Summary

After attending the 2022 conference of the British Association for Applied Linguistics, attendee Emma Putland reflects on some of the key themes and thinking points to emerge from the conference for her, orienting around two questions asked by the keynote speaker, Khawla Badwan: “What matters in Applied Linguistics? And who determines what matters?”

The two questions that make up this title were asked during Khawla Badwan’s fantastic plenary at the 2022 conference of the British Association for Applied Linguistics (BAAL), which this year was hosted by Queen’s University Belfast with the theme of ‘Innovation and Social Justice in Applied Linguistics’. As part of this, Badwan encouraged the audience to think about who was/is not considered to be fully ‘human’ (due to factors such as age, class, race, gender, religion, sexual orientation or disability) and how these social ideologies still inform contemporary linguistic theories and approaches to research. This widespread injustice harms many people, as well as the field of linguistics which, due to long-standing exclusionary practices, is grounded in only a partial knowledge of the world. Clearly, significant change is needed.

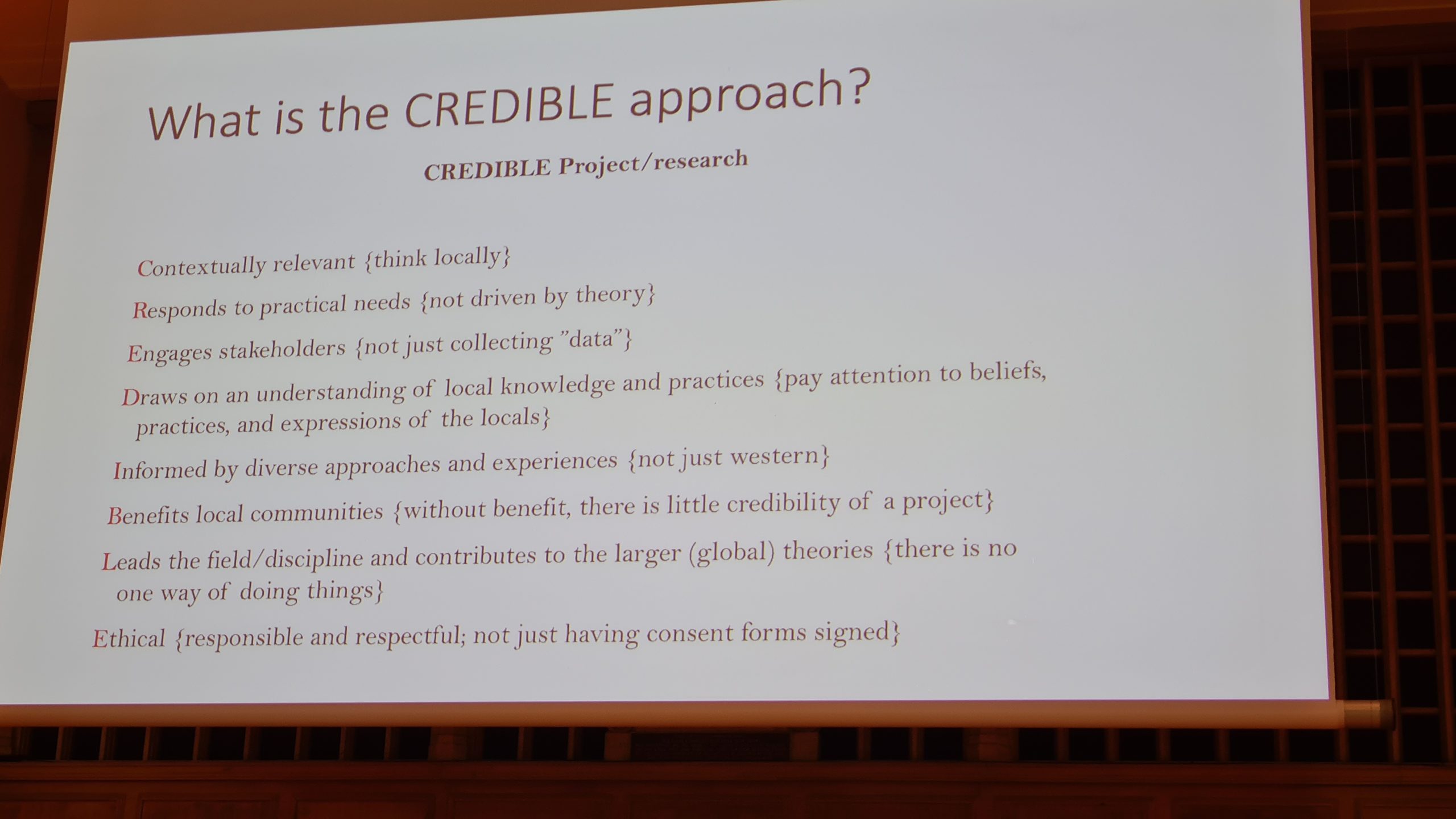

In another plenary, Ahmar Mahboob (A.K.A. Sunny Boy Mahboob) discussed an approach that could help with such a transition, namely the CREDIBLE approach:

I personally found this to be a useful roadmap for considering “what matters” in current and future projects. As part of this, I enjoyed hearing about research that orients around creating tangible resources, for instance, a multilingual picture book that engages with social issues such as migrating to a new culture, and a Master’s dissertation that is formatted as a ‘How-to’ guide for creating such a resource. There are countless possibilities when we challenge the traditional format of research and prioritise benefitting specific communities (beyond researchers) in research dissemination…

Nonetheless, conferences remain a fantastic place to share ideas and learn from each other. With countless parallel sessions, there were many talks that I wanted to attend yet could not, so I can only speak to the ones that I was able to see. Within the Health and Science Communication SIG track, for example, I learned about Kate Sayers’ research into a more intersectional and thus inclusive study of linguistic markers of low mood, alongside the complexities within emotion discourses of end-of-life workers in Hong Kong (David Edmonds and Olga Zayts), health inequalities in communication during Covid-19 (Erika Kalocsányiová, Ryan Essex, Vanessa Fortune), and how representations of schizophrenia have changed over time in the British Press (James Balfour). Also in this track, Emma McClaughlin’s fascinating talk explored how 1,089 UK residents responded to different types of public health messaging during Covid-19, demonstrating how corpus-assisted linguistic analysis within a community-focused approach can recognise and help address issues in public health communication.

The Colloquium ‘Applied Linguistics research landscape in the post-Covid world’ returned to Badwan’s questions about what matters and who determines this, with a call to challenge the overemphasis on the English language to explore alternative theories of knowledge (Niall Curry) and advocate for justice through interdisciplinarity, community collaboration and greater institutional inclusivity. A common theme throughout this conference, then, is the importance of seeking out ways to consult and collaborate with people who do not normally get to have a say in the “research agenda”. In the context of the Public Discourses of Dementia Project, I’m excited to be part of a dialogue with people who have dementia, as well as other stakeholders, such as charity leads and journalists. Too often, there’s no or little dialogue, as highlighted in another conference presentation about combining the perspectives of a linguist and journalist to analyse newspapers, by Elaine Vaughan and Fergal Quinn. As a field that studies language, we desperately need to better attend to the conversations that we’re having in relation to our research – and with who. Outside of a linguistics context, I’m excited to see people with dementia increasingly taking charge of the research agenda, as seen by the Dementia Enquirers – this seems to be an excellent source of inspiration and learning for more diverse, collaborative and experience-led ways forward in research.

When we are involved in these kinds of conversations and collaborations, what should we consider? Across the conference, there were many interesting discussions relating to the position of the researcher. For example, Hannah Valenzuela reflected on how teenage participants brought their own agendas to their interactions and differently positioned Valenzuela as a helpful resource, whether as a source of information or as an advocate, which created a more collaborative research journey. Foregrounding what is usually behind-the-scenes, Piotr Węgorowski considered consent procedures, asking: how easy is it to say no, and how will we know? Talks such as these made me question exactly how different people interpret our research interactions, and how I might be more cognisant and adapt my practices accordingly.

Within researcher positionality, we need to consider our approach to the concept of communication itself. As Badwan eloquently proposed, we need to stop treating human participants as “angels”, i.e., as minds without bodies. I am as guilty of this as anyone else. I firmly believe in the importance of acknowledging embodiment (that we exist as bodies, not just minds) and yet, when it comes down to it, so much of my research relies simply on what people say. I need to think about how I can reconcile my linguistic theories and methodologies with the fact that communicating experience is about so much more than what is said. If you have any ideas for how to do this, do let me know!

I’ll end by broadening the questions asked by this conference. What matters in research? And who gets to decide? How can researchers change the status quo and what might be the benefits of this?

In a nutshell: what’s next?