Welcome to another in our series of posts by our lovely volunteers on Zooniverse. This series allows us to learn more about what motivates people to transcribe Davy’s notebooks and what people’s particular interests in Davy might be.

This time we hear from Maria and Jonathan, who are inorganic chemists whose understanding of Davy’s research has been enhanced by participating in the project, and who mention Davy in their inorganic chemistry lectures!

Volunteers in the spotlight: Maria and Jonathan

1. What interests you about the project?

When in-person volunteer opportunities disappeared in March 2020, I started searching for other options – the Davy Notebooks Project turned out to be the perfect fit! I am an inorganic chemist by training, and I discuss some of Davy’s research in an upper-level inorganic course. This project allows me to explore the many facets of Davy’s work – in his own words – which has resulted in a much deeper appreciation of his many and varied contributions.

2. Why are you enjoying it?

This is a unique opportunity to learn more about Davy’s research, his interests, and the history of chemistry from Davy’s remarkable point of view. I am also married to a chemist who joined me on this project early on – we are very much enjoying volunteering together. It has allowed us to discover the details of the experimental approach taken by a remarkable scientist.

3. Do you have any particular interest in Davy?

Our interests initially stemmed from his chemistry research, in particular the discovery and isolation of several elements, his electrochemistry experiments, and his well-known research on nitrous oxide. We now realize this was a rather narrow view of his work – we are in awe of his wide-ranging interests and can much better appreciate the work he describes in his notebooks related to agriculture, geology, medicine, and travel, amongst others.

4. Are sciences and arts ‘separate’?

Absolutely not! Having collaborated on the chemical analysis of several artefacts with a local archaeologist, I consider art and science very much intertwined. The same imagination and creative impulse that inspires the artist in their studio motivates the scientist in their laboratory. Each seeks to interpret and explain the world that they perceive through the medium in which they excel.

5. What have you learned about Davy since joining the project?

What we have discovered by transcribing his notebooks is completely unexpected in some cases – we were not aware of his non-scientific endeavours (poetry, short stories, and travel diaries, as examples). Davy’s eagerness to explore everything from the origins of rock formations to the dimensions of the fins of freshwater fish is palpable in the way that he writes with the same energy and precision on every topic in the notebooks. The joy that Davy feels in just knowing leaps off the page, and his lecture notes show his desire to communicate his many discoveries and to educate any and all that are interested enough to attend his Royal Institution lectures.

6. Do you have any favourite pages of Davy’s notebooks?

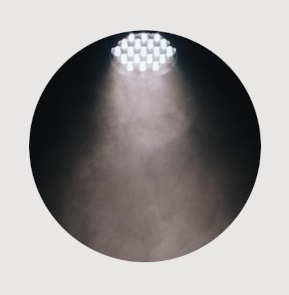

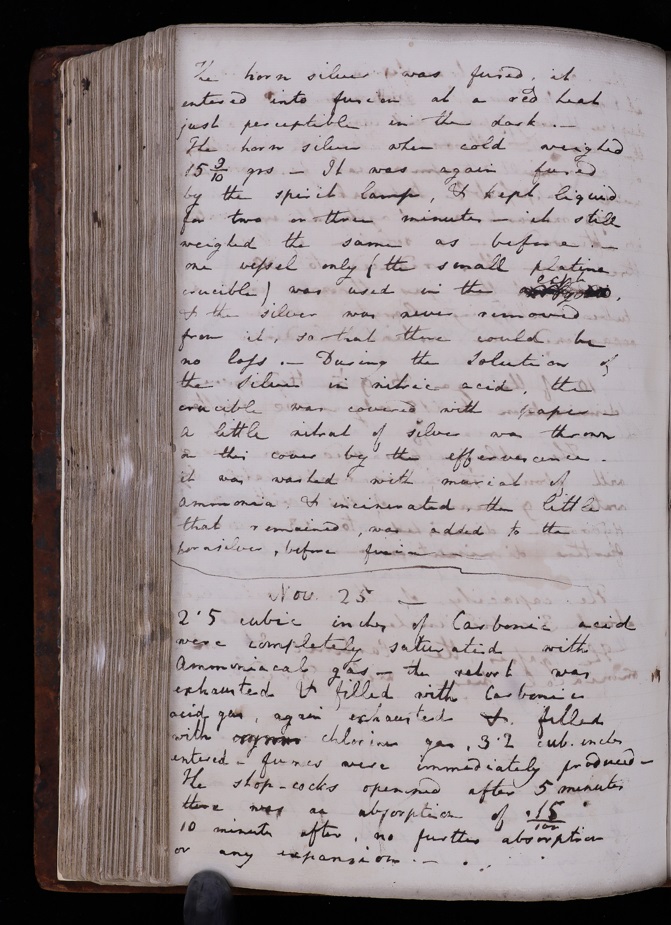

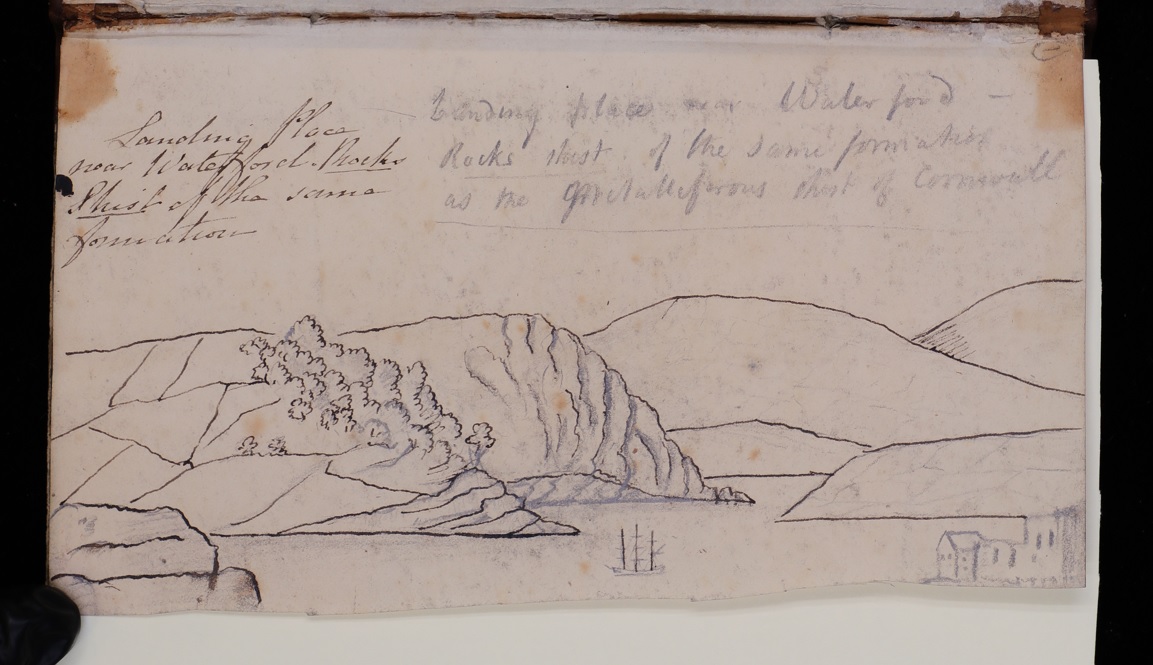

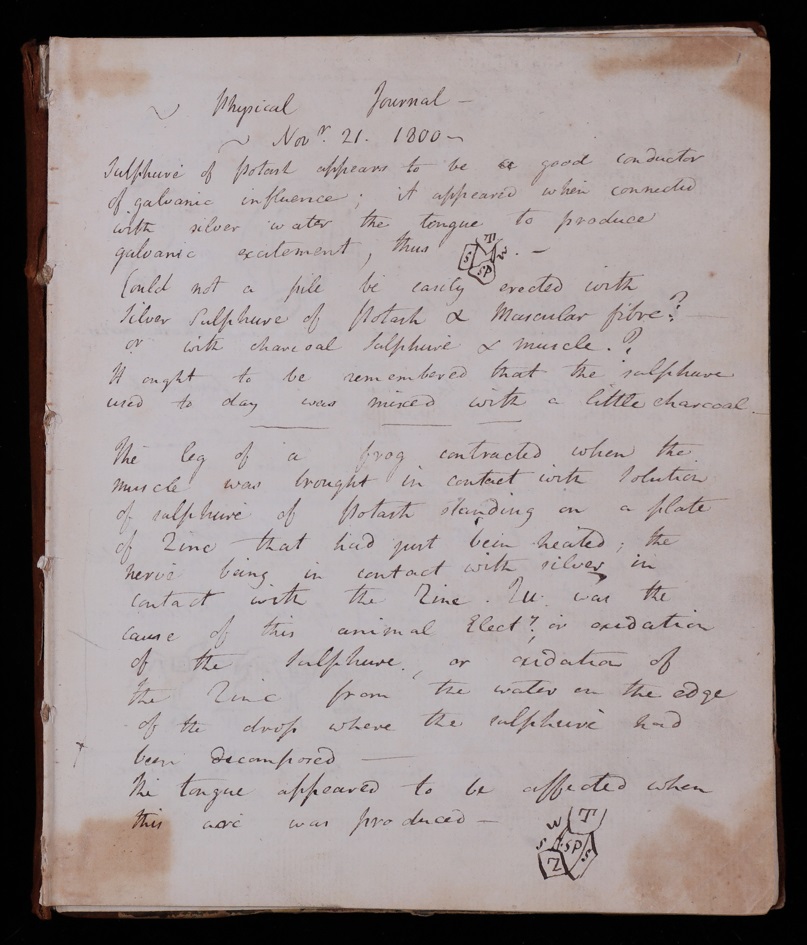

There are so many! Starting with the pages related to his work with oxymuriatic acid and the evolution of inorganic nomenclature and continuing with his lectures related to electrochemical phenomena. In 1810, Davy named chlorine and insisted it was an element not a compound. Notebook 07 contains Davy’s intensive experiments for several months with oxymuriatic acid from mid-1810. On one page, ‘oxymuriatic’ acid is deleted and changed to ‘chlorine’, reflecting the gradual take up of Davy’s new term. Having studied abroad in Ireland, it was wonderful to see Davy’s landscape sketches labeled with geological information. In Notebook 15I, Davy sketches a landing place near Waterford, Ireland, where he noticed a geological similarity with the shist of Cornwall. His scientific diagrams, particularly those where self-experimentation was involved, were quite interesting (and shocking!) to discover. In Notebook 22B, Davy includes a sketch based on the following observation: ‘it appeared when connected with silver water the tongue to produce galvanic excitement’.

RI MS HD/07, p. 404

RI MS HD/15/I, p. 001 (rotated)

RI MS HD/22/B, p. 001

Thank you, Maria and Jonathan!

Ellie Bird