Dia dhaoibh agus fáilte romhaibh go léir!

In 1805 and 1806, Humphry Davy was lucky enough to visit one of the most beautiful places on earth: Ireland. Davy documented his Irish tours in four notebooks (15A, 15B, 15D, and 15G) but his focus throughout is firmly upon images rather than words. Photographic technology was still very much in its infancy – Davy and his friend Thomas Wedgwood had found no way to stabilize the images they had captured and prevent them from continuing to react with daylight, and it would be twenty years before Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the world’s first surviving photograph – so the only way that Davy could record the views he saw and the landscape he travelled through was with paper and pencil or ink.[1] The sketches in Davy’s notebooks record his journey around the Irish coast, telling the story not just of his tour but also of his passion for geology and for understanding the composition and structure of the landscape.

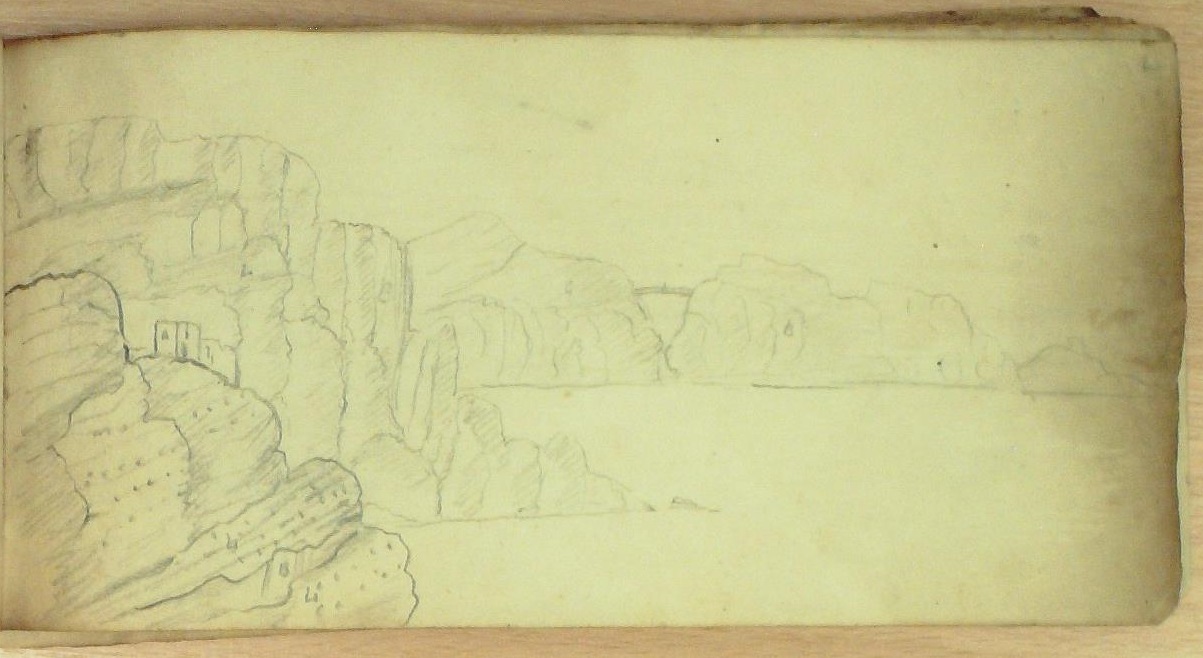

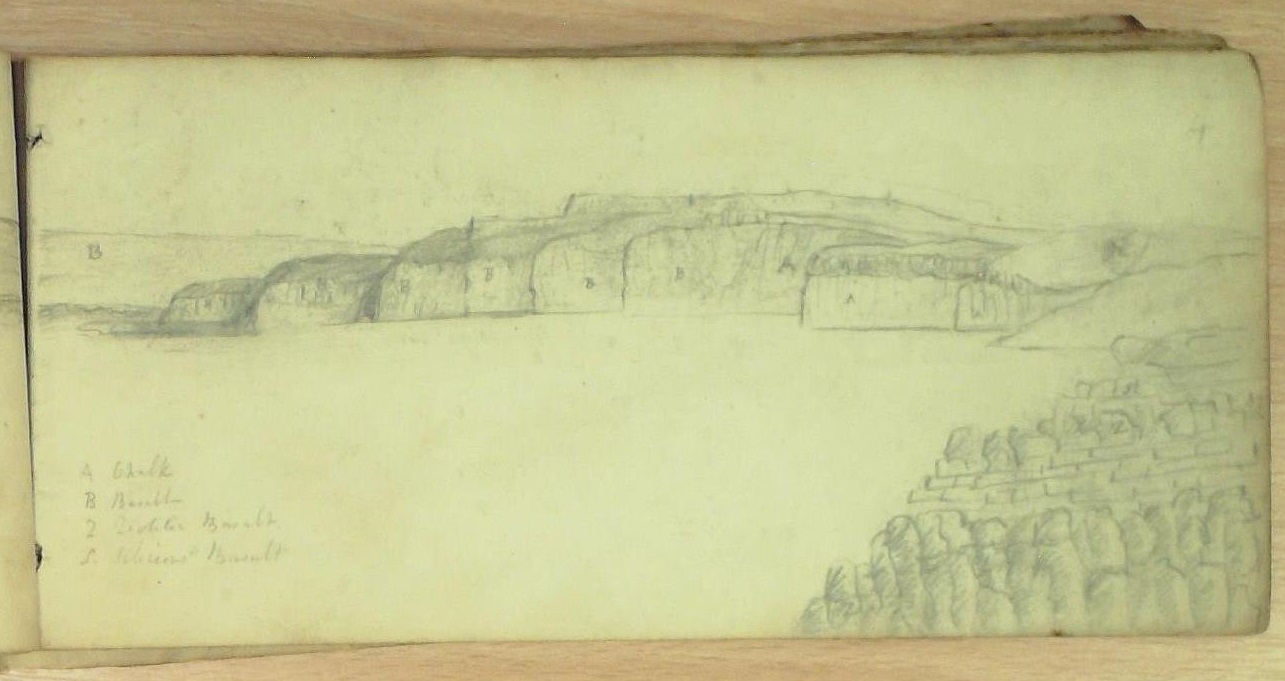

For his excursion to Ireland in the summer of 1806, Davy was accompanied by William Payne, his laboratory assistant at the Royal Institution and (at least for part of the trip) by the geologist George Bellas Greenough (1778-1855). Davy had probably first met Greenough in Penzance in August 1801, and the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) was their mutual friend.[2] In 1807, Davy and Greenough were among the founder members of the Geological Society of London, and the drawings and commentary in Davy’s notebooks from his Irish tour capture his growing enthusiasm for this branch of science. From Davy’s images, we know that he travelled around County Antrim, visiting Cushendall and Lurigethan, Fairhead, the Giant’s Causeway, the coast around Kinbane and Ballycastle, Carrick-a-rede, Dunluce, the Skerries, and Rathlin Island. Some of the sketches may have been consulted by Thomas Webster (1772-1844) when he completed an illustration of geological strata for inclusion in Davy’s Elements of Agricultural Chemistry (1813); although the engraving depicts an imaginary landscape designed to showcase as many rock types as possible, a basalt cliff similar to those Davy drew in County Antrim is included near the centre of the image.[3] As volunteers on Zooniverse transcribed these notebooks it also became clear that notebook 15D contains sketches of many of the same views illustrated in notebook 15A, but in a much freer and less defined style. For example, this pair of sketches of Carrick-a-rede, both of which feature the famous rope bridge first created by fishermen in 1755:

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 75 (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/15/A, p. 25 (click to enlarge)

Another pair of sketches feature Dunluce Castle, perched upon the edge of an outcrop of basalt and, more recently, used as the model for the exterior of Pyke castle, the seat of House Greyjoy, in Game of Thrones:

RI MS HD/15/A, p. 11 (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 15 (click to enlarge)

The hazy sketch of the castle on the page in 15A is easily lost in the shading of the cliffs until we compare it to the similar image in 15D. Both sketches contain some geological labelling of rock types, chalk, basalt, etc., but the sketch in 15A features more extensive labelling and more careful delineation of the rock formations.

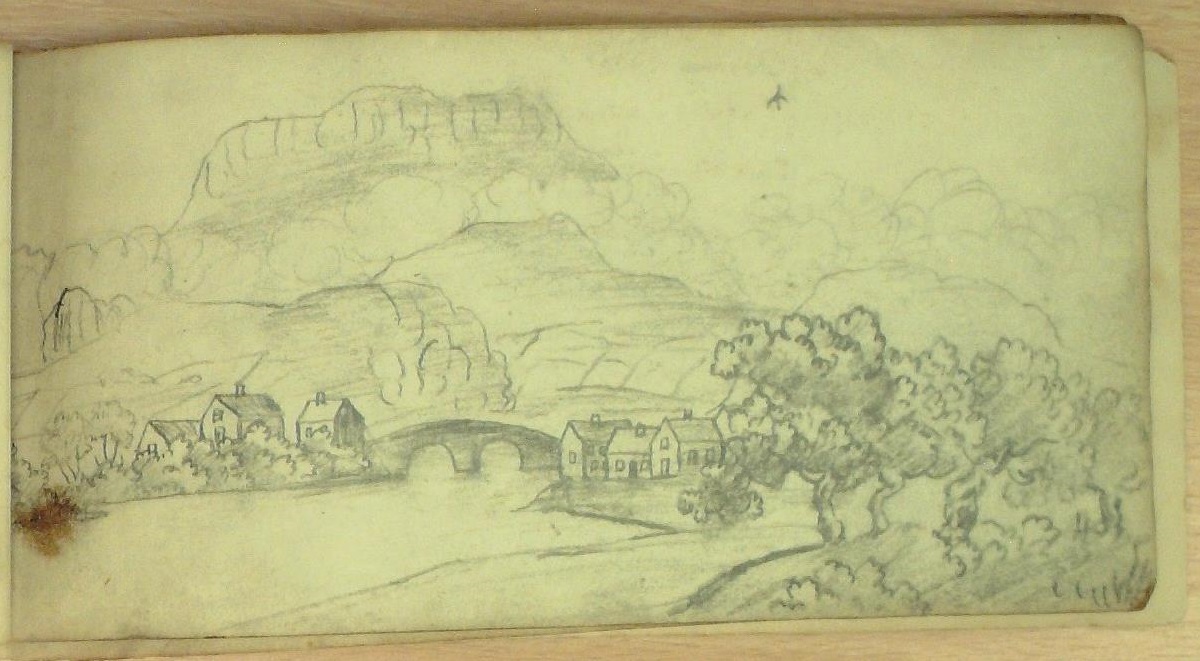

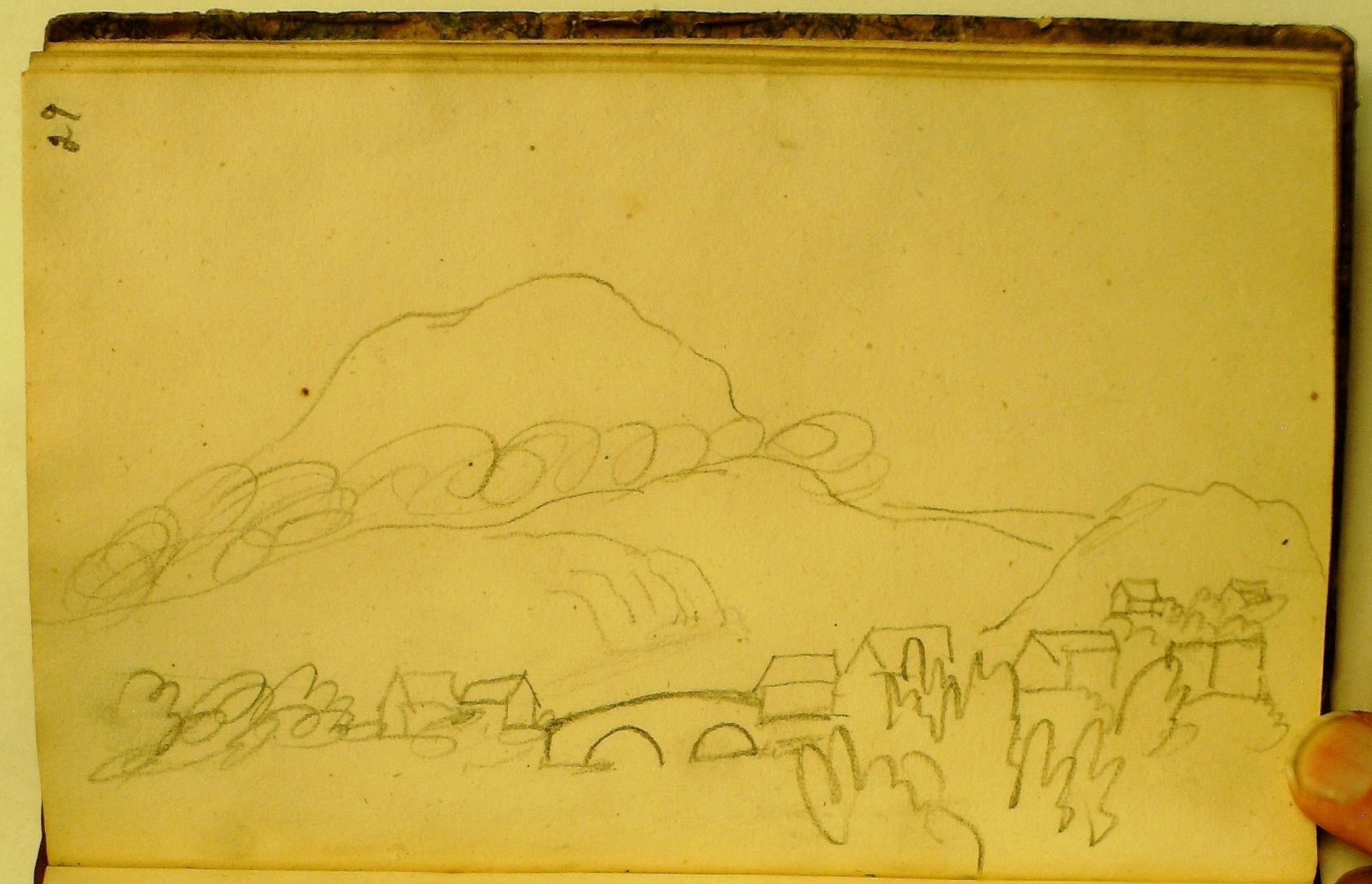

There are also at least two attempts at representing the distinctive outline of Lurigethan in 15D (RI MS HD/15/D, pp. 28, 29), both of which are from the same location and perspective as the more elaborate drawing of the mountain in 15A:

RI MS HD/15/A, p. 45 (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 29 (click to enlarge)

But the precise relationship between these sets of paired images remains unclear, and there are some intriguing dissimilarities between the drawings too. In the paired views of Lurigethan, for example, there is a noticeable difference in the configuration of the cottages that border the small bridge and in the arrangement of the foreground foliage as neat trees rather than spiky shrubs. Ideas about landscape art in the early nineteenth-century were strongly influenced by William Gilpin (1724-1804), who defined the popular aesthetic of the ‘picturesque’ as a form ‘that requires a mixture of smooth and rugged surfaces and objects for variety’.[4] Just as Gilpin ‘is not concerned with botanical accuracy’ in art, so to do the trees in Davy’s detailed sketch of Lurigethan appear a little idealistic, framing the scene with a pruned precision.[5] Once again, art and science go hand in hand here as, despite Davy’s geological focus, the scene itself seems to be being recorded in line with an artistic philosophy.

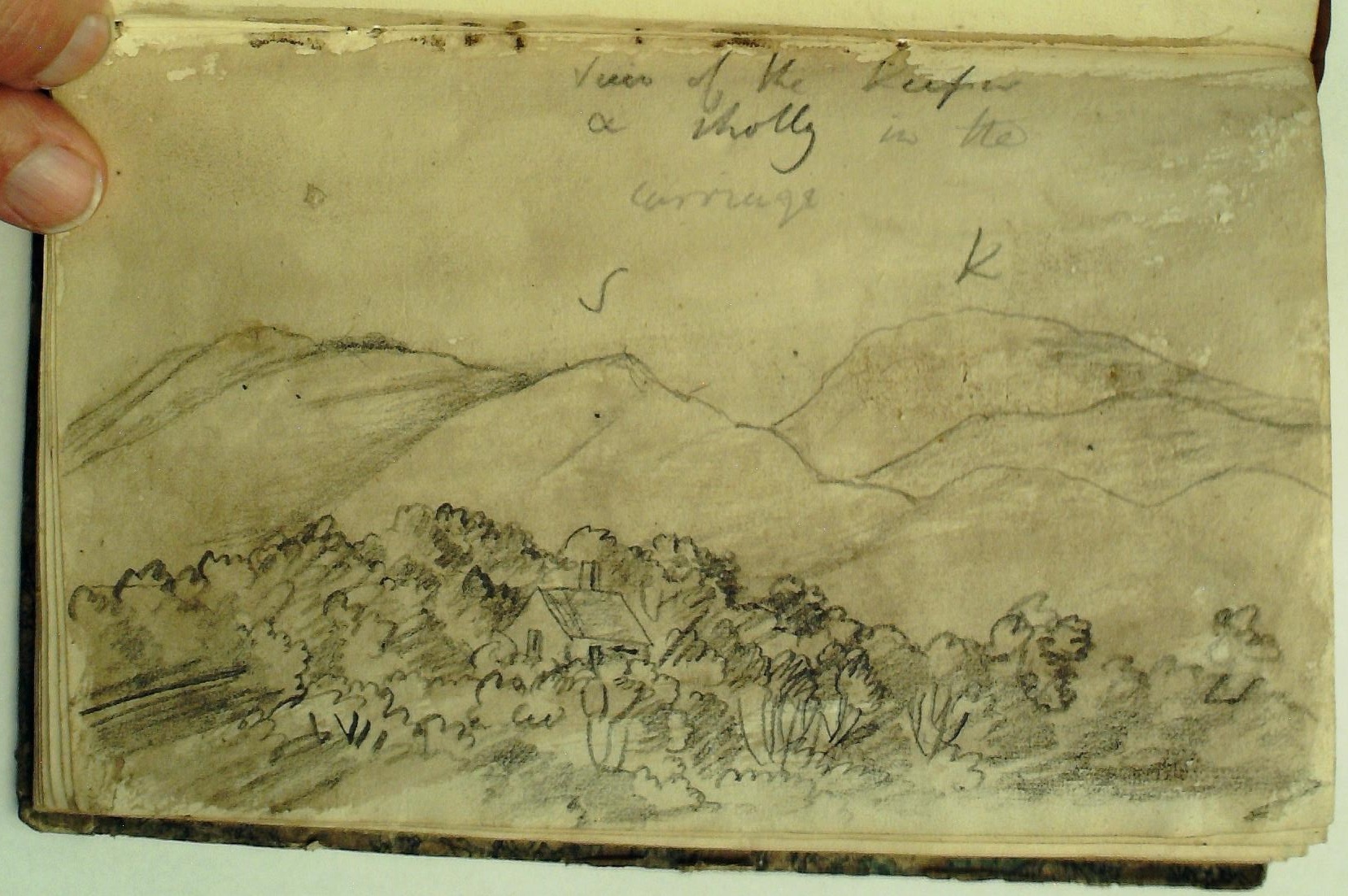

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 56 (click to enlarge)

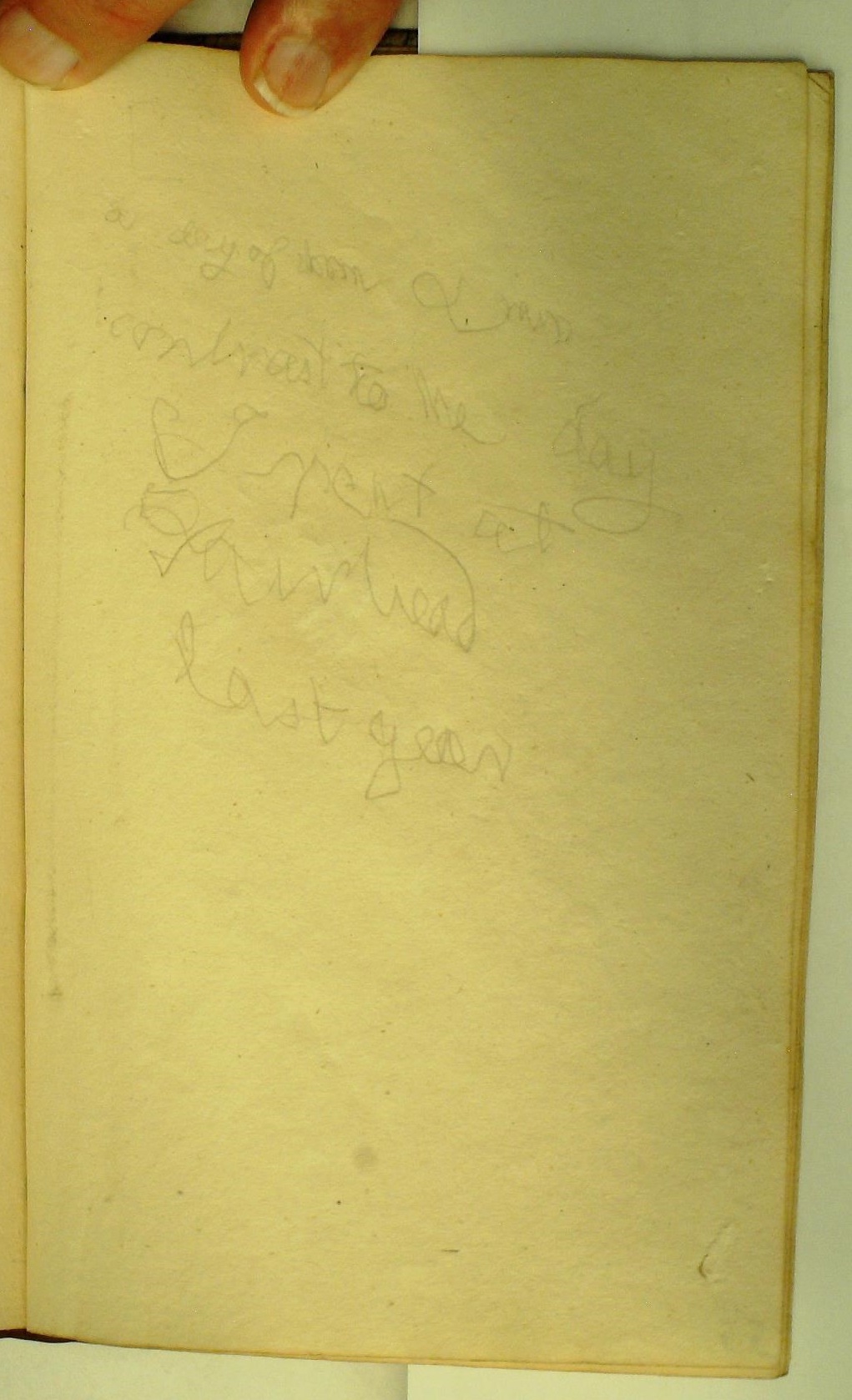

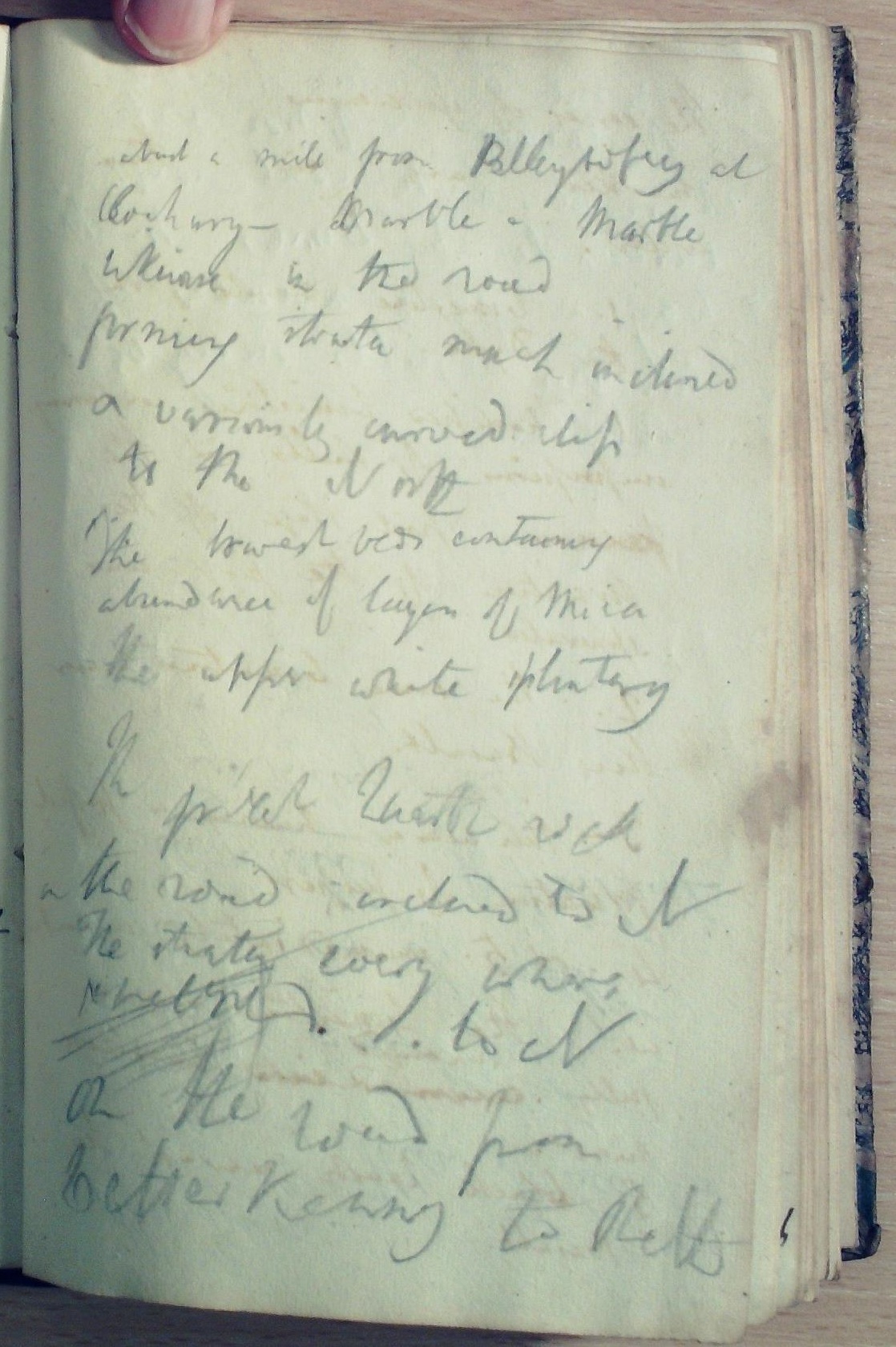

Davy’s geology notebooks also contain more tactile traces of Davy’s journey. Some particularly messy handwriting in pencil on this page might suggest that Davy was travelling while writing in this notebook. One sketch of Keeper Hill in the Silvermine Mountains of County Tipperary is described as a view ‘in the carriage’ (RI MS HD/15/D, p. 7). It is possible that the carriage was static at the time, though, as it is a rather good picture. In another notebook used during the same trip (RI MS HD/15/B), Davy again appears to have been writing while on the move on pages 96 and 111:

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 7 (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/15/B, p. 96 (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/15/B, p. 111 (click to enlarge)

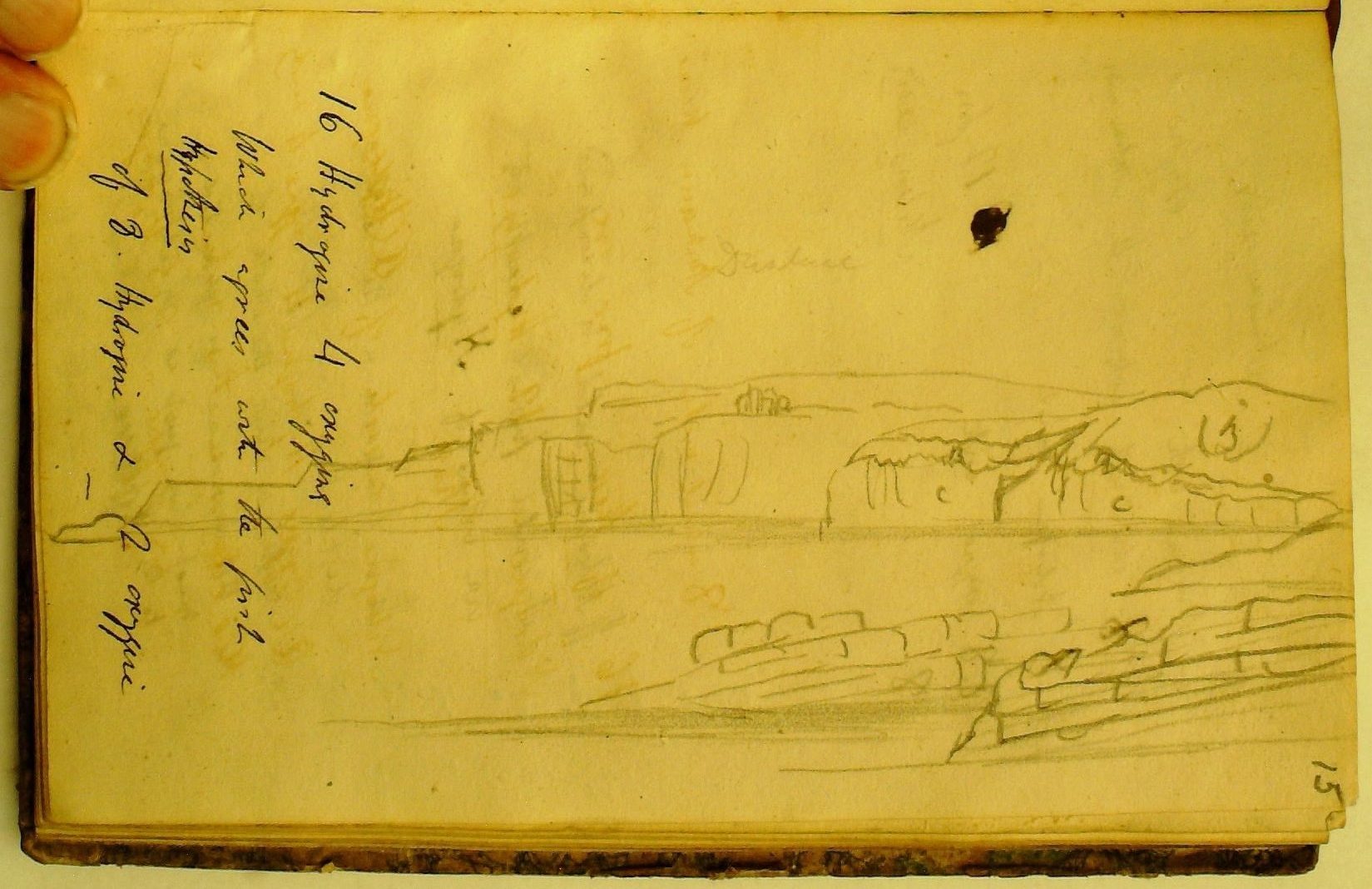

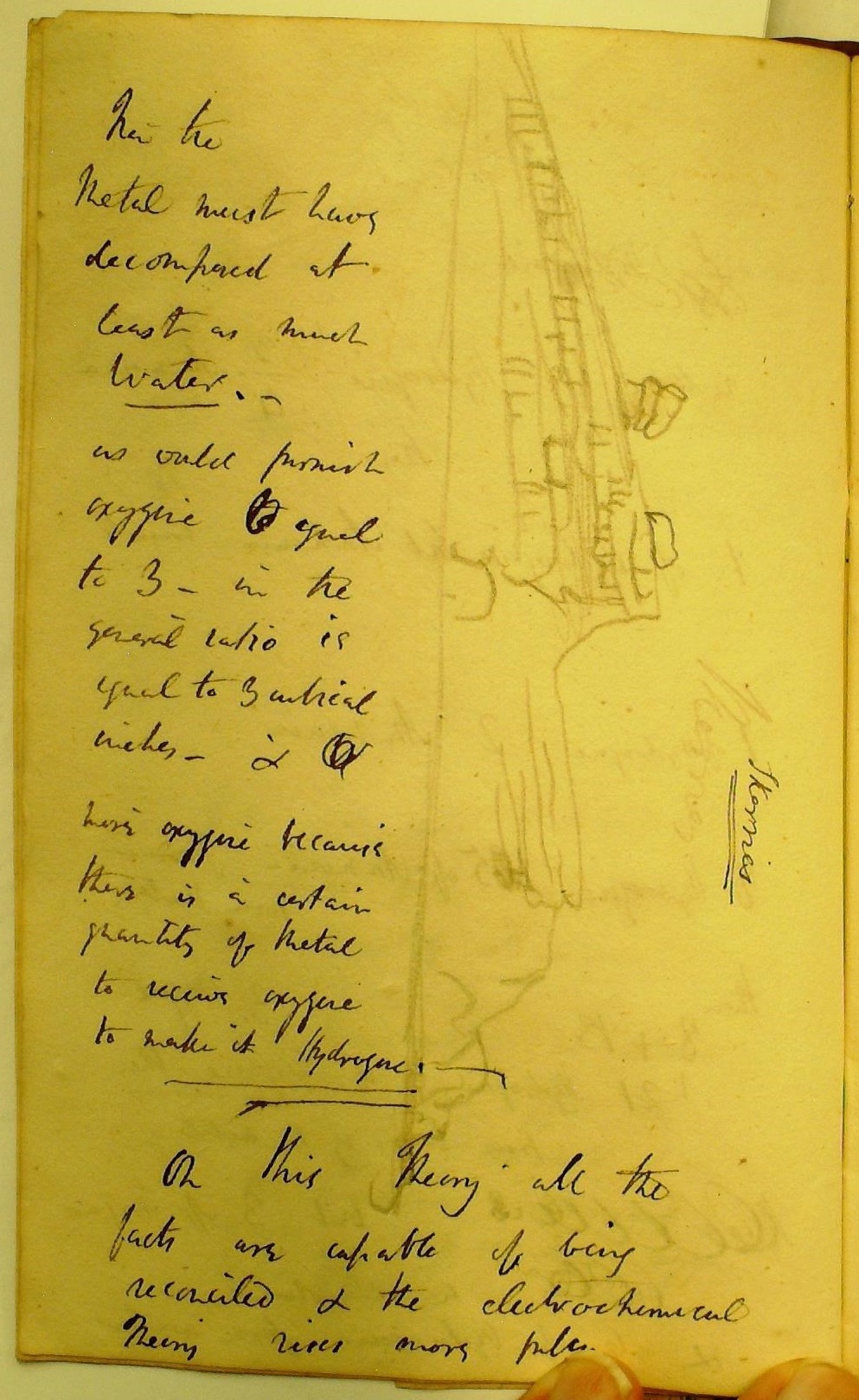

Davy first used notebooks 15A and 15D during his geological trip around Ireland in 1806, but he was evidently happy to recycle the pages of 15D when the notes were no longer of use to him: he later added details of his experiments with nitrogen and potassium over the top of his old pencil sketches, using ink this time so the new notes stood out. On page 18 of RI MS HD/15/D, for example, Davy jotted down his chemical notes alongside a sketch of the Skerries, a group of rocky islands off Portrush, County Antrim. There is some attempt to conserve the drawing – the original location has even been re-inscribed in ink – but it is clear that Davy’s focus has shifted. The chemical notes in 15D refer to ‘potassium’, an element first isolated by Davy in 1807 and that he originally termed ‘potagen’ and ‘potarchium’. The name ‘potassium’ was confirmed when Davy read his Bakerian Lecture before the Royal Society on 19 November 1807, which means that the later chemical notes must have been added to the notebook around or after this date.[6] Davy’s reuse of the paper in this notebook raises interesting questions about how he saw the sketches in this notebook: does it suggest that he no longer wanted these geological sketches or that he somehow valued them less than those in 15A? It is a reminder that Davy’s notebooks were not static objects but subject to change over time.

RI MS HD/15/D, p. 18 (click to enlarge)

We’re still in the process of examining the transcriptions of these notebooks, and many of our questions about Davy’s artistic practices and geological interests will hopefully find their answers as we study this new data. In the meantime, to all the volunteers who have helped us to find this information and who continue to contribute so much to this project, go raibh míle maith agaibh, agus slán libh!

—

[1] Thomas Wedgwood and Humphry Davy, ‘An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq. With Observations by H. Davy’, Journals of the Royal Institution of Great Britain (London: From the Press of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1802), pp. 170-74, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/b2nxduz9.

[2] ‘Greenough, George Bellas’, in The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, ed. by Tim Fulford and Sharon Ruston, advisory eds. Jan Golinski, Frank A. J. L. James, and David Knight, assisted by Andrew Lacey, 4 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), i, cxxxi; Frank A. J. L. James, ‘Negative Geology: Humphry Davy and Forming the Royal Institution’s Mineral Collection, 1803-1806’, Earth Sciences History, 37 (2) (2018), 309-32 (p. 316), https://doi.org/10.17704/1944-6178-37.2.309.

[3] Thomas Webster, ‘Fig. 16’, in Humphry Davy, Elements of Agricultural Chemistry, in a Course of Lectures for the Board of Agriculture (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1813), p. 172, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/fy86gwtq.

[4] Anna Burton, Trees in Nineteenth-Century English Fiction: The Silvicultural Novel (Abingdon; New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 2-3.

[5] Burton, Trees, p. 38.

[6] Humphry Davy, ‘The Bakerian Lecture: On Some New Phenomena of Chemical Changes Produced by Electricity, Particularly the Decomposition of the Fixed Alkalies’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 98 (1808), 1-44 (read to the Royal Society on 19 November 1807), https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rstl.1808.0001.