Welcome to The Ruskin’s blog: the place for articles, stories and views from The Ruskin.

We are returning to the blog for our new season’s programme, Tomorrow’s World Today: Ruskin, Art and Science. This summer, The Ruskin has partnered with the Royal Society for the 2021 edition of Summer Science, a week-long festival celebrating cutting edge UK science.

From 8th July, explore two digital exhibitions co-curated by The Ruskin’s Director Professor Sandra Kemp and the Royal Society, Head of Library, Keith Moore. Both exhibitions are part of The Ruskin’s combined research and exhibition programmes on Google Arts and Culture and introduced in the post Cloud Perspectives, written by Sandra Kemp, for the Royal Society blog.

Read the blog post Cloud Perspectives here.

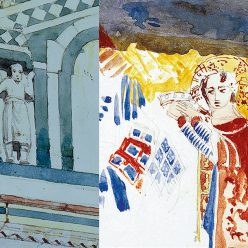

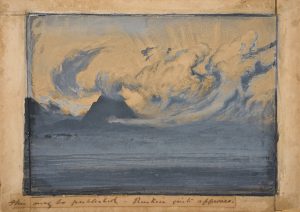

From the first photographic images of glaciers, to experimental studies of aerial perspective, to Ruskin’s classification system for Alpine geology, Painting with Sunlight: Ruskin and Science highlights drawings, paintings and daguerreotypes from Lancaster University’s Ruskin Whitehouse Collection, alongside works by Victorian scientists from the Royal Society archive.

Explore Painting with Sunlight: Ruskin and Science here.

Ruskin attended the Royal Society Soirée in 1862 for astronomer Warren de la Rue’s lecture on the total eclipse of the sun. The Royal Society Soirées: Highlights from the Summer Science Exhibition looks back to the origins of the Summer Science festival in the interplay of the arts and sciences at these spectacular displays, from the 1840s to-date.

Explore The Royal Society Soirées: Highlights from the Summer Science Exhibition here.

These exhibitions open our year-round programme of digital exhibitions and events. Join us in October for the Library and COP26 Festivals at Lancaster Unviersity. Encompassing exhibitions, events, research and learning, Tomorrow’s World Today will explore Ruskin’s farsighted contribution to scientific innovation, and his contemporary relevance to pressing social, cultural and environmental concerns. Ruskin was a polymath and his works capture the explosion of knowledge resulting from the 19th century voyages of discovery, which shaped our scientific understanding of the natural world today. Two years in the making, the programme builds on the 2019 exhibition Ruskin: Museum of the Near Future, which you can revisit via virtual tour.

This blog is the place where we’ll share perspectives on Ruskin and science: with articles and ‘think-pieces’ from our speakers and workshop participants, views from contemporary artists responding to Ruskin’s art and ideas, and in-depth explorations of individual pieces in the collection, from new readings of iconic works, to new research into parts of the collection that have not been widely studied or displayed to-date. Our next blog is on a work that has remained unidentified until now, in partnership with the Natural History Museum.

Keep in touch by subscribing to our newsletter, and following us on Twitter and Instagram. You can explore the collection in our Google Arts and Culture exhibits; Recover and Reimagine: Lancaster’s Future Heritage, an online exhibition co-produced with Lancaster’s museums for International Museum Day; and through the collection pages on our website. We invite you to browse the catalogue, and tell us what you’d like to know about Ruskin and scientific innovation: you may find it featured in Tomorrow’s World Today.