Our latest blog post comes from Professor Laurence Roussillon-Constanty (Université de Pau et des pays de l’Adour). The post, which follows Laurence’s paper given as part of the Ruskin Beyond Britain series, will be extended for publication in the next issue of The Ruskin Review.

From Ruskin’s first visit to France with his parents in 1825 to his final continental tour of 1888, one gets a sense that he always went through France on his way to somewhere else, somewhere beyond: beyond to Switzerland, where he thought about settling down for a while or beyond to Italy and Venice, his second home. And yet reconsidering Ruskin’s mention of French topography and natural sites reveals how much its contrasting reliefs came to symbolize and embody Ruskin’s artistic and poetic vision of landscape – a vision grounded in the visible (an insight) but later transformed into an inscape (through hindsight). Beyond the historical monuments of Northern part of France and Notre Dame-de Paris that certainly were for Ruskin a well-known source of inspiration, other and perhaps less prestigious parts of France thus gradually became significant sites whose presence can be traced in filigree in his multiple writings from his diaries to his art criticism.

Among those places, in my seminar paper, I chose to focus on two particular sites that I argued were foundational not only in Ruskin’s perception of France but also on his conception of the relation between nature and art: The Grande Chartreuse, in the French Alps, and the Jura mountains – two focal points that purposefully offered a contrastive view of Ruskin’s French experience.

The first part of my investigation was devoted to the Romantic lens through which Ruskin viewed parts of the French landscape and architecture and demonstrated the parallel features between his representation of the country and the popular illustrated travel guides published in France throughout the nineteenth century and whose visual impact would have been great not just on Ruskin but on all the English travellers at the time.

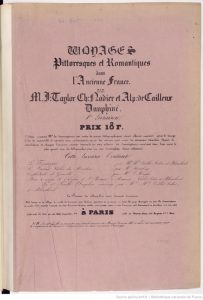

Among them, the most important one was the monumental edition of Baron Taylor’s Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’Ancienne France, a hallmark of romanticism comprising a volume dedicated to the Dauphiné (published between 1843 and 1854) and another one dedicated to the Jura (published between 1828 and 1829).

In my understanding, looking at those earlier Romantic descriptions of the Chartreuse and the Jura in relation to Ruskin’s travel through the Continent first helps us situate his experience within a European context by showing his aesthetic alignment with earlier British poet-travellers such as Lord Byron, Shelley and Wordsworth and French “poètes-promeneurs” such as Rousseau. it also invites us to think about landscape as a transformative experience that may resurface many years on in later work, influencing both content and form.

In my contention, Ruskin’s early visual impressions of the Grande Chartreuse and the “mont cachés du Jura” can thus be said to have mapped out “en creux” Ruskin’s visual imagination and contributed to his singular appreciation and later rendering of landscape in drawing, writing and even teaching. While hidden from immediate view compared to the more salient lines of the Montblanc, embedded in memory and probably tied in with early romance, those early souvenirs of picturesque France could ultimately be interpreted as a marker of Ruskin’s deeply-rooted attachment to France as Scotland’s age-old ally and companion land.

Professor Laurence Roussillon-Constanty is Professor in English Literature, Art and Epistemology at the Université de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour (France) and a Member of the Research Group ALTER. She is President of the French Victorian Society (SFEVE) and a Companion of the Guild of Saint George. She is the author of Méduse au miroir: Esthétique romantique de Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Grenoble: ELLUG, 2007) and co-editor (with David Clifford) of The Rossettis then and Now: Cosmopolitans in Victorian London (London: Anthem Press, 2003). She also co-authored a translation into French of a selection of texts from John Ruskin’s Modern Painters (Pau: PUP, 2006).