13-14th July 2017, Science Museum, London.

Programme

Thursday 13th July, Blythe House (Project team and speakers)

| 9.45 | Tanner Room – Registration & coffee |

| 10.15 | Clothworkers Seminar Room

– Introductions and Welcome: Tim Boon (Science Museum) and Sandra Kemp (V&A) |

| 11.00 | – Tim Boon introduces the Science Museum archive / 1876 case study

– Tim Boon leads object study session with objects from the Science Museum |

| 12.30 | Tanner Room – Lunch |

| 1.30 | Sandra Kemp and Chiara Zuanni (V&A) lead object study session with V&A Indian Writing box |

| 2.15 | Christopher Marsden (V&A) – Introduction to the V&A archive: science and art |

| 3.15 | Tanner Room -Tea |

| 3.30 | Clothworkers Seminar Room – First roundtable – chaired by Sandra Kemp |

| 5.00 | Tim Boon – wrap up |

| 5.30 | Ends |

Friday 14th July, Dana Centre (open to externals)

| 9.00 | Registration & coffee |

| 9.20 | Introductions and welcome – Tim Boon and Sandra Kemp |

| 9.30 | Sandra Kemp – Themes arising from Day One and the press and public reception of the 1876 and Trocadéro exhibitions |

| 10.00 | Second roundtable – chaired by Andrè Delpuech (Musée de l’Homme) |

| 11.15 | Coffee |

| 11.30 | – Séverine Dessajan (Université Paris Descartes – CNRS) – Scientific and artistic contributions to the foundation of the musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro |

| 12.30 | Lunch |

| 1.30 | Session led by Chiara Zuanni and Rupert Cole in the Science Museum’s ‘Making of the Modern World’ Collections |

| 2.15 | Third roundtable – chaired by Tim Boon |

| 3.15 | Tea |

| 3.30 | Closing Discussion – chaired by Hervé Ingelbert (Université Paris Nanterre)

– Hervé Ingelbert – Rapporteur, drawing together threads from the two days – Discussion |

| 5.00 | Ends |

Abstracts and biographies

Sandra Kemp

Introduction to the ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ project and the workshop themes

The ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ (UHUM) project aims to investigate theoretical and historiographical concepts of ‘universal histories’ by comparison with the shaping of historical narratives, taxonomies and epistemologies in museum collections, between 1851 and 1914. Our methodology is underpinned by transnational comparison of the history of the development of museum collection and display practices, and their reception. This workshop brings together a range of presentations relating to two of our project case studies: the 1876 Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus at the South Kensington Museum (predecessor of the V&A and the Science Museum) and the early history of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro, including the international ‘Retrospective’ exhibition in 1878.

Prof Sandra Kemp, is a Senior Research Fellow at the V&A and ICL, and Principal Investigator on the ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ project.

Detail from the Memorial to Sir Henry Cole, designed by F. W. Moody on the V&A West (Ceramic) Staircase, 1878, to commemorate Cole’s contribution to the founding and development of the South Kensington Museum, showing the science and art logos and a vision of ‘Albertopolis’ with institutions which combined both.

Tim Boon

Tim Boon is Head of Research and Public History at the Science Museum. He is on the project advisory board for the UHUM project and co-organised the workshop, which will draw upon a body of work from a previous Science Museum research project on the 1876 Exhibition (which can be found here).

Christopher Marsden

Introduction to the V&A archive: science and art

This presentation will introduce the V&A Archive and show materials which document the workings of the Department of Science and Art, and the evolution of the South Kensington Museum.

Paintings on the staircase of the Science Schools (aka Henry Cole Wing).

Rupert Cole

Static displays: exhibiting the Royal Institution’s Nairne machines, 1802 – present

Founded in 1799 and housed in its original building, the Royal Institution (RI) is a scientific and cultural institution that has been primarily concerned with both research and the communication of science to the public. Through its 218-year history it has witnessed not only the development of its own institutional heritage but also that of scientific heritage more generally.

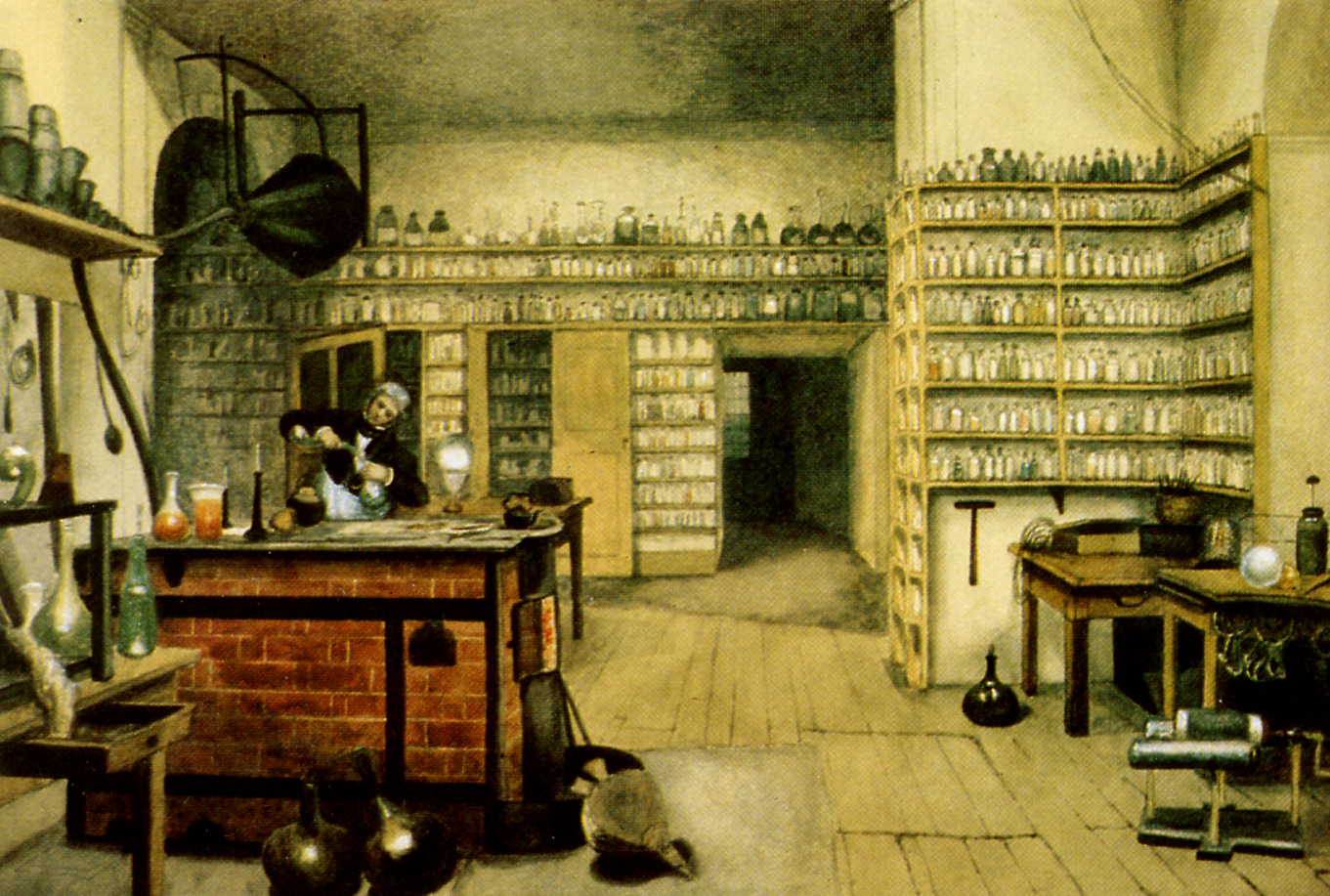

This paper charts the displays of two of the RI’s Nairne machines, devices invented by the instrument maker Edward Nairne in the late 18th century that were used to generate static electricity by frictional means. I will examine a series of images of when these machines have been displayed, including: a famous Gilray caricature of an 1802 Humphrey Davy lecture at the RI; Harriet Moore’s 1850s watercolour paintings of Michael Faraday’s laboratory; and a number of photographs of the RI’s museum as it evolved during the twentieth century. By doing so, the paper will reflect on how these different media have captured temporary moments of display, providing a permanent record of the process by which some of the RI’s scientific instruments have come to constitute a collection of historic objects. By reconstructing the cultural contexts in which these Nairne machines were displayed, I will ask broader questions about the emergence of heritage and the creation of a museum collection.

Rupert Cole is an Assistant Curator of the Science Collections at the Science Museum, London.

Michael Faraday in his laboratory, by Harriet Moore.

Jonathan King

Gallery or Greenhouse? Francis Fowke and the origin of ethnographic museum design.

Walter Benjamin famously chose to study Arcades as a building type. Glass-covered, with cubicles for shops, arcades as a source of inspiration for 19th century exhibition and museum buildings have been overlooked. Museum design initially developed in the 18th century from the idea of a series of interconnecting palace apartments or galleries as at the Louvre or for the original 17th century French-style British Museum building, Montagu House. A new tradition arose from the 1830s, with the development of the arcade-style top lit Hunterian Museum and Museum of Practical Geology of the 1830s. With the Great Exhibition of 1851, horticulturalist Joseph Paxton hugely expanded the emphasis of the top-glazed building as a gallery prototype. Paxton’s work was continued in the 1860s by Francis Fowke, another autodidact. In the 1860s Fowke was sent to Edinburgh by Playfair and Cole of the South Kensington Museum, to create the Industrial Museum, and he also designed the 1862 (London) International Exhibition building. It was these two galleried buildings, with huge atriums ringed with balcony displays, whose designs gave rise to England’s best known university ethnographic museums: the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, and the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge. Dostoyevsky famously noted of Fowke’s 1862 exhibition that “a feeling of fear somehow creeps over you… It is a Biblical sight, something to do with Babylon, some prophecy out of the Apocalypse being fulfilled before your very eyes”, a description which might apply to early ethnographic museums as the representation of world chaos, as much as that of world cultures. Alternatively the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (1882) referred partially to the initial tradition, with interconnecting palace-style apartments. This paper will contrast the emergent museum architecture of the 1880s.

Dr Jonathan King. Senior Fellow, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Von Hugel Fellow, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge.

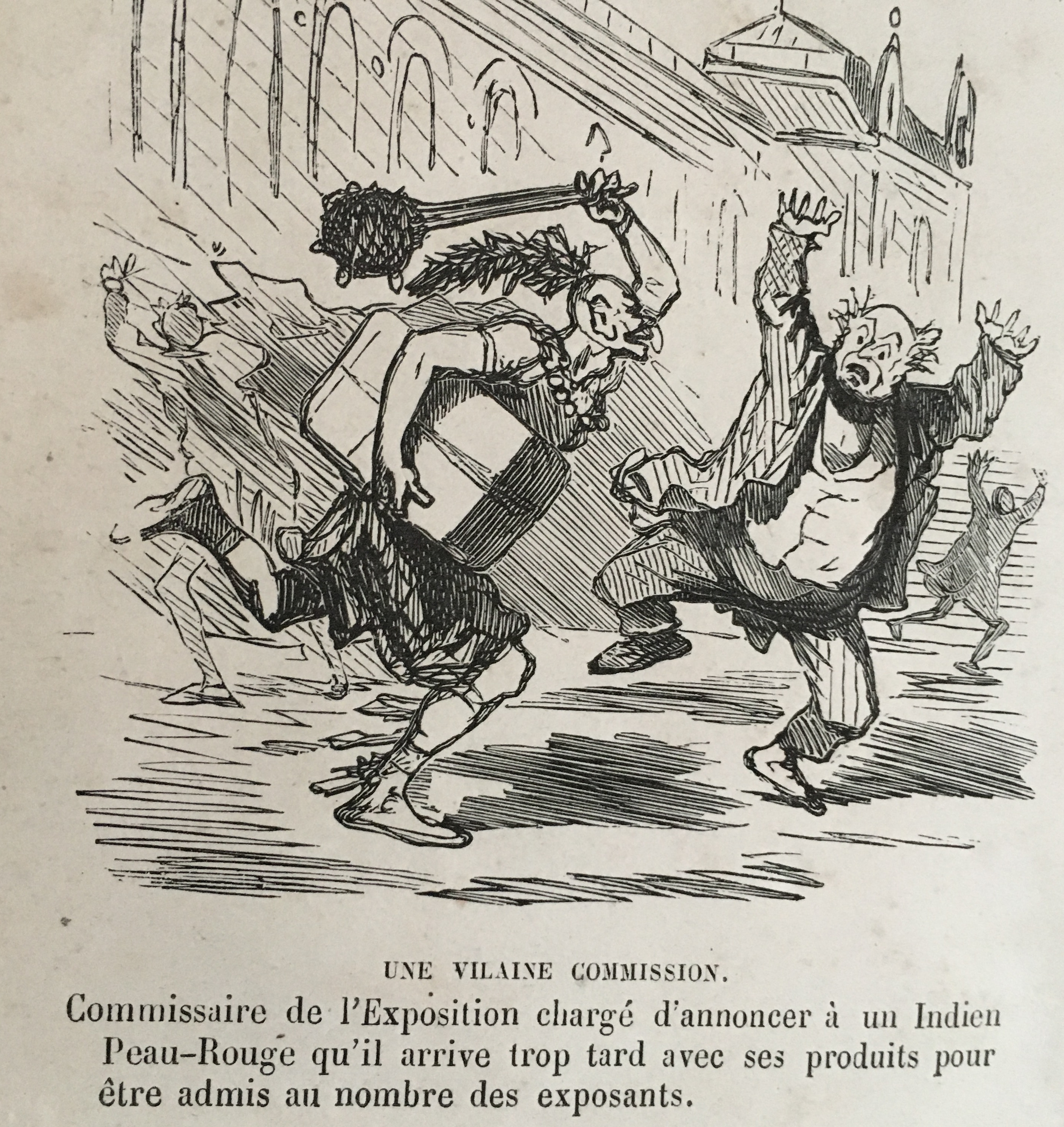

A French view (by Cham) of a Native American contributor to the 1862 London exhibition – in front of Fowke’s building.

Alexander Scott

Universal Exhibitions, Municipal Ambitions: The 1851 Great Exhibition and the Origins of Liverpool Public Museum

This paper presents a localised case study of the impact of universal exhibitions on the creation and development of museum collections. Whereas the impetus that the Great Exhibition of 1851 provided for the creation of South Kensington’s museums is well-known, the paper identifies a less-documented parallel in the exhibition’s relationship to museum collections in Liverpool. As my analysis demonstrates, the exhibition intersected with, and influenced, the early history of the Liverpool public museum in numerous ways. For one thing, Liverpool’s museum was first instituted by its town council whilst the exhibition was actually taking place in Hyde Park, and, accordingly, supporters of the museum expressed hopes it might become a Liverpudlian equivalent to London’s Crystal Palace. Such grand ambitions gained credibility from displays at the Great Exhibition. Like other municipalities, Liverpool used the exhibition as a platform to promote its local industries, arranging for samples of thousands of imports plus a miniature model of its docklands to be put on show inside the Crystal Palace. These exhibits attracted admiring reviews from exhibition judges – so much so that a delegation of officials from London made a special visit to inspect Liverpool’s maritime activity first-hand. This endorsement lent extra momentum to plans for the Liverpool museum, with exhibits that had been on display at the Crystal Palace amongst the principal attractions when the museum opened its doors to the public in October 1852. In subsequent decades, Liverpool museum built on this initial success, accruing an international reputation for housing natural history, archaeology and anthropology specimens from around the world. In this sense, the paper concludes, the museum managed to fulfill the rationale behind Liverpool’s contributions to the Crystal Palace, plus the motivations underpinning the Great Exhibition as a whole: a desire for ‘object lessons’ of the perceived virtues of free trade and imperialism.

Dr Alexander Scott, University of Wales Trinity St David. My research and teaching interests span various aspects of cultural history, with a particular emphasis on cities. I have been a Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Wales Trinity St David since 2015. Prior to this, I completed a PhD at Lancaster University with a thesis on the history and contemporary status of museums in Liverpool.

Dickinson Brothers, Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851 from the Originals Painted for HRH Prince Albert ( London: Dickinson Brothers, 1852).

Sandra Kemp

Themes arising from Day One and the press and public reception of the 1876 and Trocadéro exhibitions

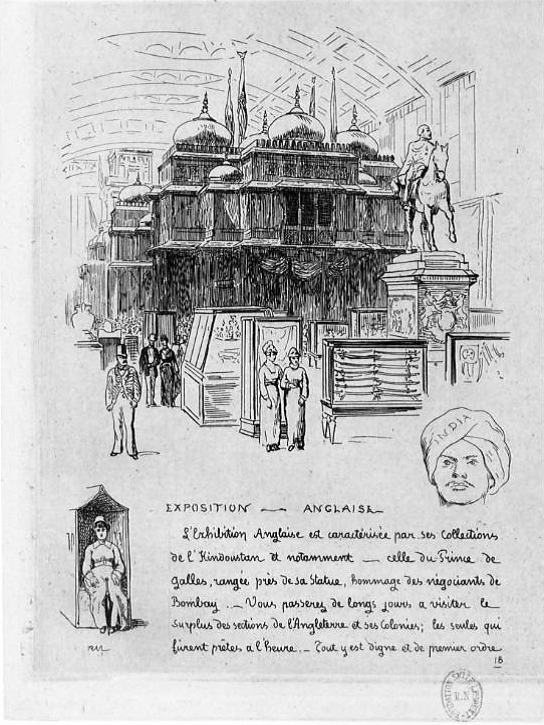

On 13th February 1875, the Lords of the Committee of Council of Education in the British Parliament proposed the future ‘enlargement’ of the South Kensington Museum “into a Museum somewhat of the nature of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers in Paris; and other similar institutions on the continent” (Catalogue of the Special Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus, p.xi). Three years later, reviewing the ‘Retrospective’ exhibition at the Trocadéro, an English curator made an unfavourable comparison of the British collections, pedagogy and display practices with the “method, lucidity and instructiveness which seem natural in the French”. This presentation will make transnational comparisons between the development of the South Kensington and Trocadéro museums through the eyes of a number of key protagonists in London and Paris: museum administrators and curators, the press and the public. Referencing internal committee papers, and publications produced to support visitors such as Handbooks, Catalogues and Conferences as well as press and journal reviews, it will investigate the temporary exhibitions as a “zone of cultural debate […] where types, forms and domains of culture are encountering, interrogating and contesting each other in new and unexpected ways” (Appadurai and Breckenridge, 1988: 6).

L’Exposition Universelle 1878. Lettre illustrée. Paris-Gravé 1878, p.21. The Indian Palace in the Champs de Mars during the 1878 International Exhibition.

André Delpuech

André Delpuech is Director of the Musée de l’Homme. Previously he was Head of Collections and Americas at the Musée du quai Branly.

The Palais du Trocadéro in Paris, 1890s (source: US Library of Congress ).

Pascal Riviale

Peruvian collections at the origins of the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro. From the 1878 Universal Exhibition to the opening of the museum in 1882

At the beginning of 1877, the arrival of some antiquities in France, brought by Charles Wiener returning from his mission in Peru and Bolivia (and displayed at the 1878 Universal Exhibition in Paris), constituted a major contribution to the decision of founding a new ethnographic museum in the capital city. The almost simultaneous acquisition of other collections (Pinart, Cessac, Ber, Vidal-Senèze, Drouillon) would strengthen the prominent position of Pre-Colombian Peru in the collections of the museum at its inauguration at the Palais du Trocadéro in 1882. The analysis of these acquisitions reveals the diversity of the journeys of these collections, and the circulation of objects before and after entering the museum.

Dr Pascal Riviale. Archives nationales, research fellow at the EREA centre at LESC (CNRS-Université Paris Nanterre) and at the Institut français d’études andines (UMIFRE 17).

Back to the top

Séverine Dessajan

Scientific and artistic contributions to the foundation of the musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro

The slow creation of the ‘Musée d’ethnographie des missions scientifiques’ in the 1870s needs to be considered in the diverse stages of its foundation. This museum found a site in the old Palais du Trocadéro for the occasion of the 1878 Universal Exhibition and its doors opened to the public the following year. The government allocated the museum its first budget in 1880, and this gave rise to the first ethnographic galleries for a wider audience from 1882. Many disciplinary reflections affected every stage of the museum’s history until 1938, the year in which the Musée de l’Homme opened within the same site. Thus the boundaries of ethnography, ethnology and of anthropology began to emerge in parallel with the acquisition of objects from the colonies, among others, and their new display in this museum. The initial project of the Musée d’ethnographie du Trocadéro was to present a “cultural history of people” differing from the Jardin des Plantes, which was responsible for the “natural history of humankind”. This process led to the constitution of its collections, originating from missions around the world financed by contemporary French governments, showcasing the colonial expansion. This type of displays corresponded with a change of perspective on the so-called distant arts, ranging from repulsion to fascination until proposing a form of encounter with otherness. This paper will present a reflection on the development of a museum project, closely linked to the foundations of the humanities in a dialogue with the constant renewed interest for the redevelopment of non-Western arts.

Dr Séverine Dessajan has a PhD in social anthropology and ethnology (EHESS, 2000) and is an engineer at CERLIS (Centre de recherche sur les Liens Sociaux) at Paris Descartes University.

Back to the top

Magdalena Ruiz Marmolejo

The first ethnographical collections in Paris: Amazonia in the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro.

For what reasons did collectors such as Paul Broca acquire around 20 Munduruku objects? What has happened afterwards to these objects? Who are the explorers who went on a mission mainly to the French and Brazilian Amazonia to collect weapons, ornaments and other Amerindian objects? What representation of ‘the Other’ do we have considering the contribution of material culture in the collections of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro? Through the examination of some emblematic case studies, I will focus on the reciprocal relations established between the Musée d’Ethnographie, private collectors and explorers such as Jules Crevaux, Henri Coudreau and Jean Chaffanjon, sponsored by the French Department of Education.

Then, for comparison, I will also consider Karl von den Steinen, pupil of Adolphe Bastian, the father of German ethnology who discovered the Xingu (in Brazil) and gathered an impressive collection. Following its second expedition, the Museum of Ethnology in Berlin acquired a major role among ethnological museums, and thus coordinated and supported the collections of other museums in Germany, such as those of Hamburg, Leipzig and Munich, offering them important Amazonian ethnological material.

Magdalena Ruiz Marmolejo is a Heritage Curator, specializing in the arts of the Americas. She is also pursuing a doctorate on Amazonian ethnological collections in European museums, at the University of Paris-1 Sorbonne and the Ecole du Louvre, under the supervision of Stéphen Rostain (CNRS) and André Delpuech (Director of the Musée de l’Homme).

Back to the top

Déborah Dubald

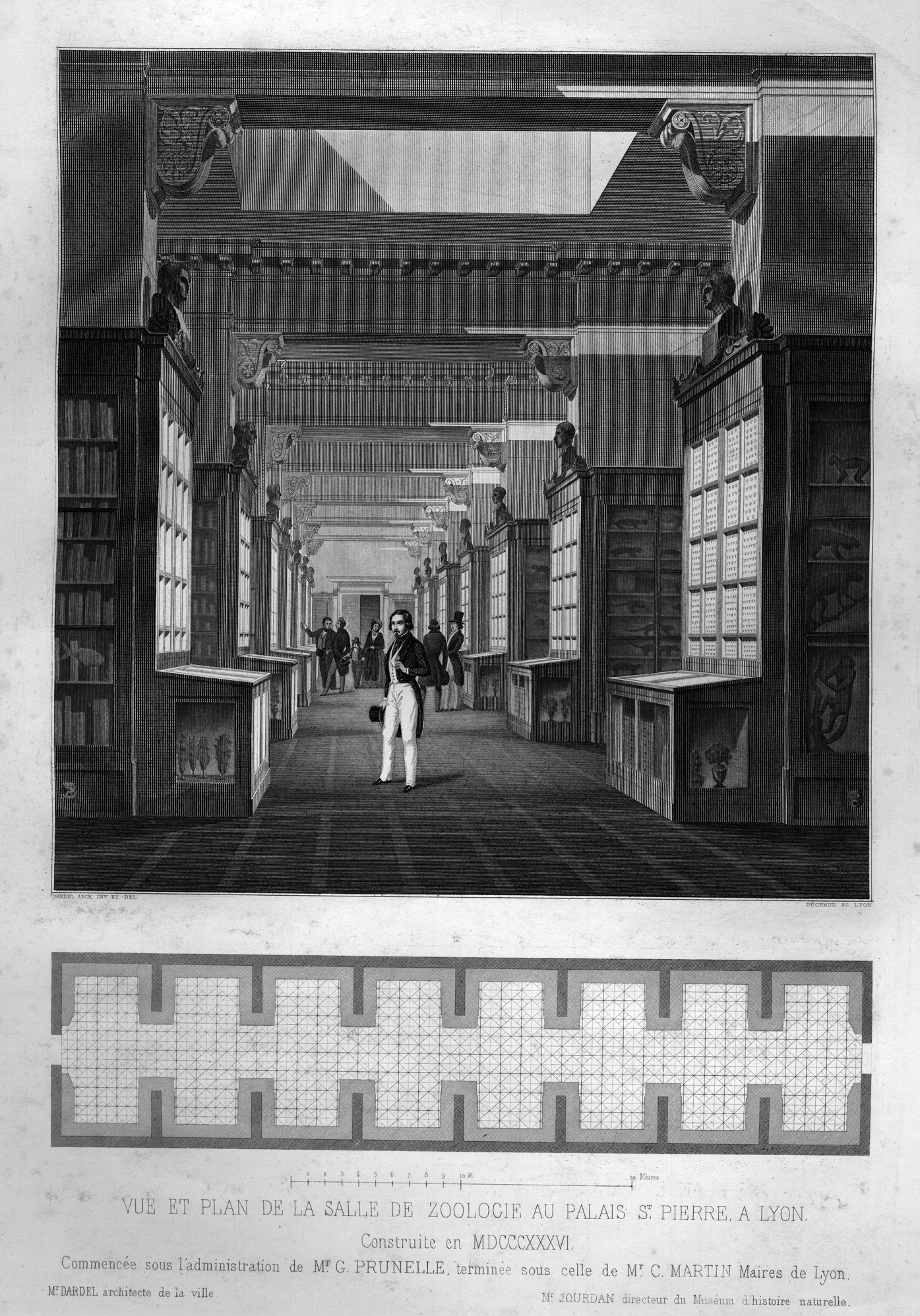

‘La nature dans son ensemble se déroulera sous vos yeux’: manifold protagonists, changing spaces and natural knowledge in Lyon, 1800-1870

The Zoology Gallery of the Lyon Natural History Museum was inaugurated in 1837 with an opening speech by none other than the first Deputée-Maire. This event marked an important turn for the then thirty-year-old institution which thereby became a valuable municipal one. The museum emerged during negotiation processes by numerous, successive protagonists: the museum and botanical garden staff, members of the local learned societies, faculty of science professors and the political – especially municipal – authorities. The museum display in the exhibition consisted of the entire collection of the museum, in an attempt to deliver an exhaustive and possibly universal image of nature. In a context of ‘museological science’ (Pickstone, 2009), museums built their scientific authority around collections, that is the primary material and instrument of which science was made. In this case, both the users and visitors of the museum were essential (albeit not exclusive) protagonists who contributed to the making of the museum. They worked together to build a new collection of zoology, and contributed to the discussion of whether the natural history collection should be kept at the botanical garden, at the museum itself or merged with the Académie’s collections. Whether the uses of the museum were political, educational or even to support ongoing research, this multifaceted group of people were constantly interacting. In this paper, I will expose how several types of actors influenced the disciplinary and, especially, the spatial organisation of natural history both within the museum building itself and within the city of Lyon. This case study will investigate the nature of relations between museum protagonists and how they affected the structure of the museum and its progressive consolidation as a central and authoritative place for science.

Déborah Dubald is a third-year PhD researcher at the European University Institute, Florence, whose research focuses on natural history museums and the French city in the first half of the nineteenth century. She is the co-founder and co-ordinator of the History of Science working group at the EUI. Prior to this, she studied History at the University of Strasbourg (2000-2006).

View and plan of the Geology Gallery at the Palais St. Pierre, Lyon.

Roberto Limentani

The primitive form of things. Museography and science in Pitt Rivers’ anthropology of material culture.

In 1876, Pitt Rivers, director of the Anthropological Institute, participated in the scientific committee in charge of the Loan Collection of Scientific Apparatus. In 1874, he had organised a first exhibition at the Bethnal Green Museum, an expansion of the South Kensington Museum that had been founded with the aim to provide an educational institution to the working class suburbs of London. In 1884, he donated part of his collection to the University of Oxford, which named the ethnographic museum after him. However, Pitt Rivers was only indirectly involved in arranging the objects of his collection. In the same year, he opened a private museum in Farnham where he organised his collections according to his idea of typology.

With this paper, I will address the implications of his typological approach. I will examine how and why his scientific program has not yet been fully described. To do so, I will draw from Darwin’s distinction between natural selection and variation under domestication, and the theory of the origins of language proposed in 1861 in England by German linguist Max Müller. By clearly distinguishing the role taken by comparison from the analysis of forms in his programme, I will evaluate its actuality. Furthermore, by analysing his writings by the yardstick of the visual supports that he used during his demonstrations, I will discuss the relation between his museography, his position on the education of working classes, and Galton’s phylogenesis. I will ultimately outline one general feature of anthropological theories unusually evident in his thought. Anthropological theories resemble the artefacts studied by Pitt Rivers; they determine an image of the subject by allocating him a place.

Dr Roberto Limentani. EHESS/LAS (Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales, Laboratoire d’Anthropologie Sociale).

Sue Johnson, Domesticated Gourd Plant, 2010. Gouache, watercolour and color pencil on paper, 30 x 22 inches, Pitt Rivers Museum Collection, University of Oxford.

Hervé Inglebert

Hervé Inglebert is a Professor of Roman History and Head of the History department at Université Paris Nanterre. He is the French Principal Investigator on the UHUM research. He will draw the themes discussed during the workshop, in light of his expertise on universal histories.

Chiara Zuanni

Preview of the project online exhibition with ‘spotlight’ objects for from the 1876 and Trocadéro exhibitions

This presentation will outline work-in-progress on the structure and thematics of the online exhibition that is being developed as part of the ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ project. Centred on object biographies relating to the development of collections in Paris and of the South Kensington Museum in London during the second part of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, this exhibition comprises a core part of our research process as well as a means of dissemination. We would like to use our exhibition preview to bring together some of the core themes of the workshop, and to invite workshop participants to contribute to the development of the exhibition content and template.

Dr Chiara Zuanni is a Research Fellow at the V&A and the postdoctoral assistant on the ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ project.