As the Davy Notebooks Project comes to an end, and we collect, edit, and annotate the final transcriptions ready for our digital edition on Lancaster Digital Collections, the project team have been reflecting on what makes Davy’s notebook collection so special. Sharon’s recent article published in The Observer (with a shorter version on The Guardian website) discusses the reams of poetry that have been discovered in Davy’s notebooks alongside ground-breaking chemical experiments and discoveries. It is unusual to have such a large cache of notebooks, as Davy’s notebook collection held in the Royal Institution and Kresen Kernow represents, and, in this post, we’ll explore a range of different types of notebooks, including lab notebooks, their provenance, and decisions around their cataloguing.

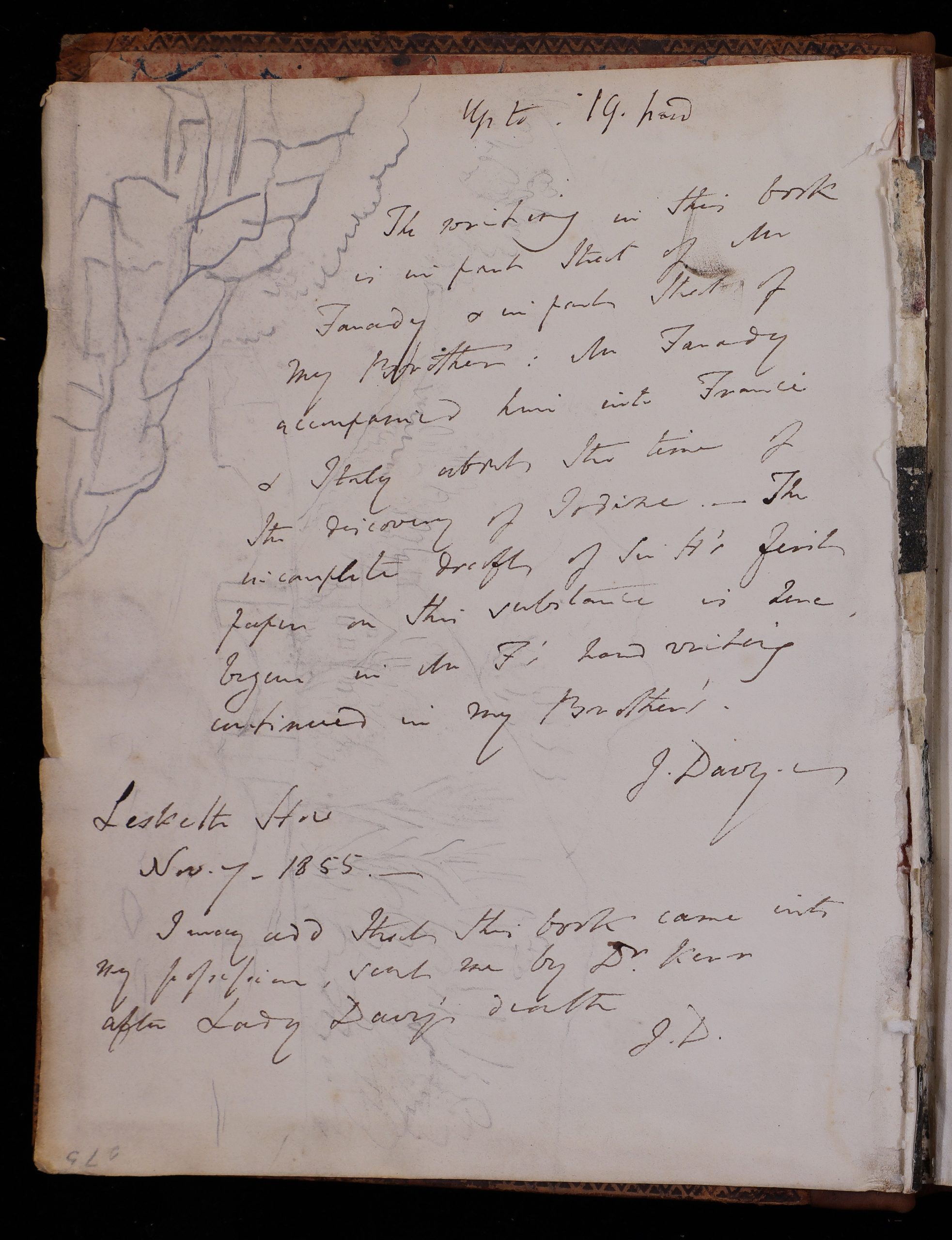

When Davy died in Geneva in 1829, it seems that all his notebooks, which have been digitised by the Davy Notebooks Project, were in his London townhouse, 26 Park Street, Mayfair, in the care of his widow and executrix Jane, Lady Davy (1780-1855). Two of these, the large folio laboratory notebooks, which ‘had several years ago been taken away by Sir H Davy’, belonged to the Royal Institution who, shortly after Davy’s death, successfully asked Lady Davy for their return.[1] Under the terms of Davy’s will, all the other notebooks were passed to his brother John Davy (1790-1868) who took them to Malta where he was serving as an army medical officer. There, during the first half of the 1830s, he used them as a basis for around a fifth of his two-volume biography of his brother, written in response to what he regarded as the scurrilous biography by John Ayrton Paris (1785-1856).[2]

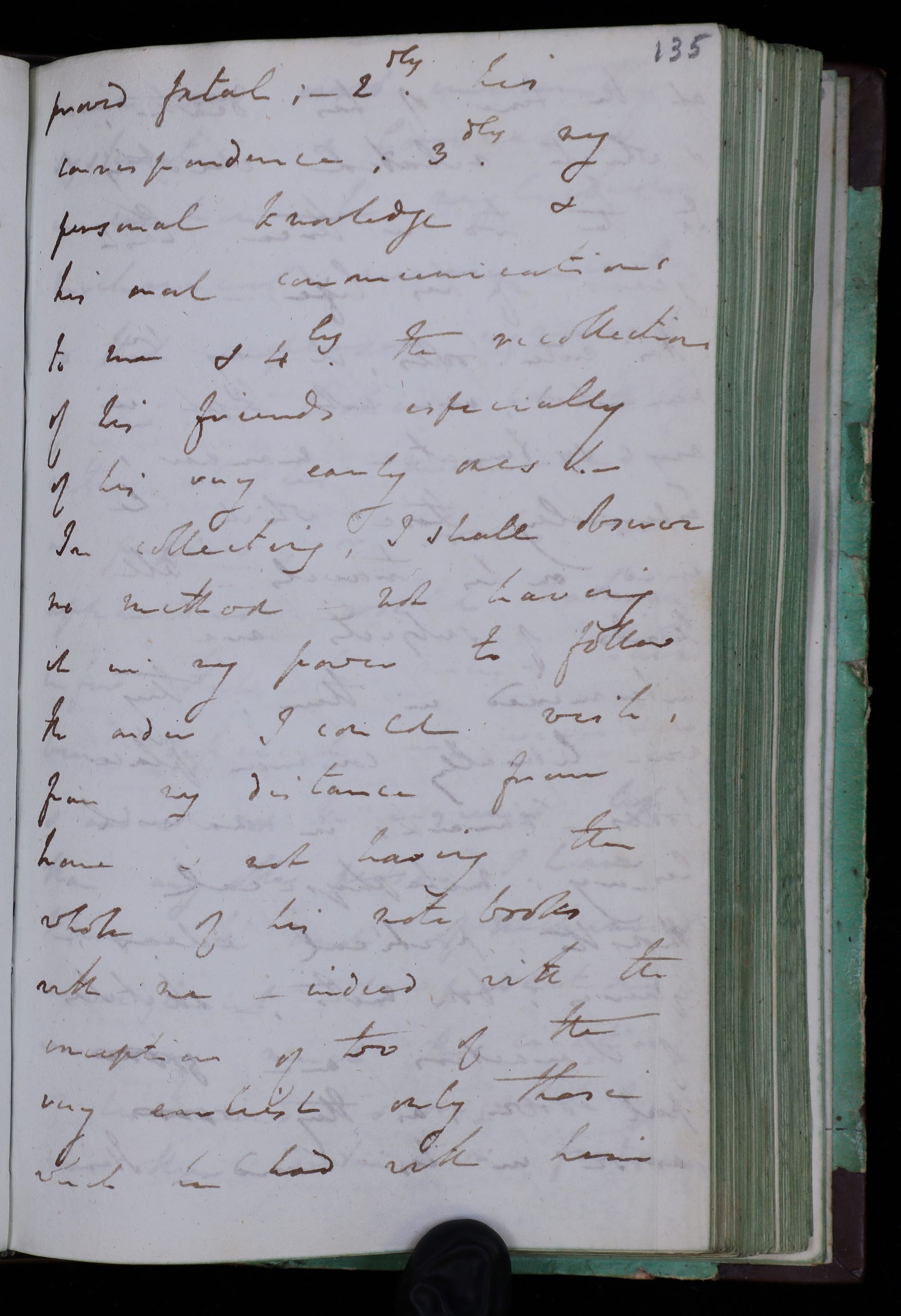

RI MS HD/14/J, pp. 135-36 (click to enlarge)

According to these pages in notebook 14J, when John began penning his brother’s biography in Malta in 1830, he did not have ‘the whole of his notebooks’ with him.

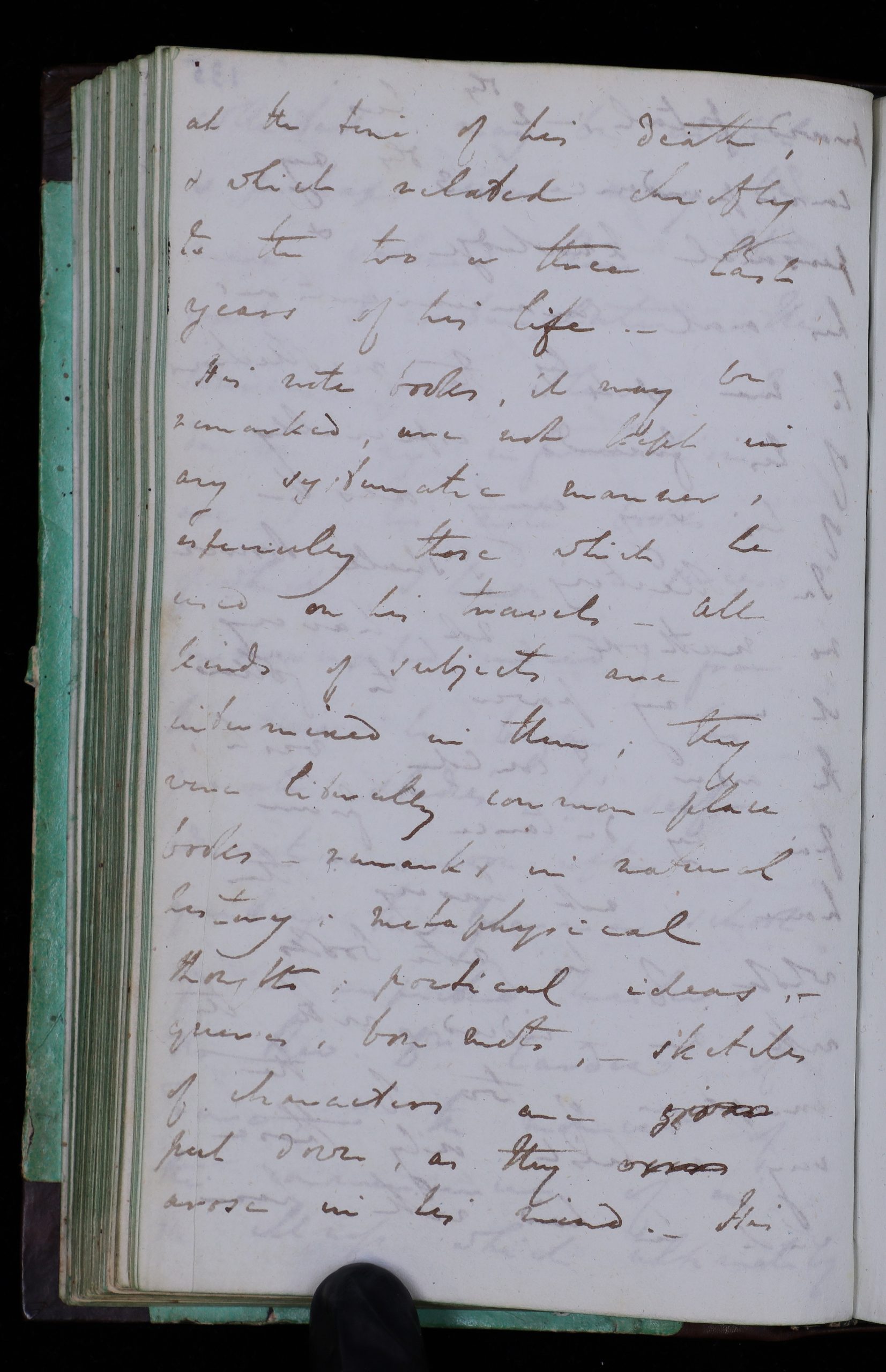

RI MS HD/12, p. 275 (rotated; click to enlarge): One of the notebooks that came into John’s possession after Jane Davy’s death in 1855

Following Lady Davy’s death in 1855, John Davy acquired from her estate additional Davy notebooks which he used in his curiously titled Fragmentary Remains, Literary and Scientific, of Sir Humphry Davy (1858), including Notebook 12.[3] Following John Davy’s death in 1868, Davy’s notebooks and letters passed down through John’s descendants, eventually ending up in the Science Museum, Keele University, Kresen Kernow, and the Royal Institution, which received virtually all the notebooks now in their collections just before the start of the Great War.[4] However, at least four notebooks somehow escaped this process, and although one was purchased by the Royal Institution in 1982 with the aid of a National Heritage Memorial Fund grant, the others have yet to be located.[5] Excluding the laboratory notebooks, bound drafts of his papers, and a stray volume of notes made by John and Margaret Davy, the Royal Institution retains forty-four personal notebooks kept by Davy between 1795 and 1829. [6] These vary in size from quarto to the quite small, 5½ by 4 inches, and in length to between 24 and 366 pages (average 156 pages).

It is not clear how accessible all these notebooks were to scholars between 1914 and the 1950s. In 1914, the Royal Institution’s Assistant Secretary wrote that the donation would not be made public ‘because there would certainly be many applications for permission to peruse [the] documents’, which would not be beneficial ‘to the labours of the Officials of the Institution.’[7] Such an attitude may explain why, during the first half of the twentieth century, studies of Davy were few and far between with almost everything entirely derived from his own publications as well as from Paris’s and John Davy’s biographies and The Royal Institution: Its Founders, and Its First Professors (1871) by Henry Bence Jones (1813-1873).[8]

In the 1950s, serious study of Davy began with the work of June Fullmer (1920-2000), Anne Treneer (1891-1966), Colin Russell (1928-2013), and Harold Hartley (1878-1972). Initially, that research did not involve using the notebooks. Fullmer, in 1960, published an entire paper on Davy’s poetry without reference to the notebooks, though she did cite a manuscript poem held in the Huntington Library.[9] However, four years later she did use the notebooks in a paper on Davy’s gunpowder work.[10] The first two full biographies published in the 1960s, by Treneer and by Hartley, also used Davy’s notebooks. It would appear that Treneer was the first to use those notebooks that had come via John Davy, quoting a couple of poems by Davy from them as well as other matter.[11] In his biography, Hartley not only used the notebooks, but also published images of a few pages.[12] Russell, after publishing two papers on Davy’s electro-chemistry based entirely on printed sources, wrote a third, published in 1963, about what could be learnt from Davy’s notebooks. What is particularly interesting is that this article seems to be the first to cite their Royal Institution manuscript numbers.[13]

In the early 1980s, Margaret Gray (later Woodall) produced a detailed catalogue of all the papers deemed to belong to the Davy collection, which can be accessed via The National Archives website.[14] The catalogue has enabled numerous subsequent scholars to examine Davy’s notebooks in ways not before possible. The work of these scholars demonstrated their enormous historical and literary significance, ultimately leading to the Davy Notebooks Project.

Thanks again to all of our volunteers who have transcribed and who continue to help us in the late stages of the digital edition.

—

[1] These are now RI MS HD/6 and 7. See RI MM, 2 October 1829 (vol. 7, p. 276) and 7 December 1829 (vol. 7, p. 285).

[2] John Davy, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Humphry Davy, 2 vols (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1836). Frank A. J. L. James, ‘Constructing Humphry Davy’s Biographical Image’, Ambix 66 (2019), 214-38 (p. 226). John Ayrton Paris, The Life of Sir Humphry Davy, 2 vols (London: Colburn and Bentley, 1831).

[3] James, ‘Constructing Humphry Davy’s Biographical Image’, p. 233.

[4] Keele University MS Raymond Richards M117-119 includes John Davy, ‘Some Notices of My Life’ (these autobiographical notes have been transcribed and edited by Andrew Lacey and can be found here), volumes of notes made by John Davy and his wife for the Memoirs, and some letters. For details, see James, ‘Constructing Humphry Davy’s Biographical Image’, p. 235. Kresen Kernow GS/6/2-5 comprises five quarto notebooks containing, in Davy’s hand, notes for four geology lectures and one on the history of science.

[5] For a detailed discussion of these processes, see James, ‘Constructing Humphry Davy’s Biographical Image’, pp. 235-36.

[6] RI MS HD/9.

[7] Henry Young to Humphry Rolleston, 16 June 1914, RI MS Rolleston file (uncatalogued).

[8] In addition to a few papers, a couple of biographies were published: Joshua C. Gregory, The Scientific Achievements of Sir Humphry Davy (London: Oxford University Press, 1930) and James Kendall, Humphry Davy: ‘Pilot’ of Penzance (London: Faber and Faber, 1954). The latter did include (p. 73) a small image of a section of the page (RI MS HD/6, p. 61) where Davy recorded his isolation of what he later named potassium. In late 1938, Kendall had given the Christmas Lectures, ‘Young Chemists and Great Discoveries’, and so might have enjoyed special access.

[9] June Z. Fullmer, ‘The Poetry of Sir Humphry Davy’, Chymia 6 (1960), 102-26 (p. 120).

[10] June Z. Fullmer, ‘Humphry Davy and the Gunpowder Manufactory’, Annals of Science 20 (1964), 165-94 (p. 166).

[11] Anne Treneer, The Mercurial Chemist: A Life of Sir Humphry Davy (London: Methuen, 1963), esp. pp. 4-5 and 63-64.

[12] Harold Hartley, Humphry Davy (London: Nelson, 1966), esp. opp. pp. 41, 56, 57, 88, 89.

[13] Colin A. Russell, ‘The Electrochemical Theory of Sir Humphry Davy. Part III: The Evidence of the Royal Institution Manuscripts’, Annals of Science 19 (1963), 255-71.

[14] Frank A. J. L. James and Irena M. McCabe, ‘Collections X: History of Science and Technology Resources at the Royal Institution of Great Britain’, The British Journal for the History of Science 17 (1984), 205-09 (p. 206).