What happens when you bring together three people interested in communication around dementia and a specialist in sport communication? The Public Discourses of Dementia team, Gavin Brookes and Emma Putland, recently had the pleasure of collaborating with Felicity Slocombe from the University of Bradford’s Centre for Applied Dementia Studies and with Hannah Thompson-Radford, a Senior Lecturer in Sport Communication and Journalism at Swansea University. Together, we asked: how are football, traumatic brain injury and dementia represented in the British Press and how might this contribute to wider discussions surrounding dementia risk and support?

Context: Traumatic brain injury, football and the news

Traumatic brain injury is when the brain is injured through a trauma to the head (head injury) and it has been recognised as one of 14 potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia, accounting for approximately 3% of dementia diagnoses (Livingston et al., 2024). There are many possible causes of traumatic brain injury, such as traffic accidents and falls. Evidence has been building that frequently heading the ball in (professional) football can increase the risk of head injuries and dementia. At the same time, exercising has also been linked to a lower dementia risk; this necessitates balancing the promotion of physical activity whilst acknowledging the potential dangers of some sports and working to better protect players.

Football is the UK’s top sport, being followed by approximately 80% of British people. Campaigners have pushed for over twenty years to better protect and support affected players.

In response to increasing evidence, UK football has begun to introduce limits on heading in training and a phased complete heading ban for youth football (you can read England Football’s guidance here). These restrictions depend on buy-in from both individual players and football organisations. Entirely removing heading would likely meet resistance; equally, players and coaches argue that heading is a smaller cause of concussion than head-to-body contact (Parsanejad et al., 2023).

The news media plays a powerful role in shaping public understanding and interest in this issue, and some UK national newspapers have been campaigning for up to 10 years about the link between traumatic brain injury caused by headers, collisions and falls in football and subsequent dementia diagnoses. Considering the amount and length of coverage, it is useful to zoom out and look for key linguistic patterns to better understand the reporting of this issue.

What words are often used alongside ‘football*’?

This blog reports on our analysis of a collection of 11,372 national newspaper articles that discussed dementia across a decade, from the 1st of January 2013 to the 31st of December 2022, totalling over 9 million words. This included eight national newspapers (Express, Guardian, Independent, Mail, Mirror, Star, Telegraph, Times), including their online, Sunday and ‘sister’ editions. We found that ‘football*’ (with the * allowing for alternative endings such as ‘footballer’) was mentioned 10,852 times across 1,836 news articles, which was far more than any other sport or sport in general (‘rugby*’ is second most mentioned, with 2,726 uses across 527 texts).

Here, we examine frequent linguistic patterns surrounding the word ‘football*’. To identify these patterns, we looked for words that frequently occurred near to ‘football*’ (these words are called collocates and here, they must have occurred at least 100 times within the span of five words to the left and/or right of ‘football*’). Table 1 shows the top 40 collocates of football.

Table 1. The top 40 collocates of ‘football*’, calculated using Dice coefficient.

| Primary context of use | Collocates (words that co-occur with football*) |

| Risk and research | Heading, between, link, playing, times, dementia, likely, into, links, more, in, and, found, among, study, disease, research. |

| Stakeholders and their perspectives/actions | Professional, former, Association, ’, players, Scottish, authorities, league, Football, English, Tackle, ‘s, who, campaign. |

| Other sports | American, rugby. |

| Other | has, are, the, of, that. |

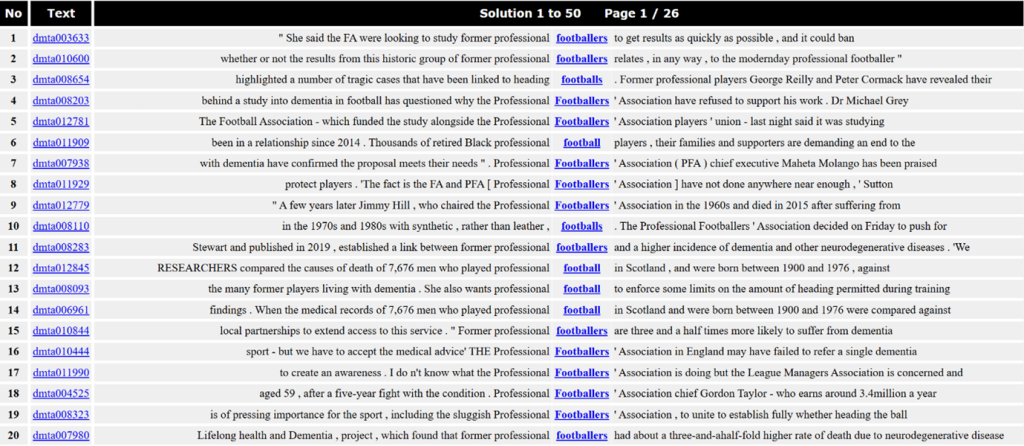

We then we read 100 random examples of how each of the top 40 collocates were used alongside football* in the newspapers, totalling 4,000 examples (see Figure 1 for an example of what this looked like).

Figure 1. A screengrab showing how concordance lines appear in the programme that we used, called CQPweb. Here, ‘football*’ occurs alongside its collocate ‘professional’. Each of these lines could be expanded to read more of the text.

Throughout this blog, collocates are italicised when found within five places to the left or right of ‘football*’, while the search term ‘football*’ is in bold (and italicised if it is also a collocate, as with examples 7 and 11 presented later). ‘Traumatic brain injury’ will be abbreviated to ‘TBI’.

A debated but increasingly certain link

The link between heading the ball in football and sport-related TBI and/or dementia is debated, becoming increasingly certain over time, as shown by examples 1-3.

(1) ‘There is not yet enough firm evidence to link heading footballs to brain injuries.’ (MailOnline, 2018)

(2) ‘And now they finally have evidence. There is a casual [sic] link between professional football and dementia. It’s an undeniable fact for a game that has been too happy to stay in denial.’ (Daily Mail, 2019)

(3) ‘Groundbreaking research has already found that footballers are three-and-a-half times more likely to die from degenerative brain diseases such as dementia, and previous studies suggest even 20 headers can have an impact on brain function.’ (Daily Mail, 2021)

While newspapers tend to foreground the elevated risks of TBI and dementia, there are some attempts to balance consideration of these risks with the health benefits of playing sport, too. Dr William Stewart, whose ‘groundbreaking research’ is mentioned in example 3, is shown in example 4 to provide further context about the overall health implications of sport:

(4) ‘Yet he emphasises that his research should not discourage people from playing sport. Alongside higher rates of dementia, his research revealed that former footballers have significantly lower rates of cardiovascular disease and some cancers than the rest of the population.

Sport helps you live longer.’ (The Times, 2019)

Conflict

As example 2 implies and examples 5-7 make more explicit, the increasing evidence of a link between (professional) football and dementia is frequently represented in relation to a conflict, whether between different stakeholders or against dementia. This is signalled through the prevalence of a conflict metaphor (‘battle’, ‘fight’, ‘victory’, etc.).

(5) ‘Battle to get brain injury among footballers recognised as an industrial disease – which would mean affected players being able to claim state disability benefits – is realistic, says expert.’ (MailOnline, 2020)

(6) ‘SIR ALEX FERGUSON and Sir Kenny Dalglish have joined forces to support football‘s fight against dementia.

The duo will join England manager Gareth Southgate in a one-off event to raise funds for research into the link between football and the disease – in conjunction with Sportsmail’s campaign – and support those suffering from dementia and their families.’ (MailOnline, 2020)

(7) ‘A study into the link between football and dementia was finally commissioned yesterday following an 18-month campaign by The Daily Telegraph exposing what has been branded sport’s “silent scandal”. […] Confirmation of the study was a victory for The Telegraph and the victims of the killer illness – including several members of England ‘s 1966 World Cup-winning team – as well as the families who had campaigned for many years for the game to investigate.

Chief among them was Dawn Astle, the daughter of West Bromwich Albion legend and former England striker Jeff, whom a coroner ruled in 2002 had been killed by repeatedly heading a football. Admitting she had been “quite teary” following the announcement, she thanked the media for its support, adding: “It’s been lonely a lot of the time and it’s pure frustration at times when you know, because it said on my dad ‘s death certificate, that football killed him and football didn’t want to know.’ (Daily Telegraph, 2017)

Conflict metaphors are widely used in media portrayals of both football and dementia. Dementia has frequently been positioned as a ‘killer illness’, with many ‘victims’, and so it is often rendered an invisible enemy that society must ‘fight’ (examples 6,7; Putland & Brookes, 2024). In this context, while dementia can be positioned as the enemy (6), more frequently, the opponent in this conflict is the game of ‘football’ and the organisations that determine its regulations and activities, as exemplified by the claim that ‘football killed him and football didn’t want to know’ (7). Here, football, not dementia, is personified as the killer and as refusing to acknowledge this. Notably, ‘football’ may refer to both the role of the sport in Jeff Astle’s death (“repeatedly heading a football”) and to the institution of football (those involved at an organisational level) who are construed as having abandoned Astle.

As the examples show, the newspapers explicitly align themselves with a coalition of stakeholders, most often of researchers, charities, the media, footballers and their families, that strive to firstly prove the link between football, TBI and dementia, and secondly, to improve the support provided for all footballers. Indeed, the collocates tackle and campaign can be primarily attributed to the references that newspapers make to their own campaigns (namely, the Telegraph Sport’s 2016 ‘Tackle Football‘s Dementia Scandal’, the Sunday Mail‘s 2017 ‘Football‘s Timebomb’ and Sportsmail’s 2020 ‘Enough is ENOUGH’ campaigns). Examples 6 and 7 exemplify this meta-discursive practice, with the newspapers foregrounding their role in ‘exposing’ scandals and providing ‘support’ to advocates in campaigning for change.

Continuing in this vein, newspapers consistently foreground criticisms of football organisations’ (in)action (8,9), alongside attributing responsibility to these authorities to do their ‘duty’ to ‘protect players’ and ‘help’ everyone affected (10) and celebrating their campaigns’ ‘victor[ies]’ when, as example 7 illustrates, these organisations are sufficiently pressured to act. Football organisations are frequently generalised as ‘football authorities’ (e.g., when discussing ‘the shameful inaction of the footballing authorities’; Daily Mirror, 2022) or even as ‘football’ (7,8,10). Specific organisations are also often discussed, notably the Football Association (FA) and the player advocacy organisation, the Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA) (8,9).

(8) ‘The Professional Footballers Association gave £240 towards physiotherapy sessions after Allan suffered a stroke, but Christine claims it declined to help with his dementia. She added: ” It [sic] think it is a disgrace that football isn’t doing more.” Anger at the lack of help for players with dementia is fuelled by the vast amount of money flooding into the sport.’ (Daily Mirror, 2017)

(9) ‘Sutton’s professional footballer father, Mike, died on Boxing Day following a 10-year battle with dementia. And the player-turned-pundit has spearheaded Sportsmail’s campaign for research funding, temporary concussion substitutes and limited heading in training to protect players. ‘The fact is the FA and PFA [Professional Footballers’ Association] have not done anywhere near enough,’ Sutton said. ‘They have ignored, shunned, turned their backs on a massive issue. Hundreds of players have died. My father among them. And we do not even know what has happened in the amateur game.’’ (MailOnline, 2021)

(10) ‘All of football has a duty to get this right, to protect players, to help the families enduring the cruel sight of their loved ones being dragged away from them by dementia.’ (The Times, 2019)

Footballers with dementia

As the above examples illustrate, combining statistics (3) and expert opinions (4,5) with personal stories (7,8,9) and emotive language (7,9,10) is central to the media’s campaigning to address the link between football, TBI and dementia. Often, as with examples 7-10, newspapers take the perspective of the family members of former professional footballers with dementia. Regularly, the footballers themselves who have been diagnosed with dementia are passivised and victimised, perhaps best exemplified by their discursive positioning as ‘the victims of the killer illness’ and as families’ ‘loved ones being dragged away from them by dementia’ (7,10). This is not always the case, though, and examples 11 and 12 are noteworthy anomalies within this broader positioning of footballers with dementia:

(11) A PIONEERING England women’s footballer has blamed her dementia on heading the ball as a child and called for it to be banned for under-12s.

Sue Lopez, 74, played for England between 1969 and 1979 and was diagnosed with the disease in 2018.

Sue said: “I think my dementia has been caused by the heading of football. Anything to do with football now, I think, ‘I hope people are being more careful now and not no[w] be letting young kids head the ball’”. (Daily Mirror, 2020)

(12) He sought no sympathy for his condition, merely the opportunity to raise awareness of its wider impact and encourage other sufferers to come forward. Asked if the competitor in him had made it difficult to speak out, Calderwood replied: “Yes, you try and hide it. But the message to others is not to be afraid to come forward and talk about it.” […] One of Scottish football’s bubbliest characters, he remains philosophical about the disease. “Strangely, it hasn’t been too bad,” he said. “I’ve just got on with things.” (The Times, 2017)

Examples 11 and 12 are unusual for multiple reasons. Most notably, both directly quote former footballers after their dementia diagnosis, attributing to each the agency to speak about their experiences and advocate for change. Example 11 features a former female footballer, whereas coverage overwhelmingly orients around men’s football overall. Meanwhile, the footballer in example 12 presents life with dementia as not ‘too bad’, which contrasts the usual emphasis on suffering and challenges the fear and stigma surrounding dementia, reinforced by example 13.

(13) If we are going to bring the link between dementia and football out of the shadows, and release the stigma attached to it, now is the hour. (Daily Star, 2021)

Example 13’s metaphorical positioning of the link between dementia and football as in the shadows (and thus needing to be brought to light) is reminiscent of earlier examples’ discussions of no longer trying to ‘hide’ dementia and of ‘exposing […] sport’s “silent scandal”’ (12, 7). Throughout, advocates and the media alike are positioned as raising awareness and pressuring football authorities to “see” and respond appropriately to the cognitive risks associated with the current practices in football.

Final thoughts

Between 2013 and 2022, newspaper reporting appears to have shifted towards increasing certainty regarding the link between football and dementia risk from TBI, which is in line with research. While the positive health benefits of sport are sometimes considered, football is primarily represented in relation to increased dementia risk. Drawing on a conflict metaphor, the newspapers consistently align with footballers and their families (and researchers, other media and charities) working against a shared opponent: either dementia or football authorities. Newspaper-led campaigns explicitly aim to pressure football organisations to fund research and implement changes to mitigate dementia risk and support people affected. These football-oriented campaigns offer an excellent example of the advocacy role that the news media can take on to promote public understanding of an issue and encourage institutions (here, football authorities) to take action.

Within this, it is worth further scrutinising how the main beneficiaries of these campaigns – footballers – are positioned. While newspaper campaigns aim to improve football’s support for impacted players, the articles frequently passivise and victimise footballers with dementia. This risks perpetuating dementia stigma, consistent with media portrayals of dementia more generally (Putland & Brookes, 2024). Former footballers with dementia are seldom heard in these examples, which reflects a broader pattern of exclusion of the voices of people with dementia. This is especially the case for women, with the newspapers overwhelmingly foregrounding male former footballers, particularly members of England’s 1966 World Cup-winning squad (five of whom have died with dementia). Meanwhile, women’s football is backgrounded almost to the point of being absent. The notable exception in this dataset is Sue Lopez MBE, one of the earliest ‘official’ England women’s players and member of the English Football Hall of Fame, who has spoken out about her belief that her dementia was caused by heading the football (example 12). Lopez made her debut for Southampton in 1966 and her ‘official’ England debut [1] in 1973, making her of a similar generation to the 1966 men’s squad. Despite Lopez being an ideal candidate for inclusion (indeed, Sportsmail featured an article on Lopez and her dementia earlier in the same year), it is worth noting that Sportsmail’s 2020 campaign launch uses an all-men image of 28 footballers who have/had dementia.

We hope that this blog can spark some reflection and discussion about the link between football, traumatic brain injury and dementia, and about how the news can play an important role in shaping societal understanding and action on a range of issues. This is a dynamic topic and we are interested to see how this issue continues moving forward…

References

Livingston, G., Huntley, J., Liu, K. Y., Costafreda, S. G., Selbæk, G., Alladi, S., … & Mukadam, N. (2024) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. The Lancet, 404(10452), 572-628.

Parsanejad, E., McKay, M.J., Ross, A.G., Pappas, E, & Peek, K. (2024) Heading in football: Insights from stakeholders in amateur football. Science and Medicine in Football, 8(3), 212-221.

Putland, E., & Brookes, G. (2024). Dementia stigma: representation and language use. Journal of Language and Aging Research, 2(1), 5-46.

[1] Sue Lopez played for England in the unofficial World Cups in 1970 & 1971 but was not recognised ‘officially’ until her 1973 debut when she was given cap number 18.

About the authors:

Dr Emma Putland is a Senior Research Associate on the UKRI-funded ‘Public Discourses of Dementia’ project in the Department of Linguistics and English Language at Lancaster University (UK). Her research focuses on health and communication, particularly regarding ageing and dementia, alongside discourses concerning the environment and related crises.

Dr Felicity Slocombe is a Lecturer in Dementia Studies at the University of Bradford’s Centre for Applied Dementia Studies (UK). Felicity is interested in exploring communication with and to people living with a dementia including how media discourses around dementia are experienced and perceived by different people.

Dr Hannah Thompson-Radford is a Senior Lecturer in Sport Communication and Journalism at Swansea University (Wales). Her research focuses on the intersections of sport sociology, sport media, and sport communication, with a particular emphasis on gendered perspectives in both representation and lived experiences.

Dr Gavin Brookes is Reader in Linguistics and UKRI Future Leader Fellow in the Department of Linguistics and English Language at Lancaster University (UK). He specialises in corpus linguistic, critical, and multimodal approaches to discourse analysis, with a particular focus on language used about health and illness and in health(care) contexts.