Blog post by Sandra Kemp, project PI at the V&A, and Chiara Zuanni, postdoctoral researcher at the V&A.

One of the objects we are researching is an Aztec sculpture representing Quetzalcoatl, the god of creation and fertility. This sculpture arrived in France in the early 19th century and was first displayed at the Musée Américaine du Louvre, which opened in 1851. This first display of Americas artefacts had a short life, closing in the 1870s, and ‘our’ Quetzalcoatl was subsequently transferred to the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1882. More than a century later, it returned to the Louvre, in the Pavillon des Sessions, and this is where we went to see it and document its current display.

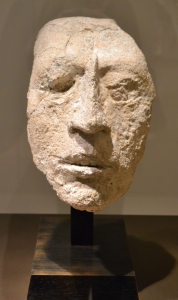

The Quetzalcoatl sculpture.

The Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas rooms in the Pavillon des Sessions were opened in 2000 by Jacques Chirac, anticipating his project of a museum of non-European art at the quai Branly. Located in one wing of the Louvre museum, the objects displayed here do actually belong to the quai Branly, the Pavillon providing a showcase of the masterpieces of these cultures and acting as a sample of the collections present in this other museum.

Pavillon des Sessions, part of the Africa section.

For the purposes of our research – as the Louvre is often considered one of the original ‘universal museums’ – it is significant to find arts from all other the world displayed here again. The fact that such arts were in fact rejected from the Louvre in the late 19th century is also interesting. More recently, the Louvre has been known for showing masterpieces of ancient classical civilisations, including the Egyptian and European cultures.

Looking at the history of museum collections is one of the ways in which we can examine how history is made, displayed and disseminated through the uses, legacies and representations of the past. In particular, we’re investigating the representation of the diversity of cultures that define human universality, the articulation of historical and anthropological approaches to the description of humanity, and the influence of social knowledge practices on the structuring of universal knowledge. We will consider this material both as initially displayed and developmentally, as new museum displays replace previous museologies; and we will compare and contrast the balance between how museums displayed their collections chronologically, geographically and thematically.

The Pavillon des Sessions is now showing non-European artefacts in the Louvre again. Around 100 objects are displayed in a series of rooms, in a striking display that emphasises their artistic aspect. Indeed, it is interesting to find such collections considered ethnographic elsewhere, displayed as art masterpieces, with little interpretation to explain their original contexts and values. Culture of origin, date, geographical provenance, material, original collection and inventory number are the standard data presented on the labels, while helpful panels display the geographical provenance of the artefacts in each room. By contrast with the Musée du quai Branly or the Musée de l’Homme, the Louvre does not discuss the cultures of origin.

- Example of a label.

- The object described in the label.

The visit to the Pavillon des Sessions has therefore given us much more food for thought. If we consider – as we are doing in our first paper – object biographies and their relevance in understanding the development of museum taxonomies and institutional remits, the Pavillon des Sessions highlights the history of attitudes towards ethnographic objects in the Louvre Museum. The context of the opening of this Pavillon is also closely interlinked with the cultural politics of Chirac and its project for a museum of world cultures (quai Branly), as mentioned above.

If we consider the idea of ‘universalities’ in museums and the future of the display of these objects, it is interesting to ask: what type of ‘universality’ is transmitted by this display? Should we privilege a display emphasising the artistic properties of objects from different cultures? Or should we try to understand the cultural values of these objects? Are these different approaches to exhibiting works irreconcilable? How can museums display challenge disciplinary boundaries whilst recognising the rich heritage and many artistic and cultural values of different objects?

On the boundaries between Asia and Oceania.