The two earliest notebooks kept by Davy to have survived (RI MSS HD/13/F and /21/A) were both begun in 1795 when he was aged sixteen. The only document written by Davy known from before that year is a brief note to the headmaster at Truro Grammar School, which he attended for the entirety of 1793, sending him a short essay. For the first sixteen years of his life even recent authors have relied heavily, and sometimes uncritically, on the first two biographies written by John Paris (1831, but really an anti-biography) and by Davy’s younger brother John Davy (1836, which goes too far in the other direction). While both these draw on recollections made by those who knew Davy in the 1780s and early 1790s, the latter also draws on a series of notes made by Davy’s sister Katherine following his death in 1829 and also on a quite extraordinary contemporary account of the financial and material support that the surgeon and sometime Mayor of Penzance, John Tonkin, gave to the Davy family until the end of the 1790s.

It seems to me that relying on biographies written in the febrile decade of the 1830s is not an especially reliable way to understand Davy’s early life forty years before. It is important to understand his youth and its contexts, as far as the evidence allows, because aged nineteen he already possessed qualities which enormously impressed Tom Wedgwood and Gregory Watt when they wintered in Penzance in 1797/8. There must have been something in Davy’s background and early life that gave him the extraordinary character and charisma that so attracted their attention.

Viewed from London today, Cornwall perhaps appears to have been somewhat remote in the eighteenth century. But in Falmouth it possessed the first major port in England where landfall could be made from the Atlantic (the officer bringing news of Trafalgar landed there) and until the 1800 Act of Union with Ireland just over 8% of MPs at Westminster were sent by the county, an entirely disproportionate number. Many of the gentry and clergy enjoyed close links with the University of Oxford and as the location of the largest tin and copper mines in the world connections with Welsh and Midland industries were close, hence the presence of Watt and Wedgwood.

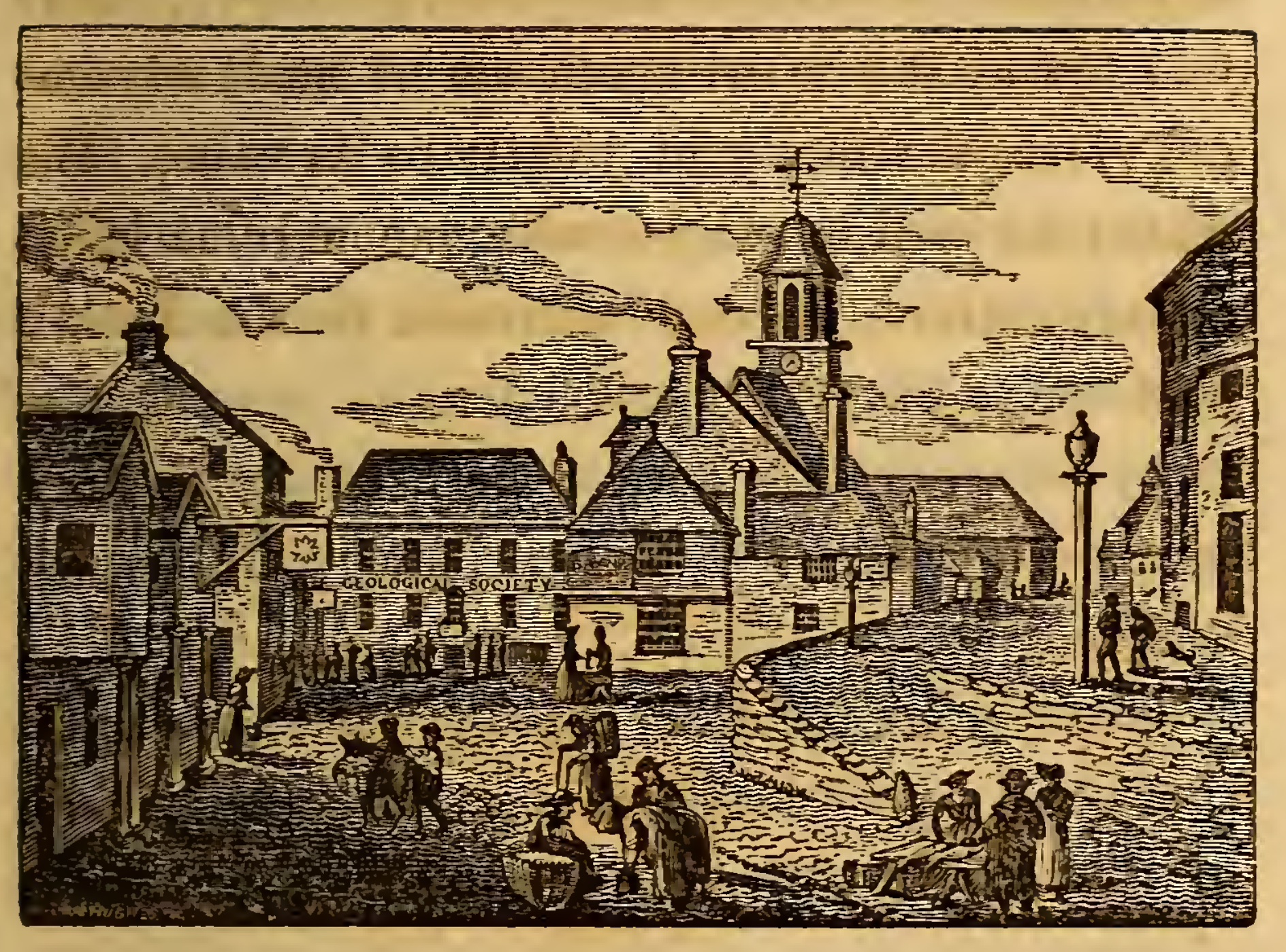

Davy was born in Penzance on 17 December 1778. At least three buildings in the town are claimed to be the location. Such was his fame that by the 1820s guidebooks to Cornwall were noting his place of birth illustrated by fig.1, which identifies the building immediately below the tower of the market building as the place – it should be noted that now very little of eighteenth-century Penzance remains.

Fig. 1

Davy’s father, Robert Davy, is generally portrayed as fairly easy going. Nevertheless, in official documents he is always referred to as a ‘gentleman’ and the Anglicanism of the family, though not especially devout, gave them a social status above the Methodism that had spread in the county. However, during the eighteenth century the fortunes of the Davy family had declined. At the beginning they were of consequence in Ludgvan parish, about three miles north-east of Penzance (top right in fig. 2).

Fig. 2 (click to enlarge)

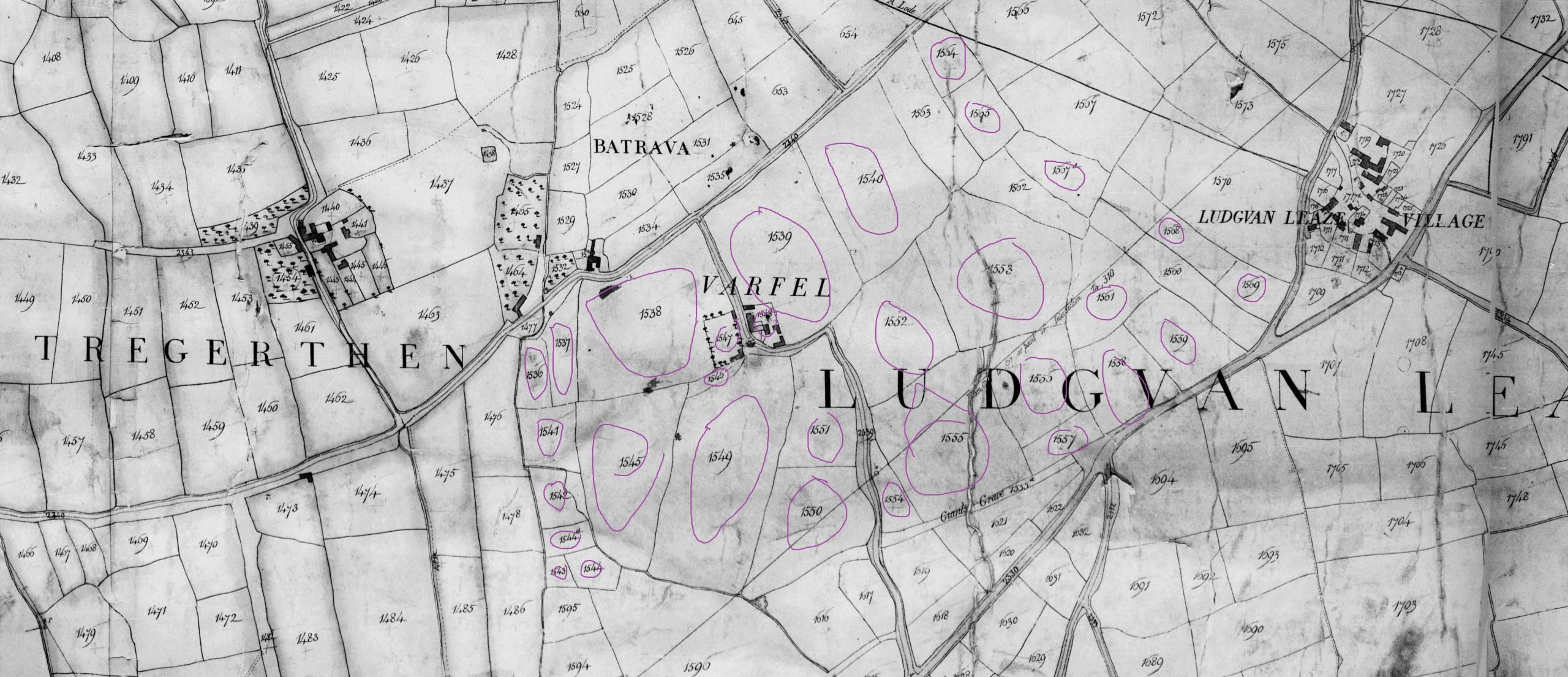

By the 1780s Davy’s branch of the family only retained the lease (from the Dukes of Bolton) of a seventy-nine-acre farm centred on Varfell, immediately to the south of Ludgvan (the fields he farmed are picked out in purple ink on fig. 3 which is now a daffodil farm, fig. 4) together with a grist mill and a small amount of land in the village.

Fig. 3 (click to enlarge)

Fig. 4

Robert Davy built a house in Varfell, still standing (fig. 5). Put differently, Robert Davy was a respectable yeoman farmer, a class that has now disappeared entirely, right at the bottom of the gentry.

Fig. 5

When he reached school age, Davy’s time was divided between living in Varfell and staying with Tonkin in Penzance. From his grandmother, who lived in the town, Davy learnt about Cornish legends and myths. These would have included stories about St Michael’s Mount, which is on the coast immediately south of Varfell and visible from the house where fig. 6 was taken.

Fig. 6

The Mount exerted an enormous influence on Davy’s imagination expressed over the years in drawings in his notebooks and in a whole series of poems written and redrafted throughout his life.

From around 1785 he attended Penzance Grammar School where he presumably learnt the Classics in an Anglican context. He was popular with his school fellows as he helped them with their work and he would apparently give them impromptu talks by the Star Inn (on the left in fig. 1). At this time, he also began his life-long passion for fishing and even at the most difficult times of his life, he would frequently leave London for a weekend’s fishing in the Chilterns or on the River Test. Indeed, much of the last two years of his life was spent fishing on the River Sava in what is now Slovenia and the last book he published before his death was entitled Salmonia.

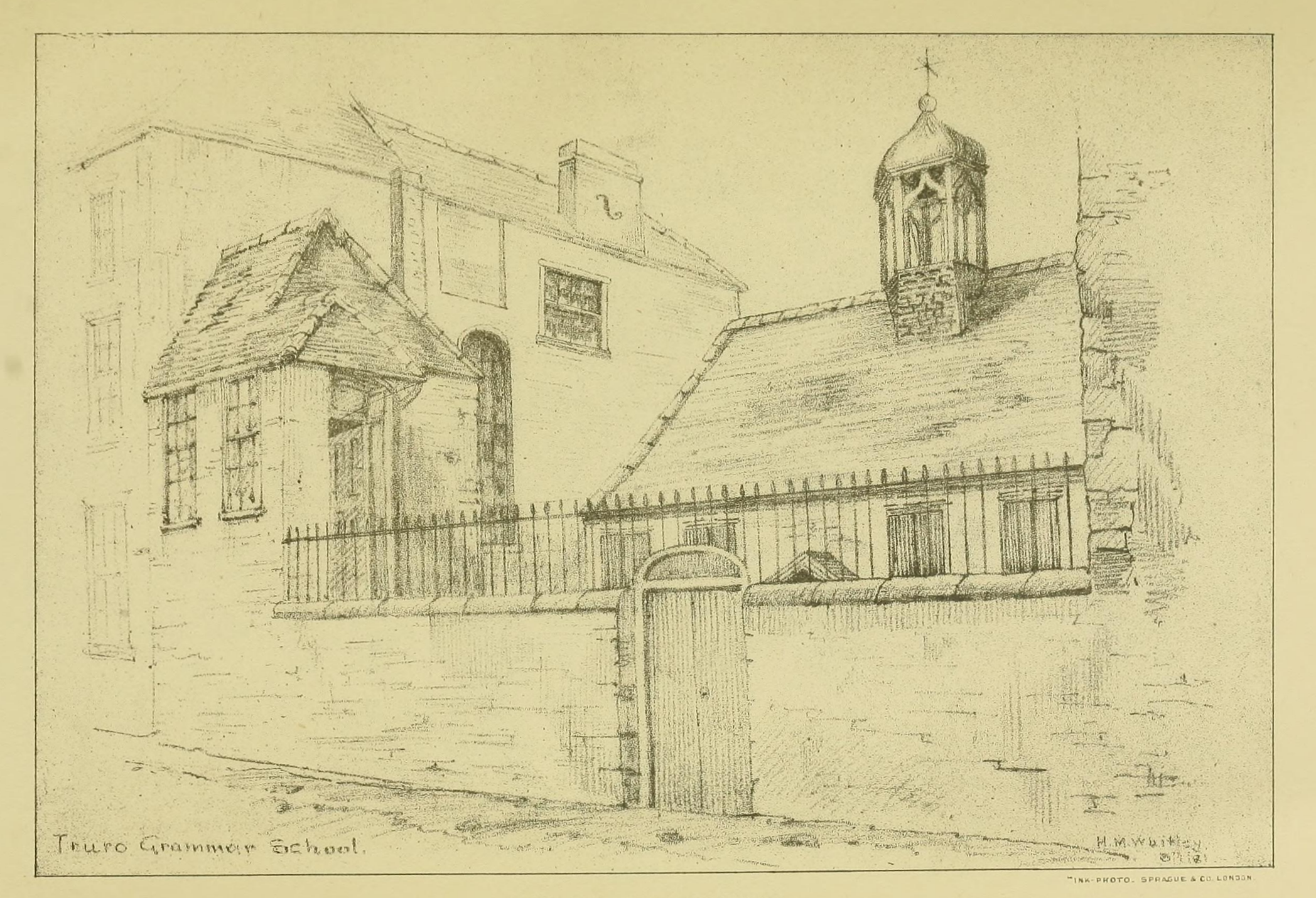

Tonkin paid for Davy to attend Truro Grammar School (fig. 7) throughout 1793 where he would have continued to a more advanced level the studies he had commenced in Penzance.

Fig. 7

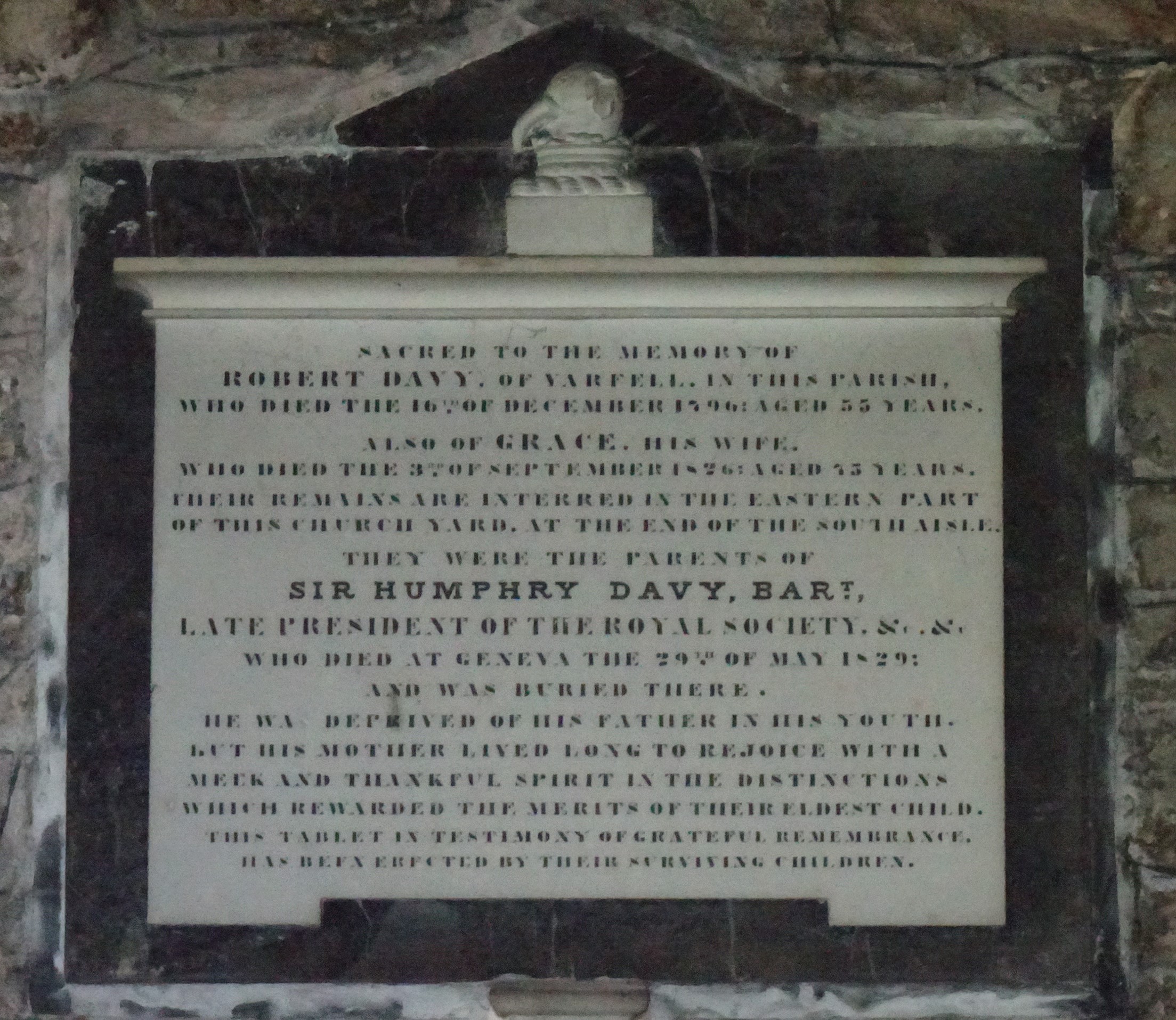

For reasons that are unclear he left at the end of the year and very little is known about what he did during 1794. But at the end the year, precisely a week before Davy’s sixteenth birthday, his father died, in serious debt owing to unwise mining investments. He was buried in the graveyard of Ludgvan Parish church (figs. 8 and 9). Later a plaque (fig. 10) was placed inside the church commemorating Davy’s mother and father, though a casual visitor might well be forgiven for thinking it was to Davy. Extraordinarily the plaque gives both an incorrect day and year for Robert Davy’s death.

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10 (click to enlarge)

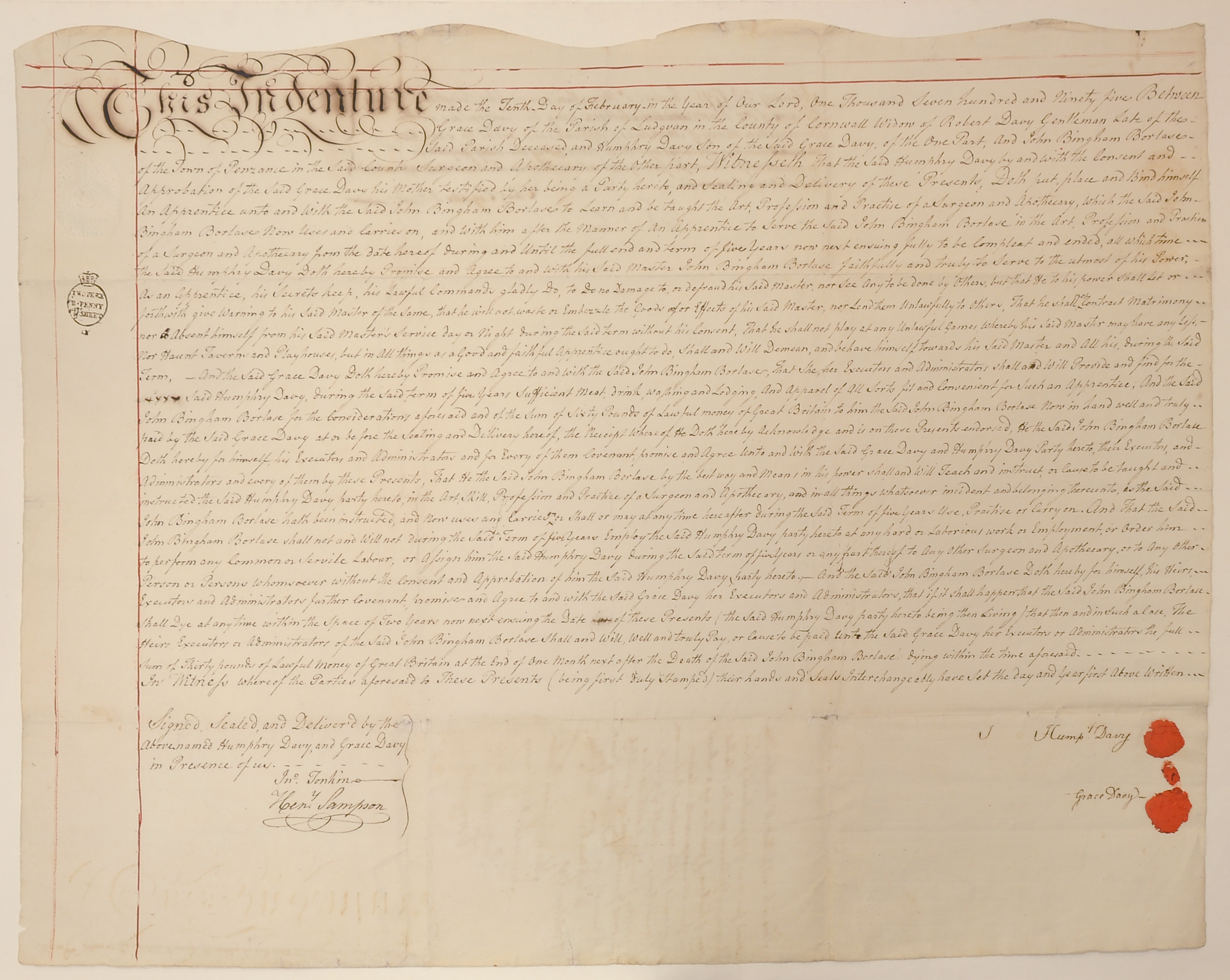

As a consequence of his father’s death, his mother immediately apprenticed Davy for five years to the Penzance surgeon and apothecary, John Bingham Borlase, the premium, once again, being paid by Tonkin (fig. 11).

Fig. 11 (click to enlarge)

There was some vague idea that once he had completed his apprenticeship, Davy would then study medicine at the University of Edinburgh, a suggestion that receives some evidential support by the short duration of the indenture. It cannot be a coincidence that it is from this period that Davy began his notebooks. One mostly contained his transcription of Euclid’s Elements (21/A) and the other (13/F) a miscellany of poems, philosophical writings, and the like – but not a trace of anything remotely chemical or geological.

When just under three years later, Watt and Wedgwood arrived in Penzance, they found in Davy someone whom they clearly appreciated had enormous potential. Watt, who lodged with Davy’s mother, particularly seems to have turned Davy’s attention to chemistry and within a few months Davy wrote a long essay critiquing on both experimental and theoretical grounds the work of the leading, recently guillotined, French chemist Antoine Lavoisier proposing an alternative to Lavoisier’s theory of calorique. While an audacious essay that in its printed version Davy soon came to regret, Watt gave it to the radical (Jacobin) physician Thomas Beddoes just then establishing the Medical Pneumatic Institution at Clifton, near Bristol. The essay gave Beddoes the confidence, along with strong support from Watt and others, to appoint Davy (without interview) in October 1798 as Superintendent of his new Institution. From that position his spectacular career trajectory flowed.

The story of how Davy came to make this crucial major move from Penzance to Bristol illustrates that Cornwall was not then some kind of provincial backwater, but a county where individual talent could be nurtured and recognised. However, it was not a place where national or international careers could be built and Davy, and later his brother, left the county only to return, infrequently, on family visits. But the memory of Cornwall from his early youth, its landscapes, its people, its myths, remained with him, all of which found expression in his later notebooks.