DESIGN THINKING MATTERS NOW

The theme of this d.confestival is a provocation to reflect on the impact and relevance of design thinking to the priority challenges of our time. We play on ‘matter’ as both verb and noun: Why, when, how and for whom does Design Thinking matter? What are the matters on the agenda for the field of Design Thinking in 2022?

We are bringing insights from our Good Place Innovators project to the forum with our interactive sessions Transforming Communities through Design Thinking: Sharing practice from developing an immersive, multi-stakeholder university module interconnecting enterprise and design.

Our session is laid out on this page below for easy navigation.

Recording of the session is available here .

1. Design matters to Us

As regenerative education designers, we commit to uphold our pledge:

– We will support students as responsible change agents and co-designers of their learning experience

– We will advocate the changing role of the educator, moving from classroom authority to facilitator with design mindset

– We will collaborate with society stakeholders to co-create our curriculum centered around relevant place-based challenges

Podcasts

Designing with, designing for and designing by

Place is owned by everybody

2. IMAGINE THAT

Are you ready for a little challenge? We think you are. Just sit back, let your brain wonder and enjoy! We cannot wait to hear what you imagined…

Imagine!

In this activity, you are given a seemingly unreal scenario in a form of a question. Get creative about how you answer it!

forkText

We also imagined…

If Design Thinking moved beyond case studies, workshops and hackathons, would we improve our capabilities to navigate and transform the ever-challenging world?

- Design Thinking (DT) has gained recognition as a transformative, cross-disciplinary philosophy, practice and skill-set in management and business education.

- There is a significant gap in understanding how to teach DT in a way that conveys its true transformational ethos.

- Design Thinking “cannot be taught through traditional lecturing pedagogy” (Çeviker-Çınar et al, 2017, p. 985) and that business people “don’t just need to understand designers, they need to become designers” (Martin, 2017)

- Design Thinking suffers a reduction to a model simplifying the complexity of real-world challenges.

- This gap in creating and implementing adequate pedagogical methods is the focus of our three-dimensional conceptual model.

Closing The Gap

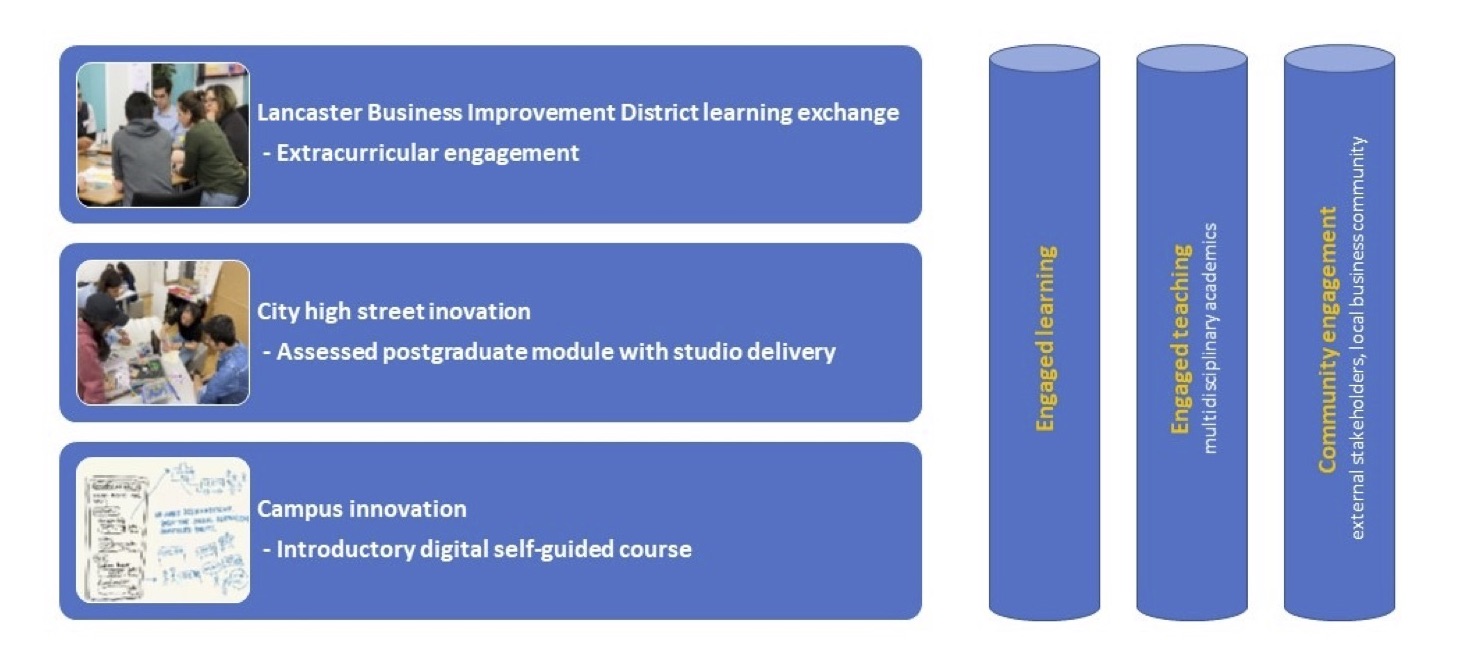

Figure 1: Three-dimensional approach to curriculum design with three engagement pillars (Newton and Rindt, 2022)

3. What inspired us?

- What is one thing you observe – don’ t try to make sense of it, just observe and describe what you see.

- Why might this be happening? – add your interpretation, empathise with these students you see and focus on possible challenges and frustrations of these students you see on the photos.

- This inspires me to think about solutions that… – can you think of any products or services that the students would really appreciate on the Campus?

Design for Good Place

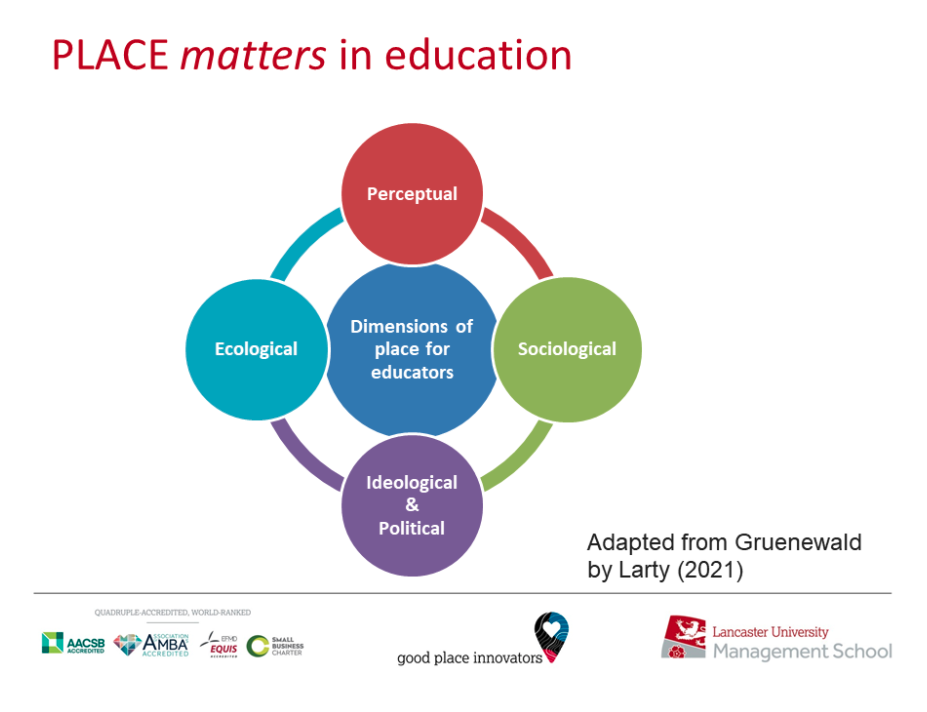

The foundation paper related to place-based curriculum has been published by our colleague Joanne Larty (2021) who also speaks about this approach in our podcast Are we becoming more transient and less conscious of our place?

- Perceptual dimension: encouraging students to engage with people and places as part of their learning.

- Sociological dimension: recognising how local cultures and customs both enable and constrain opportunities for innovation

- Ideological and political dimension: understanding how structures of power might enable or constrain intentions to be innovative.

- Ecological dimension: understanding the impact of innovation on local natural environments.

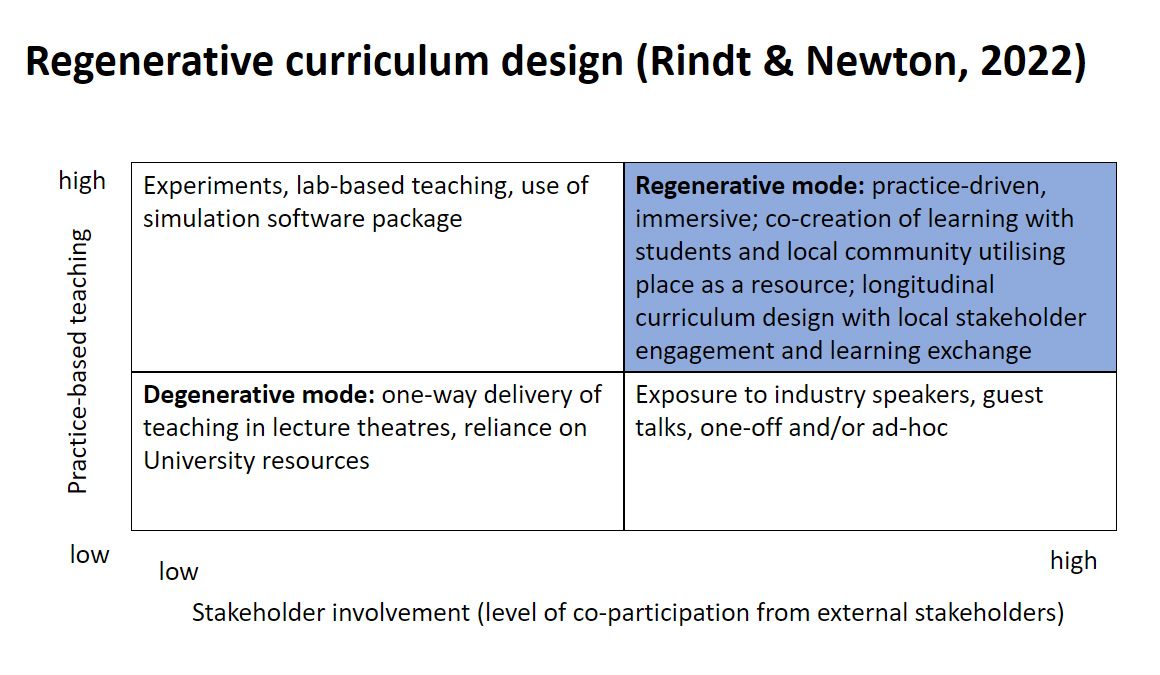

4. Paradigm Shift in HE: From degenerative to regenerative curriculum design

Figure 2: Regenerative curriculum design (Newton & Rindt, 2022)

- ‘Regenerative Curriculum Design’ model: a systematic approach to curriculum design, that is characterised by practice-based, immersive, stakeholder and context-driven teaching and learning (Bason & Austin, 2019)

- Anderson’s vision: to tangibly advance the development and well-being of the local community (Loi & Fayolle, 2022).

- It revolves around a real-life challenge, rather than a simulated case, and is formed on the pillars of community engagement, engaged learning and teaching.

- Students become ‘agents of change’ and lecturers facilitate a longitudinal, real-life experiment where students and local communities engage in co-designing solutions for pressing local challenges.

- Stakeholders and students are co-creators of the curriculum, which evolves and grows through this continuous interaction, not a mere ‘handing over’ of resources to the students.

- The second meaning of the ‘regenerative’ curriculum design relates to the regeneration of the local place and community that the students and universities are embedded in.

5. Student-led placemaking

“We are all super excited to witness the changes our ideas can initiate and are proud of ourselves to help make contributions to the city we now call home.”

Co-designing a better Lancaster city experience with Lancaster Business Improvement District (BID)

– tackling socio-economic challenges of our city in a way that is human-centred, experimental, iterative, creative and collaborative

– exploring Design Thinking practices with external stakeholders in pursue of common purpose

– recognising students as citizens with designer mindset and commitment to a better future

Podcast

6. Good Place Lab

Good Place Lab is a self-guided digital experience celebrating the creativity and fun aspect of Design Thinking, exploring the importance of people we design with and place we design within and developing design capability to deliver value and drive impact in our world!

- It is fun

- It is adaptable

- It is there for you to enjoy it!

If you are interested in adapting the Good Place Lab for your students, or giving us feedback and suggestions for improvements, drop us a line or comment on the Innovation board.

If you want to have a go, simply DO IT! We can’t wait to see your innovations of our beautiful green Lancaster Campus.

Thank you

7. References

Anderson, N., Adam, R., Taylor, P., Madden, D., Melles, G., Kuek, C., Wright, N. and Ewens, B., 2014. Design thinking frameworks as transformative cross-disciplinary pedagogy, Report published by the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Education, Sydney, N.S.W. pp. 1-55.

Bason, C. and Austin, R.D., 2019. The right way to lead design thinking. Harvard Business Review, 97(2), pp.82-91.

Beligatamulla, G., Rieger, J., Franz, J. and Strickfaden, M., 2019. Making pedagogic sense of design thinking in the higher education context. Open Education Studies, 1(1), pp.91-105.

Brown, T. and Martin, R., 2015. Design for action. Harvard Business Review, 93(9), pp.57-64.

Buchanan, R., 1992. Wicked problems in design thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), pp.5-21.

Çeviker-Çınar, G., Mura, G. and Demirbağ-Kaplan, M., 2017. Design thinking: A new road map in business education. The Design Journal, 20, pp.977-S987.

Dodd, S., Lage-Arias, S., Berglund, K., Jack, S., Hytti, U. and Verduijn, K., 2022. Transforming enterprise education: sustainable pedagogies of hope and social justice. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, pp.1-15.

Dunne, D. and Martin, R., 2006. Design thinking and how it will change management education: An interview and discussion. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(4), pp.512-523.

Glen, R., Suciu, C. and Baughn, C., 2014. The need for design thinking in business schools. Academy of management learning & education, 13(4), pp.653-667.

Huq, A. and Gilbert, D., 2017. All the world’s stage: transforming entrepreneurship education through design thinking. Education+ Training.

Liedtka, J., 2018. Why design thinking works. Harvard Business Review, 96(5), pp.72-79.

Loi, M. and Fayolle, A., 2022. Rethinking and reconceptualising entrepreneurship education a legacy from Alistair Anderson. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, pp.1-21.

Martin, R. and Martin, R.L., 2009. The design of business: Why design thinking is the next competitive advantage. Harvard Business Press.

von Thienen, J., Ney, S., & Meinel, C. (2019). Estimator Socialization in Design Thinking: The Dynamic Process of Learning How to Judge Creative Work. In R. A. Beghetto & G. E. Corazza (Eds.), Dynamic Perspectives on Creativity, Creativity Theory and Action in Education 4 (pp. 67–99). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland

Wrigley, C. and Straker, K., 2017. Design thinking pedagogy: The educational design ladder. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(4), pp.374-385.

Woudhuysen, J., 2011. The craze for design thinking: Roots, a critique, and toward an alternative. Design Principles & Practices. An International Journal, Vol 5, pp. 1-25.