By Nicola Spurling

In our recent Mobile Utopias 1851-2051 workshop one of the topics that came up was ‘what would happen to all the parking space in cities, if there were no more cars?’ (see blogpost by Georgia Newmarch, 24th April 2016). A related question, is through what processes might parking space in our cities, towns and residential areas be un-made. To help with that question, my recent historical work in Stevenage new town (part of the DEMAND centre research programme) looked at how parking space became a normal part of the infrastructure in the first place. What was parking space for before it was allocated to the car? How did parking space come to be prioritised? How did it become a legitimate, planned for, and normal aspect of everyday life?

In 2014 there were 28 million private cars in Great Britain. If every car has a space at its owner’s home, that’s 336 million meters square. Nearly all the Isle of Wight, or placed in a straight line, a third of the distance to the moon. It is certainly the case that parking space is a big topic. At the same time it’s almost entirely absent from discussions of how automobility became embedded into everyday life. My work argues that parking space played a critical part in making automobility what it is today. As such, it likely has a part to play unmaking automobility too.

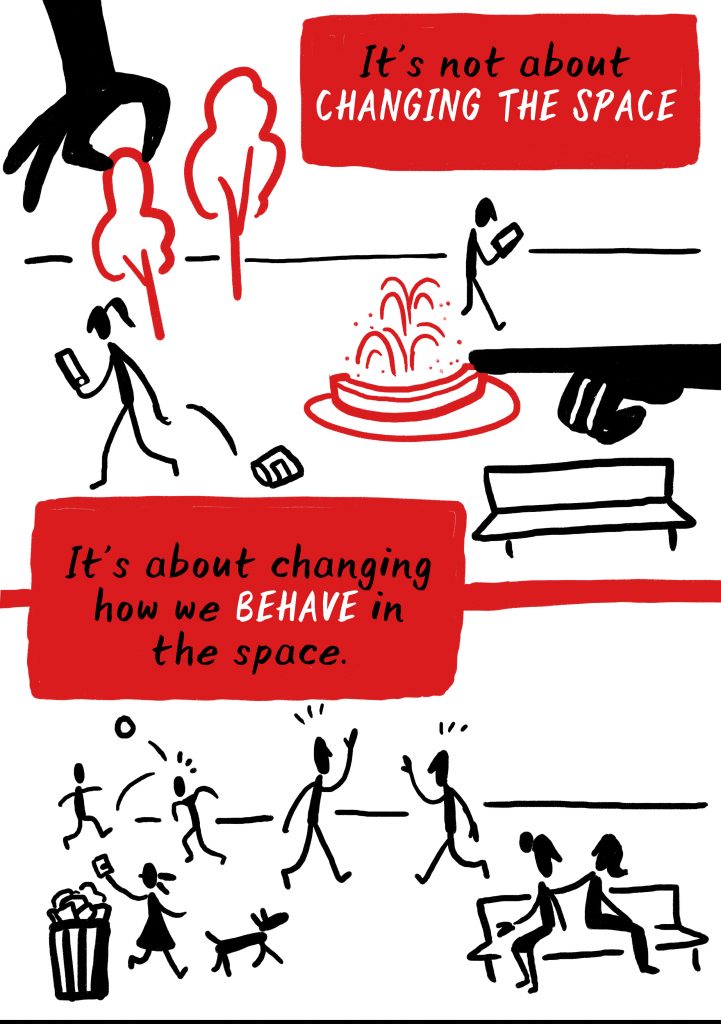

The critical role of parking space in making and unmaking automobility stems from the fact that parking spaces and car parking are at the interface of infrastructure and everyday life. On the one hand, parking space is part of the infrastructure. It represents planners’ best estimates of where destinations will be, and forms the nodes of the road network. On the other hand, parked cars are part of a living system of practice. They signify the destinations, the places, of social practices that have in one way or another become dependent upon the car. The relationship between infrastructure and everyday life is not one way, rather across time they iteratively make and shape one another. In this way parking space played a part in making automobility what it is today, for example, it helped to give automobility its characteristic convenience and partly shaped what driving and cars can be used for.

In my research I focus specifically on residential parking space, and explore how having a parking space as close to the home as possible became taken-for-granted. Stevenage New Town provides a very relevant case. It was planned in the mid-1940s and built between 1949 and 1970, to rehouse people from the slums and bomb damaged areas of London. This time period entirely coincides with the rise of the motorcar in Britain, from 1.7 million cars in 1945 to 10 million in 1970. The original plans envisioned a new way of life –a good life – for the post war working class of green garden cities and fresh country air in which all families would have their own home, a job and time to engage in leisure activities, all of which would be provided for in the town itself.

In my research I focus specifically on residential parking space, and explore how having a parking space as close to the home as possible became taken-for-granted. Stevenage New Town provides a very relevant case. It was planned in the mid-1940s and built between 1949 and 1970, to rehouse people from the slums and bomb damaged areas of London. This time period entirely coincides with the rise of the motorcar in Britain, from 1.7 million cars in 1945 to 10 million in 1970. The original plans envisioned a new way of life –a good life – for the post war working class of green garden cities and fresh country air in which all families would have their own home, a job and time to engage in leisure activities, all of which would be provided for in the town itself.

In some ways the motorcar is prevalent in the plans, for example the town was built with fast moving roadways segregated from pedestrian and cycle traffic, and the town centre was designed to be one of the first in the country to adequately provide for the motorcar.

However, the everyday lives of the skilled and semi-skilled working classes, who were to be the main inhabitants, were based on velomobility. A segregated cycleway system, land use planning and homes designed to accommodate cycles, reflect the kind of thought that went into these envisioned everyday lives. As such the initial neighbourhoods provided very few parking spaces for cars – just 1 space to every 8 houses.

My research shows that the relationship of planners to this living system of practice changed across the period of study, from the initial period of envisioning in the later 1940s there is a shift in the mid 1950s to enforcement, in the later 1950s to survey and provide, and to predict and provide throughout the 1960s. Through iterative processes of surveying, retrofitting, predicting and planning for the future, planners’ methods moved way from a focus on whole ways of life and the kinds of mobility and space such ways of life would need, to ever greater provision for the car. In relation to parked cars, many other forms of space – front and rear gardens, landscaped areas, children’s play areas and allotments – were lost along the way.

Based in the Institute for Social Futures at Lancaster, I am now developing this historical work to think forward to the future. To start with, this is in the form of desk-based work to develop three scenarios all based around the central idea that parking space is an interface of infrastructure and practice. My aim is to develop this into a collaborative project with planners in local authorities and private practice.

In the first scenario I am looking at the current parking strategies of local authorities. Here the focus is on what futures of car dependence parking strategies anticipate. For example town centre regeneration often places car access and parking as central. In fact, in many cases it seems that the idea of regeneration has itself become car dependent. An alternative approach would be to envision the town centre of the future (e.g. recent studies of changes in shopping habits and the shift to online shopping would be a start), and the associated mobilities – and thus interfaces – of that future vision.

In the second scenario I focus on the importance of parking spaces for supporting and making any transport system possible – in particular those based on private vehicle ownership. If we accept that parking space was vital in making automobility, then likewise it is vital for other systems – of velomobility, of electric bicycles, of electric vehicles and so on. Rachel Aldred and Kat Jungnickel’s work in 2013 has already looked at the problems and challenges of parking bicycles destinations in London, including at home. How does a focus on interfaces help us better design these substitutes for automobility?

Peaks, Sites and Cycles: at Utrecht Station, the Netherlands, the only parking spaces available in the morning peak are on the third floor of the Cycle Store. Photo by N Spurling

In the third scenario I am focussing on alternatives to private vehicle ownership, and the kinds of interfaces that such alternatives might demand and produce. At the moment I’m looking at driverless cars and uber, though of course many other alternatives exist that we might learn from including trams, buses, trains and city bike schemes. Such systems entirely change the kinds of interfaces between infrastructure and everyday life that we need, as well as ultimately freeing up much of the hard standing space in cities and suburbs. This takes us back to the question with which we began: if we can make the utopian vision of a future with much less automobility a reality, then what might all that space become?

I would really like to hear from potential collaborators to develop these future scenarios with me. Especially from planners in local authorities and the private sector. Collaborating could just be an email exchange, responding to this blog, a short meeting, a lunchtime or half day workshop etc. Please get in touch n.spurling@lancaster.ac.uk