Gifting the Womb: The UK's First Uterus Transplant

By Dr Laura O’Donovan, published 10th November 2023

Last week’s National Fertility Awareness Week highlighted the challenges that 1 in 6 people in the UK face when trying to have children. This blog focuses on uterus transplantation: a novel method of reproduction that hit the headlines this summer when the first transplant took place in the UK.

After decades of research into the concept of uterus transplantation (UTx), the UK’s first transplant, funded by charity Womb Transplant UK, was announced on 23 August 2023. The operation, which took place earlier this year, was made possible thanks to the recipient’s sister who offered to donate her womb. After an eight-hour surgery to remove the uterus, and a further complex nine-hour surgery to transplant the organ, the procedure was complete. Now, six months on, the recipient is having periods and embryo transfer is expected to take place this autumn.

The what and the why

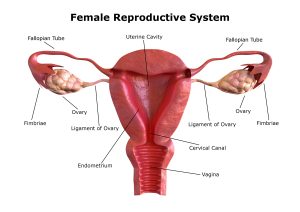

This hybrid reproductive-transplant treatment combines IVF with transplantation of the uterus (also including the cervix, a vaginal cuff, blood vessels and surrounding ligamentous tissues) to enable women* with absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI) to have children. AUFI is a condition characterised by either the absence of the uterus or the presence of an anatomically or physiologically dysfunctional one, and the cause may be congenital (e.g. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome), or acquired (hysterectomy for gynaecological cancer or other conditions causing anatomical or functional abnormalities). The procedure is currently being performed in genetic females only, though there has been some discussion among the UTx community about the feasibility and desirability of the procedure in trans women.

This hybrid reproductive-transplant treatment combines IVF with transplantation of the uterus (also including the cervix, a vaginal cuff, blood vessels and surrounding ligamentous tissues) to enable women* with absolute uterine factor infertility (AUFI) to have children. AUFI is a condition characterised by either the absence of the uterus or the presence of an anatomically or physiologically dysfunctional one, and the cause may be congenital (e.g. Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome), or acquired (hysterectomy for gynaecological cancer or other conditions causing anatomical or functional abnormalities). The procedure is currently being performed in genetic females only, though there has been some discussion among the UTx community about the feasibility and desirability of the procedure in trans women.

Notably, this transplant is not intended to be permanent. The graft is typically removed after childbearing is complete to avoid the continued need for immunosuppression. Research protocols and general recommendations are that the graft should be removed within 5-7 years. However, there may be medical reasons (rejection, graft failure, pregnancy related etc.) to remove the graft sooner.

This novel surgery represents a huge advance in the field of reproduction. Where well-established techniques like IVF and intrauterine insemination can help those who are struggling to conceive, UTx offers hope to those who are unable to conceive and gestate. Before the advent of UTx, for women who were born without a uterus (like the UK’s first recipient), or those who were required to have their uteruses removed, the only options for family-building were surrogacy or adoption. While both offer legitimate ways to become a parent, as I have argued elsewhere, UTx is ‘experientially unique’, enabling recipients to have children as a result of their own pregnancies. Unlike adoption and surrogacy, UTx can provide biological, social and, importantly, legal parenthood (in English law the woman that gives birth is the legal mother of the child) – something which may be viewed as both desirable and valuable by those with AUFI.

Described as a ‘massive success’ by Mr Richard Smith, who co-leads the UK team, and as ‘the dawn of a new era’ in fertility by Dr Raj Mathur, Chair of the British Fertility Society, the public and media reaction to news of the surgery has been largely positive. However, while we might celebrate this medical achievement and the hope it brings to those with AUFI, it is important that we also remain attentive to the ethical and policy issues it raises.

How safe is UTx?

Foremost among concerns about this procedure are worries about the risks involved. This includes not only the physical and psychological risks posed to the recipient, but also the risks posed to living donors and the developing fetus/future child. UTx involves major complex surgery for both the recipient and living donor. Clearly, there is a risk of defective consent (e.g. induced, coerced, or insufficiently informed consent) in addition to the risk of surgical and post-operative complications.

The recipient and any developing fetus will also be exposed to the risk of immunosuppression medication (including the possible risk of post-transplant malignancy, increased risk of infection and high blood pressure for recipients, and a possible risk of pre-term birth and low birth weight for fetuses). For donors, there is also the risk of donor regret or donor guilt if the transplant fails. Regarding children, so far current data shows that children born as a result of UTx do not have any identified malformation or organ dysfunction. That said, longer term follow-up and data on a larger number of children are needed to ensure effective safety monitoring.

The risk-benefit calculation is a careful balance that requires ongoing assessment as more operations are performed and more data is gathered worldwide. This is why it is important that robust counselling and consent procedures are in place to ensure recipients and donors are able to provide valid informed consent. Long-term safety monitoring is also key, and the data registry, established by the International Society for Uterus Transplantation, has an important role to play in this regard.

Who can access UTx?

Access to UTx may be an issue moving forward given the costs involved. For instance, the recent UK transplant cost a total of £25,000 and this did not include the cost of IVF to create embryos, or the time of the medical staff involved in the procedure. In England, there already exists a postcode lottery of funding for fertility treatment with different Integrated Care Boards around the country offering different amounts of IVF treatment subject to different eligibility criteria. On the face of it, public funding for UTx may be justified in the interests of patient autonomy and wellbeing if the psychological harms associated with involuntary infertility are taken seriously, as they should be. However, this will be a difficult decision for NHS Commissioners to make given that they manage finite budgets and will need to decide where on the list of priorities UTx should fall.

Access to UTx may be an issue moving forward given the costs involved. For instance, the recent UK transplant cost a total of £25,000 and this did not include the cost of IVF to create embryos, or the time of the medical staff involved in the procedure. In England, there already exists a postcode lottery of funding for fertility treatment with different Integrated Care Boards around the country offering different amounts of IVF treatment subject to different eligibility criteria. On the face of it, public funding for UTx may be justified in the interests of patient autonomy and wellbeing if the psychological harms associated with involuntary infertility are taken seriously, as they should be. However, this will be a difficult decision for NHS Commissioners to make given that they manage finite budgets and will need to decide where on the list of priorities UTx should fall.

Another access issue concerns whether patient eligibility criteria should be expanded and, as experience in UTx continues to grow, this is something that will need to be considered. This also includes the question of possible expansion to trans women. While there are different hormonal and anatomical considerations that need thinking through, there may be equality-based reasons for considering UTx in trans women. In the UK, gender reassignment is a protected characteristic under the Equality Act 2010. This means that assuming the procedure is technically feasible, safe and effective in trans women then they could not be refused treatment on the basis of their gender identity.

Does UTx devalue other forms of parenthood?

Another key concern about UTx is the worry that it may serve to reinforce and legitimise pronatalist, essentialist and geneticist norms and devalue other forms of parenthood. We are right to be concerned about the social messaging surrounding scientific pursuits to ‘treat’ particular medical conditions. It is possible, for instance, that pervasive and gendered social pressures may not only shape women’s decisions to pursue UTx but may also lead them to underappreciate the risk associated with it. To reduce these risks, educative and other policy initiatives promoting the value of alternative options, including childlessness, ought to be pursued at state level.

It is both advisable and desirable to be mindful of the contextual factors that might affect the autonomous nature of a decision to pursue UTx. However, a preoccupation with envisioned social harms (the effect of which it is not possible to quantify) risks minimising the importance of supporting those with AUFI to be self-determining when it comes to family-building. Furthermore, while it may be that the desire for UTx is felt more forcefully as a result of current social norms, a desire for parenthood may arise even in the absence of pronatalist ideology. I’m of the view that a commitment to dismantling problematic social norms, regarding the role of women’s bodies in reproduction, can be coextensive with a commitment to ensuring maximum respect for the reproductive autonomy of those with AUFI via the provision, even the public provision, of UTx.

* Eligibility criteria for the UK UTx programme stipulates that the recipient must be a genetic female. Some genetic females with AUFI who may wish to pursue UTx may not identify as women, however, it seems reasonable to assume that the majority do.

Other Posts

- “The genetics bomb could be a disaster”: Author Simon Mawer on Mendel’s Dwarf

- Spotlight on CRISPR-Cas9

- Exhibition Review: Genetic Automata

- A Look Back at 2023

- Explainer: Human Stem Cell Based Embryo Models

- Is it time to revisit the 14-day rule?

- Discipline Hopping: UK Law and Emerging Reproductive Technologies

- Reflections: A Look Back at the First Year of the Project

- Book Review – Eve: The Disobedient Future of Birth

- Ectogenesis: A Retrospective