Dr Aalia Ahmed completed her PhD at Durham University with a thesis on science and religion in the poetry of John Addington Symonds. Dr Lucia Scigliano completed her PhD at Durham University with a thesis on Percy Bysshe Shelley’s apocalypticism. They both now work as English Editors for MDPI Journals, Manchester.

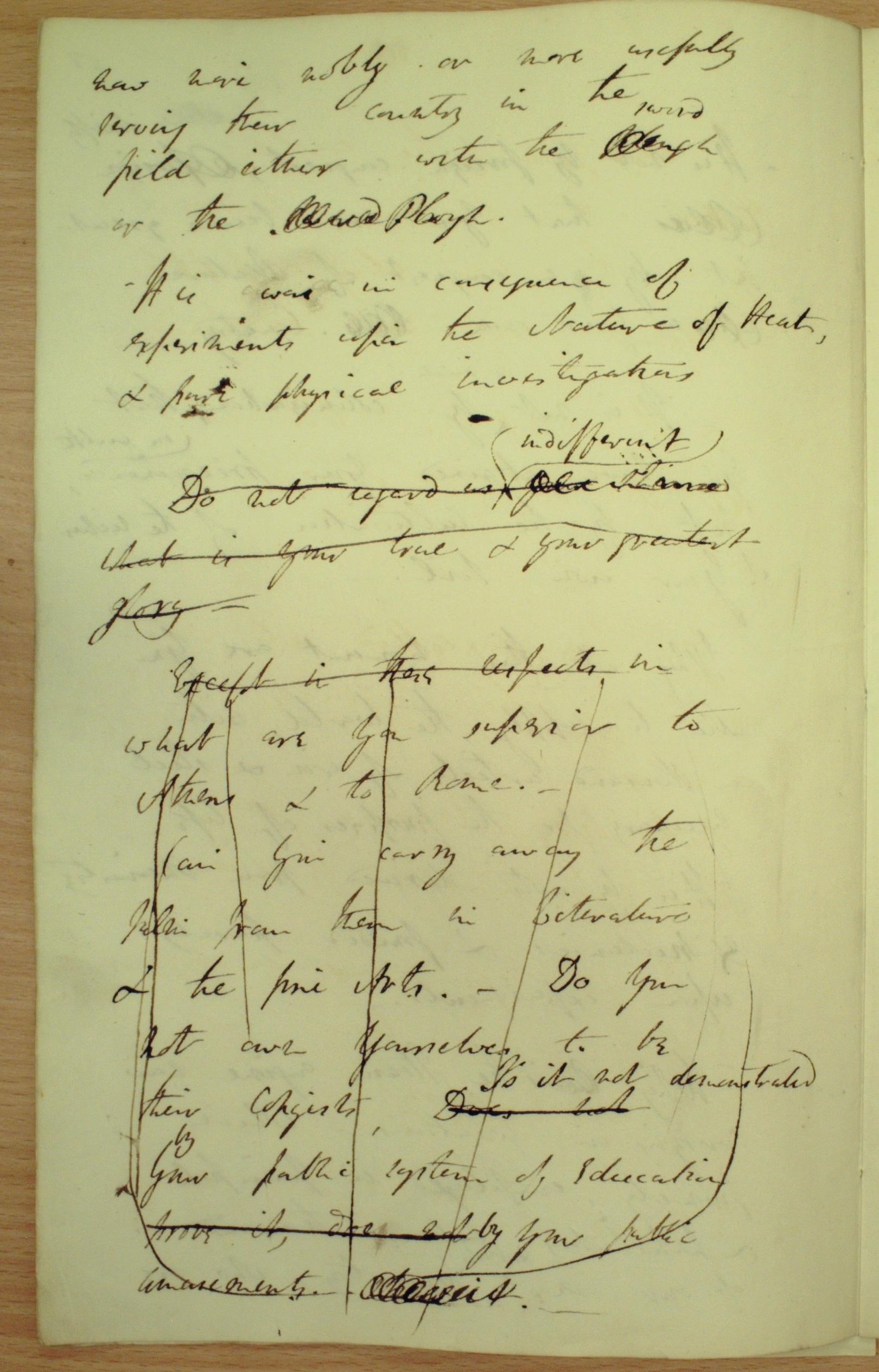

RI MS HD/03/A/1, p. 50 (click to enlarge)

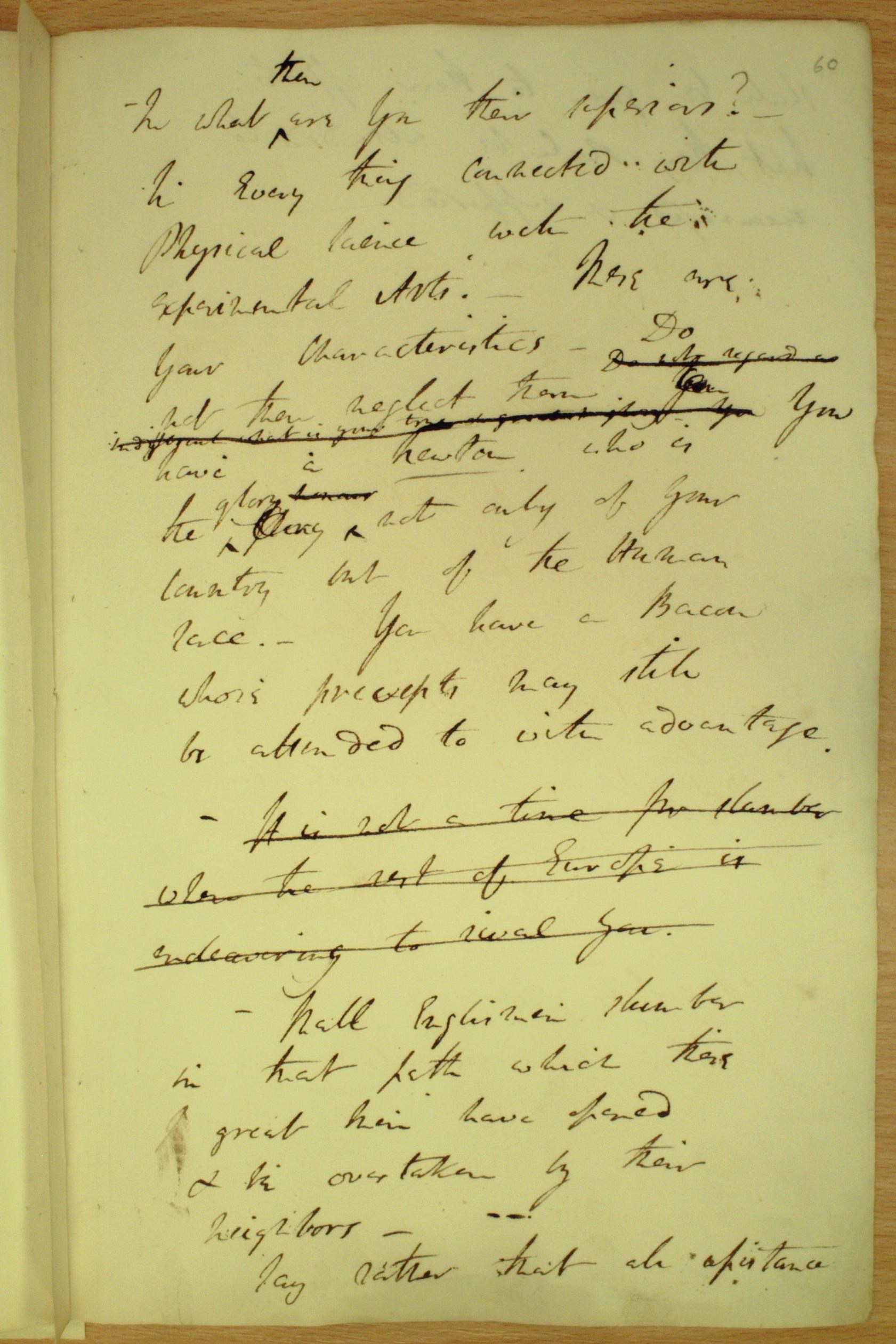

RI MS HD/03/A/1, p. 53 (click to enlarge)

On Saturday 14 May, the Davy Notebooks Project organised an in-person transcribe-a-thon event, hosted at UCL. The day began with introductory talks delivered by Professor Sharon Ruston, Professor Frank James, Dr Andrew Lacey, and Dr Eleanor Bird which contextualised Humphry Davy and the project. We learnt about Davy’s humble and radical beginnings in Cornwall and Bristol and his scientific career, specifically electro-chemistry, as the notebook (RI MS HD/03/A/1) that we transcribed during the event contained Davy’s lecture notes on this branch of chemistry, dating from 1809. The talks also focused on the materiality and preservation of the notebooks, highlighting the challenges presented by the manuscripts, such as missing or torn pages and ever-fading pencil markings, but also the benefits of this project, particularly its aim to safeguard these precious materials by their digitisation for current and future generations. We then proceeded to the transcription activity itself, which proved to be fascinating and testing in equal measure!

Facing a new manuscript for the first time, however dextrous a copyist or analyst one is, is always a challenging task that requires becoming acquainted with an author’s writing style. At first, using the tools available on Zooniverse to zoom in and out of specific words was extremely helpful, when trying to disentangle the specific letters of Davy’s scientific scribblings. Eventually, we were able to pick up on letters that to us initially appeared to be shapes and patterns, and which gradually became recognisable and identifiable as his idiosyncrasies. Davy’s double ‘s’ characters, for example, appear, to the uninitiated eye, as a ‘p’ followed by a cursive ‘s’, and the word ‘phaenomena’ takes a now obsolete spelling with ‘ae’.

The event lasted for a few hours and this gave us time to glimpse the records of ideas vital to the progress of science. In one of the pages from the notebook (RI MS HD/03/A/1, p. 50), Davy refers to ‘experiments upon the structure of Heat’, a curious concept forcing us to engage our own imagination to envision the mechanisms of energy transfer. Another page from the same notebook presents Davy’s meditations on the nature of lightning and electricity, alluding to the scientific kite experiment that he ascribes to Benjamin Franklin. However, not all of Davy’s notes are circumscribed to his reflections on the experimental sciences. Another page from the manuscript offers lecture notes reflecting on the pioneering spirit and potentiality of British science. Davy refers to Francis Bacon and his contributions to philosophy and science, as well as to Isaac Newton, whom he champions as the ‘glory’ not only of England but also the human race. Davy encourages, in these pages, the promulgation of the spirit of innovation of ‘Englishmen’, proposing that the scientific advances and discoveries achieved in the British Isles have the ability to rival those of Europe (RI MS HD/03/A/1, p. 53).

Unfortunately, we were not lucky enough this time around to encounter any of Davy’s sketches or poetry, which appear in other notebooks. Since Davy tended to synthesise the cultures of the arts and sciences, it would have been a wonderful opportunity to be able to experience an instance of this done in his own hand. This has encouraged us to continue the transcribing process on Zooniverse in the hopes of chancing upon Davy’s scientific reflections presented in the language of poetry to further understand the interconnections between the two fields in the early nineteenth century. The event also allowed us to rediscover the wonderful world of manuscripts, which is always an exciting moment in any academic’s career, but digitally, which we had not yet experienced. The ability to zoom in and out of particular sections of the manuscript, when the handwriting is difficult to decipher or sentences are crossed out to the point of illegibility, is a distinct benefit of the digitised life of the manuscript that gives us the ability to move beyond the immediacy of the physical page and understand the creative and scientific processes informing the writing of the notebooks.

Participating in the editing process of the digital version of Davy’s manuscript notebook was an extraordinary experience. For us, the fact that the project is hosted via the Zooniverse platform is a particular asset to this endeavour as it offers the possibility of widening the project’s audience beyond academia and the UK and encouraging interdisciplinarity by collecting the diverse knowledge of all the volunteers who transcribe the notebooks. This has given many people from varied walks of life the chance to participate in and contribute to such a unique project and huge enterprise. Having the opportunity to consult and transcribe these notebooks brings us face to face with the (sometimes tortuous) inception of the many phenomena that we nowadays take for granted, forcing us to realise the importance of these discoveries and the long-lasting impact that they have on our quotidian and the ways in which we conduct our lives. It encourages us to reflect on how imagined possibilities become, one day, the facts of life that govern the ways by which we understand our position in the universe, thus influencing the way we live.