This is the third in a new mini-series of posts about our lovely volunteers on Zooniverse. The spotlight pieces will focus on individual volunteers; they will allow us to learn a bit more about what motivates individuals to volunteer to transcribe Davy’s notebooks and what people’s particular interests in Davy might be.

Volunteer in the spotlight: @TEHark

1. What interests you about the project?

I have an undergraduate degree in Classical Languages and a graduate degree in Latin and Secondary Education, so I’ve worked quite a bit with old texts. While I never delved too much into reading manuscripts, I sometimes had to examine multiple potential readings, contend with mangled lines, and so on. Sometimes, if we’re very, very lucky, we have reliable accounts of what an author, for whatever reason, did not tell us in any given work. This project gives us the chance to do that with Humphry Davy.

2. Why are you enjoying it?

Deciphering old and sometimes messy handwriting is a kind of puzzle, and, combined with the interesting subject matter, I jumped in with both feet, as it were. They’re also a kind of window into the past. Beyond the writing, it’s neat to see a sketch, a smudge from a hand, a message to his assistants, or even damage from the occasional lab accident. Davy’s notebooks also show the broad range of his interests. I’ve transcribed notes, short stories, poetry, philosophy, travel, and, of course, experiments. Every page can be different, and occasionally even surprising!

3. Do you have any particular interest in Davy?

I got into the project because I recognized his name – primarily, I think, from his nitrous oxide experiments, with a vaguer sense of his work isolating certain elements. I have a long-standing interest in science and the history of science, and how we established the knowledge we take for granted today.

4. Are sciences and arts ‘separate’?

They are not as separate as we sometimes think they are! Davy excelled in communicating his work to various audiences, which is itself a kind of art. The arts can also be a way to imagine or consider what could be possible in science, not just what is possible right now.

5. What have you learned about Davy since joining the project?

It makes perfect sense now but seeing how Davy interacted with scientists and writers we still know today, both in the UK and across Europe, is really neat. I wasn’t aware of his connection to Michael Faraday, for instance, nor of him knowing Sir Walter Scott, Coleridge, or Wordsworth. I also learned that Davy did some research in geology, which was a relatively new field at the time.

6. Do you have any favourite pages of Davy’s notebooks?

There are numerous pages that I remember well, and it’s hard to choose!

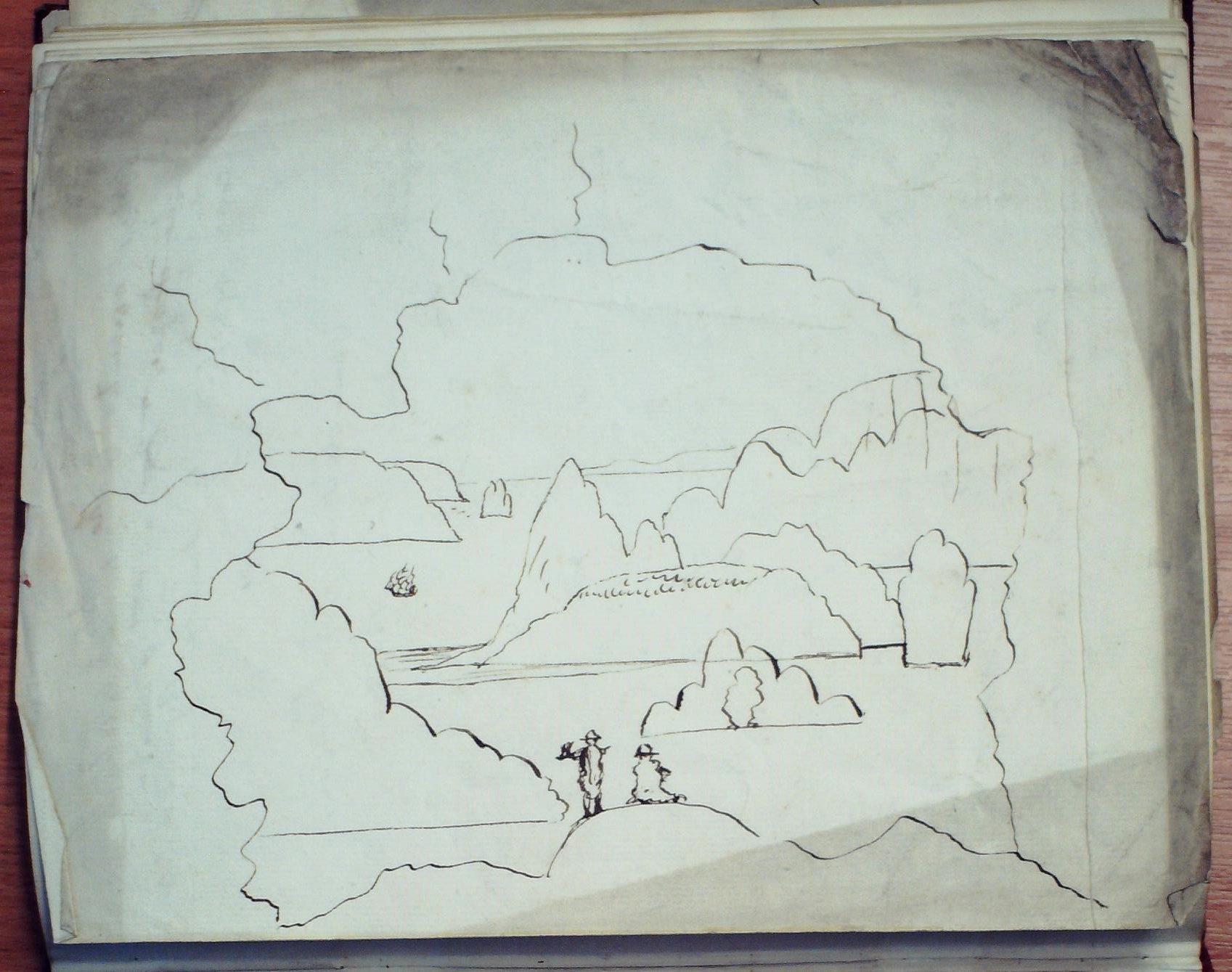

In RI MS HD/22/C, there’s a really nice drawing of what could be a cave somewhere on Cornwall’s coast. The cave frames the scenery in an unusual way, and there are two figures in cloaks and hats in the center. Davy could be quite the artist!

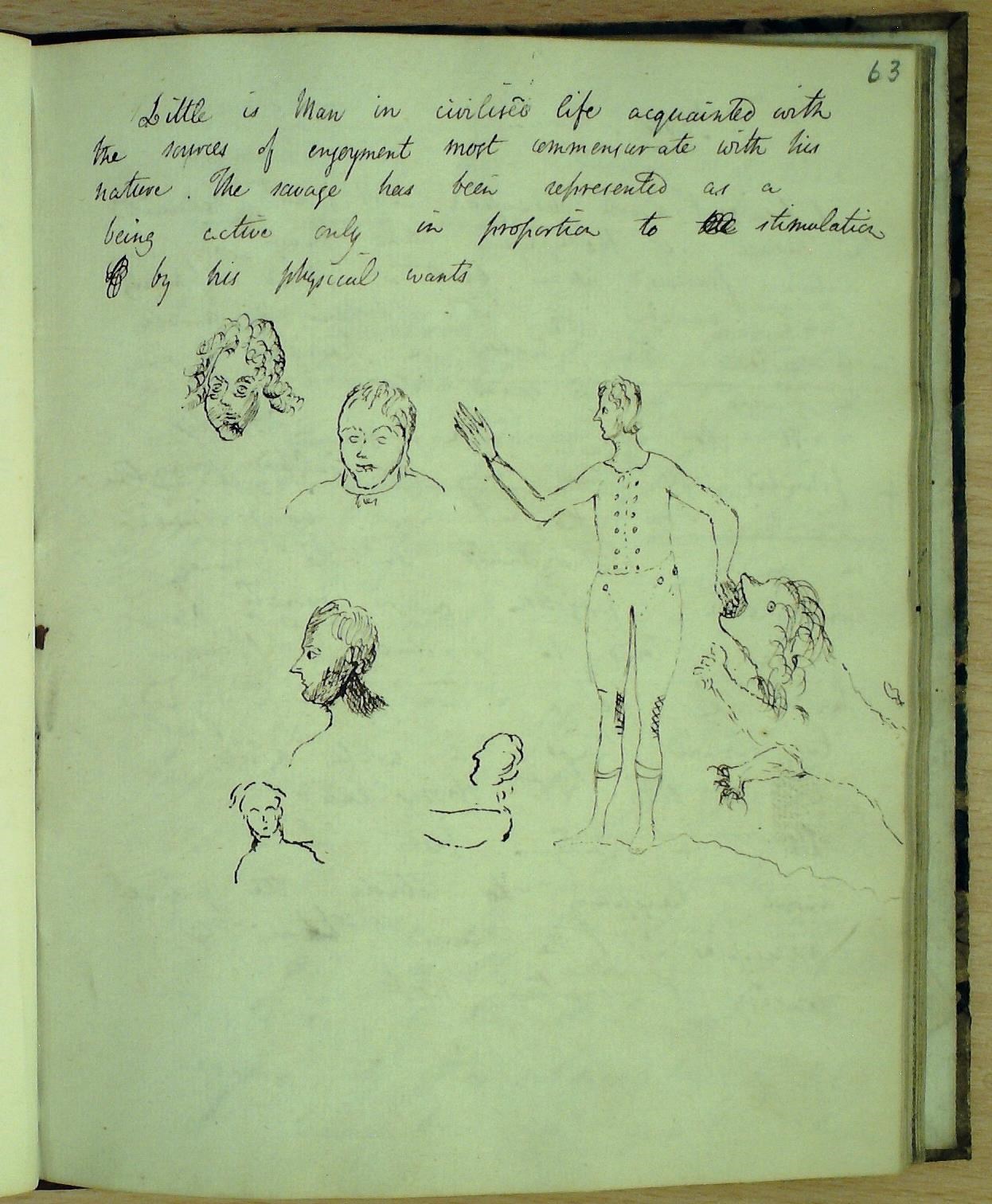

In RI MS HD/15/J, there are some doodles. A lion with a rather heraldic look appears to bite a man’s hand.

In one of the laboratory notebooks (RI MS HD/07), it was really interesting to trace the change from oxymuriatic acid gas to chlorine. It was used a few times after the 1810 Bakerian Lecture, when Davy proposed the name, but then was abandoned, evidently because it wasn’t fully accepted. Only later in the following year did the notebook start using chlorine consistently.

Thank you, @TEHark!

If you’re a Zooniverse volunteer who’d like to be featured, please let us know on Talk, or by e-mail.