RI MS HD/13/F, p. 127 (click to enlarge)

Our volunteers are helping us to transcribe all seventy-five of Humphry Davy’s notebooks and this is bringing new things about Davy to light. One of the things that has been discovered is that some of the notebooks contain expressions of Davy’s racial politics. In doing so, Davy does not speak into a vacuum, but writes about varieties of human difference and their causes, which at the time of his writing were ‘a preoccupation of intellectual inquiry’ and several paradigms were used to account for these constructed differences.[1] The discovery of Davy’s racial politics in his notebooks makes it especially critical that we confront head-on his connections to transatlantic slavery.

The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, published last year, contains short biographies of three individuals who were key in Davy’s connections to transatlantic slavery: his wife Jane Davy; her father Charles Kerr; and her stepfather, Robert Farquhar. Jane and Humphry married in 1812. Jane’s wealth, rumoured to be an income of £4000 annually and a capital of £60,000, enabled Davy to pursue his chemical research and retire from the Royal Institution professorship. Recent research by Professor Frank James has shown that Jane Davy’s money was largely inherited from her father Charles Kerr. Kerr had been a merchant and prize agent for the Royal Navy and a provider of credit, and held forty people in slavery and leased them to labour at the Royal Navy’s dockyard, the English Harbour (now the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Nelson’s Dockyard).[2]

Following the death of Charles Kerr in 1795, Jane’s mother remarried in January 1798. Jane’s stepfather Robert Farquhar of 13 Portland Place in London was an absentee slave-owner in Antigua and Grenada, who received almost £18,000 compensation from the British government.[3] Research into the connections between the Davy and Farquhar families is ongoing, but the cultural and financial links are suggested by records of ceremonies relating to births, marriages, and deaths, which show members of both families attending each other’s key life moments. While this does not mark them out as different to what we might expect of many families, it reminds us that they were members of a family. They weren’t just known to each other, but were closely interconnected on personal and social levels, and these events would have been ideal locations for intimate discussions about each other’s affairs. These sources are important given the curious absence of other source materials like letters sent between Robert, Jane, and (Jane Davy’s half-sister) Eliza Farquhar, and Humphry.

13F is dated 1795-6 and is one of the earliest notebooks belonging to Davy that we have, along with RI MS HD/21/A, which dates from 1795-7. Davy started 13F in August 1795 when he was just sixteen-and-a-half. There is also evidence that he went back to this material in summer 1798, when he was nineteen-and-a-half, and, looking at his early materialist views, observes: ‘What a revolution in my opinions since / that time, now 19 years & ½’ (13F, p. 6). The notebook is a mixture of a narrative set in Devon and Cornwall featuring Druids, with the main protagonist contemplating suicide by throwing himself into the sea; essays such as one touting materialist arguments about the dependence of the thinking powers on the organisation of the body; draft poems on happiness; an essay about the Creation, which takes a female point-of-view in arguments for creating Eve; and an essay on friendship.

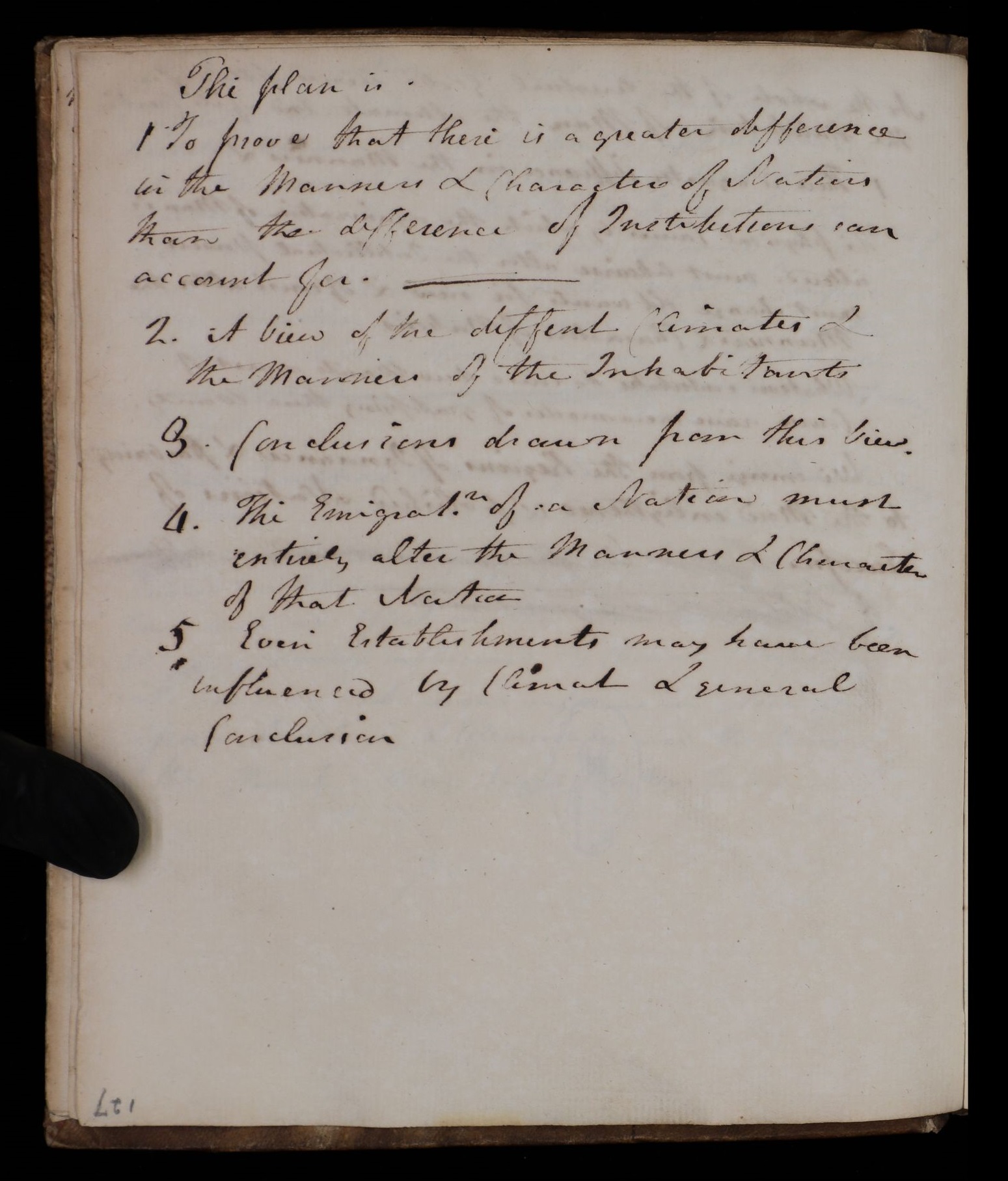

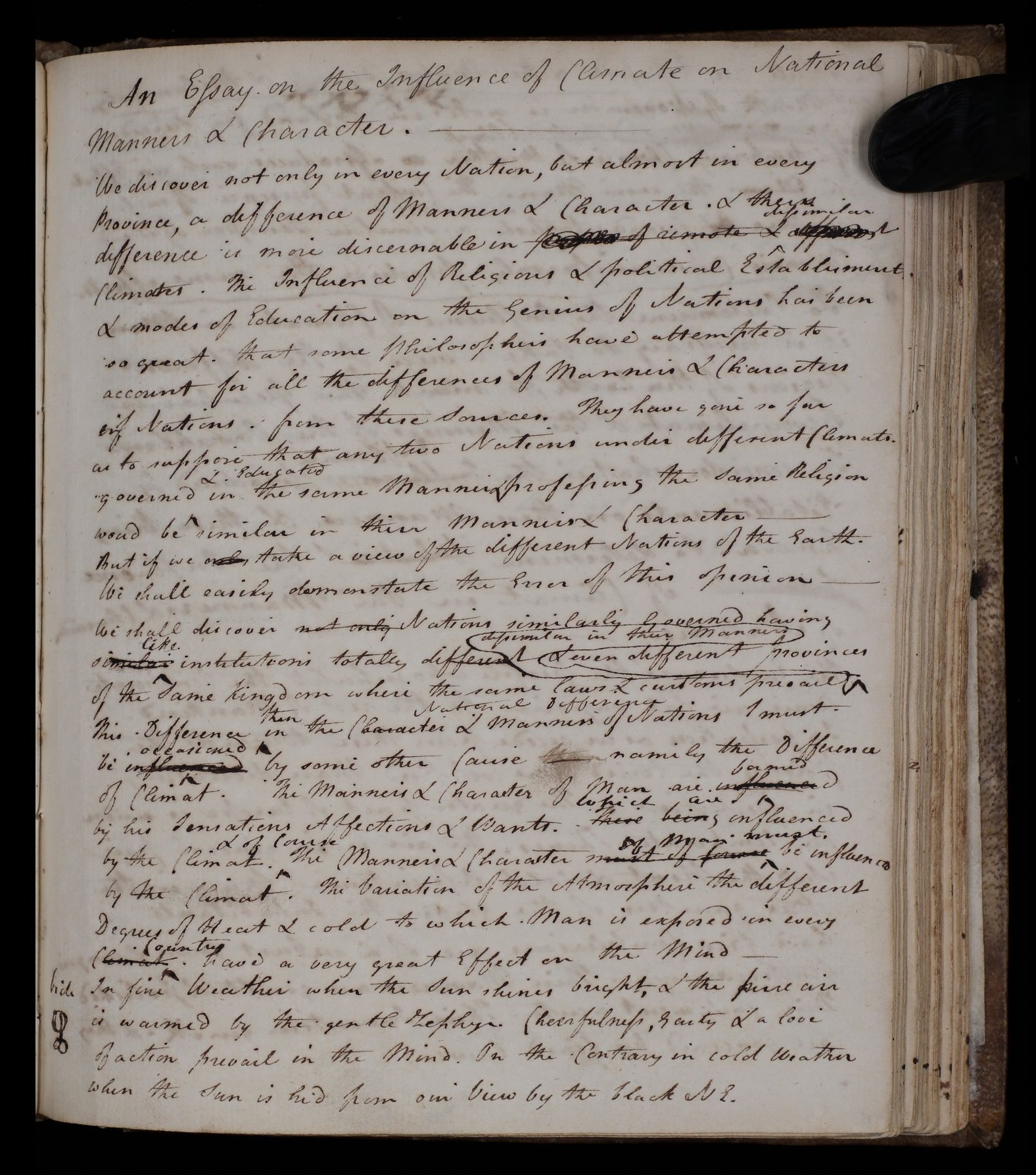

In his manuscript essay, 39 pages long and titled ‘An Essay on the Influence of Climate on National Manners and Character’, Davy engages with the arguments of David Hume in his essay ‘Of National Characters’. Hume argued that national difference was due to moral causes such as the nature of the government and ecclesiastical government, the situation of a nation in relation to its neighbours, the desires of the people, and modes of education, rather than physical causes such as the qualities of the air and climate. Davy argues that there were differences that characterised the manners and appearances of individuals within nations and provinces, and that philosophers had neglected the role that the climate, rather than customs and laws, played in influencing this difference; he argues that the ‘Difference of Climat’ is the key reason for the manners of man (p. 118).

RI MS HD/13/F, p. 118 (click to enlarge)

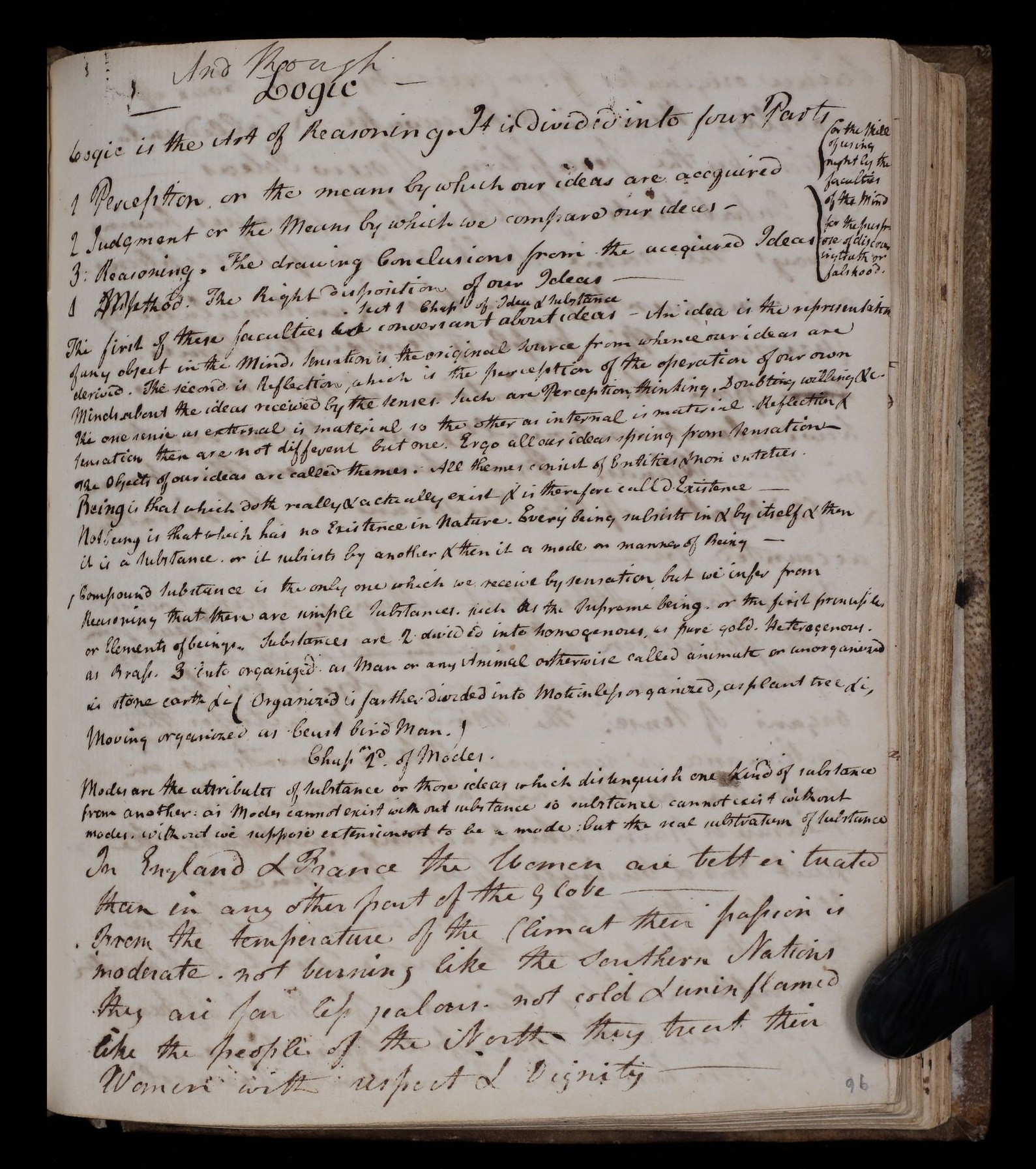

Within this worldview, Davy argues for white European superiority, and particularly the English and French nations as pinnacles of excellence. According to Davy, English people benefit from changeable weather and atmosphere, meaning that they are ‘constantly receiving new / Sensations’, and the English person’s ‘active’ and ‘agitated’ mind, reflecting the weather, protects him from ‘Torpor’, and he is ‘proud Honest / & hospitable’ (p. 115). Davy argues that Africans near the torrid zone had to breathe ‘unhealthy air’ and endure the scorching ‘Meridian sun’, with the result that their ‘Fibre is relaxed’ (p. 116). Davy argues later in his essay that constancy of heat or cold lead to ‘always the same dull round of Perceptions’, that were unstimulated by ‘curiosity’ (p. 95); Davy associates the progress of ‘Civilisation’ and ‘Science’ with European countries, where new ideas are continually excited in the minds of those living there. Discussing man’s capacity for perception, Davy argues that the mind is capable of removing or continuing these sensations (coming from the action of external objects on an individual’s organs of sense) depending on whether they are accompanied with pleasure or pain; he argues that the climate shapes how the mind filters these sensations and that those in excessively hot or cold climates are more likely to experience painful sensations, which the mind acts to remove.

RI MS HD/13/F, p. 96 (click to enlarge)

Despite arguing that emigration leads to relatively quick changes in individual character, and that there could be differences in character within nations, and that individual men could experience changes in temperament due to minute changes in degrees of hot and cold and the atmosphere, Davy undermines that sense of complexity and changeability (which works to an extent to undermine the hard and fixed boundaries of national difference) in his descriptions of nations between the northern and southern hemisphere ‘between the tropics’:

The Nations between the tropics are not only distinguished

from others by their brutal <peculiar> Physiognomy, but as well

for [?xxx] Indolence & Barbar<a>ous Manners. They have

never made the least efforts towards Civilization

& seem almost incapable of Improvement. (p. 98)

Davy’s racist ideas about the superiority of white Europeans jar with our modern sensibilities, and it is tempting to read them as being incongruous to the poetry, experiments, narratives, and diary-like entries that fill the pages of 13F and Davy’s other notebooks, and to see these racial constructions as the antithesis to Davy’s meticulously and carefully recorded chemical experiments. However, his racist thinking and ideas in 13F were part of the same material and physical object of the notebook as his writing about women, materialist arguments, and writing on friendship, and ideas circulate across different pieces of his writing. Perhaps the challenge is for us to unthink our assumptions about who Davy was and to create a more expansive vision of the man that includes crude racist stereotypes and ideas about climatic difference shaping character, and to see them as rooted within his chemical philosophy and poetic visions. We don’t know yet whether Davy’s racial politics are part of his early juvenile writing or appear in his later notebooks. As the project continues, we leave open the possibility that we might find and need to confront more examples of Davy’s racial politics. We are not sure of what we will find, but these insights will help us as we move to a more rounded sense of Davy and his reputation today.

—

[1] Roxann Wheeler, The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), p. 38, p. 37.

[2] Frank A. J. L. James, ‘Making Money from the Royal Navy in the Late Eighteenth Century: Charles Kerr on Antigua ‘breathing the True Spirit of a West India agent’, The Mariner’s Mirror 17.4 (2021), 402-19.

[3] An excellent starting point for this research is provided by UCL’s Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery Database.