Shakespeare and Social Status

Senior Research Associate, Dr Sean Murphy, discusses how he categorised each of Shakespeare’s 1,402 characters according to social status.

Sir Thomas Smith De Repvblica Anglorvm (1583)

Introduction

Social class matters. Sir Thomas Smith, writing at the time Shakespeare was born, was certainly attuned to such classifications, dividing men [sic] into foure sortes: Gentlemen, Citizens, yeoman artificers and labourers (note the use of capitalization). Given that the population of England grew from just over 3 million to just over 4 million during Elizabeth I’s reign, and estimates for the number of gentry vary from 15,000 to 20,000, then we can safely assume that the vast majority of the population belonged to ranks below the gentry.

Then, as now, social order was not a simple matter. People could rise in status, as does La Pucelle (aka Joan of Arc) in Henry VI Part 1, transforming herself from a shepherd’s daughter into the champion and saviour of France. They could also fall in status, like the eponymous protagonist of Timon of Athens, who goes from being a wealthy nobleman to a misanthropic hermit. Others might have been unaware of their true social status. In Cymbeline, cave-dwellers Polydore and Cadwal turn out to be the King’s sons, Guiderius and Aviragus.

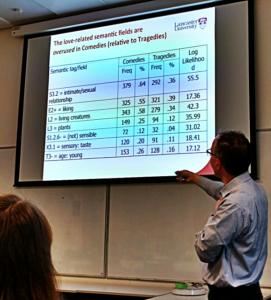

Why is social status relevant to the Encyclopaedia of Shakespeare’s Language?

One of the aims of our project is to conduct social analysis of the language of the plays. That means looking at variables such as gender and social status to see what effect, if any, they have on the language characters use. In doing so, we will be able to answer questions such as ‘Is the word ‘forswear’ more commonly used by higher or lower status characters?’; ‘Is Shylock’s language different from that of his social betters?’; and ‘What sort of language is used by servants?’. To do this, we need to add social annotation to our corpus. Put simply, this means adding information about gender and social status for each character. Such a system has not, until now, been systematically applied to Shakespeare, but the methodology has been applied to Early Modern texts (see Archer, et al. 2003).

What are the social categories and how do you assign them to characters?

Our project team devised a classification system of nine social groups. Our system is largely based on a scheme used in a study by Archer, et al. This consists of six groups (Nobility, Gentry, Professional, Middling, Commoners, Lowest), derived from historical accounts of social hierarchy. Figure 1 (below) shows our expanded version of this categorisation, including categories for Monarchy, Supernatural and Problematic, together with prototypical character examples for each group.

Figure 1: Social groups in Shakespeare and prototypical characters in each group

Monarchy merits a separate social status on the basis that, in Renaissance social theory, only God was superior to the sovereign; everyone else was a subject of the Queen or King (Innes, 2007). The Supernatural category was necessary to cover in excess of 40 ghosts, gods, fairies, etc. in the plays, as was the Problematic grouping for characters whose status was uncertain at the time, e.g. actors, or characters who undergo a significant change in status during the play, such as those mentioned in the introduction.

As regards assigning status (indicated by a number from 0 to 7, or ‘p’ for problematic’) to individual characters, in many cases, titles were clear indicators: Queen (0), Duke (1), etc. In the absence of such a title, I consulted the Arden Shakespeare list of Dramatis Personae for each play to glean as much information about the character as I could. I was also greatly aided by specialist Shakespeare dictionaries and other academic sources listed in the References section at the end of this post. These helped me to gain a sense of the relative social position of a herald (3), a marshal (2), a beadle (5), and many others, as seen through the eyes of Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Most importantly, I am fortunate in that we have Shakespeare scholar Professor Alison Findlay on our team. Alison provided expert advice and many invaluable insights as to the social status of individual characters.

How many characters are there in each social group?

Figure 2 (below) shows the numbers of characters per social group. The largest group is that of the Nobility (379 / 27% of all characters), closely followed by the lowest social group (324 / 23.1%). Together with the Gentry (263 / 18.8%), these three groups account for nearly 70% of all the characters in Shakespeare’s plays. The remaining categories account for between 3 to 7% of characters each. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the higher social ranks are vastly over-represented compared to the actual population in Shakespeare’s day (see Introduction), whilst the middling and lower orders are perhaps under-represented. Then, as now, drama often concerned itself with the high and mighty – What great ones do the less will prattle of, says the Captain in Twelfth Night. That said, perhaps Shakespeare’s enduring popularity can partly be accounted for by the relative prominence of characters from the lower social orders.

Figure 2: Number of characters per social group

How do social groups compare across genres?

A number of interesting findings emerge by comparing social categories across genres (see Figure 3). First, the nobility are proportionally best represented in histories. This is probably because historical drama largely concerns itself with factions made up of nobles belonging, for example, to the Houses of York and Lancaster, competing for supremacy. Comedies, by contrast, show higher proportions of gentry, professional ranks and commoners. The characters in comedies are perhaps easy for audiences to relate to, and closer to everyday life than those in histories and tragedies. Tragedies, and to a lesser extent, histories, contain higher proportions of characters belonging to the lowest social groups – servants, messengers, soldiers, etc. This may be due to their requirement for the plot to function (messengers are a good example), or to provide a change of mood (e.g. the Porter in Macbeth).

Figure 3: Percentage of characters per social group by genre

What problems did you encounter?

Although assigning gender to characters is generally a straightforward task, it becomes more complicated when characters assume a disguise. We identified 36 such cases in the plays, mostly in comedies and tragedies (well-known examples include Viola as Cesario in Twelfth Night, or Edgar as Poor Tom in King Lear), with only one instance in histories, when Henry V disguises himself as a common soldier on the eve of the battle of Agincourt. Assumed identities often imply a change in social status, and sometimes gender. In As You Like It, Rosalind as herself is female and the daughter of a Duke (status 1); in her disguise as Ganymede, she is male and a shepherd (status 5). The fact that all women’s parts were played by boys in Shakespeare’s day was fortunately not a consideration I had to deal with in assigning gender to characters.

The Roman plays also presented a challenge in terms of comparing Early Modern social status with that of Ancient Rome. Nevertheless, Elizabethan audiences must have recognised and understood social hierarchies in the Roman plays. Careful consultation of sources cited in the References allowed us to map categories to status in the following manner: nobility – aristocrat, patrician, nobleman, triumvir; gentry – consul, senator, general; professional – praetor; other middling groups – tribune, aedile; ordinary commoners – citizen, plebeian.

A third problem we faced was in assigning social status to characters who did not easily fit into one of our categories. We identified over 50 such problematic cases, including speakers of prologues and epilogues, soothsayers, actors, musicians, poets and characters who undergo a radical change in status over the course of the play, Timon of Athens being a good example (wealthy nobleman to hermit).

What further applications might this classification have?

Project team member Jane Demmen has already applied the same classification to the characters in our corpus of plays written by contemporaries of Shakespeare (Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, John Fletcher, etc.). This will allow us to compare how Shakespeare’s linguistic representation of different social ranks compares with that of his fellow dramatists. Given that dramatic texts are probably the closest we can get to authentic speech in the Elizabethan and Jacobean period, linguistic analysis based on social stratification may provide insights into how those Gentlemen, Citizens, yeoman artificers and labourers actually spoke.

References

Amussen, S. (1988). An ordered society: Gender and class in early modern England (Family, sexuality, and social relations in past times). Oxford, UK ; New York, NY, USA: B. Blackwell.

Archer, D., Culpeper, Jonathan, Wilson, A., Rayson, P., & McEnery, A. M. (2003). Sociopragmatic Annotation: New Directions and Possibilities in Historical Corpus Linguistics.

Berry, R. (1988). Shakespeare and social class. Atlantic Heights, NJ: Humanities Press International, Inc.

Edelman, C. (2001). Shakespeare’s Military Language. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Hassel Jr, R. C. (2015). Shakespeare’s religious language: a dictionary. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Innes, P (2007) Class and society in Shakespeare: A dictionary. London: Continuum.

Smith, T (1583), De Repvblica Anglorvm: The Maner of Gouernement or Policie of the Realme of England. London: Printed by Henrie Midleton for Gregorie Seton.

Luke Wilding:

Luke Wilding: Isolde Van Dorst

Isolde Van Dorst Becky Hoddinott

Becky Hoddinott