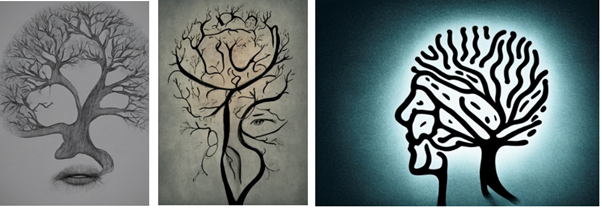

The image above was generated using the textual prompt “dementia” in the text-to-image generation programme, Stable Diffusion (version 1.4).

On Friday 8th of December, our team had the pleasure of contributing to the 8th Global China Dialogue, with the theme of ‘Governance for Global Health’ at the British Academy. While this topic was actually planned before the pandemic, its legacy was certainly felt throughout the day. As one of the speakers noted, in an increasingly interconnected world, a virus can spread with incredible speed, but so too can communication (and conversely, misinformation). Having constructive dialogues between a range of stakeholders is essential to moving forward in a more equitable and responsive manner.

As part of the ‘Communicating to Improve Global Health’ panel, we presented some of our Public Discourse of Dementia project research alongside panellists discussing vaccine hesitancy, traditional Chinese medicine, globalisation and supporting health engagement and co-creation. We used our time to give a whistle-stop tour of two of the contexts in which we’re currently exploring communication about dementia: UK newspapers and AI generated images. Here, I wanted to briefly talk about metaphor and dementia in these two contexts – and if you’re interested in reading about our analysis beyond this, I’ve provided links to both of our papers at the end of this blog post.

Metaphor is essentially when ‘we talk and, potentially, think about something in terms of something else’ (Semino 2008, p. 1). For instance, if life is envisioned as a book, then starting a new stage of your life is “starting a new chapter”. Metaphors can be especially useful for communicating about and understanding more complex, intangible and subjective aspects of the world, including chronic health conditions, such as dementia. Metaphors also perform an important role in framing a topic, since certain aspects will be foregrounded, while other aspects are backgrounded or ignored. Researching the types of metaphors used and their implications therefore becomes very important as part of broader drive to better understand how dementia is communicated and address the stigma surrounding dementia.

Metaphors in the news

Gavin recently analysed 6,751 articles from UK newspapers that discuss dementia over ten years (2010-2019). Taking a corpus-based approach, he identified a range of metaphors that framed different aspects of dementia, namely: prevalence, causes, symptoms and prognosis, lived experience, and responses. Amongst many findings, Gavin showed that metaphorical representations of dementia symptoms and prognoses often humanise dementia as intentionally inflicting violence on those diagnosed with it (e.g., through word choices such as ‘savage’, ‘heartless’ and ’brutally’). Memory, cognitive function and even personhood are all framed as things that are stolen by dementia, for example:

‘Victims of dementia, which robs sufferers of their memory, rely on social care as drugs are unable to slow the progression of the incurable disease.’ (Mail 2017)

In terms of its prognosis, the newspapers frequently foreground a fatalistic view of dementia, framing it as a murderer that kills those diagnosed with it:

‘DEMENTIA kills more Brits than any other illness, new figures show.’ (Sun 2017)

Such a framing obscures the fact that people may live and die with this chronic degenerative condition but they do not die of it (in fact, the most common cause of death in people with dementia is actually pneumonia). A report by Public Health England suggests three explanations for these new figures of dementia-related deaths: (1) an actual increase of people dying with dementia because people are living longer, (2) greater awareness and understanding of dementia, alongside key policy changes to encourage more frequently recording the condition, and (3) changes in coding practices on death certificates (Khera-Butler 2016).

Alternatively, dementia’s symptoms are also metaphorically portrayed as the ‘loss’ of memory and cognitive function. In societies that overly prioritise high cognitive function, alongside traits such as independence, productivity and rationality (Post 2000), such losses have been framed as indicators of a loss of self for people with dementia and a ‘social death’ (Sweeting and Gilhooly 1997). While the notion of memory loss is a conventional metaphor for dementia, it is worth noting that rather than making dementia the active agent, people with dementia are given agency in many of the newspaper examples by being framed as having metaphorically lost the particular functions under focus, as with:

‘Many people with dementia gradually lose their ability to walk and perform simple tasks as their condition progresses.’ (Mirror 2016)

Metaphors in AI-generated images

Just as the invention of the printing press revolutionised the sharing of information through printed media, today, generative artificial intelligence (or AI) is increasingly influencing communication. One area where this is the case is AI text-to-image generation, where a user gives a textual prompt and AI generates images in response, having been trained on a huge database of captioned images. Text-to-image generation is an increasingly accessible and popular way of generating visuals, including for professional text producers, with stock image banks like Shutterstock now offering users the option to generate their own images as well as to buy pre-made ones. However, since AI is often trained on biased data, research indicates that AI outputs can not only reflect but actually amplify pre-existing human stereotypes.

With this in mind, it’s worth asking: how might a complex and often misrepresented condition like dementia be visualised by AI generated images, based on the AI’s interpretation of human-produced training data? To explore this, we worked with our colleague, Chris Chikodzore-Paterson, to generate 171 images using the text prompt “dementia” on the popular open-source AI text-to-image generation programme Stable Diffusion (version 1.4). We then conducted a Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis to consider patterns in how the images depicted dementia, and the wider discourses that these related to. As Figure 1 shows, a key metaphor that we identified in the images was that the brain of someone with dementia is a tree that has lost its leaves:

The tree, a ‘symbol of life and image of seasonal change’, is popularly associated with the brain (Zimmermann 2017, 80), and the brain of someone living with dementia is therefore often metaphorically envisioned as a tree losing or having lost its leaves, in which the leaves may represent brain cells, memories or personal qualities (Ang, Yeo, and Koran 2023; Putland 2022; Zimmermann 2017). While such a metaphor can be interpreted as a useful way of explaining the complexities of brain changes and symptom progression with dementia, it can also be considered to be stigmatising (Putland 2022). Notably, having lost leaves (which may represent brain cells, memories, personal qualities etc.) perpetuates the conventionalised metaphor mentioned above that dementia entails a ‘loss’ of memory and cognitive function – and perhaps even selfhood – which risks implying that people with dementia are incomplete and (both literally and metaphorically) lesser persons. The bare branches situate these individuals as being in winter, which, when applied to the lifecycle, is widely associated with bleakness and death (Lakoff and Turner 2009), something further reinforced by the cold and dull colour palette of these images (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2002). This reiterates the metaphorical positioning of dementia as a social or physical ‘death sentence’ (Castaño 2020), which subsequently ignores the new experiences and growth that people with dementia can experience (O’Connor et al. 2022).

To summarise, metaphors can be a very constructive strategy for communicating about dementia in ways that help to make this very complex condition more comprehendible. However, it is vital that we critically engage with the implications of the metaphors that are used, since all metaphors frame social issues in ways that foreground certain ideologies and aspects above others. Linguistic and visual choices need to be accurate, sensitive and not obscure the real-life contexts in which health issues like dementia are lived and experienced. This is something that the Public Discourses of Dementia project is trying to support, including through the development of evidence-based, linguistically sensitive guidelines and training.

If you’re interested in reading about these topics more fully, please see our recent publications:

Gavin Brookes. 2023. ‘Killer, Thief or Companion? A Corpus-Based Study of Dementia Metaphors in UK Tabloids’, Metaphor and Symbol 38(3): 213-230. DOI: 10.1080/10926488.2022.2142472. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10926488.2022.2142472.

Emma Putland, Chris Chikodzore-Paterson and Gavin Brookes. 2023. ‘Artificial intelligence and visual discourse: a multimodal critical discourse analysis of AI-generated images of “Dementia”’, Social Semiotics, DOI: 10.1080/10350330.2023.2290555. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10350330.2023.2290555.

References

Ang, Pei Soo, Siang Lee Yeo, and Leela Koran. 2023. ‘Advocating for a Dementia-Inclusive Visual Communication’. Dementia, 22(3): 628-645. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012231155979.

Castaño, Emilia. 2020. ‘Discourse Analysis as a Tool for Uncovering the Lived Experience of Dementia: Metaphor Framing and Well-Being in Early-Onset Dementia Narratives’. Discourse & Communication 14(2): 115–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481319890385.

Khera-Butler, T. (2016). Data Analysis Report: Dying with Dementia. London: Public Health England.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo Van Leeuwen. 2002. ‘Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour’. Visual Communication 1(3): 343–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/147035720200100306.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Turner. 2009. More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O’Connor, Deborah, Mariko Sakamoto, Kishore Seetharaman, Habib Chaudhury, and Alison Phinney. 2022. ‘Conceptualizing Citizenship in Dementia: A Scoping Review of the Literature’. Dementia 21(7): 2310–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221111014.

Post, Stephen. 2000. ‘The Concept of Alzheimer Disease in a Hypercognitive Society.’ In Concepts of Alzheimer Disease: Biological, Clinical, and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Peter Whitehouse, Konrad Maurer, and Jesse Ballenger, 245–255. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Putland, Emma. 2022. ‘The (in)Accuracies of Floating Leaves: How People with Varying Experiences of Dementia Differently Position the Same Visual Metaphor’. Dementia 21(5): 1471–1487. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211072507.

Semino, Elena. 2008. Metaphor in Discourse. Cambridge: University Press.

Sweeting, Helen, and Mary Gilhooly. 1997. ‘Dementia and the phenomenon of social death’. Sociology of Health & Illness 19(1): 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00017.x.

Zimmermann, Martina. 2017. ‘Alzheimer’s Disease Metaphors as Mirror and Lens to the Stigma of Dementia’. Literature and Medicine 35 (1): 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2017.0003.