Vocal learning in developmental dyslexia

If you’ve ever had the experience of your mouth being numbed at the dentist, then you’ll know how difficult it is to speak without being able to feel any tactile sensory feedback! A new theory suggests that developmental dyslexia may involve difficulties with processing how the mouth feels when producing speech.

Being unable to effectively process how our mouth feels when producing speech may interfere with our ability to learn new speech sounds. Learning new speech sounds mostly takes place during infancy through babbling (‘bababa’). However, the way we pronounce speech sounds can be changed under specific circumstances throughout our lives.

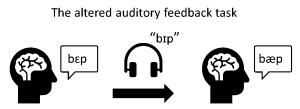

The altered auditory feedback task

We can explore vocal learning in older children and adults using the altered auditory feedback task. In this task, a participant will repeat a spoken syllable (for example, ‘bɛp’; ɛ pronounced as ‘e’ as in ‘bed’) while hearing their own voice through headphones in real-time.

The vowel sound of the spoken syllable is then changed over time using a computer program (for example, to ‘bɪp’; ɪ pronounced as ‘i’ as in ‘bin’). As a result, what the participant hears sounds different from the originally spoken syllable. Interestingly, participants are almost always unaware that their voice sounds different but still change their speech without realising to make up for it (for example, to ‘bæp’; æ pronounced as ‘a’ as in ‘bad’).

Altered auditory feedback task image

Figure shows the typical compensatory response to altered auditory feedback .

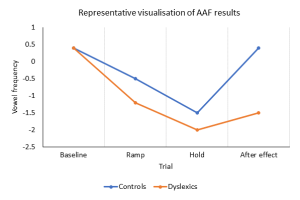

This task has been used to explore vocal learning in people with dyslexia. For example, adults and children with developmental dyslexia change their speech more than typical readers when their speech has been manipulated to sound differently.1,2 Additionally, when the manipulated auditory feedback is turned off, adults and children with developmental dyslexia take longer to return to pronouncing the syllable as they were originally told1,2.

Representative data adapted from van den Bunt et al. (2017)1 shows more deviation from and slower return to baseline in the dyslexia group.

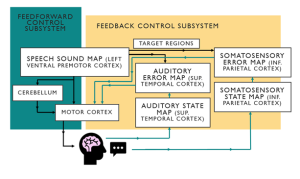

The Directions Into Velocities of Articulators (DIVA) model

To explain why people with dyslexia may behave differently during the altered auditory feedback task, data1 was inputted into a computer program called the DIVA model.3 This model attempts to explain how we produce speech and learn new speech sounds.

It suggests that for every speech sound a person has learnt (for example, ‘ta’), there are speech sound map cells that represent that sound. When we speak, signals are sent from speech sound map cells to the motor cortex. If the sensations produced by speech don’t match what the brain expects, then signals are sent to the motor cortex to correct any errors in speech production.

Adapted from Guenther et al. (2006)3. Diagram to show how different areas of the brain are theorised to interact during speech production according to the DIVA model.

The DIVA model revealed that information about how the mouth feels when producing speech may not be processed as effectively by an area of the brain called the somatosensory cortex in developmental dyslexia. The somatosensory cortex is responsible for making sense of bodily sensations, such as touch and temperature.

If people with developmental dyslexia aren’t processing tactile information effectively when speaking, they may overly depend on what they can hear instead. This could explain why people with developmental dyslexia were found to change their speech more than typical readers in response to auditory manipulation of their speech.

Our current research project

Based on this previous research, we are carrying out a project (led by Dr. Groen of Lancaster University) to explore the role of the somatosensory cortex in vocal learning using a neuroscientific technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). TMS can be used to decrease brain activity in a targeted brain area – but thankfully it is temporary and safe!

We will use TMS to disrupt activity in the somatosensory cortex during the altered auditory feedback task, allowing us to test whether the somatosensory cortex contributes to vocal learning. We might expect to find that typical readers will begin to behave more like people with developmental dyslexia by adapting their speech more during the task.

Photo of TMS equipment taken by Tieghan LeRoy

The clinical implications of our research

Our research is important because children with developmental dyslexia continue to struggle with reading even after receiving extra support.4 Furthermore, the NHS predicts that up to 1 in 10 people have developmental dyslexia in the UK. If our expectations are confirmed, then we should explore whether it would be beneficial to supplement current reading interventions with tactile interventions. For example, we could encourage children with dyslexia to be more mindful of how their mouth feels when producing different speech sounds.

If you would be interested in hearing more about our project (and potentially participating yourself!), then please contact me at gibbsm1@lancaster.ac.uk.

Further reading:

- van den Bunt, M. R., Groen, M. A., Ito, T., Francisco, A. A., Gracco, V. L., Pugh, K. R., & Verhoeven, L. (2017). Increased response to altered auditory feedback in dyslexia: A weaker sensorimotor magnet implied in the phonological deficit. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(3), 654-667.

- Van Den Bunt, M. R., Groen, M. A., van der Kleij, S. W., Noordenbos, M. W., Segers, E., Pugh, K. R., & Verhoeven, L. (2018). Deficient response to altered auditory feedback in dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology, 43(7), 622-641.

- Guenther, F. H., Ghosh, S. S., & Tourville, J. A. (2006). Neural modeling and imaging of the cortical interactions underlying syllable production. Brain and language, 96(3), 280-301.

- Van der Kleij, S. W., Segers, E., Groen, M. A., & Verhoeven, L. (2019). Post-treatment reading development in children with dyslexia: The challenge remains. Annals of Dyslexia, 69(3), 279-296.

This blog post has kindly been contributed by Melissa Gibbs