As I write, our 1450-strong volunteer transcriber community on Zooniverse has transcribed nineteen full Davy notebooks, with the twentieth to soon follow. This is a tremendous achievement, for which the Davy Notebooks Project team are very grateful. We’ll soon be releasing the third (of nine) tranche of notebooks, which contain notes and sketches from Davy’s geological tour of Ireland (c. 1805-6), material relating to Davy’s highly influential chemical work on the decomposition of the fixed alkalis, and the draft essays ‘On the species of matter’ and ‘Of magnetic action’, interspersed with poetry, philosophy, and fragments of various other kinds.

So far, we’ve encountered textual challenges of different types: difficult or even entirely illegible words (which we’ll take to our next project Advisory Board meeting, to see if any of the experts we’ve assembled to help guide the project can help us to decipher them); densely packed text and text with heavy (usually ink) deletion, making reading difficult or, in some cases, practically impossible; and complex tables of figures and mathematical notation, especially in notebook RI MS HD/21/A, the presence of which has obviously considerably slowed the transcription process for this particular notebook. To every volunteer transcriber who has stuck with this most difficult of notebooks, we send special thanks!

While many of the comments on Talk focus on the textual challenges of working with Davy’s notebooks, there are also a distinct set of material challenges – material as in relating to the physical characteristics of the notebooks – that have emerged since we began the pilot phase of the Davy Notebooks Project in 2019. Working in the way that we are – largely online or otherwise digitally and in relative isolation since the coming of the pandemic – distances us from the material experience of working with manuscripts. As such, I thought it would be fitting to focus on some of the physical aspects of manuscript study, in the hope of better days to come. As there’s nothing quite like sitting down in the archive and attempting to make sense of an especially difficult manuscript page, my specific focus here will be on some of the material challenges we’ve encountered so far.[1]

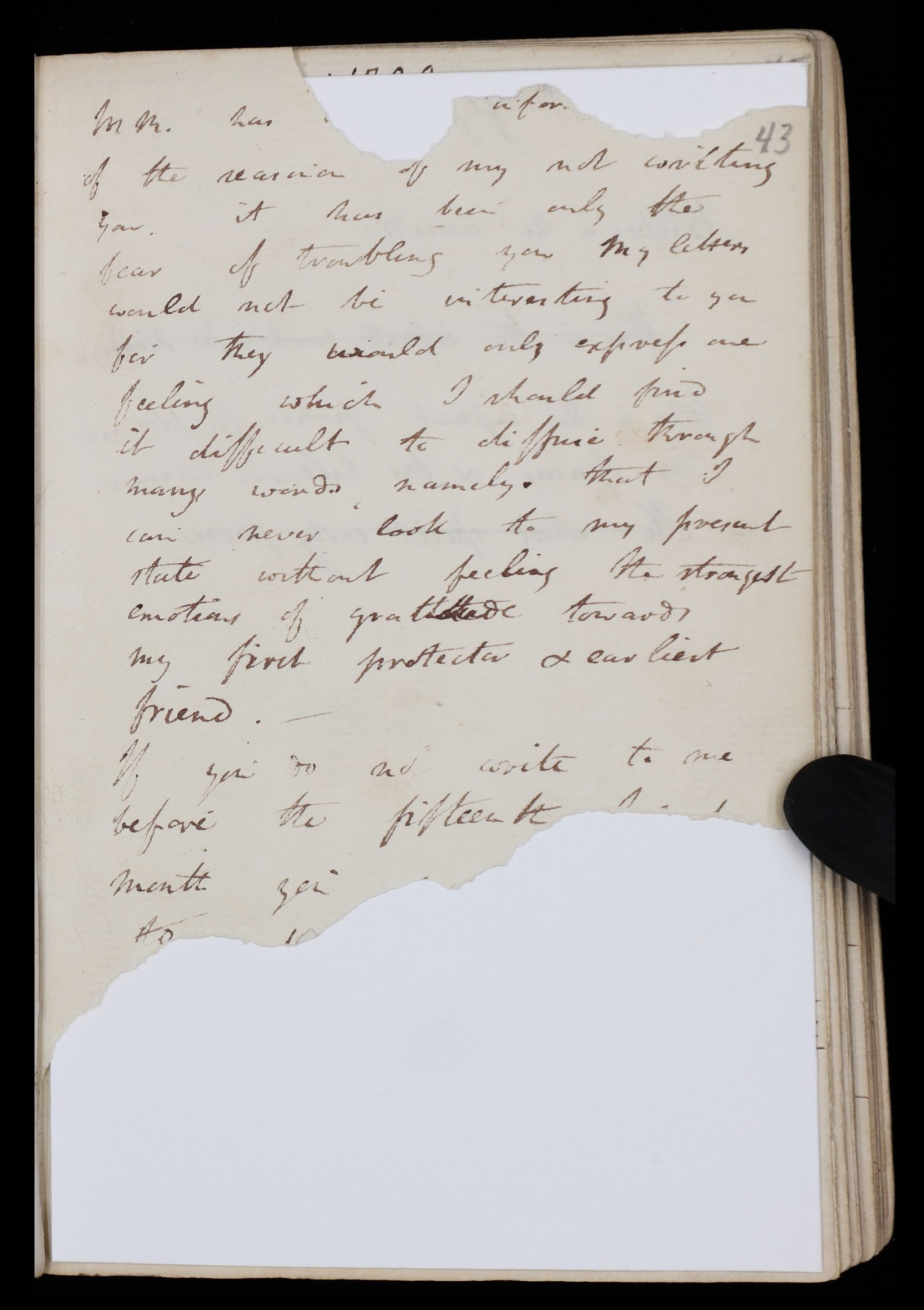

Torn pages, such as this page of notebook 13C, always present something of a puzzle:

RI MS HD/13/C, p. 43 (click to enlarge)

There are two substantial tears on this notebook page, and it’s fair to assume that, as the text is interrupted, both tears happened after Davy entered his text in the notebook. The tears on this page leave us with this text:

M M. has [MS torn] infor[MS torn]

of the reason of my not writing

you. it has been only the

fear of troubling you My letters

would not be interesting to you

for they would only express one

feeling which I should find

it difficult to diffuse through

many words, namely that I

can never look to my present

state without feeling the strongest

emotions of gratitude towards

my first protector & earliest

friend. –

If you do no[?t] write to me

before the fifteenth [MS torn]

month you [MS torn]

to [MS torn]

If we were to approach this page without contextual knowledge (when was this notebook used? Was it Davy’s usual practice to draft what appears to be a letter in his notebooks? Who might Davy’s ‘first protector & earliest friend’ be?), we’d be at something of a loss. As it happens, the phrase ‘first protector & earliest friend’ is key here: Davy uses the same phrase in a letter to John Tonkin, ‘effectively a surrogate father of the Davy family’,[2] dated 12 January 1801, first published in John Davy’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Humphry Davy in 1836.[3] So, the text above, in Davy’s notebook, is likely an early draft of the letter he eventually sent to Tonkin (which is substantively different in other ways; the manuscript of the later letter is now lost). We can surmise that the text at the top of the page, interrupted by the shorter tear, would have read something like ‘M M. has [?already/?lately/?hopefully] informed you of the reason of my not writing you’; the longer tear at the bottom of the page serves as a stark reminder that other crucial details – which, without other draft material to use as corroboration, we cannot even hope to reconstruct with any degree of confidence – are lost forever.[4]

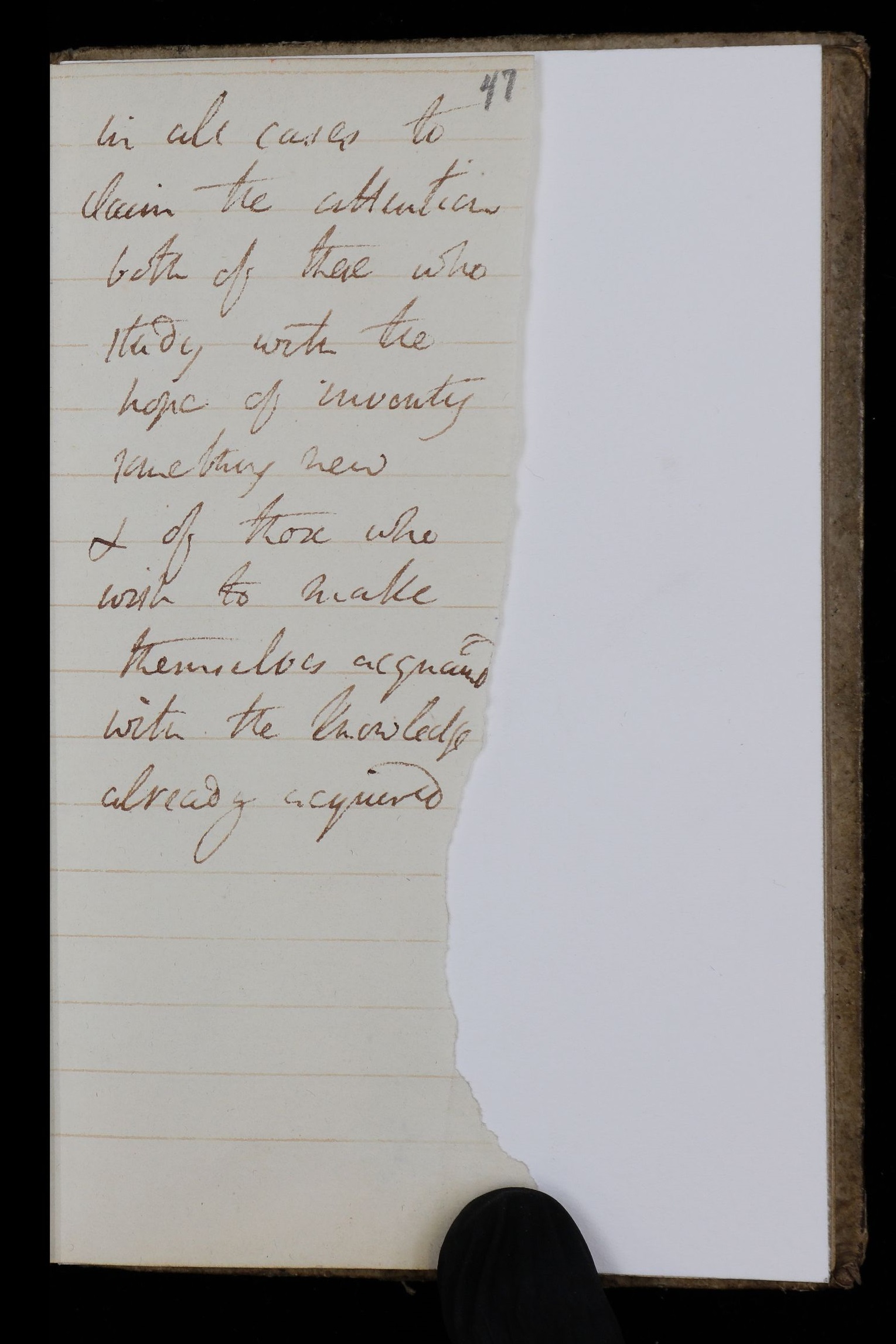

Notebook 15E offers something different – and unusual in Davy’s oeuvre – in terms of the order of text entry and page tearing:

RI MS HD/15/E, p. 47 (click to enlarge)

The text above is entirely legible, and it appears that nothing has been lost as a result of the tear:

in all cases to

claim the attention

both of those who

study with the

hope of inventing

something new

& of those who

wish to make

themselves acquain[te]d

with the knowledge

already acquired

We may therefore safely assume that Davy has written his text on the notebook page after tearing – we can say, with a very high degree of confidence, that he’s working around the tear. This presents much less of a challenge than the previous example, where degrees of speculative reconstruction and cross-referencing were necessary, but still raises a new set of similarly intriguing questions: did Davy tear out the missing part? If so, why might he have done so? Might it be elsewhere, as a fragment, either in the same archive or another archive? I’ll be interested to see whether we encounter any other instances of ‘tearing before writing’ in any of the Davy notebooks we have coming up.

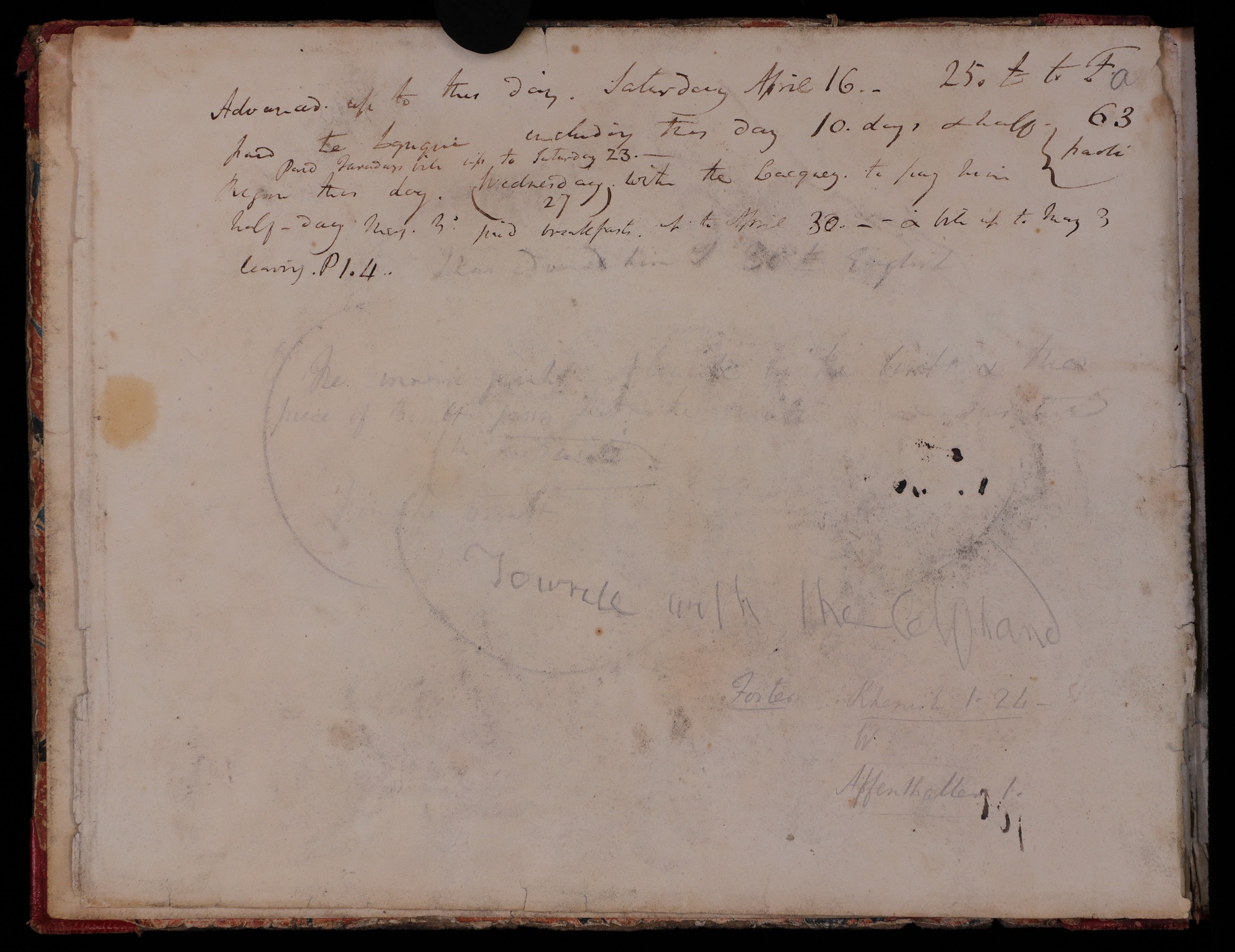

The use of pencil in manuscript notebooks causes no end of problems for the reader:

RI MS HD/14/I, front endpaper a (verso) (click to enlarge)

The front endpaper above bears legible text in ink on the top third of the page. Some faint pencil text follows on directly. The pencil text on the middle third of the page is so faint in parts that it’s barely legible. This is largely caused by the slight rubbing of pages together, while the notebook is closed: while ink makes a stain on the paper, pencil (used with normal pressure) only leaves a surface residue, which wears off over time as the notebook is handled and used. No matter how painstaking the curatorial care a notebook receives, the pencil will wear away and smudge over time: even handling the notebook only occasionally will cause minute rubbing of the pages, which will in turn cause the pencil text to deteriorate.

As a doctoral student, I was fortunate enough to spend several hours consulting Percy Bysshe Shelley’s so-called ‘Drowned Notebook’ (Bodleian MS Shelley adds. e. 20): the water-damaged notebook recovered after Shelley’s death from drowning in the Bay of Spezia in 1822. Photographs were taken of this notebook in the early twentieth century, and also deposited in the Bodleian Library; I had these alongside the manuscript notebook as I worked. Even though the notebook had been afforded the very highest level of curatorial care, the deterioration, in comparing the manuscript with the photographs, was marked – it’s simply time that does this, the fragile notebook representing the antithesis of Shelley’s ‘[t]ablets that never fade’ (Queen Mab, Canto vii, l. 53). Pencil, while having its advantages, such as ease of use outdoors, is notoriously unstable as a writing medium; one of the aims of the Davy Notebooks Project is to ensure that Davy’s valuable manuscripts are digitally preserved for future generations. Who knows what the page above will look like in a hundred years’ time?

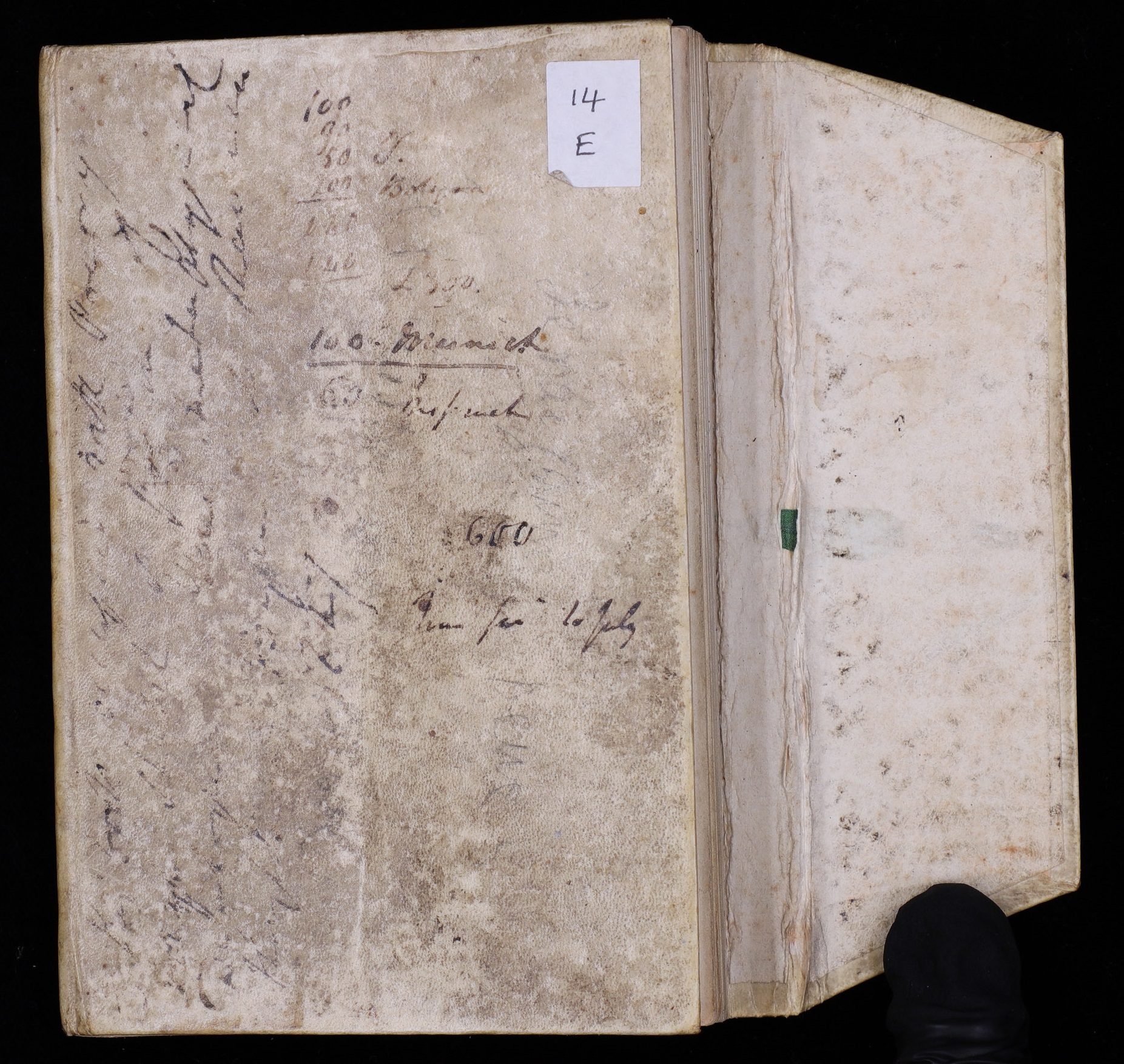

Writing on materials other than paper also causes problems in terms of textual stability. Several of Davy’s notebooks, including RI MS HD/14/E, are bound in leather or calfskin:

RI MS HD/14/E, back cover (click to enlarge)

RI MS HD/14/E, back cover, detail, rotated (click to enlarge)

Notebook 14E, used towards the end of Davy’s life, in 1827, is covered in calfskin. In Davy’s oeuvre, this is fairly unusual: we currently know of only three notebooks with this covering. The text in this notebook is generally very legible; the same, of course, cannot be said for the ink on the covers (both front and back). Whether the ink persisted for a short while and rubbed off, owing to the interaction of this particular specimen of calfskin and the ink that Davy was using at the time, or whether the ink took well to the surface and has simply deteriorated over the years is a matter of conjecture; the end result is the same. We’ve encountered similar instances of difficult-to-decipher ink on leather covers too. Again, this makes the case for the importance of the digital preservation of the notebooks that the Davy Notebooks Project is undertaking.

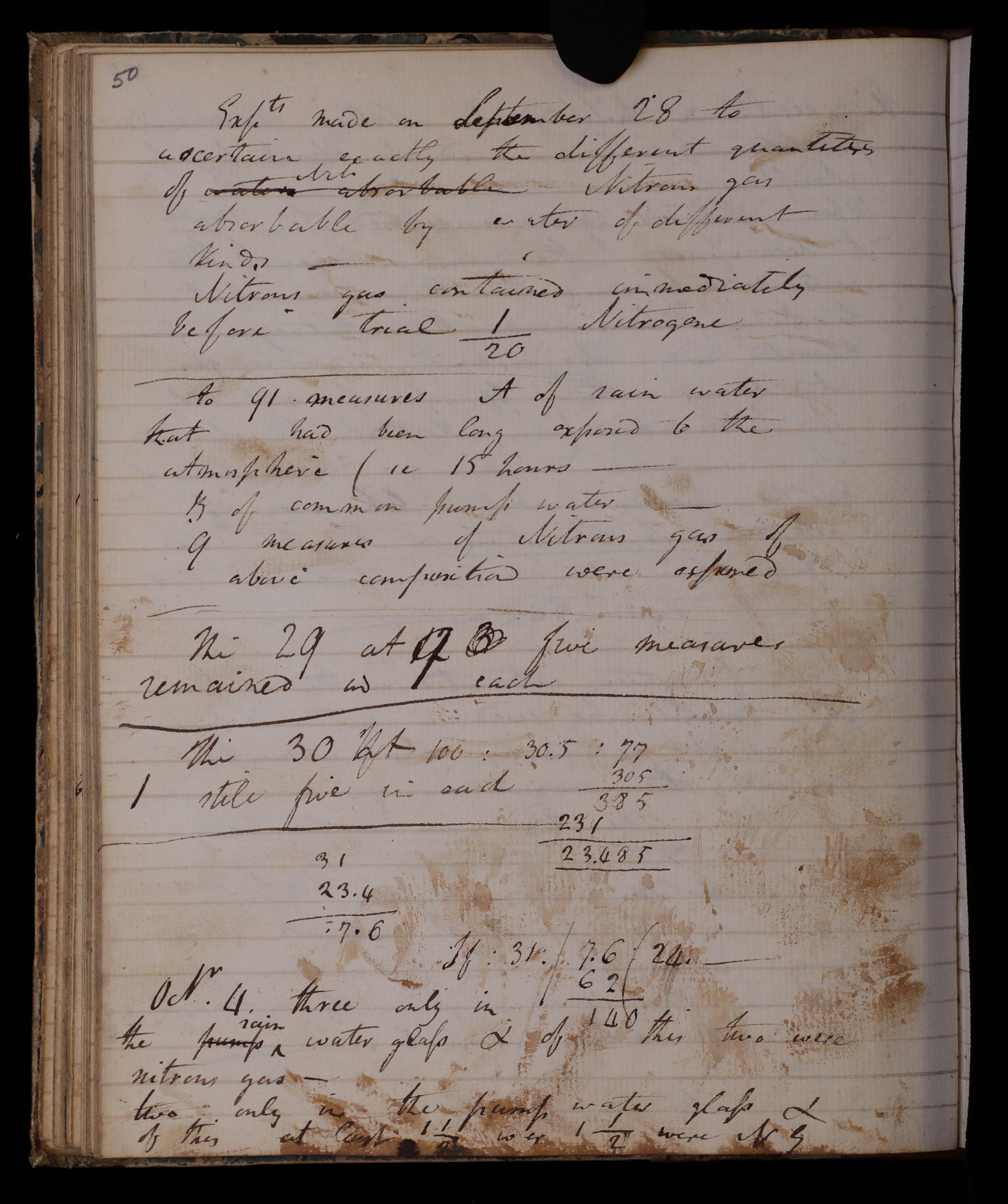

Working with the notebooks of a chemist presents its own set of material challenges. Notebook 20C contains several pages with what appear to be chemical staining, such as this one:

RI MS HD/20/C, p. 50 (click to enlarge)

While, in this case, we’re fortunate in that we can still make out the text affected by the staining (is it a chemical reagent, or the product of a chemical experiment, perhaps?), the two spots of darker staining at the very bottom of the page threaten to obscure the text. In fact, we can only read the denominator in the first fraction with a moderate degree of confidence: it appears to be a ‘2’. If the staining was heavier, the text may well have been completely obscured. As we continue to transcribe Davy’s notebooks, several of which he had alongside him in the laboratory as he worked (as he apparently did notebook 20C), we might encounter more challenging cases than this.

All of the examples considered above serve as a reminder that manuscripts are fragile objects, in a state of slow, yet unremitting, decay. Their fragility is, in my view, one of the things that make manuscripts both beautiful and special as objects: the apprehension that these ‘tablets’, filled with compelling evidence of what Keats called a ‘living hand, […] warm and capable’, do ‘fade’, and are always fading in a variety of ways, reminds us of our obligation as Davy scholars to do our utmost to preserve, in the best ways we presently can, the materials therein for future generations.

—

[1] The Davy notebooks we’ve worked with so far are, on the whole, in generally good or very good physical condition. The examples I discuss below, from the work we’ve done to date, have been selected as being notable exceptions to this general rule.

[2] The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, ed. by Tim Fulford and Sharon Ruston, advisory eds. Jan Golinski, Frank A. J. L. James, and David Knight, assisted by Andrew Lacey, 4 vols (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), i, cxci.

[3] John Davy, Memoirs of the Life of Sir Humphry Davy, 2 vols (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1836), i, 107-9.

[4] In the case of page stubs – pages cut closely to the binding, sometimes entirely blank, and sometimes with only initial letters or initial part-letters visible – some impressive reconstructive work has been done by the editors of the Cornell Wordsworth series. In several instances, the editors were able to establish, with a relatively high degree of confidence, which of Wordsworth’s draft poems stood on the excised pages left as stubs by collating legible and/or probable first letters on the stub with the first letters of lines in a working database of Wordsworth’s draft and published poems.