The Royal Society, of which Davy was President between 1820 and 1827, has recently acquired his Book of Common Prayer given him by his early patron, the Penzance surgeon John Tonkin (c. 1721/2-1801). Described as being well respected in the town (he served five terms as mayor), Tonkin always dressed in the tradition of the eighteenth-century professional medic: ‘cocked hat, large powdered wig, hand-ruffles, upright collar’.[1] Both the parents of Davy’s mother, Grace Millett (1752-1826), and her four siblings, died within a few days of each other in May 1757. Tonkin had been lodging with them at the time and thereafter seems to have served in loco parentis to the orphans. That support increased as he became wealthier and it extended to the children that Grace had with Robert Davy (1746-94), whom she married in 1776, and especially their first child, Humphry, born on 17 December 1778.

While the Davys were not poor, they were also far from well off. Robert Davy was a yeoman farmer in Ludgvan Parish some three miles east of Penzance. His farm at Varfell, overlooking Mount’s Bay, comprised nearly eighty acres and he seems to have employed one or two labourers. Nevertheless, as his family grew to five children in total, he clearly needed to supplement his income. For instance, in August 1784 Tonkin recorded buying some wreck timber from Robert Davy, a traditional Cornish way to make some extra money. Tonkin also noted providing considerable in-kind support for the Davys. In the mid-1780s, Humphry began school in Penzance and seems to have gone to live with Tonkin in the town, who recorded all the material support he gave him.

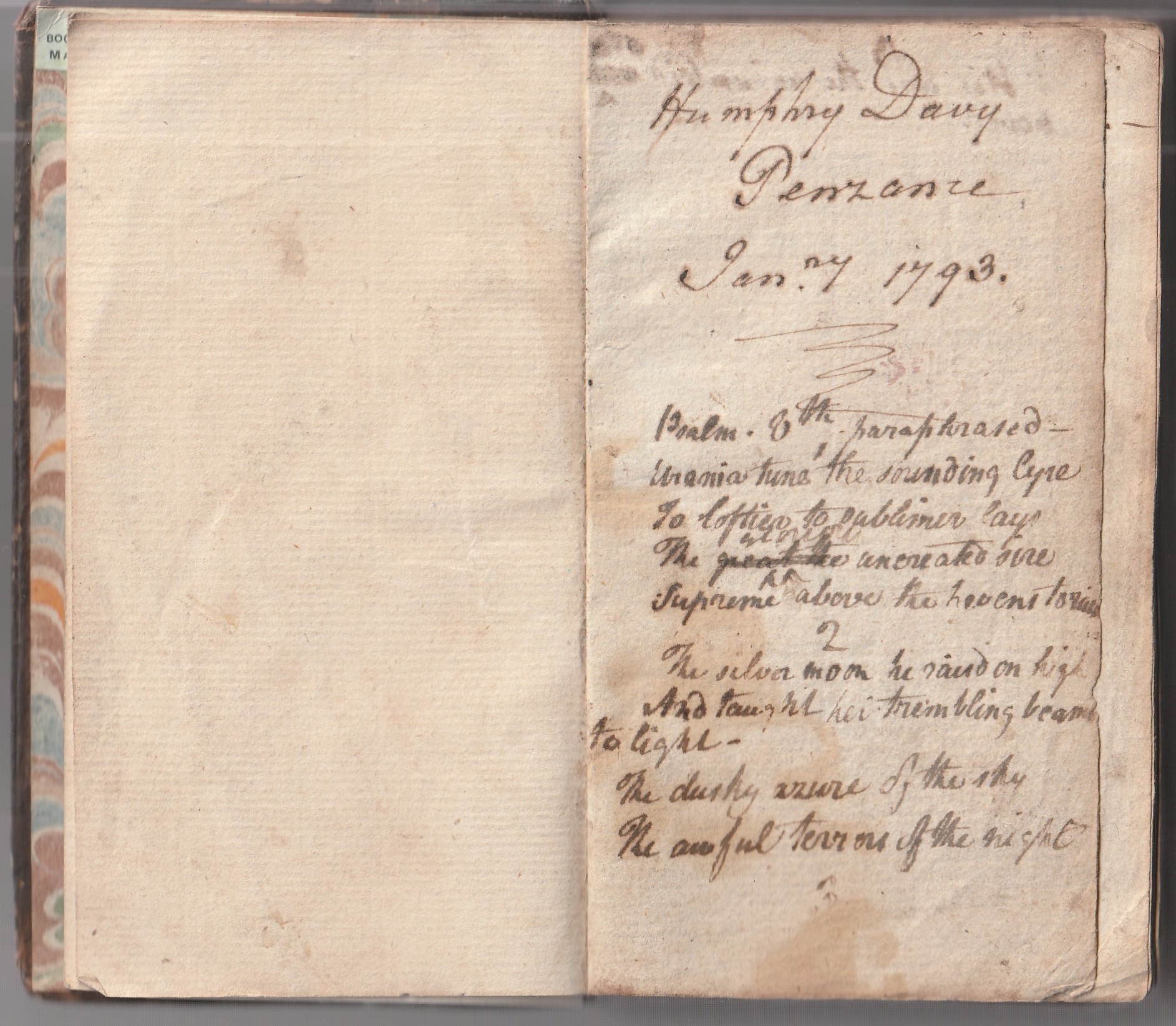

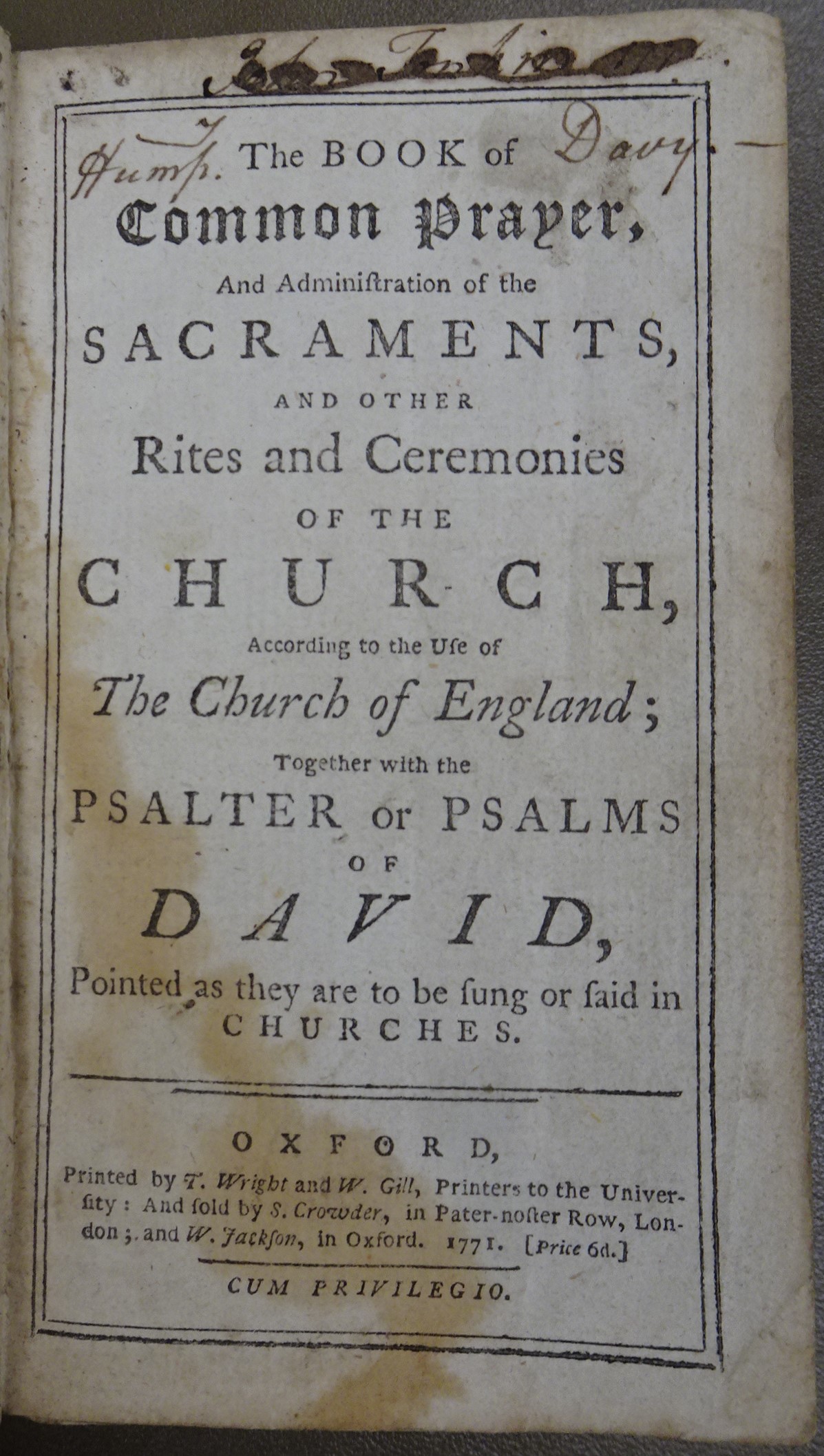

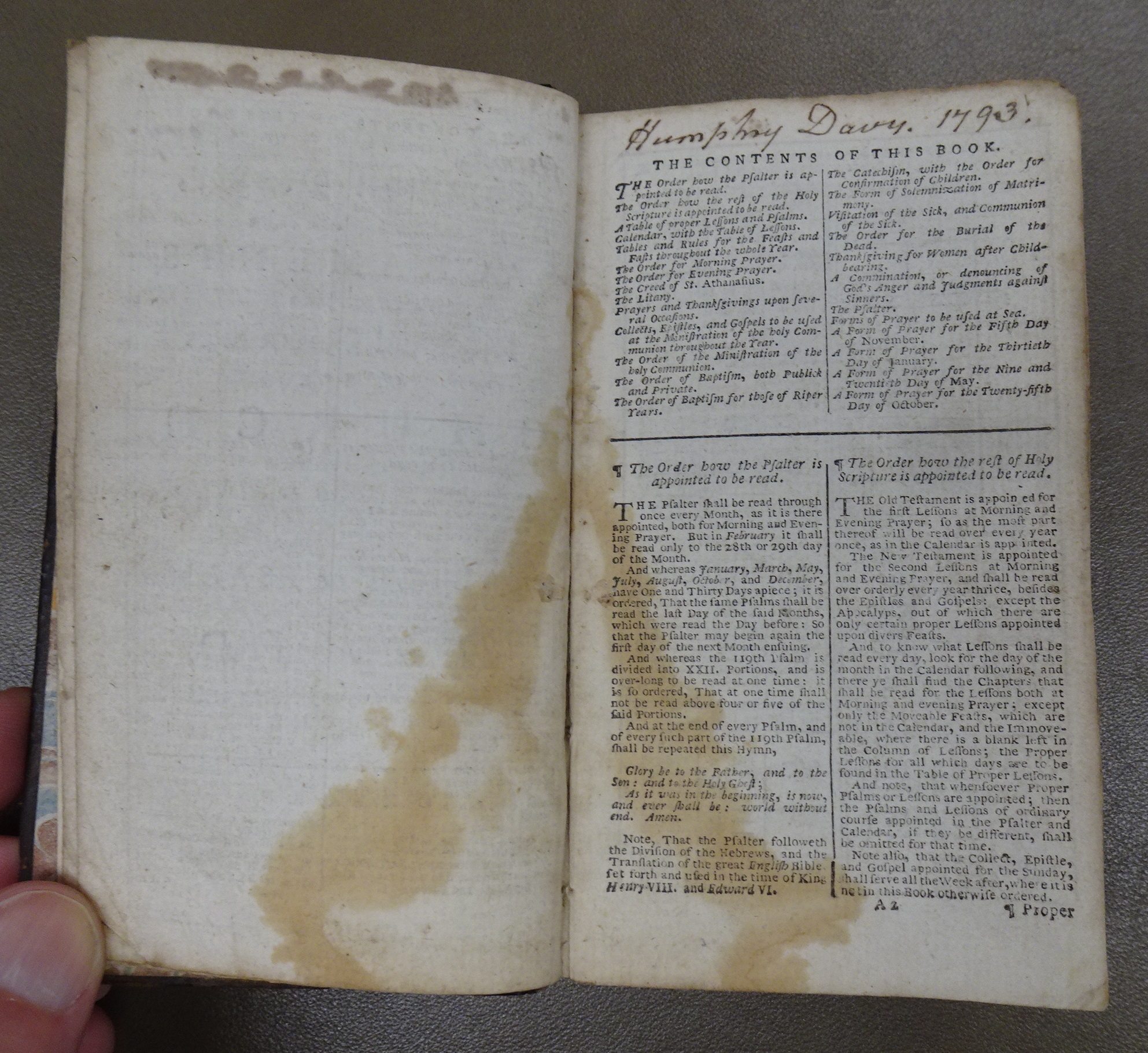

That support reached a new level when Tonkin paid the substantial sum of twenty-five guineas for the fourteen-year-old Humphry to attend Truro Grammar School during 1793. He drove Davy to his new school, dropping him off on 15 January. Among the items he gave Davy that day was this Book of Common Prayer, as Davy was to receive, for a year at least, a classical education within an Anglican framework. Though Davy never comes across as particularly devout, on the whole he conformed outwardly to the state church. This particular copy had been printed at Oxford in 1771 by Wright and Gill (printers to the University) and then cost six pence. At the top of the title page is John Tonkin’s name followed by 1771, both crossed through and replaced below by ‘Humpy Davy’ in such a way that the eye is drawn to the (presumably) unintended phrase ‘The Book of Davy’. Davy at the same time also wrote a short poem, possibly the earliest surviving one, in the book, which he claimed was a paraphrase of Psalm 8, a connection that I find rather hard to make.

(Click to enlarge)

It is still not entirely clear why Davy left school after a year. His father died at the end of 1794 just a week before Davy’s sixteenth birthday. Early the following year, his mother apprenticed him for five years to the Penzance surgeon John Bingham Borlase (1753-1813) – the substantial premium of sixty pounds once again being paid by Tonkin. Davy spent just over three-and-a-half years working for Borlase, before being lured to Bristol to work for Thomas Beddoes (1760-1808) at his new Medical Pneumatic Institution. That meant persuading Borlase to cancel the remainder of his apprenticeship which after some discussion he did, much to Tonkin’s disapproval. According to some sources, Tonkin then removed Davy from his will, but no primary evidence has so far been found to support that claim.

It is not known what happened to the book for the entire nineteenth century. According to the accompanying provenance note by Œnone Johnson, née Rashleigh (1915-2015), dated 13 October 1958, it had been given to her (in 1958?) by the important mineralogist Arthur Russell (1878-1964). Johnson was a descendent of the Rashleigh family who in the early nineteenth century were the largest landowners in Cornwall with their seat at Menabilly near Fowey on the south coast. During the mid-twentieth century, Menabilly was leased to Johnson’s close friend, the author Daphne du Maurier (1907-89). Russell had acquired part of the mineral collection of Philip Rashleigh (1729-1811), now in the Natural History Museum, so it must have seemed appropriate to give a member of the family Davy’s Book of Common Prayer. He told her that he had purchased it around 1928 from a bookseller in Penzance who acquired it from the Fox family of Falmouth; Russell had also got hold of the mineral collection of Robert Were Fox (1789-1877). No link between Davy and the Fox family has yet been found, but it does raise the intriguing possibility that the prayer book had never left Cornwall until now. Whatever its provenance, the book is emblematic of Davy’s relations with his earliest patron.

—

[1] John Davy, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Humphry Davy, 2 vols (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1836), i, 109.