Blog post by Chiara Zuanni, postdoctoral researcher at the V&A.

In one of our previous posts, Sandra introduced one of the papers we are working on which focuses on an interdisciplinary and transnational comparison in order to explore how museums collecting and displaying practices and international fairs contributed to the making of knowledge in the late 19th century.

In this post, I introduce another strand of our research, which we will be presenting next autumn at the Anticipation 2017 conference as part of a panel on ‘Museum Practice as Anticipation’ with Tim Boon (Science Museum) and Nick Barnard (V&A). Our paper will draw upon our case study of the Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus of 1876. We will be investigating how temporary international exhibitions of science contributed towards involving visitors in debates about the future of science itself.

The Handbook of the Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus, one of our sources for this strand of the research.

The idea of ‘internationality’ is central also to the Loan Collection, whose Handbook states that:

“It had been the intention from the first to give the Loan Collection an International character.”

However, the Handbook continues noting that:

“The mention of internationality at once suggested the idea of an International Exhibition similar in its character and arrangements to the numerous Industrial Exhibitions which have been held in various countries. A wrong impression of this kind would have entailed serious inconvenience.”

The reason for this caveat towards International Exhibitions was that the Loan Collection was organised by disciplines, not by country, and – equally importantly – it included both historical instruments (such as Galileo’s) and current scientific instruments. By organising objects by disciplines – including history of these sciences and their latest developments – and by supporting the exhibitions with a series of public lectures and those for teachers, the organisers of the 1876 Loan Collection hoped to appeal to a wider public and not just “the industrial or trade-producing interests of those countries” (Handbook).

The Loan Collection needed to have an international character, yet rather than a commercial one it aimed:

“to afford men of science and those interested in education an opportunity of seeing what was being done by other countries than their own in the production of apparatus, both for research and for instruction an opportunity which it was hoped would be of advantage also to the makers of instruments.”

It is these relations between collectors, the exhibition, scientists, visitors and manufacturers that interest us. In this strand of the Universal Histories and Universal Museums research, we are focusing on groups of objects, such as musical instruments, and observing how the 1876 Loan Collection became an opportunity to display and discuss the most recent research in acoustics, the challenges and solutions manufacturers were proposing in order to adapt instruments to this research, and the other issues and opportunities being debated by the practitioners. How could manufacturers produce a keyboard with a perfect pitch, which was also comfortable to play?

Keyboard of Bosanquet’s enharmonic harmonium, c. 1876. Enharmonic harmonium with 4 1/2 octaves tuned in 53 equal.

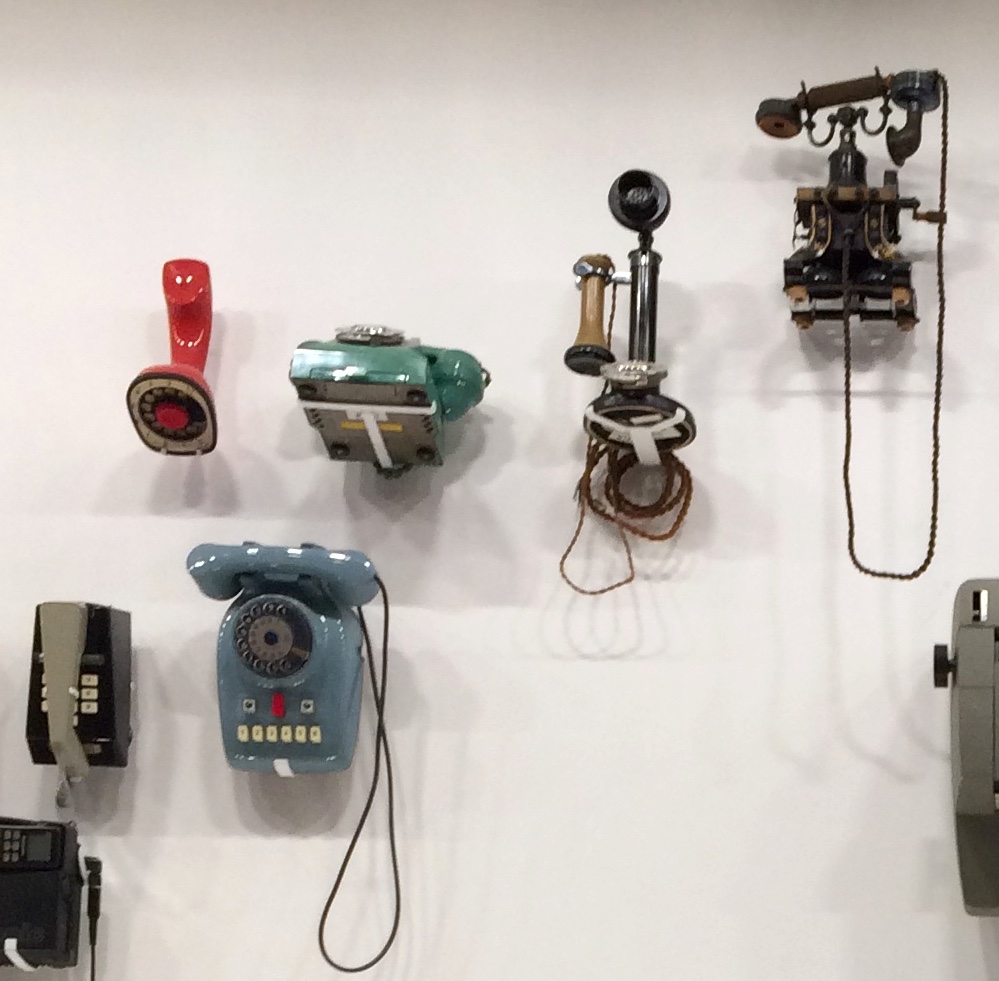

Furthermore, this material is also offering many insights about the futures that were envisioned for science at that time, and the ways in which possible futures were being presented to the public in lectures and in the press. From today’s perspective, it is fascinating to ‘hear’ a scientist emphasising how acoustic research on sound frequencies applied to sirens would have been useful to save lives in the future, not to mention that “very pretty toy” which could be easily bought in the streets and which allowed sounds to be heard at both its extremities: have you guessed what that toy was? It was the telegraph, though these ‘speaking telegraphs’ are linked to the development of ‘telephones’ (as a general reference, note that Antonio Meucci first patented a telephone in 1871, while Alexander Graham Bell patented his in 1876).

More recent evolution of the telephone on display at the Design Museum, London.