The 4th of September this year will mark precisely 200 years since continuous motion was first produced by the interaction of electricity and magnetism. In the basement laboratory of the Royal Institution that day Michael Faraday (1791-1867), just about to turn thirty, placed a permanent magnet vertically in a bowl of mercury as shown in his drawing of the experimental arrangement (fig. 1). Into the bowl he hung a piece of wire from a hook and when he passed an electric current through the mercury and the wire, the wire began to rotate around the magnet. Faraday called this novel phenomenon electro-magnetic rotations while others, with some exaggeration, have declared it to be the first electric motor.

Fig. 1: Faraday’s experimental arrangement

At one level this can be, and has been, read as a straight-forward experimental discovery in the physical sciences. But all scientific research, experimental, theoretical, observational, takes place in a plethora of intersecting, sometimes conflicting, contexts. This experiment of Faraday’s was no exception and tracing its history through publications, paper drafts, letters, and notebooks (alas in this case not those of the former Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution Humphry Davy (1778-1829)) reveals a story of scientific jealousy and rivalry. Davy had appointed Faraday as the Royal Institution’s laboratory assistant early in 1813, but, as we shall see, by the 1820s had developed feelings of jealousy about Faraday’s increasing success, probably on both psychological grounds and on the complex political situation in the scientific community.

In scientific terms the discovery led quickly in 1822 and 1823 to a major row between Faraday and André-Marie Ampère (1775-1836) about the interpretation of the phenomenon. Their argument was instrumental in confirming Faraday’s view of the limited usefulness of mathematics in science and in moving him away from a Newtonian conception of the world to eventually formulating his field theory, one of the cornerstones of modern physics. But the controversy also prevented Ampère realising that he had observed electro-magnetic induction in 1822 and although he tried to retrospectively claim credit after Faraday discovered it in 1831, he did not convince anyone and indeed by then had forgotten the original circumstances that prevented him then from appreciating the significance of what he had seen.

So how did Faraday come to make this significant discovery? At the end of September 1820, the Annals of Philosophy provided a translation (from Latin) of the paper published earlier in the year by the Danish savant Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851) in which he announced his discovery of electro-magnetism. All over Europe chemists and natural philosophers turned their attention to this wonderful new phenomenon. Davy was in the North of England when the paper was published, so probably didn’t read it until he returned to London around 10 October. However, he immediately set to work and Faraday recorded his presence in the Royal Institution’s basement laboratory in the ensuing week. On the 19th Davy wrote to his brother telling him that he was working so much on electro-magnetism he was postponing his intended trip to Penzance to see their mother. To his wife (in Paris) he mentioned his researches requesting that she not tell any Frenchman about them. For the rest of the month Davy continued his experimentation in both the Royal Institution and the London Institution which had a powerful new battery; Faraday was present on many of these occasions and took notes.

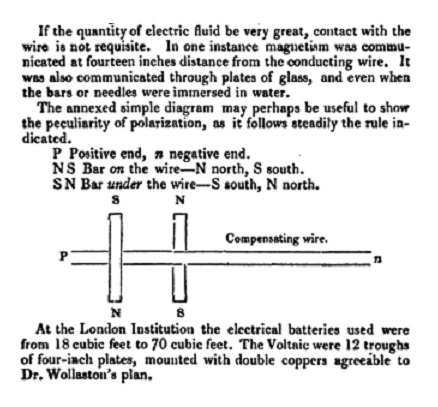

Just under a month later Davy sent a paper to his friend and acting President of the Royal Society of London, William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) describing his results. In the form of a letter (in Faraday’s hand illustrating the power that Davy still wielded at the Royal Institution), Davy announced his findings that metal could be magnetised by passing an electric current in a nearby wire and that the polarisation of the magnet produced depended on its relative position to the wire. This arrangement was illustrated in the report published in the Philosophical Magazine (fig. 2), but not in Davy’s Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London paper. He concluded by conjecturing that the earth’s magnetism was caused by electric currents as were the aurora.

Fig. 2: From the Philosophical Magazine

Davy succeeded Wollaston as President of the Royal Society of London on 30 November 1820 and quickly realised the enormous amount of work the position entailed about which he complained. So, it was not until February 1821 and again in May that he was able to resume work on electro-magnetism once again at the Royal and London Institutions with Faraday and Wollaston occasionally present. At some point during the summer Faraday accepted the invitation from the newly appointed editor of the Annals of Philosophy and old friend Richard Phillips (1778-1851) to write a review article discussing the now considerable literature on electro-magnetism. The first two parts published in September and October were anonymous which may suggest a degree of nervousness on Faraday’s part about what Davy (away in the North again) might think.

To understand what had been written about electro-magnetism Faraday decided to repeat (insofar as the descriptions permitted) the experiments that had been made by savants such as Oersted, Ampère, François Arago (1786-1853), etc., as well as Davy and Wollaston. It was in this context of making such experiments in a series commenced on 3 September 1821 that the following day Faraday discovered electro-magnetic rotations. He was fully conscious that this was a major discovery needing publication as quickly as possible. The Quarterly Journal of Science edited by Davy’s successor at the Royal Institution, William Thomas Brande (1788-1866), published by John Murray (at the other end of Albemarle Street), had a semi-detached connection with the Institution. In Brande’s absence Faraday had been left to look after the Journal and so took advantage to publish his paper on electro-magnetic rotations in the October issue.

Faraday then went on holiday to Ramsgate with his new wife at roughly the same time as Davy returned to London with toothache and marital problems, so it may be reasonably adduced that he was not in the best frame of mind to appreciate Faraday’s actions. On his return to London, Faraday found that rumours were circulating that he had not properly acknowledged the electro-magnetic work of Davy and Wollaston and specifically of plagiarizing the latter. Alarmed, Faraday sought a meeting with Wollaston who told him loftily he had no strong feelings on the matter but invited him to call. Whether that meeting happened or not is not clear, but things seem to have calmed down.

However, at a meeting eighteen months later of the Royal Society of London on 6 March 1823, during the reading of another of his papers on electro-magnetism, Davy from the President’s chair,

thought it right to state a circumstance, which, though known to many Fellows of the Royal Society [of London], was not generally understood: this was, that we owe to the sagacity of Dr. Wollaston, the first suggestion of electro-magnetic rotation; and that, had not an experiment on the subject, made by Dr. W. in the laboratory of the Royal Institution, and witnessed by Sir Humphry, failed, merely through an accident which happened to the apparatus, he would have been the discoverer of that phenomenon.

Although in his published paper he softened this, slightly, the damage had been done. Presumably as a response Phillips immediately set about organising Faraday’s election to Fellowship of the Royal Society of London which was publicly, though unsuccessfully, opposed by Davy, leading to a complete breakdown in their personal relations. Davy turned to exploiting Faraday’s undoubted scientific and administrative skills by, for example, getting him to be the first (unpaid) Secretary of the Athenaeum Club and working for most of the second half of the 1820s on the project to improve optical glass. At the time Faraday regarded this as a complete failure and waste of his time, but modified that view following his using a piece of glass he had made then to discover in 1845 the magneto-optical effect, allowing him to finally formulate his field theory.

When Faraday had first been in contact with Davy about pursuing a career in science, he claimed he had been full of idealism ‘of the superior moral feelings of philosophic men’ to which Davy responded that ‘the experience of a few years … [would] set me right on that matter’. This was written after Davy’s death, so might well reflect the experience that Faraday had undergone of working for Davy and observing at close hand his problematic career trajectory, rather than anything said in 1812 or 1813. That Faraday regretted what had happened with the outcome of electro-magnetic rotations, his election to the Royal Society of London, and a few other matters, is clear from his comment in 1838 to the Chancellor of the Exchequer that of all his honours ‘One title, namely that of F.R.S.[L.] was sought and paid for’.

—

Notes

Davy’s letter to his brother of 19 October 1820 and that to Wollaston (in Faraday’s hand) of 12 November 1820 are respectively Letters 743 and 747 in volume three of Davy’s Collected Letters.

Davy’s comments to the Royal Society of London on 6 March 1823 were reported in Annals of Philosophy, xxi (1823), 303-4.