Since the beginning of our efforts to transcribe Davy’s notebooks, over one thousand people have joined in, whether to record a few lines or to make regular contributions. Every day freshly transcribed pages become available to the project team, offering opportunities to reassess what we can learn about Davy’s life, work, and contemporaries through his manuscripts.

Any researcher who has sat in an archival reading room will understand the complex challenges presented by working with manuscripts. Unpublished notebooks, diaries, and other original documents are charged objects, offering opportunities to reveal forgotten aspects of the past through discovery or reinterpretation – possibilities that Arlette Farge famously described as the archive’s ‘allure’.[1] However, attempting to extrapolate meaning from manuscripts can often be a lonely business. Squinting to decipher a word partially deleted with heavy ink or a sentence inserted between tightly packed lines often leads researchers to turn to digital tools for help – whether in the form of a camera phone to record and revisit the difficult passage later, or to share with colleagues on Twitter for second opinions.

The consensus-based platform provided by Zooniverse offers a clearer way to resolve such textual mysteries by working together with members of the public. On Zooniverse, lines are transcribed multiple times by volunteers, who are able to build on (or disagree with) the work of others as they interpret the text. The result is a polyvocal interpretation of Davy’s words, drawings, and often-tricky-to-read handwriting. Using ALICE, the app created by Zooniverse to collate and edit the results of transcription projects on the platform, members of the Davy Notebooks Project team then review, contribute to, and finalise the accumulated consensus for each page. An example of the ALICE interface can be seen below in a page from notebook 20B, in which Davy lays out the goals of his pneumatic experiments. The collaborative transcription model afforded by Zooniverse has been shown to produce higher-quality transcription data.[2] When used in conjunction with ALICE for collaborative review, this process can lead to stronger overall interpretations of original manuscript sources. Participants use the project’s online message board (called ‘Talk’) to feedback not only on difficult-to-read words, but to comment on the influences surrounding Davy’s early work – thereby helping our project to map and better understand his social and intellectual world.

Screenshot of ALICE (click to enlarge)

Thanks to our volunteers’ hard work, several notebooks have now been fully transcribed. These cover Davy’s early years and reveal a dynamic new view of his time at the Medical Pneumatic Institution in Bristol (1798–1801), an appointment given to him by the radical chemist Thomas Beddoes. During this period, Davy carried out experiments on the effects of gases, particularly nitrous oxide. The pages of these notebooks are rich with calculations and findings from Davy’s experiments. While Davy’s work at the Medical Pneumatic Institution was intended to produce new treatments for illnesses including consumption, his notebooks reveal how he tested nitrous gases on himself, often in rather unorthodox ways. For instance, in notebook 20B, Davy writes of having ‘breathed after a terrible drunken fit a large quantity of gas 2 bags & two bags of oxygen’, noting that the experiment, perhaps unsurprisingly, ‘made [him] sick’.[3]

RI MS HD/20/B, p. 95 (click to enlarge)

Davy also frequently recruited others to serve as test subjects for the effects of the gases, collaborations which he documented in the pages of his notebooks. In April 1799, Robert Southey inhaled the gas, reporting ‘giddiness’.[4] These manuscript records laid the groundwork for Davy to publish his findings in a significant volume entitled Researches, Chemical and Philosophical; Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and its Respiration (1800).[5] The text integrated personal accounts of the effects of the gas on numerous friends and scientific colleagues, including one given by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge inhaled the gas several times, the experience causing him to stamp his feet, after which he ‘remained motionless, in great extacy’ (Researches, p. 517).

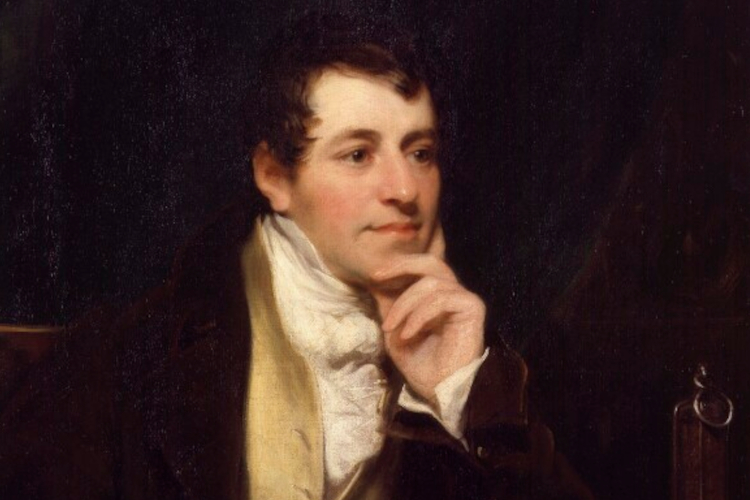

Title-page of Davy’s Researches

Davy’s writing from this period also highlights how he viewed his individual forms of experimentation as being closely linked to the achievements of other chemists and philosophers – itself a form of collaboration. In Researches, Davy noted being indebted to the ‘illustrious fathers of chemical philosophy’ and their earlier attempts at the ‘discovery of truth’, including ‘Priestley’ in this category (Researches, p. xv).

Joseph Priestley’s name is one which frequently appears in the pages of Davy’s notebooks from this period. Priestley was a chemist, theologian, and radical political theorist whose earlier work on gases had inspired Beddoes to set up the Medical Pneumatic Institution. Priestley’s Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (1774–86) detailed his preliminary discovery of oxygen and laid significant groundwork by identifying other ‘airs’, including nitrous oxide.[6] Priestley had previously been part of the scientific and intellectual circle surrounding Beddoes, a community which would later provide important patronage to Davy during his early years in Bristol. However, Priestley had been forced to leave England due to his outspoken backing of the French Revolution, having written in support of republicanism through the lens of natural philosophy, provoking public attacks from the likes of Edmund Burke. He settled in Pennsylvania from 1794 onwards.

While Davy and Priestley never met, notebook 20A records that Davy conducted ‘Experiments on the Composition of Nitrous Acid’ with assistance from his son in October 1799. Through this and further experiments, Davy built on Priestley’s earlier work on nitrous oxide, seeking to disprove the claims of the American chemist, Samuel Mitchill, who had alleged that inhalation of the gas would be fatal.

RI MS HD/20/A, p. 53 (click to enlarge)

Yet, as notebook 13H shows, Priestley’s radical revolutionary principles, along with those of Beddoes and their contemporaries, may also have held an important influence on Davy’s literary and political ideas during this period. Newly transcribed pages of this notebook reveal Davy’s propensity towards using revolutionary rhetoric in his manuscript poetry. Along with scientific and philosophical notes, notebook 13H includes a ‘Prospectus of a Volume of Poems’.[7] The poems in the ‘Prospectus’ offer a healthy dose of amorous poetry in fair copy, yet numerous other poetic fragments in 13H move in a different direction. These poems draw on the language of freedom, rebellion, and anti-hierarchical principles that were prominent in pro-revolutionary literature of the period. In one poem, ‘the radiance of the sun of truth / […] Calls the world to arms’, awakening ‘liberty’.[8] Elsewhere, ‘the Son of Liberty / uplifts the sword / To cut the chains of nations with the blood / of Tyrants & Slaves to fertilize / The happy earth’.[9]

RI MS HD/13/H, p. 38 (click to enlarge)

While this largely unpublished body of Davy’s writing requires further consideration as a distinct strand of his work, these manuscript poems clearly highlight Davy’s experimentation with radical ideals during his early years. They point to Davy’s engagement with an important form of political and literary thinking specific to the 1790s milieu in which he lived, worked, and experimented – an ideology of revolutionary enthusiasm that would all but disappear from the pages of his notebooks during his later years at the Royal Institution. These poems, alongside his experiments from the same period, display Davy’s collaborative propensities, as well as his ability to build on and extend the ideas of his predecessors, contemporaries, and patrons during his time in Bristol.

As further notebook pages are transcribed by our volunteers each day, countless new connections and important discoveries relating to Davy’s notebooks are coming to light. Every line of text transcribed represents not only an engagement with Davy’s scientific and poetic experiments, but also an act of collaboration between transcribers and researchers.

To join us as a volunteer transcriber for the Davy Notebooks Project, visit our Zooniverse page here.

—

[1] Arlette Farge, Le Goût de l’archive / The Allure of the Archives (1981).

[2] Samantha Blickhan, et al. ‘Individual vs. Collaborative Methods of Crowdsourced Transcription’, Journal of Data Mining and Digital Humanities, Episciences.org (2019).

[3] The quoted text was transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers. Here and hereafter, we are grateful for their contributions.

[4] Quoted text transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers.

[5] Humphry Davy, Researches, Chemical and Philosophical; Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and its Respiration (London: Joseph Johnson, 1800).

[6] Joseph Priestley, Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air (London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1774–86).

[7] Quoted text transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers.

[8] Quoted text transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers.

[9] Quoted text transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers.