Blog post by Sandra Kemp, V&A project Principal Investigator.

In a series of reviews of the 1878 Paris exhibition, John Lockwood Kipling, then curator of the Lahore Museum, compares French and British exhibition displays. He begins:

Novelty of idea is claimed for this display, but it would be hard to find a notion about exhibitions which cannot directly or indirectly be traced to Sir H. Cole, C.B., and the loan collections for which the South Kensington Museum has long been famous, and which were avowedly succursal to the exhibitions of 1862 and 1871, are the living fathers of the French idea.

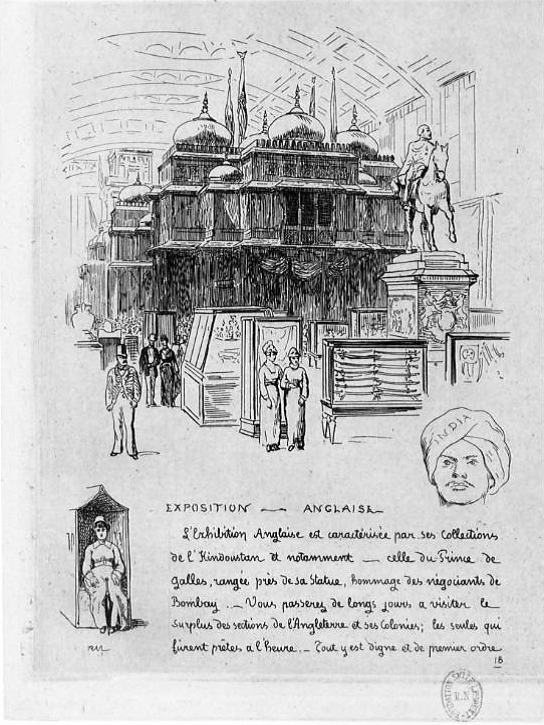

L’Exposition Universelle 1878. Lettre illustrée. Paris-Gravé 1878, p.21. The Indian Palace in the Champs de Mars during the 1878 International Exhibition.

Some pages later, however, commenting on the British display of works from its colonies, Kipling continues:

Our India, it must be confessed, makes but a poor figure in comparison; nor is what we show arranged with any approach to the method, lucidity and instructiveness that seem natural to the French.

In our first project article drawing on our case studies, André, Chiara and I are making transnational comparisons with regards to how collections, displays and visitor relations contribute to the construction of knowledge in the late 19th century.

We’re following three object journeys (and adventures) from the British and French colonies to London and Paris, and between London and Paris.

The three objects are:

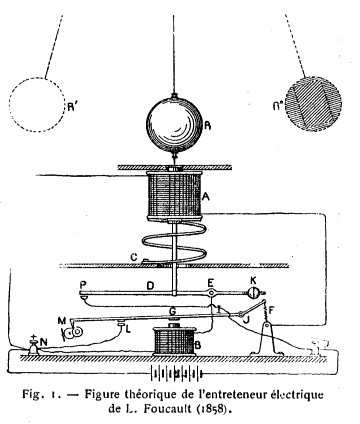

La Lumière électrique, 1e série, vol. 39, n. 1-13, 1891, p.442. Source: Cnum – Conservatoire numérique des Arts et Métiers. Foucault’s electric apparatus for keeping the movement of the pendulum continuum from 1855.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London. (Inv. Loan: Royal.461). A sandalwood Indian Writing desk, decorated in ivory, donated to the Prince of Wales during his visit to India in 1875-76.

© Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac (Inv.71.1887.155.1). A volcanic stone carved between 1350 and 1521 to represent Quetzalcoatl, god of creation and fertility in Mesoamerican cultures.

Using archival resources – such as inventories, press and journal reports and correspondence – we’re examining how these cast light on the development of knowledge, on ‘universal’ or encyclopaedic museum collections, and on the relationships between universal histories and universal museums. As Chris Whitehead (2009,12) points out:

…the emergence of disciplinarity is more than usually associated with the history of universities. But it is arguable that in the 1850s museums were the primary disciplinary drivers involved in the labour of organising and imparting knowledge through the selective organisation and display of material culture…

Comparison of the acquisition and the presentation of our three objects at the South Kensington Museum and the Trocadéro also demonstrates how contingent such developments were, as well as how dependent they were on individual curators and collectors. Exploring the history of display is one of the ways in which we can understand the strategies by which knowledge is made and disseminated. As brokers of the past in the present, curators influence how display itself influences the trajectory of works in museums and the methods by which they are disposed, presented and interpreted.

Our article investigates the movement of collections between temporary and permanent exhibitions and different types of museums. The changing contexts for the display, narratives and labelling of individual objects reflect present and past agendas on culture and society, the material impact of trade and empire, and inspiring examples of design.

6 thoughts on “Travelling objects and transnationalism”

Comments are closed.