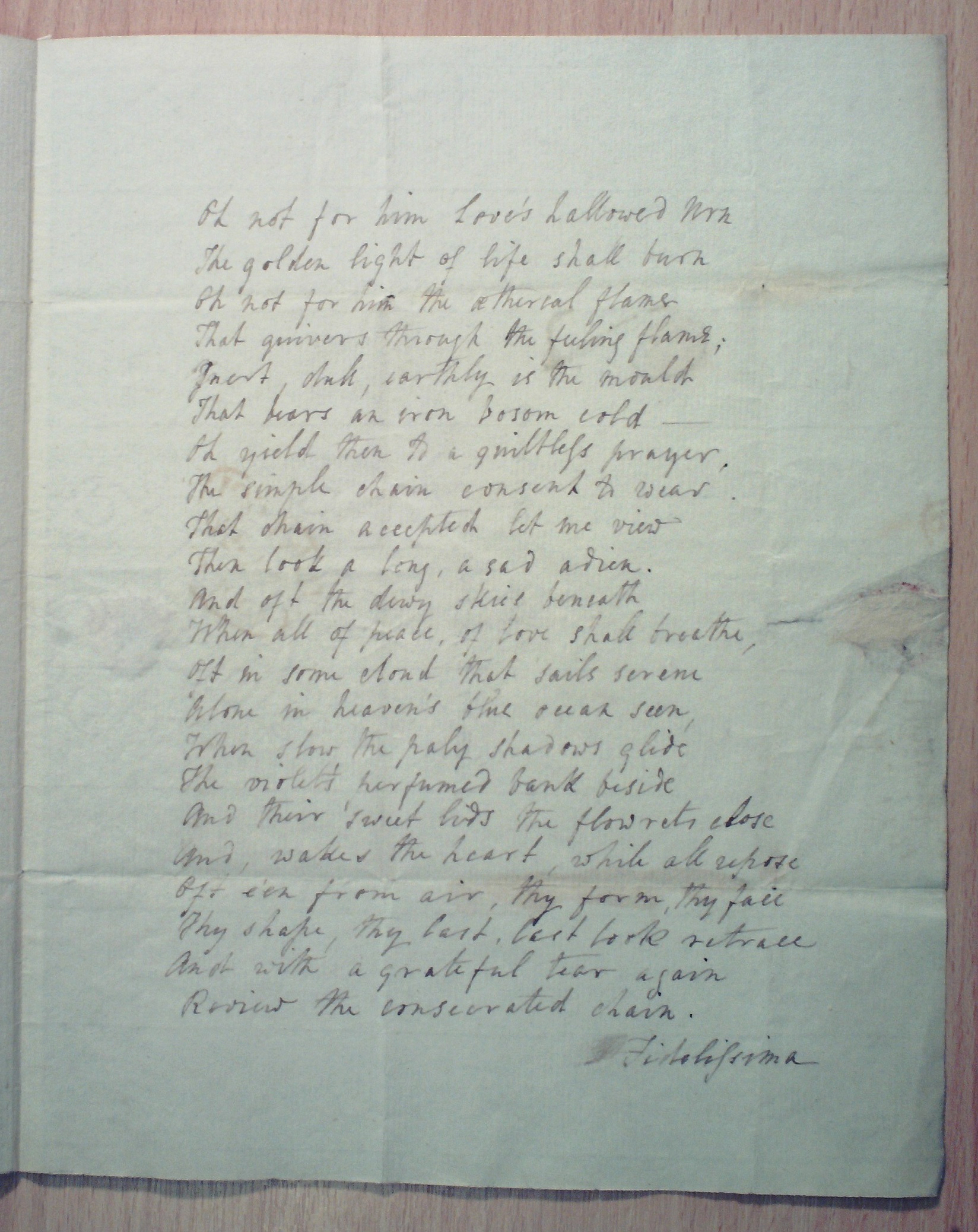

Notebook 13I opens with seventeen pages of poetry signed ‘Fidelissima’:

Thou to whom heaven its noblest gifts assigned

Blest Friend of Man, the darling of mankind,

Elect of Science on whose infant head

Truth’s angel power the full orb’d Halo spread,

Awhile farewell[.]

By now our reading group is accustomed to seeing poetry and science in the same notebook, but we were particularly struck by the poetry at the beginning of 13I, both in respect of the handwriting, which was new to us, and by the subject matter, point of view, and tone of the poetry, none of which suggested that it was written by Davy himself. The first two poems were signed, ‘Fidelissima’, i.e. ‘most faithful’. The poetry seems to be about Davy, written from a female subject position. We already knew that Fidelissima had written poetry for Davy, but could we identify her from her hand and the nature of her poetry?

We excluded Jane Davy and Anna Beddoes on the grounds of the handwriting, which matched neither of theirs. We also agreed that the poetry was not love poetry in the conventional sense, but rather written to admire Davy’s scientific knowledge, his depth of feeling, and love of nature. In the poems the author is saying goodbye to the Elect of Science and wishing him well on his journey.

Our search for poetry that matched Fidelissima’s tone and style led us to discover Catherine Maria Fanshawe, mentioned in Davy’s Collected Letters.[1] She is described in the edition’s footnotes as a poet and Davy’s friend: someone to whom he gave poems that he had written. We followed up this promising lead by comparing the lines in 13I with scans of a manuscript poem by Fanshawe, ‘A Riddle on the Letter H’, which we found online at the New York Public Library.[2]

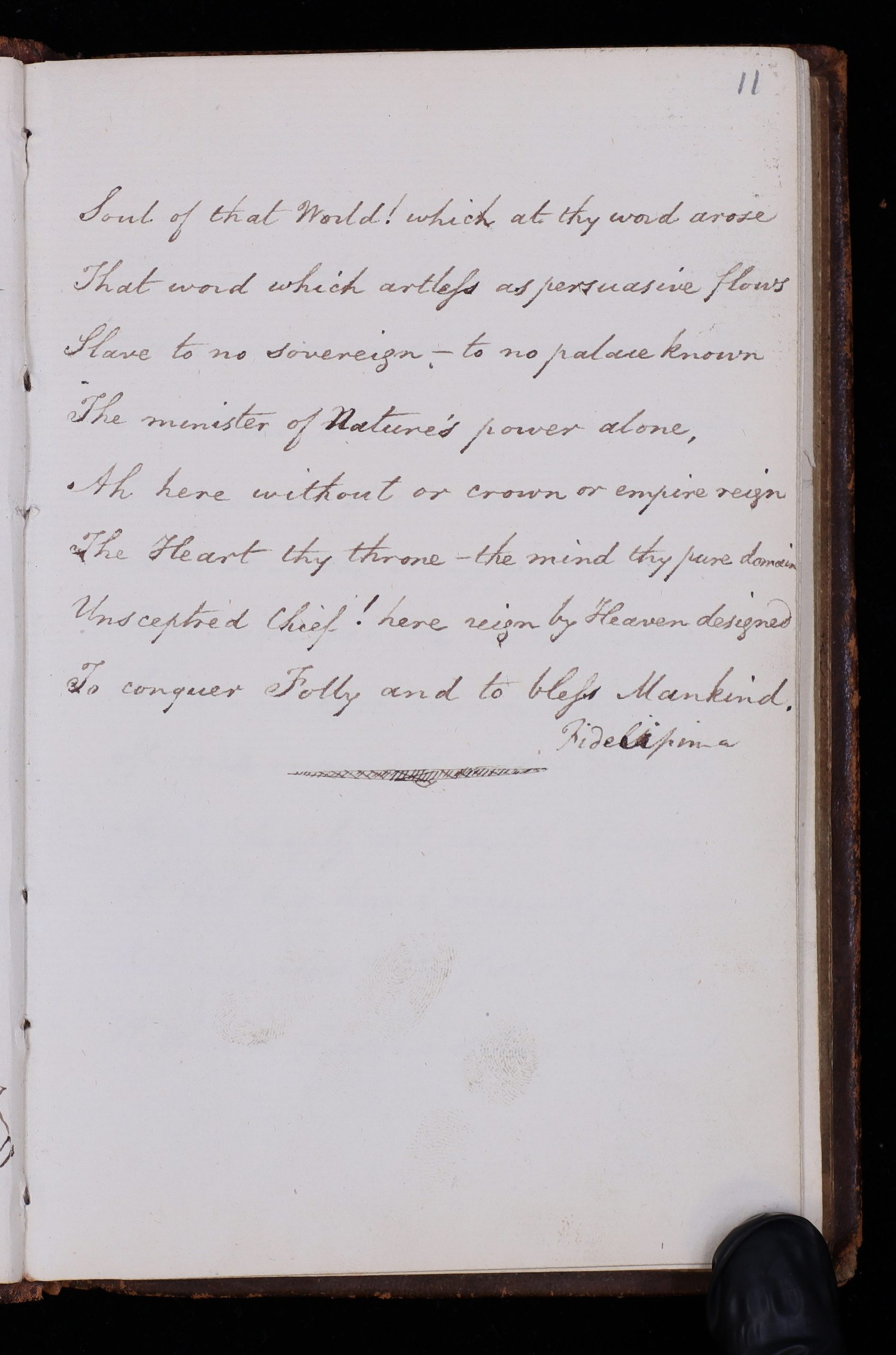

Catherine Maria Fanshawe, ‘A Riddle on the Letter H’, New York Public Library (click to enlarge)

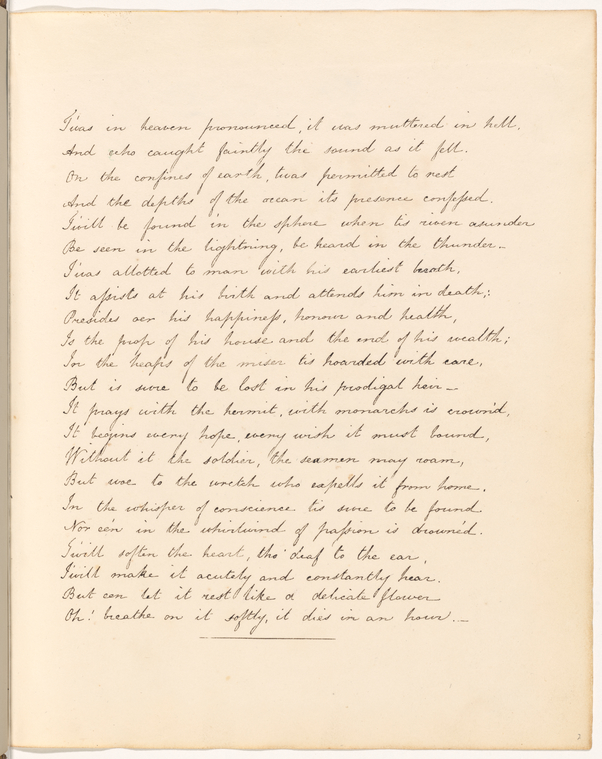

RI MS HD/13/I, p. 5 (click to enlarge)

The most telling feature of Fanshawe’s hand is her style of writing the letter ‘W’, which is identical between the two manuscripts. We were soon convinced that the hand in Fanshawe’s poem matched that in the notebook.

During our session, we found that Fanshawe had attended and written about a dinner party at Davy’s house.[3] We also established that she had written an ode to the Reverend Sydney Smith about his lectures at the Royal Institution in the early 1800s.[4] All of this led us to have confidence in our reading group discovery that Catherine Maria Fanshawe was indeed Fidelissima, and that she had copied out her poems to Davy in his own notebook.

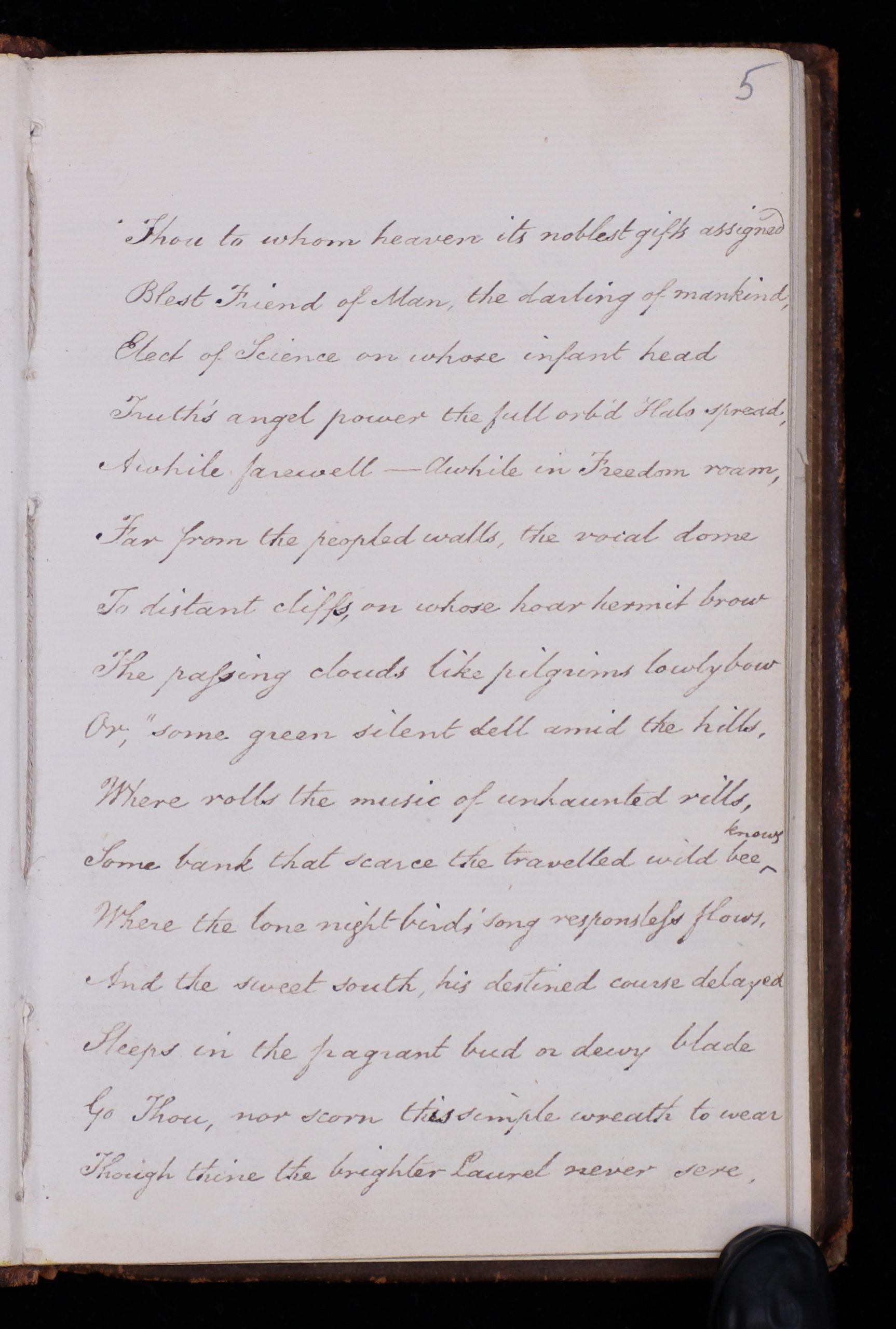

Some Davy ‘fan mail’ held by the Royal Institution (RI MS 26/H/13) (click to enlarge)

The attribution of the pseudonym ‘Fidelissima’ to Catherine Maria Fanshawe also gave a satisfying answer to some other mysteries long investigated by our team, such as a collection of ‘fan mail’ held by the Royal Institution, which can also now be traced to Fanshawe.[5]

Looking further into her life and work, it appeared that Fanshawe perfectly embodied a lost world of manuscript sociability that thrived in the early nineteenth century. While very few of her poems were published in her lifetime, they were cherished by a wide variety of readers who encountered them in manuscript form. For example, her manuscript poems were read by Sir Walter Scott, who found them ‘quite beautiful’.[6] Fanshawe’s poems clearly enjoyed appreciation both during and after her life, as seen in publications that printed substantial selections of her poems including Joanna Baillie’s Collection of Poems (1823) and Mary Mitford’s Recollections of a Literary Life (1852).[7]

Given their widespread readership, it is likely that Fanshawe’s poems were both written for and read in social situations such as salons and dinner parties. They may also have been composed through instances of personal collaboration, which we may have discovered an example of through her writing in Davy’s own notebook.

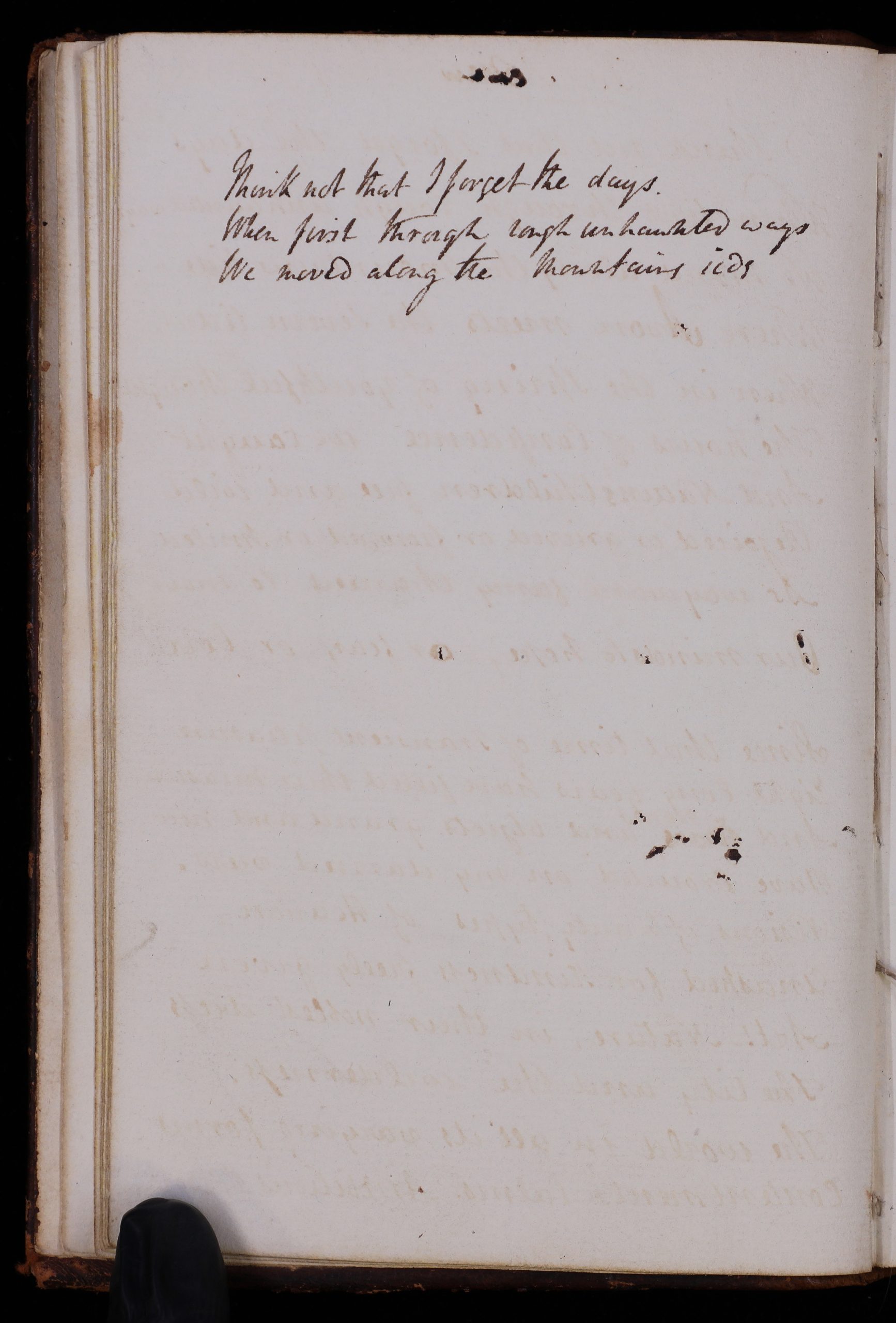

This type of collaborative working is evident in a further example of Fanshawe’s writing that we recently discovered in another Davy notebook, 13J. Dating from 1803-09, the notebook contains a mix of poetry and scientific notes. When encountering the notebook in our reading group, we quickly decided that several poems were also written in the hand of ‘Fidelissima’. One poem shows a clear example this. On p. 16, three lines of a poem are written out in Davy’s hand:

Think not that I forget the days.

When first through rough unhaunted ways

We moved along the mountains side

RI MD HD/13/J, pp. 16 and 17 (click to enlarge)

On the next page, p. 17, there appears a lengthier version of the same poem, written in Fanshawe’s hand, with a title, ‘To A[unclear]xxx[/unclear]’, and several lines added below. This implies that perhaps the pair worked side by side, or that Fanshawe may have served as Davy’s amanuensis on this occasion. Notebook 13J includes multiple poems written in Fanshawe’s hand, implying that they may have both worked with the notebook on several occasions. This type of collaborative working recalls the social writing practices of other Romantic period writers, such as the members of the Wordsworth family circle, who often worked together on manuscripts, using the handwritten pages they produced for shared reading and writing.

The discovery of Fanshawe’s presence changes how we might interpret Davy’s notebooks, proving that they were shared and social objects used by multiple authors. It also allows us to recover the story of a largely forgotten women author who left her mark on the literary world in the early nineteenth century. More than that, this discovery underlines the important role that women writers play in the notebooks’ pages, and in the formation of Davy’s literary identity. As we’re also discovering, this continued after Davy’s death in 1829, when his sister-in-law Margaret Davy and brother John used his notebooks, letters, and published works to construct his posthumous reputation.[8] Fanshawe’s proven readership, despite not seeking publication, may also say something about how Davy circulated his own poems in manuscript.

—

[1] The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, ed. by Tim Fulford and Sharon Ruston, advisory eds Jan Golinski, Frank A. J. L. James, and David Knight, assisted by Andrew Lacey, 4 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

[2] Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle, The New York Public Library, ‘A Riddle on the Letter H’, (1820-1831) <https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/c1d43830-44c2-0135-67df-799aec126ddb>.

This poem by Fanshawe was long incorrectly attributed to Lord Byron, a fact that is clarified along with a printing of the poem in the posthumous The Literary Remains of Catherine Maria Fanshawe (London: Basil Montague Pickering, 1876).

[3] Literary Remains of Catherine Maria Fanshawe also contains ‘Fragment of a Letter’, which gives an account of dining at Davy’s alongside Madame de Staël and Lord Byron in a small party (pp. 56-59).

[4] Literary Remains of Catherine Maria Fanshawe, ‘Ode’, pp. 45-49.

[5] RI MS 26/H/13; Sharon Ruston wrote about these letters in a blog post in 2012.

[6] Courtney, W. P., and Rebecca Mills. ‘Fanshawe, Catherine Maria (1765–1834), poet.’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004) <https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-9147>.

[7] Joanna Baillie, A Collection of Poems: Chiefly Manuscript, and From Living Authors. Edited for the Benefit of a Friend (London: 1823), pp. 65-77, pp. 167-85; Mary Russell Mitford, Recollection of a Literary Life, or, Books, Places and People (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1852), i, pp. 249-65.

[8] Ellie Bird was awarded the Women’s Studies Group 1558-1837 Bursary in 2023 to examine Margaret’s notebooks at Keele University Special Collections and Archives.