From June to August 2021, Alexander Theo Giesen joined the Davy Notebooks Project team as a UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies (STS) Summer Studentship holder, and edited the transcriptions of three additional notebooks (14E, 14I, and 20C) that volunteers transcribed during the pilot project. During the pilot, eight of Davy’s notebooks were transcribed by more than 500 contributors across the world, using Zooniverse. Alexander is an MSc student in History and Philosophy of Science at UCL.

Editing the transcriptions of the notebooks from the pilot project involved working with up to five versions of the same page transcribed by multiple volunteers. In its current version, three volunteers transcribe each line in Zooniverse and this is collated into an aggregated transcription in ALICE for collaborative review (you can read more about this here in Alexis Wolf’s recent post). However, for the pilot, amalgamating the transcriptions was a manual process. For each page of the notebook the process was to select one of the transcribed pages and then edit this page, using the others to fill the gaps.

The first day of editing was by far the most difficult. 14E, dating from 1827, is a fascinating notebook crammed from the outset with Davy’s weather reports, health updates, long lists of temperatures at various parts of the room and at different times of the day, and lots of fishing! It contains records of daily fishing trips, detailing the number and size of fish caught, the phenotypical features of the fish, and even the disappointment of not having seen any new fish at the fish market. It was a challenge at first to decipher the names of less familiar European cities and towns, and Davy’s reports of his experiences could at times feel a little uneventful. It took three hours to edit the first three pages of 14E!

Choosing which one transcription to use as a basis for editing each page was something that shifted over time. Initially, it seemed logical to pick the one with the fewest unclear words marked up by volunteers (which they mark up as ‘[unclear]xxxxx[/unclear]’). At the start, picking a page with the fewest unclear words, it took a long time to rearrange the lines to follow the ordering in the notebook. Over time it became apparent that picking a page with the correct ordering of the lines was the quickest way to edit each page. The best way to identify this was to pick the transcription that had the same first and last line as the notebooks. The first thing to do when selecting a new page to edit was to check if the first and last lines are the same as in the original, and the editing process became much quicker after this!

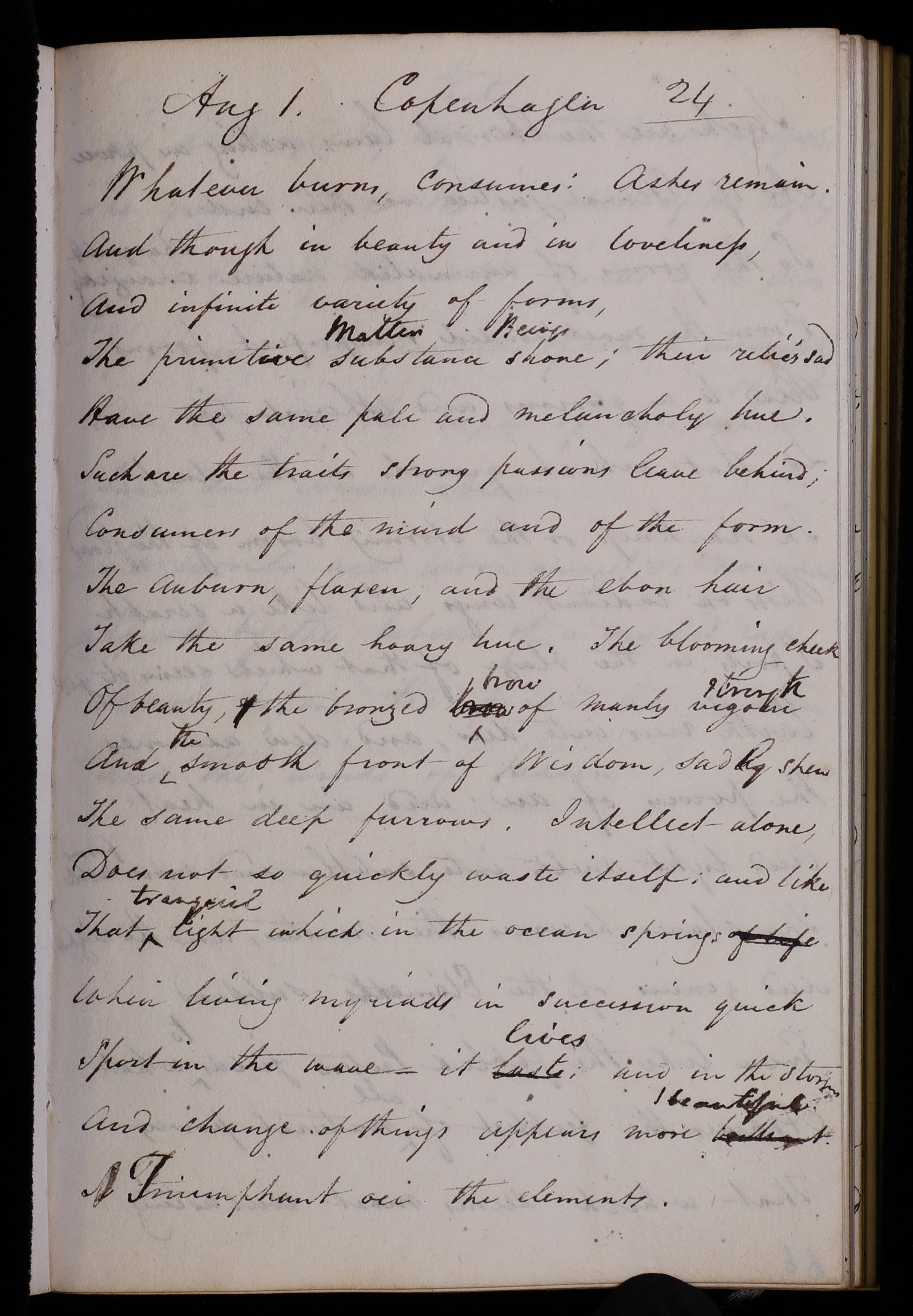

RI MS HD/14/E, p. 100, ‘Aug 1. Copenhagen 24’ (click to enlarge)

Editing the transcriptions of Davy’s poetry was a wonderful experience and it felt easier than editing Davy’s prose. Most of the latter half of 14E and 14I contained some stunning poems. For Davy, poetry appears to be a mode of synthesis. Here, we can understand how his actions relate to himself, his mind, and the universe. Also, there were imaginings that move beyond the scientific to formulate cosmological questions:

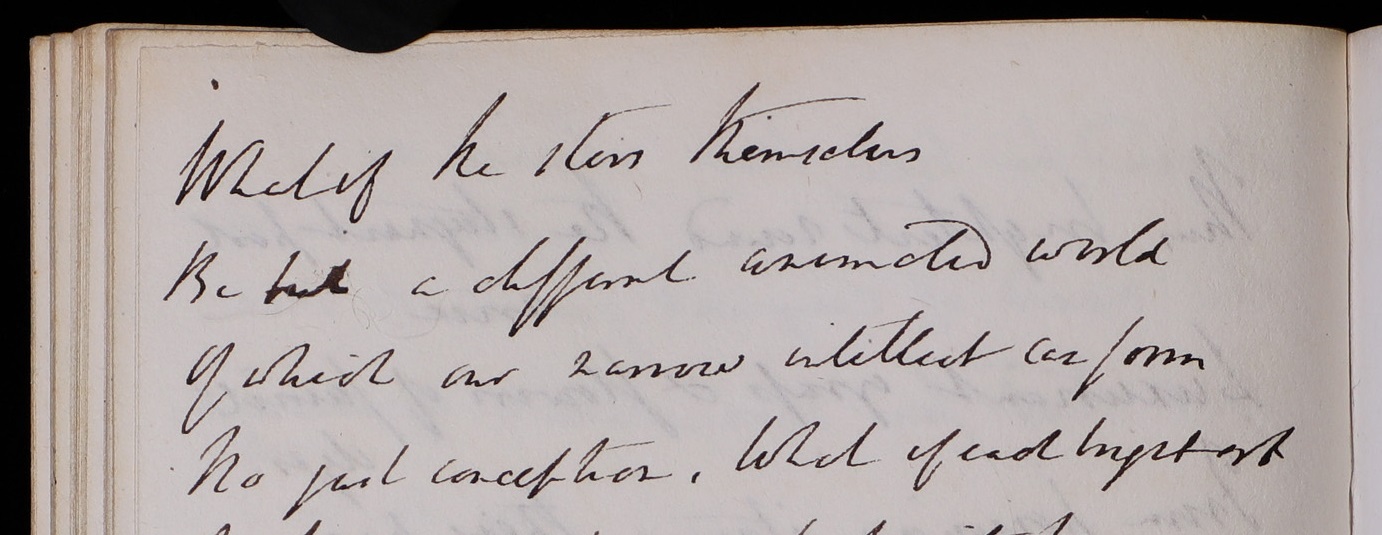

What if the stars themselves

Be but a different animated world

Of which our narrow intellect can form

No just conception. […]

RI MS HD/14/E, from p. 091 (click to enlarge)

Out of the three notebooks, 20C, an early notebook dating from 1800 and Davy’s time in Clifton in Bristol, contained the most reports by Davy of his scientific experiments and theories. As a non-chemist, it was tough to follow what was happening in the experiments, but now familiar with the editing process and Davy’s handwriting, there was time to reflect on the content of some of these pages while editing them. Davy uses the personal pronoun frequently – ‘I found/introduced/procured/connected’ – but regularly also drops these in his accounts of his chemical experiments. There is almost a conscious editing and removal of the self. This fits the narrative Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison give in Objectivity (2010). It is in the mid-nineteenth century that they trace the rise of ‘mechanical objectivity’, which resists the ‘temptation of the aesthetic’ to be ‘free of human interpretation’ (Daston and Galison 2010: 27, 120, 131). While Davy precedes this by a couple of decades, the formal contrast in his poetics and his scientific note-taking foreshadow this move in science.

Editing the transcriptions of Davy’s notebooks has been a fascinating experience. As well as developing skills in editing manuscripts and working with volunteer-produced transcriptions, it has been a pleasure to ponder on the content of Davy’s notebooks. What these examples of Davy’s notebooks show us is that science is not confined to a lab; it can happen on the sofa, on the train, or when fishing. Davy can teach that science and poetry – the act of his imagination – are deeply connected.

The Davy Notebooks Project team are very grateful to Alexander for his excellent work, and to UCL and STS for making it possible.