Why look at eyes, gaze and vision?

Eyes and vision have great cultural significance: eyes are seen as “windows to the soul” and in (Western, neurotypical) societies, eye contact has been associated with trust, confidence, attention, social recognition, inclusion and rapport building – although of course this is context dependent (Jarrett, 2019; Jongerius et al., 2020; Kreysa et al., 2016; MacDonald, 2009; Tessler and Sushelsky, 1978). Interestingly, research indicates that images, such as portraits and photos that mimic eye contact through a direct gaze, can actually evoke similar brain responses to real-life eye contact (Kesner et al., 2018), making them important artefacts to examine. In real life interactions, eye contact can be very important for people living with dementia, for instance, Allan Davis (2015) says that: ‘My attention span and ability to pay attention are not as good as they once were. Please make eye contact with me before you start talking. A nice smile always gets my attention.’

Relatedly, humans draw on our physical experiences with the world to help us to communicate less tangible aspects. Within this, vision is metaphorically linked to cognition, at least in a Western context (Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 2008). For instance, we talk about seeing one another’s viewpoints when we communicate what we’re thinking and feeling – and you can hopefully see the point I’m making here, rather than it being about as clear as mud… As Schweda (2019: p. 4) has argued: when truth is conceptualised in terms of light (e.g., not telling someone the truth is “keeping them in the dark”) and cognition is conceptualised as visual perception, ‘declining cognition for conditions such as dementia can be symbolized as the impairment of this visual perception’, often by meteorological phenomena such as fog, rain and darkness. Such a metaphor can be useful; for instance, Keith Oliver (2015) says that: ‘whilst it’s easy [to] exaggerate using metaphors, I think it can be useful to give people insight into my world of living with dementia. One metaphor I use is about the fog. Which on bad days it’s like living in a fog, on good days – and there are more good days than bad – the sun shines and life is much clearer.’

Amongst humans, then, eyes and vision are important tools both for relationship building and communicating about our subjective experiences (or inner worlds). In a society where artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly evolving and increasingly being integrated into images and texts, we were interested in how AI might in turn represent people living with dementia – and because that’s such a big question for a little blog post, today, for the reasons mentioned above, I’m just focusing on eyes, gaze and vision.

Generating images and character descriptions with AI

In our research, we used Stable Diffusion (version 1.4) to generate images. Stable Diffusion is a deep learning model that has been trained on a huge dataset of captioned images so that it can generate images in a range of styles in response to the user’s textual prompts. We used the text prompt “dementia” to generate a total of 171 images by using all of the available image generation models and the three main formats: landscape, portrait and square.

To generate character descriptions of people with dementia, we used Sudowrite, which advertises itself as ‘the non-judgemental, unexpectedly creative AI writing tool that sounds like you, not a robot’ (Sudowrite, 2024). Sudowrite is an AI writing programme based on GPT-3 and GPT-4 that is aimed at fiction writers and ‘generates text by guessing what’s most likely to come next, one word at a time’ – these guesses are based on its training data (Sudowrite 2024). In this study, we used Sudowrite’s “describe” function, which categorises its output according to the five senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, smell) and metaphors. We used four distinct textual prompts that considered two genders and the perspectives of a character with (‘I am a (wo)man with dementia’) and without dementia (‘I saw a (wo)man with dementia’) to generate a total of 52 separate character descriptions, totalling 22,638 words.

What did we find?

1. Fogginess: Dementia is associated with impaired vision.

The metaphorical representation of dementia as impaired vision was surprisingly prevalent in our character descriptions. The experience of characters with dementia is one of a world of fog, blurriness, dimness and greyscale, for example:

‘My eyes are dimmed with fog. […] My surroundings are grey, colors have long since left me. A world of grey faces and black and white is all I know.’

‘I see the world as blurry, like an old film shot inside a rain cloud. Colors become muted and indistinct, objects lose their sharpness. It is a drab world with little contrast.’

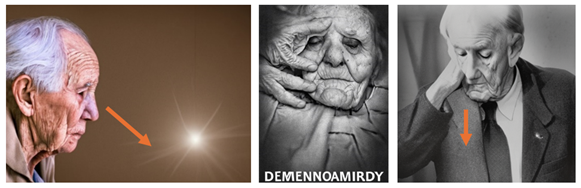

Interestingly, this lack of colour can also be seen visually. Indeed, 56 of the 171 images are in greyscale, and many more are predominately greyscale, or otherwise use a limited colour palette of blues, beiges and shadows when representing the person with dementia (see Figure 1).

2. Both AI outputs establish social distance from people with dementia.

Importantly, 107 of the 130 images that we coded as showing people showed individuals, usually not looking at viewers and instead either looking off camera (most frequently downwards) or seeming to have their eyes closed. This encourages viewers to observe these individuals rather than seek to connect, which helps to create a sense of social distance between the represented individuals and viewers.

3. Both AI outputs associate people with dementia with living death.

While eyes can be positioned as a window to inner emotional states (usually of fear or suffering, as with ‘His face looked right, but his eyes did not. They showed fear and pain within’), oftentimes, eyes are instead used to attribute an emptiness to people with dementia:

‘Her eyes are empty windows, a blank gaze, like a doll’s’

‘The woman is a ghost of her former self. […] Most unsettling are her eyes. They look at something that isn’t there. One sees only blankness’

Associated with this sense of emptiness, or blankness, is an inhumanity, as exemplified by the comparisons to inanimate objects (a doll) and spirits (ghost) above. In the images, this sense of deathliness is instead conveyed through the visual metaphor of bare trees, which I’ve unpacked further in a previous blog post. Arguably, as well as being related to the impaired vision metaphor, the trend of using a drab colour palette (Figure 1) adds to this sense of lifelessness.

So what?

Although there some examples of social connection (e.g., ‘‘When she saw me, her eyes lit up with surprise and warmth’) and colour in the AI-generated representations, these were few and far between. The tropes therefore indicate an overall imbalance in the representation of people living with dementia that foregrounds social distance, blankness, deathliness and a grey, foggy and dark world. Yet, to return to Keith Oliver’s use of the fog metaphor, although ‘on bad days it’s like living in a fog’, there can also be good (or at least better) days, where ‘the sun shines and life is much clearer’. Our dataset would certainly suggest that more sunshine and colour is needed when training AI to represent dementia. However, thinking of the recent, highly controversial Alzheimer’s Society advert (which claims that ‘With dementia, you don’t just die once. You die again, and again, and again’), a similarly critical eye needs to also be turned to human-produced representations, too. Dementia is a diverse and complex condition, and people’s experiences are similarly diverse and multifaceted. Conversations need to be had (again, and again, and again) about how to better reflect this breadth in public discourses moving forward.

Interested in reading more?

Putland, E., Chikodzore-Paterson, C. and Brookes, G. (2023). ‘Artificial intelligence and visual discourse: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of AI-generated images of “Dementia”’, Social Semiotics, 0(0): https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2023.2290555

Putland, E., Chikodzore-Paterson, C. and Brookes, G. (Forthcoming). ‘”We no longer recognized her as a human being”: A Critical Discourse Analysis of AI-generated character descriptions of men and women with dementia’.

References

Davis, A. (2015). ‘Thought for the week No. 6: “Please make eye contact with me before you start talking”’, Dementia Diaries. https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/2164/thought-for-the-week-no-6-my-attention-span-and-ability-to-pay-attention-are-not-as-good-as-they-once-were-please-make-eye-contact-with-me-before-you-start-talking/?highlight=eye

Ibarretxe-Antuñano, I. (2008). ‘Vision Metaphors for the Intellect: Are they Really Cross-Linguistic?’, Atlantis, 30(1): pp. 15-33.

Jarrett, C. (2019). ‘Why meeting another’s gaze is so powerful’, BBC Future. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190108-why-meeting-anothers-gaze-is-so-powerful

Jongerius, C., Hessels, R. Romijn, J., Smets, E. and Hillen, M. (2020). ‘The Measurement of Eye Contact

in Human Interactions: A Scoping Review’, Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44: pp. 363–389.

Kesner, L., Grygarováa, D., Fajnerová, I., Lukavskýa, J., Nekovářová, T., Tintěra, J., Zaytseva,

Y., Horáček, J. (2019). ‘Perception of direct vs. averted gaze in portrait paintings: An fMRI and eyetracking study’, Brain and Cognition, 125: pp. 88-99.

Kreysa, H., Kessler, L. and Schweinberger, S. (2016). ‘Direct Speaker Gaze Promotes Trust in Truth-Ambiguous Statements’, PLOS One 11(9): pp. 1-15.

MacDonald, K. (2009). ‘Patient-Clinician Eye Contact: Social Neuroscience and Art of Clinical Engagement’, Postgraduate Medicine, 121(4): pp. 136-144.

Oliver, K. (2015). ‘“On bad days it’s like living in a fog”’, Dementia Diaries. https://dementiadiaries.org/entry/1208/on-bad-days-its-like-living-in-a-fog/

Sudowrite (2024) Sudowrite homepage. https://www.sudowrite.com/.

Tessler, R. and Sushelsky, L. (1978). ‘Effects of eye contact and social status on the perception of a job applicant in an employment interviewing situation’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 13(3): pp.338-347.