Gregory Tate is a Senior Lecturer in Victorian Literature at the University of St Andrews specialising in nineteenth-century literature, and a member of the Davy Notebooks Project Advisory Board

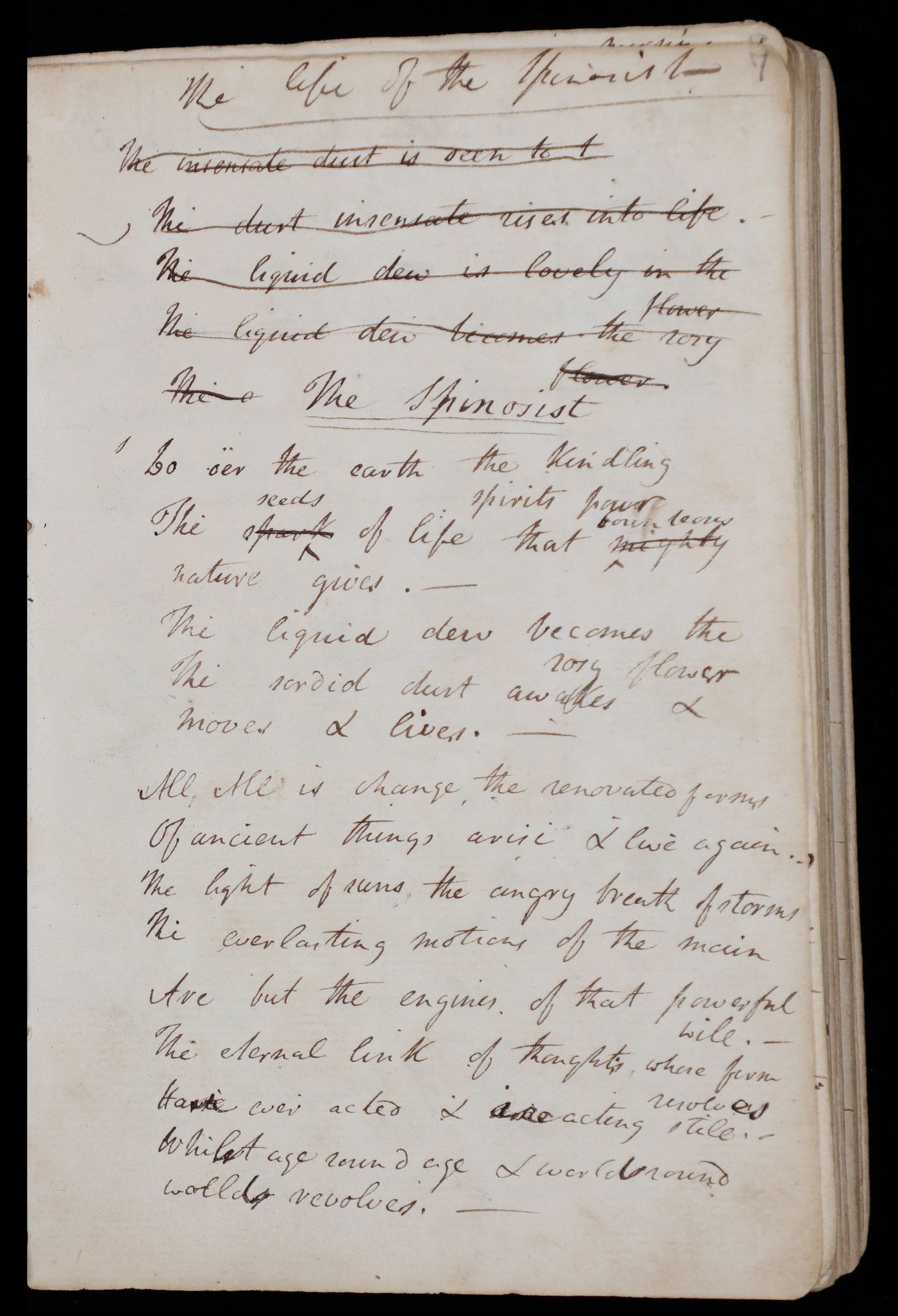

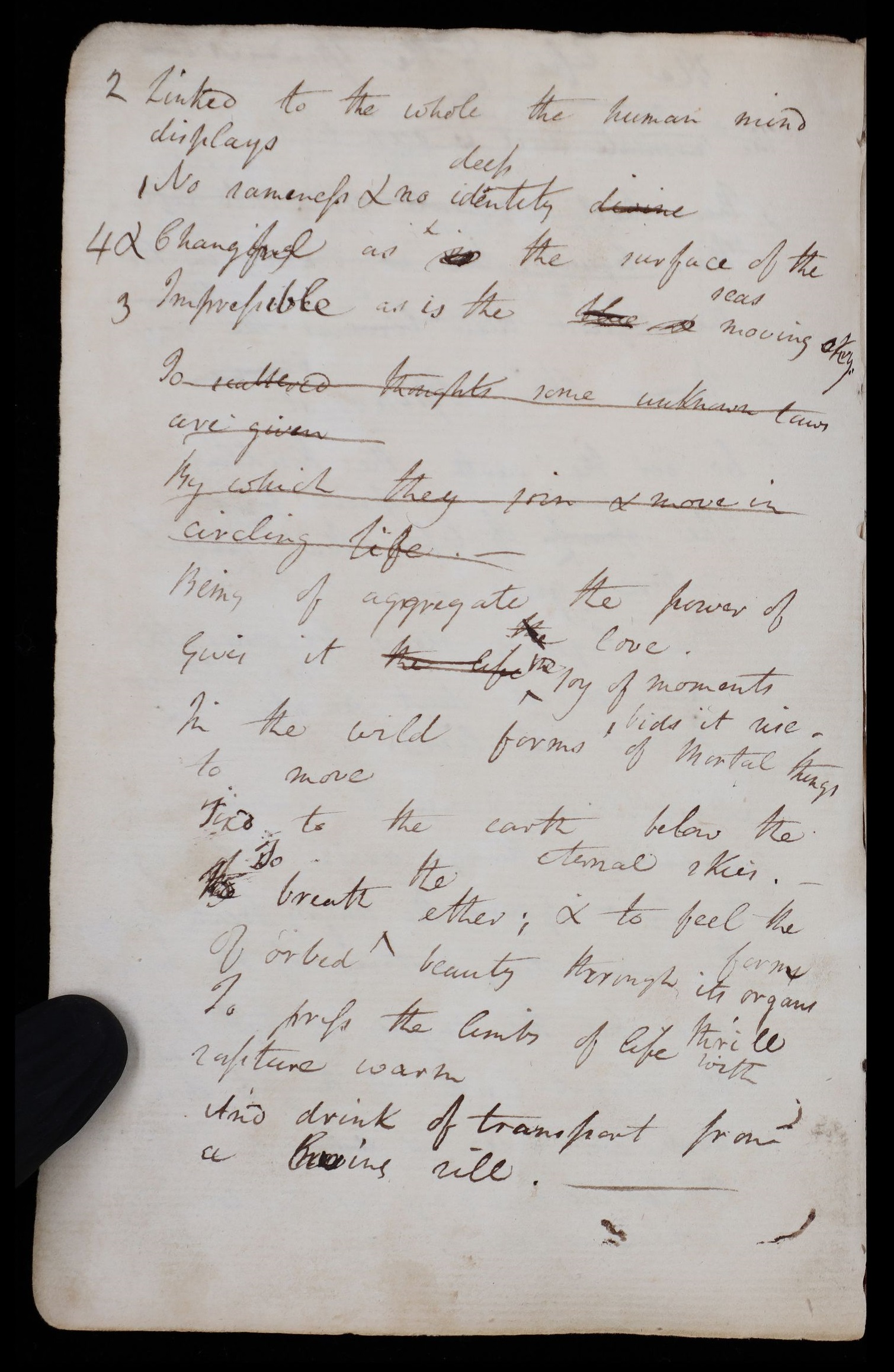

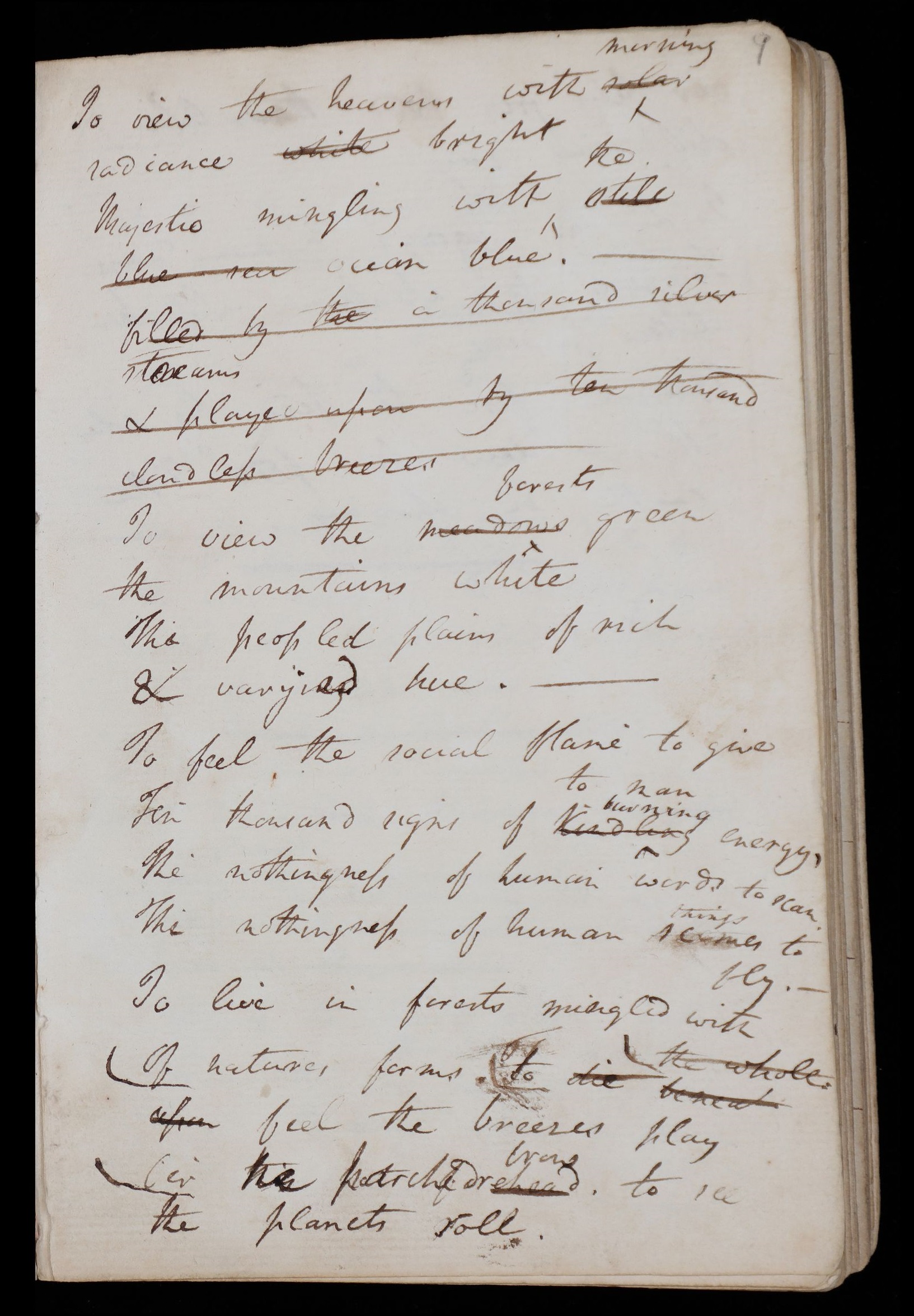

RI MS HD/13/C, pp. 7-9, ‘The Life of the Spinosist’ (click to enlarge)

Do you teach Davy?

Yes. I work at the School of English in the University of St Andrews, and I teach Davy in a class on our Romantic and Victorian Masters degree. The class uses Davy’s writings to introduce students to the broader question of the relations between literature and science in the early nineteenth century. Davy fits extremely well into the degree programme’s coverage of Romantic and Victorian literature: as well as his central importance to the history of science, he can also be studied as a representative figure in British Romanticism. His writings demonstrate this, I think, especially in their reimagining of traditional literary forms and literary language, in their championing of the social value of intellectual work, and in their examination of the links between physical nature and the spiritual or metaphysical.

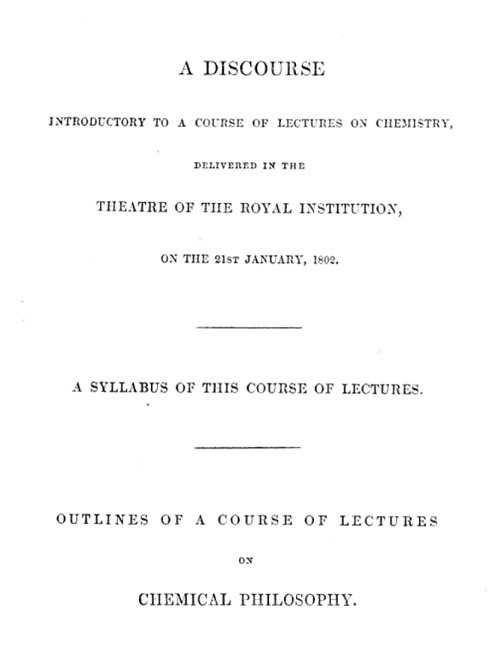

Detail from the title-page of ‘A Discourse, Introductory to a Course of Lectures on Chemistry’ reprinted in The Collected Works of Sir Humphry Davy, vol. 2 (1839)

What do you teach?

I ask students to read Davy’s 1802 ‘A Discourse, Introductory to a Course of Lectures on Chemistry’, primarily because I think it’s a model of early nineteenth-century rhetoric, and it therefore helps them to see (often for the first time) the linguistic, rhetorical, and figurative aspects of scientific knowledge. The ‘Discourse’ is an excellent text for showing students of English that they can study scientific writing through the same methods of critical analysis that they use to study literature. And it demonstrates to students that public lectures can be understood as a form of literature as well.

I also teach the different versions of the poem that started as ‘The Spinosist’ or ‘The Life of the Spinosist’ in Davy’s notebooks, before being revised and published as ‘By Mr Davy’ in 1806, and then again as ‘Life’ in 1823. Students are very interested in tracing the similarities and differences between these versions: the poem is an excellent example of the habit of lifelong revision that Davy shared with other Romantic poets. The different versions also highlight the diversity of textual forms in which Romantic poetry was written: private notebooks, periodicals, literary anthologies. And the poem also illustrates the different phases of Davy’s career and, more broadly, the intellectual and social contexts of science in nineteenth-century Britain. Each version is underpinned by a distinct philosophical framework, and the differences between them can tell us a lot about Davy’s changing views on religion, politics, and the position of science within society.

What have you published on Davy?

In 2019 I published an article on ‘Humphry Davy and the Problem of Analogy’, in a special issue of the journal Ambix edited by Frank James and Sharon Ruston. In it, I argue that analogy was central to Davy’s understanding of scientific knowledge, and that analogical thinking is a pervasive presence in his work on chemistry, his philosophical writings, and his poetry. Analogy was an essential intellectual tool for Davy, because it enabled him to construct broader theoretical conclusions from specific observations of physical processes and experimental data. But, throughout his writings, he also worries that analogical reasoning is illegitimate, both because it is arguably based on imaginative speculation rather than the rational interpretation of facts, and because it is a mode of rhetoric, the persuasiveness of which depends not on concrete evidence but on misleading figures of speech. This is ‘the problem of analogy’, which remains unresolved throughout Davy’s writings.

And in 2020 I published a book titled Nineteenth-Century Poetry and the Physical Sciences: Poetical Matter, the first chapter of which is on ‘Wordsworth, Davy, and the Forms of Nature’. The chapter’s argument is that Davy and William Wordsworth both understand the methods of Romantic poetry and science to be similarly inductive, building theoretical conclusions on the basis of observations of the material forms of nature. But their understandings of those natural forms are essentially different: in Davy’s chemistry, they are dynamic and mutable, while in Wordsworth’s poetry they are presented as permanent and unchanging in the psychological and spiritual associations they convey to the human mind. Davy’s work is foundational to the wider argument which structures the book as a whole: that, throughout the nineteenth century in Britain, science and poetry were viewed both as similar and as opposed to each other, because of their differing perspectives on the interpretation of nature’s materiality.

When did you first become interested in Davy?

I first became interested in Davy a decade ago, when I started work on my project on the relations between poetry and science in the nineteenth century. Through the work of Sharon Ruston, I learned about the large volume of poetry written in Davy’s notebooks, and so I spent several very happy months studying the notebooks in the archives of the Royal Institution.

Why are you interested in Davy?

For me, perhaps the most interesting thing about Davy is that he embodies two distinct (and arguably mutually exclusive) models of intellectual work. On the one hand, he was the prototype of a professional man of science, earning a living through his scientific research and setting out a vigorous defence of the particular value of scientific knowledge to culture and society. On the other hand, his work crosses and undermines barriers between different intellectual disciplines: he was as happy (or almost as happy) composing poems and works of speculative philosophy as he was writing scientific lectures and treatises. I’m a big fan of Jan Golinski’s 2016 book The Experimental Self, which interprets Davy’s career as a series of intellectual, methodological, and social performances, through which Davy fashioned (and then sometimes discarded) different identities or personae for himself. I find Golinski’s argument to be very persuasive, and, as a literary scholar, my main interest in Davy concerns the ways in which these various performances and identities (poet, philosopher, ‘man of science’) are constructed and conveyed in the language of his scientific and poetic writing.

What potential can you see for the digital edition of Davy’s notebooks?

My research on Davy’s notebooks at the Royal Institution was one of the most enjoyable experiences of my career so far, and I think it’s wonderful that the digitisation of his notebooks by the Davy Notebooks Project is going to make them accessible to a much larger and wider readership. There is a wealth of material in them that hasn’t yet been fully studied, and that will be of interest to researchers not just in the history of science but in English literature and other subjects too. I use the Davy Notebooks Project in my teaching, because the notebooks are an exemplary demonstration of the ways in which different intellectual disciplines intersected with each other in the nineteenth century: sometimes, poems and records of experiments sit side-by-side on the same page. And the hands-on, citizen-science aspect of the Davy Notebooks Project is useful for students too: I ask students to have a go at transcribing some of Davy’s notes, which is an excellent introduction to the study of nineteenth-century manuscripts, and to the difficulty of reading nineteenth-century handwriting!