Dear all,

We’re very pleased to announce that our project will soon be live on Zooniverse. Below is a short piece on Davy’s early life – the period we concentrated on during the pilot project in 2019 – focusing largely on notebook RI MS HD/13/C. It recounts some of the findings of the pilot, as well as looking forward to the full project that will be launching in the coming days.

We’re always very keen to hear from anyone who’s interested in our project, or Davy, or literature and science and/or the history of science more generally. If you’d like to get in touch with the project team, please see our Contact page. You can also join the discussion through our Talk pages on Zooniverse.

Best wishes, and happy transcribing!

Andrew Lacey

* * *

Davy at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century and Now

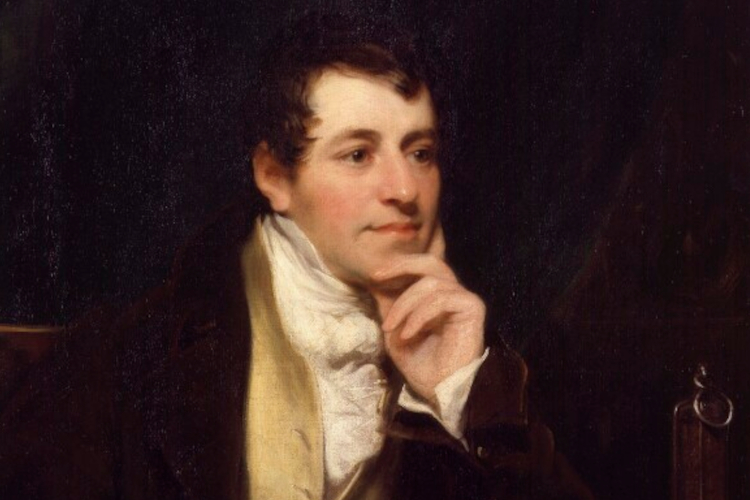

Portrait of Davy by Thomas Phillips, 1821 (National Portrait Gallery, NPG 2546. Reproduced under the terms of CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

In 1801, Humphry Davy was in his early twenties. In September 1800, hinting at the start of the rise that would see him, eventually, occupy the President’s chair of the Royal Society, he wrote to his mother, reassuringly, ‘my future prospects are of a very brilliant nature’. By the spring of the following year, he had been appointed lecturer at the recently founded Royal Institution (RI), where, over the next decade, he would undertake his most important chemical work.

Davy’s achievements while at the RI, which took as its mission ‘diffusing the knowledge, and facilitating the general introduction, of useful mechanical inventions and improvements, [and] teaching, by courses of philosophical lectures and experiments, the application of science to the common purposes of life’, were significant and numerous. Alongside giving the lectures for which he became renowned, he isolated seven chemical elements (magnesium, calcium, potassium, sodium, strontium, barium, and boron), and established the elemental status of chlorine and, shortly after resigning from his professorship at the RI, iodine. Later, as the foremost man of science in Britain, he would, in 1812, be knighted by George, the Prince Regent. Still later, in 1818, Davy would be made a baronet in recognition for his work (from 1815 onwards) on the miners’ safety lamp.

So far, so brilliant, we might say. But when Davy first arrived in London, there was some consternation as to his suitability for the lecturing role he had been recommended for, as a newly published biographical account, probably written by Davy’s friend Thomas Richard Underwood, explains:

The Count [Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford; founder, with Sir Joseph Banks, of the RI] and the Managers were struck most unfavourably with [Davy’s] infantine face, natural awkwardness, & Cornish accent … All [that Davy’s friends, who had recommended him for the role] could obtain was that he should deliver a lecture on Galvanism in a comparatively small room on the ground floor of the Royal Institution …

This room, by the exertions of the party, was crowded to suffocation & graced by the presence of many of the youthful females of that party and among them several of the highest rank in the country; they were captivated by his pretty face, simplicity of manner, and most romantic poetical language. While the men were struck with the novelty of the subject (it being the first lecture on Galvanism ever given in London) and of which he evinced himself completely master.

The RI building on Albemarle Street, c. 1838, by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd (in public domain)

Rumford’s and the Managers’ early doubts quickly evaporated, as Underwood confirms: ‘[Davy’s] success was such that he was instantly engaged at a higher salary than his friends had demanded & desired to repeat the lecture the next day … From that moment he became the most popular lecturer ever heard in London’. The young Davy, though no doubt flushed with success, had not yet become vain and arrogant, charges levelled against him (quite fairly, in some cases) in later years: in his private correspondence, Davy records that he was ‘was very much flattered to find the theatre overflowing…’ in January 1802, and candidly observes, in June of the same year, that ‘my labours in the theatre of the Royal Institution have been more successful than I could have hoped…’.

The early years of the nineteenth century were, by any measure, golden ones for Davy. His mind teemed with new ideas, theories, and experiments, intermixed with the new impressions of the ‘great hot-bed of human power’ (letter to Thomas Charles Hope, June 1801) of the capital, and he relished all of the new experiences (and, as we can also glean from his letters, temptations) that had opened up to him as a rising star in the metropolis. His notebooks of the period grant us a privileged, intimate insight into his private thoughts. One such notebook, RI MS HD/13/C, held in the archives of the RI and recently transcribed in full, for the first time, by volunteers of Zooniverse, the world’s largest and most popular platform for people-powered research, shows us the activity and, perhaps most strikingly, the fluidity of Davy’s mind at the time.

There are several poems in this notebook, such as ‘On Breathing the Nitrous Oxide’, which details Davy’s self-experimentation with what, since his first inhalation of it at a time when doing so was thought to be fatal, has commonly become known as ‘laughing gas’ (‘My bosom burns with no unhallowed fire / Yet is my cheek with rosy blushes warm / Yet are my eyes with sparkling lustre filled…’), and ‘The Spinosist’, a reflection, engaging with the ongoing debates, drawing on classical sources, on atomism of the period, on the cyclical nature of life (‘All, all is change, the renovated forms / Of ancient things arise and live again…’), that, as generally discrete and coherent works, are gradually becoming more well-known.

Other poems exist in this notebook in tantalising outline plan form only, such as Davy’s projected experiment in the Oriental tale, ‘Moses’ (‘Moses in wandering in the desart / falls down the cataract meets / with Miriam, she tells him of / a light of glory surrounding his / body believes himself under / the immediate inspiration of / the deity…’). Although only the skeleton of the (presumably intended to be epic) poem ‘Moses’ exists, it at least demonstrates the young Davy’s poetic ambition, which was seldom lacking.

RI MS HD/13/C, p. 17: ‘Moses: Book I’ (click to enlarge)

In notebook 13C, poems jostle for space with prose, much of it philosophical. In his manuscript, Davy sketches out a plan (which might put us in mind of Wordsworth, whom Davy first met in 1804) to write on the nature of genius (‘description of the / infant [?organised] so as to be / capable of genius…’), the state of chemical knowledge of the day (‘All our classifications are in fact artificial / nature does not know them & in fact / will not submit to them. but it is / of use to form analogies…’), and, perhaps most significantly, on the role that the sciences and the arts might play together in accomplishing ‘great’ objects, such as the ‘prosperity’ of nations:

we may hope

that a new spirit has

arisen that a new feeling

has pervaded the public

mind; it now seems to

be generally felt that

great & powerful exertions

in the sciences & the arts

can only be produced by

a spirit that may

be called national…

Davy’s reflections on the need for the free exchange of ideas, for collaboration across disciplinary boundaries (however real or imagined they may be), and for joined-up critical thinking among all who seek to earnestly enquire into the nature of the world remain, in this age of climate emergency, rapidly developing global health crises, and the proliferation of easily accessible misinformation, startlingly relevant.

Davy’s turn, in 13C, to a discussion of ‘national superiority’ hints at some of the more troubling content to be found in his notebooks – eight of which have so far been transcribed by Zooniverse volunteers – such as his use of crude racial stereotypes in the earliest of the pilot notebooks, RI MS HD/13/F, which dates from 1795-6.

Davy’s rash, prejudicial speculations, such as those on the relative influence of the climate on ‘the Regions of Ignorance & [?Barbarity]’ as contrasted with ‘the More enlightened & polished Nations of Europe’, stand in stark contrast to the careful, methodical approach he took to his chemical work, evidence of which nestles, sometimes jarringly, alongside fragments of his poetry and prose. Results of his laboratory work of the period, notes and figures, mainly relating to galvanism and tanning, compete for page-space with sketches of chemical apparatus, technical diagrams, and curiously disembodied faces in profile.

Despite his ‘mastery’ of the public lecture form, Davy’s notebook also contains reminders that, as a young man finding his feet in a strange new world, his self-confidence – which, later, would occasionally boil over into high-handedness and general unpleasantness, such as in his epistolary assessments, only very recently brought to light, of his main safety-lamp rival, the Northumberland-born mechanic George Stephenson – was still, in parts, fragile.

At one point in notebook 13C, Davy drafts a letter to be sent back home to an M. Dugart in Penzance, a French immigrant and teacher, whom he wishes to teach his younger brother, John. (Davy’s father, Robert, had died in 1794, leaving the family in debt, and, as oldest son, Davy often found himself playing the role of father to his siblings; in John’s case at least, Davy did a fine job, as his brother became an eminent army doctor, and a Fellow of the Royal Societies of London and Edinburgh).

RI MS HD/13/C, p. 116 (inverted): ‘My dear Sir, / The little boy / who brings you this letter is / my brother…’ (click to enlarge)

At another point, Davy drafts an appreciative letter to his former guardian, and a crucial formative influence in Cornwall, Dr John Tonkin. The older, more confident Davy seldom felt the need to draft letters; a notable exception is the letter he wrote (but perhaps never sent) to the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, in 1815, in which, seemingly stoked with nationalistic fervour, he railed against the French after Waterloo, apparently thirsty for harsher treatment of the ‘enemy’:

I am convinced that there will be a most severe disappointment, a great fermentation in the public mind; & a state of feeling dangerous to the government & to the tranquillity of the country; if the glorious fortune of the present moment is not applied in giving permanent peace to Europe by destroying the military power of France diminishing their territory & resources.

Davy’s collected letters have recently been published in an authoritative edition (The Collected Letters of Sir Humphry Davy, published in four volumes by Oxford University Press), long in the making. Already, our understanding of Davy has been reconfigured by this work: the previously unpublished letters on the so-called ‘safety lamp controversy’ clearly show a far more prickly, insecure side to Davy than more selective biographical work to date has allowed. His notebooks, however, remain a largely untapped resource. This will change, as the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded Davy Notebooks Project is due to launch, in full format, in June 2021.

Building on the successful pilot project (also funded by the AHRC), the Davy Notebooks Project will crowdsource full transcriptions, using Zooniverse, of the remaining seventy-or-so Davy notebooks held in the RI and Kresen Kernow (‘Cornwall Centre’). Anyone can contribute a transcription, however short, and, eventually, this work will lead to the full publication online, on the free and open-access Lancaster Digital Collections platform, of all of Davy’s notebooks. The project team also know of the existence of three ‘lost’ notebooks, containing material on fish and angling; whether they can be located within the three-year project timeframe remains to be seen.

Enticingly, the pilot project findings suggest that Davy may well be a little more unguarded in his notebooks than in his letters: a letter, after all, always presupposes a second reader; the same does not necessarily apply to a notebook. When the transcription and editing of the collected notebooks is complete, our understanding of Davy – the most effective experimentalist and most popular public communicator of science of the early nineteenth century in Britain, but a man of complex, and, at times, distinctly flawed, character – will be reconfigured once again.