Thrills, spills, shocks and howlers. Heart-stopping moments that united nations. More own goals than you can shake a stick at.

This month sees the well-awaited return of the UEFA European Football Championship (commonly referred to as the ‘Euros’) after its postponement in 2020. Despite the restrictions still in place, millions across the UK and the world have taken to various stadiums and pubs to cheer for their team.

We’re at the business end of Euro 2020 and wonders will never cease – England have seen off the auld enemies and are in the mix.

Don’t despair if you can’t tell a panenka from a peptide, distinguish Ronaldo from Röntgen or if you think tiki-taka is a minty sweet. Our GISMO Galacticos have chosen their soccer science worldies which have taken the beautiful game to a whole new level.

The maintenance of football turf is serious business. Image: Josiah Day via Unsplash.

Pitch perfect

Grass is still the normal surface of play during a football game, and there is a surprising amount of science behind the upkeep of the pitch.

The UK has been described as the ‘Silicon Valley of turf’, with the English grounds-management sector employing over 27,000 people alone. Specialists include those who breed grasses that grow in the shade, to scientists who develop chemicals to make grass appear greener.

The Sports Turf Research Institute in West Yorkshire studies everything from how quickly water passes through different types of sand to how the fineness of a stem of grass influences the roll of a golf ball. In Warwickshire, Bernhard and Company are responsible for the world’s best sharpening systems for mower blades, whilst Allett in Staffordshire provides elite mowing and maintenance equipment.[1]

Artificial turf is sometimes used in locations where maintenance of grass is more difficult due to the weather, whether it be areas where it is very wet, causing the grass to deteriorate rapidly; where it is very dry, causing the grass to die; and areas where there is a lot of snow in the winter months. New technology allows artificial grass surfaces to use rubber crumbs, as opposed to the previous system of sand infill.[2]

Some clubs use a hybrid of artificial and real grass. Pride Park Stadium in Derby uses a mix of 97% grass and 3% artificial turf. SIS Pitches UK who installed the artificial fibres, uses a giant laser-guided sewing machine on tracks to weave the polyethylene yarn into the ground. The natural grass grows around the fibres, anchoring it and holding the roots together, stopping the root zone from becoming displaced and allowing the pitch to recover faster.

Regardless, all modern football pitches are designed to cope with a high quantity of water in a short period of time. They use sand or gravel root zones to increase the drain rate.[3]

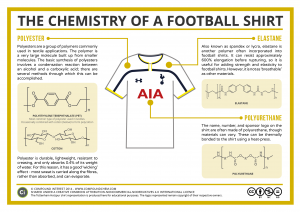

The chemistry of a football shirt. Credit: Compound Interest.

Quality kit

Modern football kits are designed to prevent any issues during the game. They are water resistant, breathable, tough and lightweight. In the past football shirts were made from cotton or wool which had the obvious disadvantage of being warm, heavy, and absorbed water and sweat.[4]

Compared to 50 years ago, there is considerably less material used to produce a football kit today. The highly-engineered polyester mesh is stronger and more lightweight than any naturally occurring fibres. The hydrophobic polymer fibres move water and sweat away from the skin via capillary action, pulling water away from the body quickly and dispersing it across the outer surface of the shirt.[5]

The 2014 Fifa World Cup kits designed by Puma combined athletic taping and compression fit fabric within the kits, placed strategically to provide micro-massage to the player to specific muscle areas, which helps promote energy supply to the muscles. The technology, known as ACTV, helps to reduce the muscle vibration in athletes. The gradual compression promotes stamina recovery, which in a 90-minute game could make the difference between winning and losing.[6]

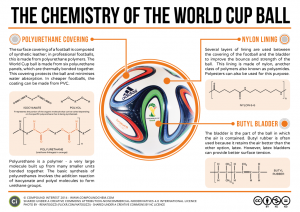

Chemistry of the World Cup football. Credit: Compound Interest.

Ball or nothing

The first footballs were made from natural materials, such as an inflated pig bladder inside a leather cover. Today, footballs consist of three

main components: the outermost layer, the lining, and the bladder, all made from artificial materials.

The outer layer of the ball is made of six polyurethane (a type of polymer) panels thermally bonded together, which protects the ball, prevents it from absorbing water, and makes it more lightweight than the leather used in the past. Polyurethanes are made up of compounds called isocyantes and polyols – the middle parts of these molecules can be varied to create varying properties. Polyurethanes have a wide range of applications, including foam, adhesives, synthetic fibres and even skateboard wheels.

The lining underneath the outer later improves the ball’s bounce and strength and is often made of nylon. Nylon is also often in the manufacture of football shirts, as well as other clothing, food packaging, resins, and filaments. Nylon polymers can be mixed with a wide variety of additives to achieve many different property variations and can be highly resistant to heat, weathering and abrasion.

Finally, the innermost part of a football, the bladder, is the part that holds the air. In the World Cup 2014 football this is made from butyl rubber, which retains the air for a longer period of time, but often latex is also used, which provides better surface tension.[7]

Antonio Rüdiger wearing his custom 3D printed face mask. Image: Evening Standard.

Face value

During Tuesday’s match, you may have noticed Germany’s Antonio Rüdiger wearing a mask on his face. Rüdiger suffered from a facial injury during last season, described as ‘a little bone injury on the side of the face’.

The mask was created by Cavendish Imaging using 3D printing. Their software scans every detail of a player’s facial features and a customised mask is printed. The masks are padded with soft material and are made from carbon fibres, a material as strong as steel but weighing just 65 grams.[8]

Back-of-the-net business support

Regardless of England’s outcome this year, there will be no penalties from working with GISMO. We can help you and your business make the most out of your current techniques, help you to develop prototypes and new designs, and make your products and processes more greener and cost effective – at no extra cost.

Get in touch now, and we’ll start you off with a materials MoT with our experts to explore your needs.

GISMO is part-funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

1. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2021/jun/15/silicon-valley-of-turf-uk-perfect-football-pitch

2. https://football-technology.fifa.com/en/standards/football-turf/

3. https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2016/10/hybrid-football-pitches-why-the-grass-is-always-greener/

4. https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/08/14/the-chemistry-of-a-football-shirt/

5. https://www.footy.com/blog/shirts/the-science-behind-a-football-shirt

6. https://gadgets.ndtv.com/science/features/the-science-behind-fifa-world-cups-football-jerseys-535694

7. https://www.compoundchem.com/2014/06/12/the-chemistry-of-the-world-cup-football/

8. https://www.3dnatives.com/en/3d-printing-and-football180620184/#