Blog post by Sandra Kemp, V&A project Principal Investigator, on the AHRC/LABEX cross-project workshop on transnational interdisciplinary research.

…Connections between the many become locally denser until at some point a threshold is reached and things begin to flow.

Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics 1, 2010, 157

Last week the AHRC/LABEX brought together researchers from its eight funded Franco-British projects to discuss interdisciplinary, intersectoral and transnational research.

Both funding streams are rooted in history: LABEX’s concerns ‘Pasts in the Present’, and the AHRC ‘Care for the Future’ (CFF) theme comprises ‘Thinking Forward through the Past’. Both prioritise rethinking how the academic and heritage worlds interact, and their relations to the future. Over the course of this fourth cross-project workshop, held at the German Historical Institute in London, case studies reflected the diversity of methodologies and sources used to collect the past. Discussion centred on three core themes:

- Interdisciplinary research, its uses in “thinking forward through the past”, and how the future is altered by the ways in which we remember the past.

- Research within the museum and heritage sector – the changing role of the curator.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration in the arts, humanities, and digital and data sciences.

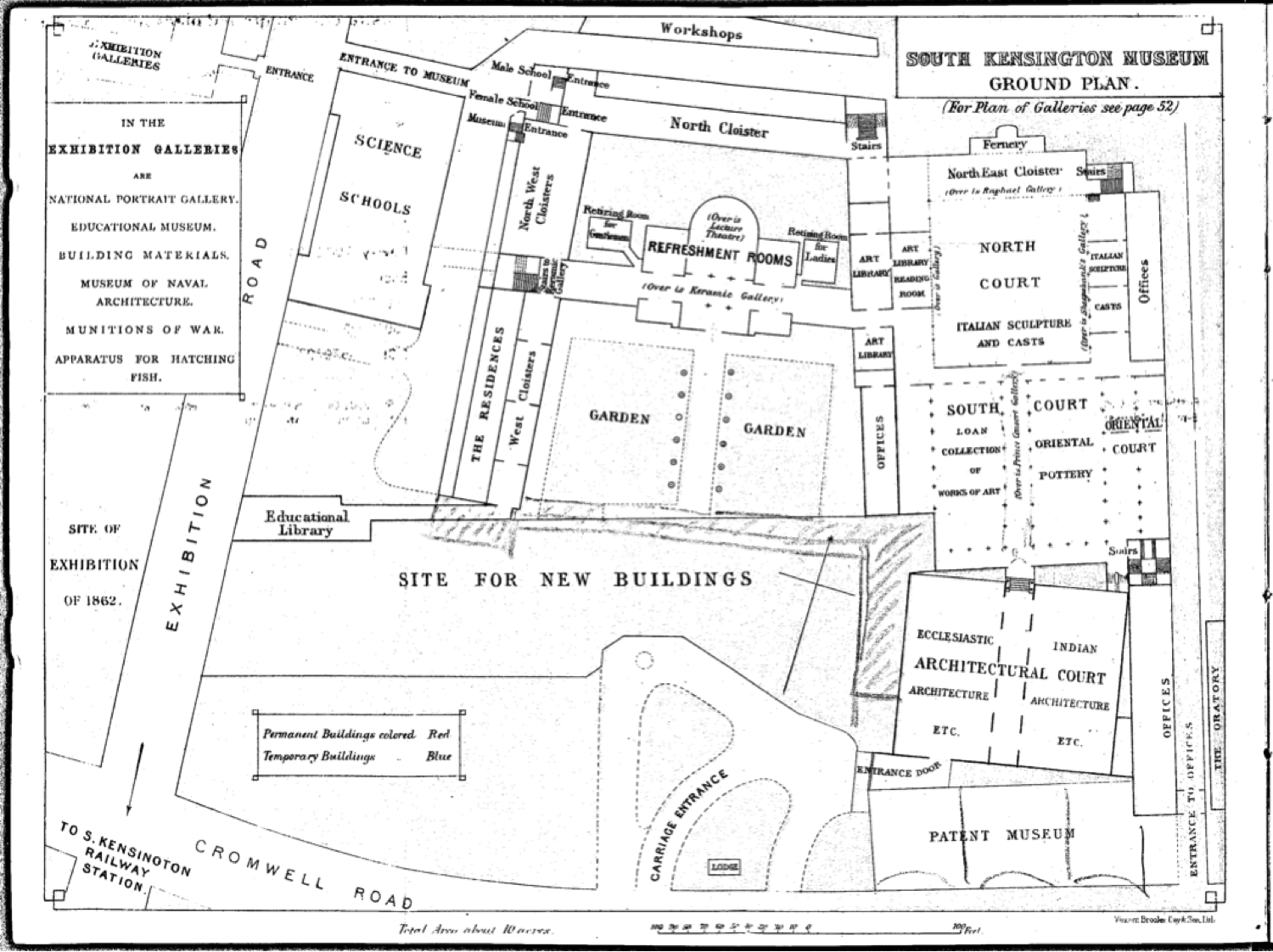

South Kensington site map, showing the South Kensington Museum, National Portrait Gallery and location of Apparatus for Hatching Fish.

For some participants, the agency of the interdisciplinary was its head-on disruptive potential; for others, as in The Criminalisation of Dictatorial Pasts in Europe and Latin America project, it came sideways through collaboration between academics and professional experts involved in reckoning with the past. These included jurists, curators, activists and organisations such as IC_MEMO, which brings together more that twenty museums dedicated to the memory of victims of political crimes.

“Story is our only boat for sailing on the river of time”, wrote the novelist Ursula Le Guin (1994), and the importance of story-telling and site biographies was highlighted by a number of workshop participants, demonstrating the different ways in which the interdisciplinary nudges new forms of thought and vocabularies.

Refraction and revision of historical and anthropological perspectives was central to several projects. The Dark Tourism research team focused on “Imperial Story-lands”, marginalised histories, and mismatches between public discourse about displaced groups and individual experience. Through comparative analysis of international penal ‘sites of suffering and of memory’, and of evictions in colonial and apartheid west Namibia, the case studies in the Dark Tourism and Disrupted Histories, Recovered Pasts projects respectively revealed the competing and multidirectional claims of memory, commerce and politics. Ethics and the social practices of interdisciplinarity were a key focus for discussion.

File ED84/154, V&A Archive.

Along with researchers from the Dark Tourism project, and the OPAL project, which brings together online numismatic collections via Linked Open Data, our Universal Histories & Universal Museums team debated the changing role of the curator as a result of collaborative research across universities and the museum and heritage sectors. All three presentations touched on:

- Exhibition-making as process as well as outcome

- Collections-based knowledge

- Digital skills

- Interdisciplinary team work

- Knowledge Exchange skills

Our own presentation explored object-led research and the curatorial role in the material shaping of knowledge in museums in four contexts: expertise, engagement, outputs and impact. Speaking as a classical historian, Hervé (Ingelbert) discussed relationships between curators/exhibitions and new fields of historical research, such as global history. This started a debate about whether and how multiple perspectives and theoretical viewpoints can be presented in exhibitions. As a former archaeologist, museum curator at the Musée du quai Branly and now Director of the Musée de l’Homme, André (Delpuech) presented some of his own curatorial projects, arguing for agility in moving amongst different specialisms by analogy with the GP.

Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.

Taking as my starting point the ambitious collecting, display and educational programmes of our 19th century case study museums in London and Paris, I outlined the work Chiara and I have been doing on curation as a powerful interdisciplinary methodological resource to reflect social, cultural and economic realities. How do we make knowledge inclusively, and how is it best translated and displayed to promote multilateral engagement? Or – as Asia Art Archive Head of Research and Programme Hammad Nasat speculates in conversation with Anna Sophie Springer and Etienne Turner, each new generation of curators unravels tangled histories from the geographical or intellectual margins and unleashes possible futures through re-evaluation. Our research has fascinating intersections with the London, Asia project, led by Sarah Victoria Turner and Hammad Nasar, which asks broader methodological questions about the ways in which the art histories have been, and are being, written, circulated, and negotiated.

The Nehru Gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Nasat’s ‘Conversation’ is published in Fantasies of the Library (2016). Unpicking the ways in which we display and archive culture and scholarship, this edited collection is about imagined critical territories which traverse disciplinary and professional boundaries. Articulated through word and image, and drawing on historical examples, political trajectories and digital futures, the essays reveal the radical contingencies of knowledge infrastructures and posit new interrelationships. They also offer alternatives for the ways in which the collaborative project is itself becoming a rigid “unit of knowledge production” in the Humanities. As Emmanuelle Grimaud put it during the workshop panel debate, the sum of the interdisciplinary parts should be more than a list of names, as, say, in a film credit. The dynamics of the interdisciplinary methods have always responded to changing social worlds, which in turn require new methods and methodologies, unforeseen and unpredictable research trajectories, and unintended consequences. Andrew Meadows, from the OPAL project, started his presentation by referring to article entitled ‘The Usefulness of Useless Knowledge’, first published in Harpers in 1939. This article argues for the likelihood of ‘useless’ knowledge becoming ‘useful’ later, citing for example:

The whole calculus of probability was discovered by mathematicians whose real interest was the rationalisation of gambling. It failed of the practice purpose at which they aimed, but it has furnished a scientific basis for all types of insurance, and vast stretches of nineteenth century physics are based on it.

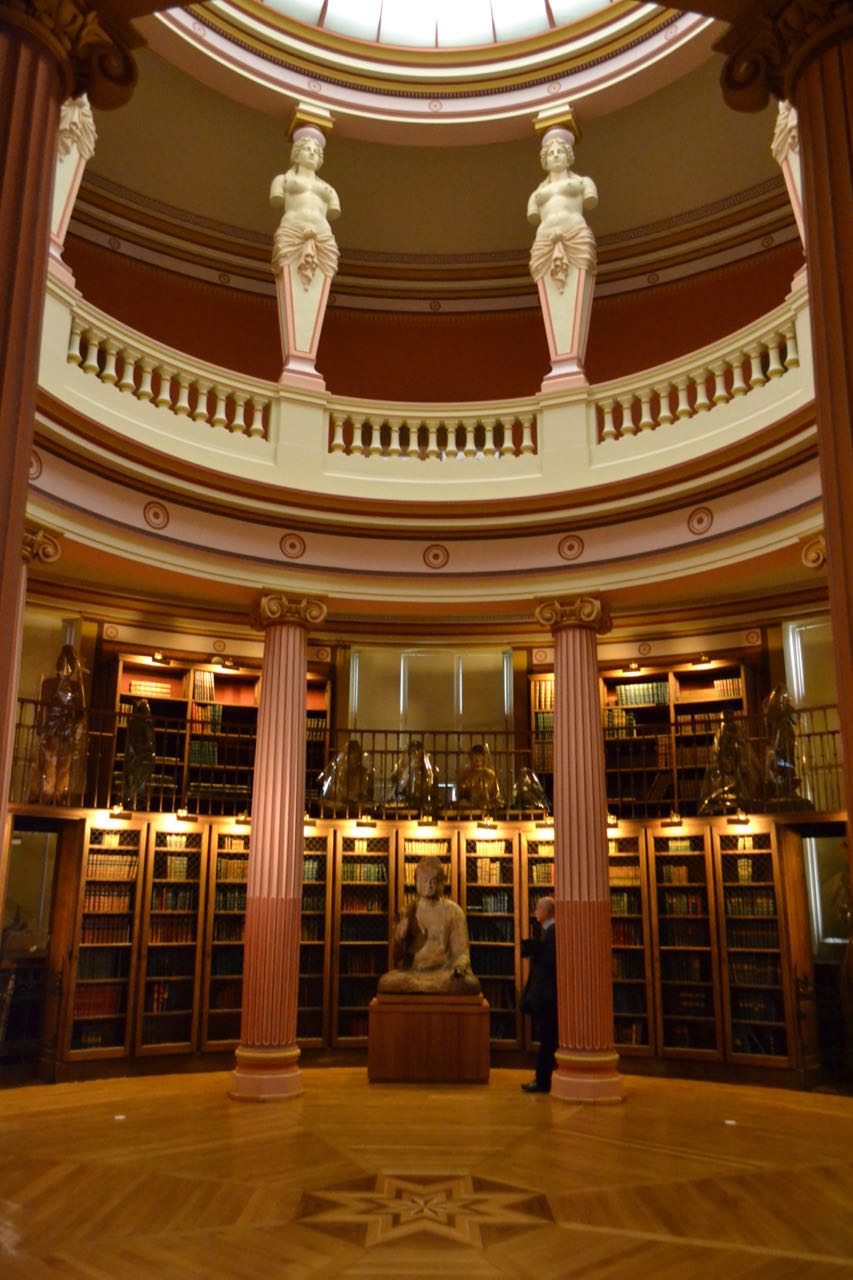

Casts Court, V&A.

For me, one of the most thought-provoking debates of the CFF/LABEX workshop centred on whether core disciplines or core themes – like time, or memory – were the most effective starting point for interdisciplinarity. In light of the many processes by which time and history are materialised in museum display, museology has much to contribute to the theorisation and application of ideas of time and temporality across all sectors and disciplines. This kind of knowledge practice is arguably just as important as an individual subject discipline. At the same time, however, in areas where the interdisciplinary has already become a form of knowledge base – as for example, in fields such as memory studies, the medical humanities or zoo archaeology – I wonder if the institutionalisation – or as one participant put it, the normalisation – of the interdisciplinary constrains its potential as a kind of third space? The Data Science for the study of calypso rhythm through history project demonstrated how interdisciplinary work involving music, computer science and ethnomusicology that had not been anticipated at the start of the research had led to new developments and dynamics in a performance of ‘Machine folk’ music composed by AI, immediately after the workshop.

Making the Modern World Gallery, Science Museum.

The integrality, interdependence and interdisciplinarity of the research methods, conventions and debates embodied in an artefact of this kind is beautifully articulated by RCA m.Phil painting student Jocelyn Cammack in the 2007 degree show catalogue (p.24): “The writing is not an analysis of post-rationalised explanation of the work, but an integral part of the exploration and generation of ideas, a way of playing with these ideas in a different modality.” Ideas of translation and performance – approached as a mode of thinking – resonated throughout our discussions. Clare Finburgh and Carl Lavery, from the Reviewing Spectacle project, cited the provocative double entrendre, courtesy of Situationist Guy Debord (1957), that the past had ‘served its time’; along with material from philosophy and the philosophy of science, including that by Isabelle Stengers and Michel Serres.

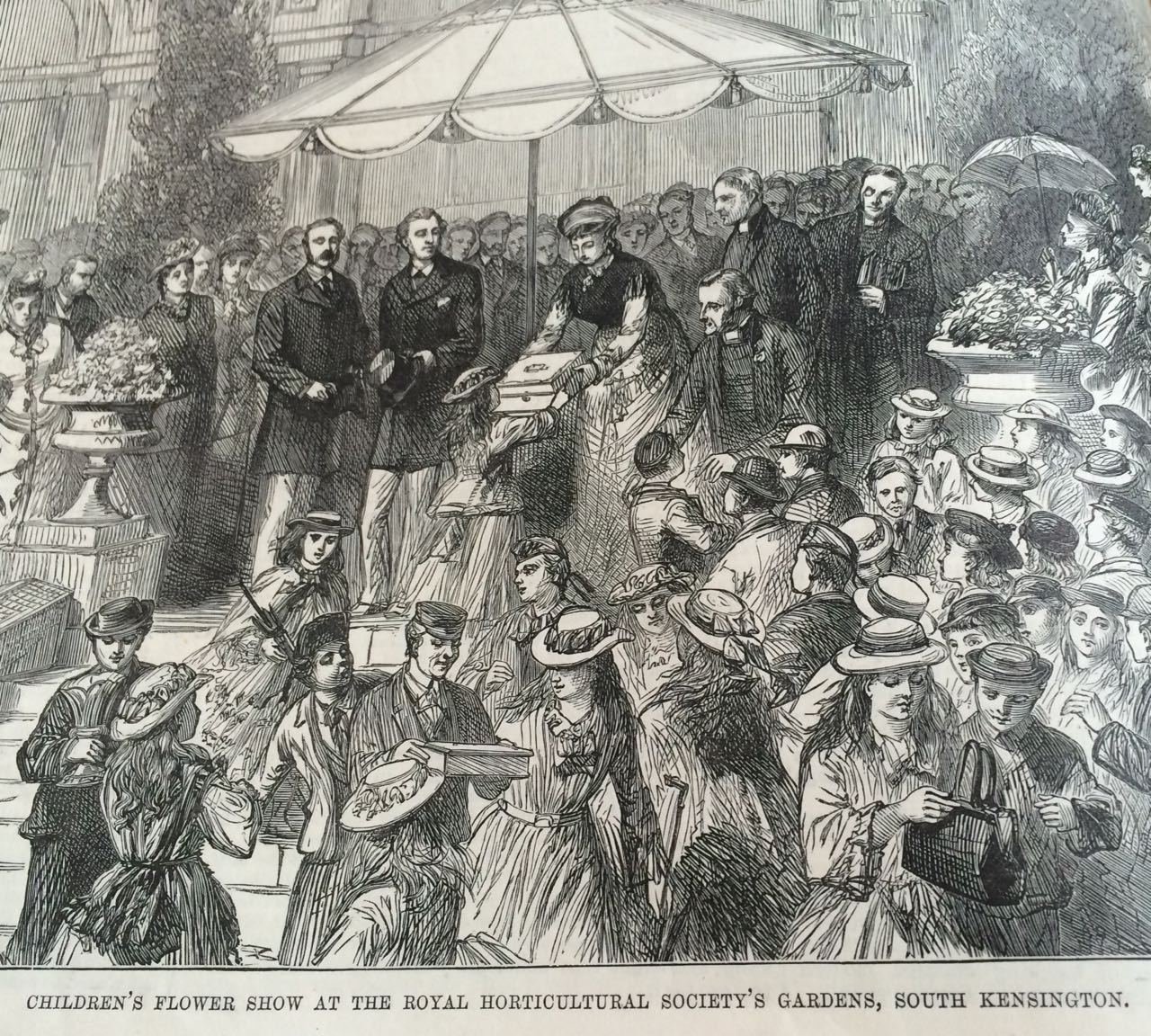

Source: Illustrated London News, 1876.

Likewise, a passing comment about how many historians across the AHRC/LABEX projects did not have a background in history, and were not based in history departments, led to discussion about specialists versus generalists, Victorians versus modern cultures of knowledge, overspecialisation, and the kinds of history we want or need today.

Returning for a moment to the practices of librarianship, current questions about the extent to which knowledge is created from the archive or by the archive reflect a similar dispersal of expertise between qualified librarians and ‘information’ professionals, and between librarians, scholars and poets. As Sarah Wingate Gray points out in a fascinating article entitled “Locating librarianship’s identity in its historical roots of professional philosophies: towards a radical new identity for librarians of today (and tomorrow):

… it is clear from many accounts relating to the Library of Alexandria that those enjoined directly in performing its services were not only primary scholars – learned as grammarians or historians, for example – but that many were also poets. Zenodotus (an epic poet and grammarian and Lycophron (included as one of the seven ‘tragic poets’, know are the Alexandrian Pleias) are such examples… The eye and ear of the modern poet too, can be discerned in more modern day librarianship incarnations – the poetry of librarians Philip Larkin and Elizabeth Jennings being two more famous twentieth century examples. (p.38)

Musée national des arts asiatiques (Musée Guimet), Paris.

A closing panel agreed that interdisciplinary working in this way takes time, especially in transnational research groups. Nor had it all been plain sailing to-date: one project reported on the less than enthusiastic public response to one of its more radical form of interdisciplinary engagement: “the sooner this work is confined to an anonymous university archive the better.”

However, when asked what more the research funders could do to support our projects, we were in agreement: more funding, more time and a unanimous thumbs-up for the Slow Professor movement!