In this post, Dr Barnita Bagchi discusses her British Academy Visiting Fellowship at The Ruskin, ‘Transcultural Utopian Imagination’.

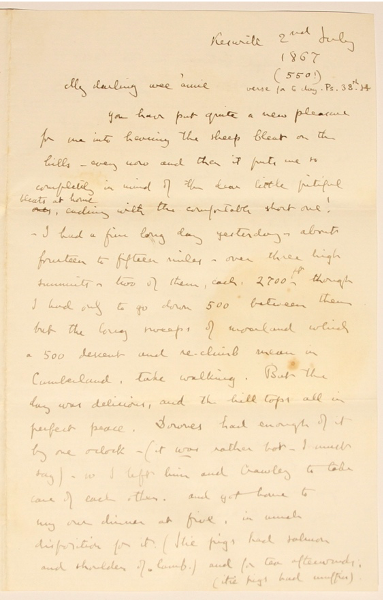

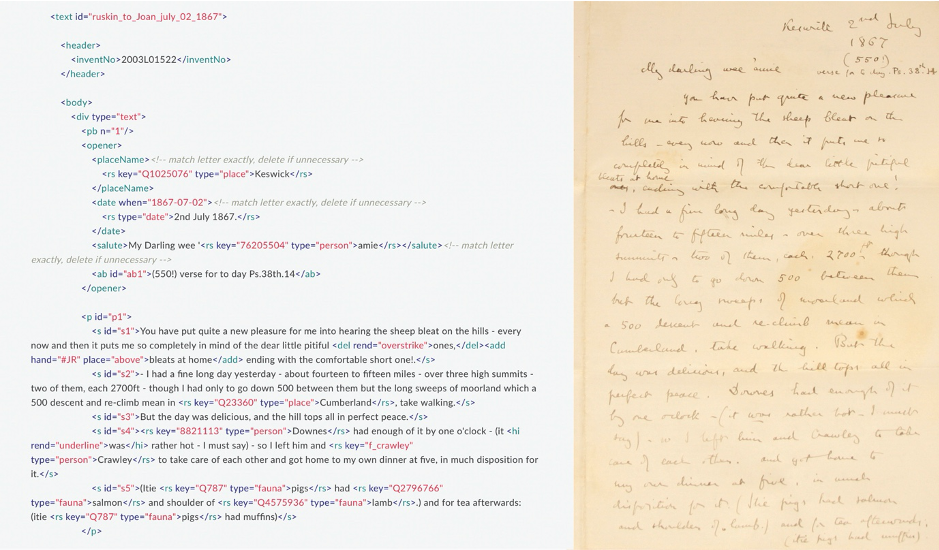

My British Academy Visiting Fellowship, held for two months at The Ruskin – Library, Museum and Research Centre, Lancaster University, from late August to late October 2018, researched transcultural utopian imagination in early 20th-century South Asia. At the centre of my research were the South Asian, Indian, and transcultural poet, educator, and community-builder Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), his friend and associate, anti-colonial politician and social experimenter M. K. Gandhi (1869–1948), and their mutual friend, British Christian anti-colonial and social activist, pacifist, and missionary C. F. Andrews (1871–1940). John Ruskin, whose Unto this Last influenced Gandhi, also figured prominently. I argue that the visits of Tagore and Gandhi to England in 1930 and 1931 respectively manifest and illuminate Indo-British entanglements in social dreaming or utopian imagination and experimentation.

The Ruskin, the Institute for Social Futures, and the Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University all supported my application, and I was hosted by the Ruskin, in an institutional environment which was supportive and stimulating.My hosts and I were delighted that during this fellowship, we could co-organise a conference on Transcultural Utopian Imagination and the Future: South Asia, Britain, and Beyond, on 11 October 2018, at The Ruskin. Speakers at the symposium included Sandra Kemp, Carlos Lopez-Galviz, Lynne Pearce, Rebecca Braun, Sangeeta Datta (filmmaker, curator, director, academic, singer, who gave a keynote speech), Monika Buscher, Nicola Spurling, and northern England-based creative writers Shamshad Khan and Qaisra Shahraz. I am guest editing a special issue of Utopian Studies, a leading journal in the field, entitled ‘The Prospective Memory of the Future’ as the key output of my Fellowship.

I went to Darwen, Lancashire, during the period of my fellowship. Darwen prospered due to the spinning and weaving of cotton. Yet cotton did not grow in Lancashire. The American Civil War increased Britain’s dependence on cotton from India and Egypt, and this cotton was processed industrially into cloth in Darwen and other cotton towns of Lancashire. During my stay in Lancashire, I also went to Edgworth, near Darwen, where I found myself standing outside Brandwood Fold. Edgworth used to be industrial, a hub of cotton manufacture. Lancashire cotton manufacturer James Barlow was born in this rustic fold, the son of a weaver, Thomas Barlow. James (1821–1887) later lived at Greenthorne, Edgworth, which Gandhi would visit in 1931. The Barlow family became wealthy and well-known philanthropists. They financially supported charities connected with the Methodist church, most notably including the National Children’s Home and Orphanage at Crowthorn, the Barlow Institute, which they founded in 1909.

Edgworth, now in the borough of Blackburn with Darwen, Lancashire, looks similar, to an outsider’s eyes, to the villages idealised by Romantics in their critique of industrialism. James Barlow was born in a family that wove and spun cotton in the pre-industrial handloom manner. Brandwood Fold was one among a number of folds, formed in the seventeenth century through the enclosure of a farmstead and associated cottages. James’s daughter Annie Barlow (1863–1941), whom the family trade in Egyptian cotton led to a passion for Egyptology, and who was also a great philanthropist, hosted Gandhi in 1931.

Gandhi worried representatives of the Lancashire cotton industry, which was in decline then for many reasons. They were concerned that an Indian boycott of manufactured Lancashire cotton was contributing to the decline of the UK industry. (In fact, other factors, not least the ascendancy established by Japanese-manufactured cotton by the early 1930s, were far more important for that decline.) Gandhi, of course, did not love machine-spun cotton: he campaigned for the widespread crafting and use of village handloom cotton, and the spinning-wheel or charkha with which he himself and millions of his followers spun coarse cotton, khadi, was an object that was a concrete image of the commitment to village India, to the artisanal, to the manual, to craft, and to the beauty of the handmade product. At Greenthorne, as in nearly every place he visited, Gandhi used the charkha.

I also visited the estate of Brantwood, on the shores of Coniston Water, in Cumbria, where John Ruskin lived in the latter part of his life, a sublime landscape of mountains and water, redolent of Romantic expressive aesthetics and the pastoral. My time in northern England illustrated to me how in Lancashire and in Cumbria, places are often fulcrums both for the industrial-urban and the pastoral-rural. Both Tagore and Gandhi were acutely aware of the deindustrialization of India under British colonialism, which took place through squeezing out handwoven cloth produced locally in India in favour of influxes of British-manufactured cotton that were exempt from or had very low tariffs. Tagore and Gandhi had somewhat different views about the presents and futures they wanted for India. Tagore was more positive about industrial society. They both however remained committed to micro-utopian experimentation, with handicrafts and labour being particularly key to Gandhi’s ideals. In this regard, John Ruskin’s Unto This Last (1860), as Gandhi famously articulated in his autobiography, was a major influence:

It was Ruskin’s Unto This Last. The book was impossible to lay aside, once I had begun it. It gripped me. Johannesburg to Durban was a twenty-four hours’ journey. The train reached there in the evening. I could not get any sleep that night. I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book.

This was the first book of Ruskin I had ever read. During the days of my education I had read practically nothing outside text-books, and after I launched into active life I had very little time for reading. I cannot therefore claim much book knowledge. However, I believe I have not lost much because of this enforced restraint. On the contrary, the limited reading may be said to have enabled me thoroughly to digest what I did read. Of these books, the one that brought about an instantaneous and practical transformation in my life was Unto This Last. I translated it later into Gujarati, entitling it Sarvodaya (the welfare of all).

I believe that I discovered some of my deepest convictions reflected in this great book of Ruskin, and that is why it so captured me and made me transform my life. A poet is one who can call forth the good latent in the human breast. Poets do not influence all alike, for everyone is not evolved in an equal measure.

The teaching of Unto This Last I understood to be:

-

-

-

- That the good of the individual is contained in the good of all.

- That a lawyer’s work has the same value as the barber’s, inasmuch as all have the same right of earning their livelihood from their work.

- That a life of labour, i.e., the life of the tiller of the soil and the handicraftsman, is the life worth living.

-

-

The first of these I knew. The second I had dimly realized. The third had never occurred to me. Unto This Last made it as clear as daylight for me that the second and the third were contained in the first. I arose with the dawn, ready to reduce these principles to practice.1

I’d like us first to focus on the medium of the book, studied on that very modern medium of mobility, the train. Gandhi was in South Africa in 1904, and Unto This Last was gifted to him by Henry Polak (1882–1959), his British-Jewish friend, and later editor of the Indian Opinion. The transnational and transcultural dimensions are evident. It is also notable that Gandhi learns from a ‘poet’, from the domain of aesthetics, ‘through the magic spell of a book’, that all work is or should be viewed with equal value and dignity. Gandhi also saw Tagore, like Ruskin, as above all a poet: the imagination remained very important to Gandhi, who saw himself, in contrast, as the experimenter in and seeker after Truth. The Beauty-Truth relationship is re-parsed again and again in the social dreaming of Tagore and Gandhi. In learning that a life of labour, of the tiller and the handicraftsman, is the life worth living, the recoil from machinic, urban, industrial life is implicit.

Yet Gandhi worked in his political career with urban working classes, too, not least in his native province of Gujarat, which was home to leading Indian cotton mills: in March 1918, he led a non-violent strike based on the principle of Satyagraha or civil disobedience in the cotton mills of Ahmedabad, one in which he went on hunger strike, with a resolution in which workers’ demands for higher pay were largely conceded by mill-owners. So, it is perhaps not surprising that Gandhi’s visit to the Lancashire cotton workers and mill owners was so cordial. In late September 1931, he visited Lancashire, first meeting with representatives of cotton industry at Edgeworth and Darwen. On 26 September 1931, he received a deputation of unemployed workers at Spring Vale Garden village, Darwen. Having spoken on Lancashire’s unemployment problem, having received deputations from weavers’ associations and unemployed workers, and having spoken to journalists, Gandhi left Lancashire.

Readers will find out more about the resonances between British and Indian utopianists that I uncovered in the published output from my British Academy-funded project, but the larger point that I want to make here is that the Indo-British utopian entanglements I studied complicate reductive binaries between urban and rural, industry and handicraft, ‘West’ and ‘East’, Britain and India, with the aesthetic and the ethical continuously entangled, in visions of social futures in which cooperation, solidarity, and fellowship were interwoven, to use an image from handicrafts and from the imaginative domain. The Ruskinian resonances echo through to our times, rippling across to the futures we attempt to build today in our larger social crisis unleashed by a pandemic. Andrews, Tagore and Gandhi would, I believe, remind us again today of the truth of John Ruskin’s words: ‘There is no wealth but life.’

1M.K. Gandhi, An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth, trans. by Mahadev Desai, 2nd edition (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press, 1940), pp. 364–65.

___________

Dr Barnita Bagchi is a faculty member in Comparative Literature at the Department of Languages, Literature, and Communication at Utrecht University. Her research investigates transcultural utopian imagination in early 20th century India and Britain. Her British Academy Visiting Fellowship was hosted at The Ruskin during the summer and autumn of 2018.