In this post, Dr Claire Nally (Northumbria University) reflects on the connections between Ruskin’s thought and Steampunk culture, a subject she explored as part of our recent research seminar series, Ruskin & Steampunk: Recovering Radicalism.

In The Steampunk Bible, Jake von Slatt’s article ‘A Steampunk Manifesto’ suggests that steampunk practice is a contestation of contemporary mainstream, mass–produced culture:

The only future we are promised is the one in development in the corporate R&D labs of the world. We are shown glimpses of the next generation of cell phones, laptops, or MP3 players. Magazines that used to attempt to show us how we would be living in fifty or one hundred years, now only speculate over the new surround-sound standard for your home theater, or whether next year’s luxury sedan will have Bluetooth as standard equipment.

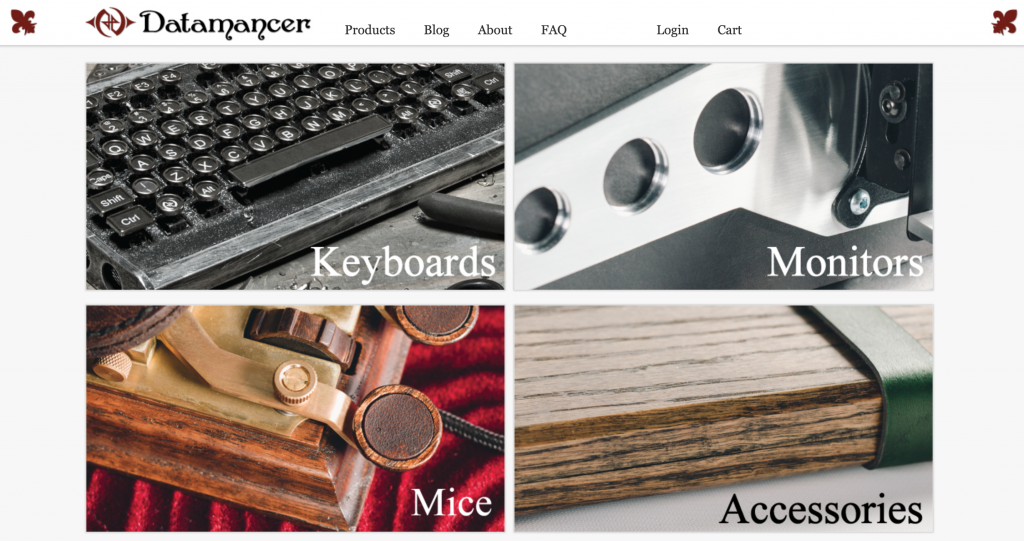

This statement of steampunk’s rebellion against the mass-produced, sleek lines of contemporary commodity culture provides a useful comparison to the ways in which the nineteenth-century arts and crafts movement can be used to read the steampunk subculture. Steampunk artists often take something from our modern-day culture, such as the computer, and retro-fit it, or imagine its aesthetic value when invested with nineteenth century images. So one famous example, a steampunk computer, may be fitted with an old typewriter keyboard for an antiquated look. Perhaps the most important example of this work is Datamancer (Richard Nagy), whose website explains:

The idea was to build a full computer station from every significant artistic decade in history. From Art Deco, to Victorian, and even back to Gothic design. It started with a Victorian style brass keyboard […] which pioneered the idea of typewriter key caps on a modern keyboard.

This combination of modern utility with historical style is a hallmark of steampunk design. These are practical everyday objects converted to a steampunk aesthetic: wood, brass, cogs, the inner working of machines.

<https://datamancer.com/>

Interestingly, many steampunked items are custom-made and marketed through the possibilities allowed by Web 2.0 sites such as Etsy’s craft community, promoting as it does an international network of small businesses and collective engagement. As David Gauntlett argues in Making is Connecting (2013):

Web 2.0, as an approach to the web, is about harnessing the collective abilities of the members of an online network, to make an especially powerful resource or service. But, thinking beyond the Web, it may also be valuable to consider Web 2.0 as a metaphor, for any collective activity which is enabled by people’s passions and becomes something greater than the sum of its parts.

So part of the idea of collectivity and subculture in steampunk is communicated via very modern technology, whereas prior subcultures, such as punk or goth, originally had to rely on analogue methods.

<https://datamancer.com/product/the-sojourner-keyboarddisplay-set/>

Other steampunk manifestos seem quite emphatically embedded in presenting a steampunk which maps an awareness of the inequalities of the past onto the present, proposing social and aesthetic reform. The Steampunk Magazine is a foundational publication in this respect. The opening article of the first issue, ‘What then, is steampunk?’ articulates this most forcefully:

We seek inspiration in the smog-choked alleys of Victoria’s duskless Empire. We find solidarity and inspiration in the mad bombers with ink-stained cuffs, in whip-wielding women that yield to none, in coughing chimney sweeps who have escaped the rooftops and joined the circus, and in mutineers who have gone native and have handed the tools of their masters to those most ready to use them.

This argument puts the injustices of Victoria’s reign – women’s rights, Empire, class distinctions, working children and poverty – at the forefront of steampunk practice, and aligns steampunk radicalism with the outsider in the nineteenth century. The ‘whip-wielding women’ (whilst being suggestively sexual), possibly refers to suffragette figures like Emily Wilding Davison, who famously attacked a vicar with a dog whip in 1913, mistaking him for the Prime Minister, Lloyd George. Sympathy with ‘mad bombers’ is likely a gesture towards anarchist agitation in the period, and perhaps specifically references the Greenwich Observatory bombing of 1894 (immortalised in Joseph Conrad’s 1907 novel, The Secret Agent). So in many ways, the magazine presents itself as an activist publication in this opening issue, and this version of steampunk is aided by its publication context, its status as an online zine, and its political content. And in addressing the production of the magazine as well as its content, we can uncover the radicalism which steampunk can represent.

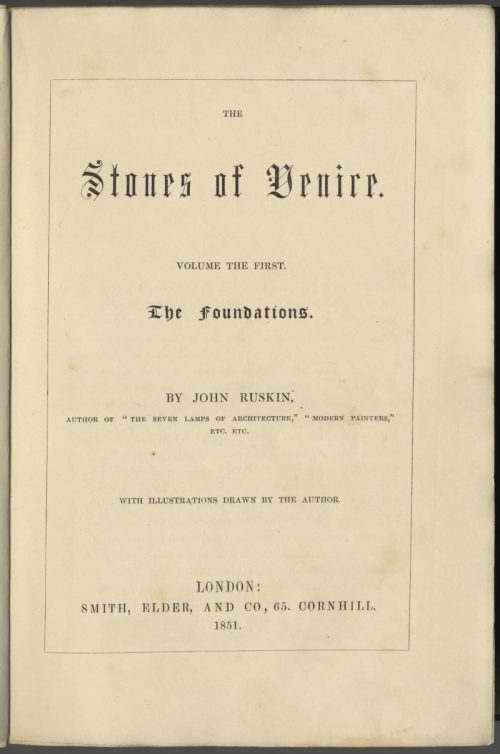

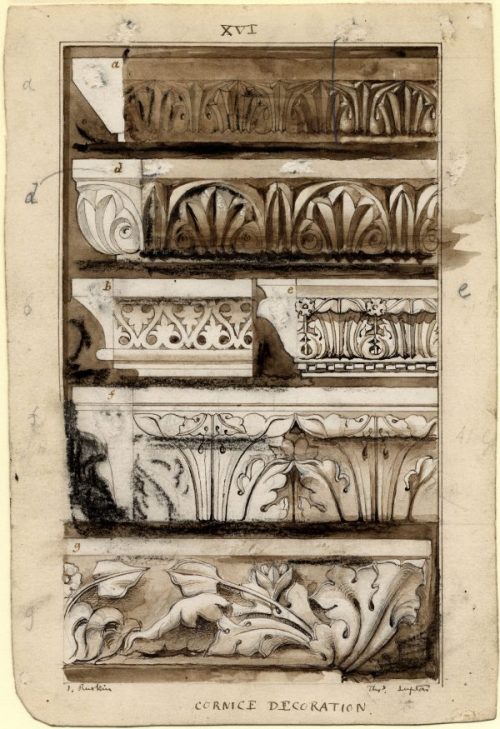

So how does steampunk correlate with the work of Ruskin? Martin Danahay’s discussion of steampunk and Arts and Crafts, as influenced by Ruskin, highlights how both ‘rejected industrialised manufacturing and emphasized a return to small-scale production of handcrafted objects.’ Much of the DIY ethics of steampunk has a similar trajectory, even if it celebrates the industrial machinery which the Arts and Crafts movement rejected. Ruskin’s comment in The Stones of Venice (1851–53), that industrial production renders the worker akin to a machine, plainly espouses artistic freedom instead of mass-produced monotony:

Men were not intended to work with the accuracy of tools, to be precise and perfect in all their actions. If you will have that precision out of them, and make their fingers measure degrees like cog-wheels, and their arms strike curves like compasses, you must unhumanize them. (10.192)

There is a tension here between such dehumanization, and the celebration of the prosthetic in steampunk performances. Steampunk arms, hands, and mechanical attachments to the body all suggest an uneasy negotiation of our relationship with machinery. But in each instance, the hallmark of the steampunk aesthetic is the imperfect, as the Catastrophone Orchestra article in The Steampunk Magazine makes clear: ‘Imperfection, chaos, chance, and obsolescence are not to be seen as faults, but as ways of allowing spontaneous liberation from the predictability of perfection.’

Danahay describes this correlation between steampunk and Ruskin’s work as the ‘as both the rejection of industrialized mass production and the promotion of humane conditions of labour’ (p. 42). These discussions of labour and exploitation, the role of technology, DIY and resistance, find a focal point in The Steampunk Magazine, which lasted for nine issues, and delivered interviews with writers, such as Michael Moorcock and Alan Moore, as well as musicians and bands. The magazine also published original fiction and poetry on steampunk themes, but a large part of the publication was comprised of non-fiction articles, including descriptions of the subculture, lifestyle advice, and hints and tips for makers and DIY practitioners (for instance, ‘It Can’t All Be Brass, Dear: Paper Maché in the Modern Home’, ‘Sew an Aviator’s Cap’, ‘Sew Yourself a Lady’s Artisan Apron’). At the heart of many articles is an incendiary plan to revolutionise society (‘The Courage to Kill a King: Anarchists in a Time of Regicide’, ‘Nevermind the Morlocks: Here’s Occupy Wall Street’, ‘On Race and Steampunk: A Quick Primer’, ‘Riot Grrls, 19th Century Style’).

One of the most compelling facts about steampunk is that despite its emphasis on material, tactile culture, its visibility online (through maker websites like Etsy, community forums such as ‘Brass Goggles’, online publications such as The Steampunk Journal, and designated groups on Facebook, among many other sites and forums) mean that steampunk’s digital footprint is extensive, as is now common to many subcultures. Indeed, in many ways, The Steampunk Magazine participates in constructing and maintaining the imagined subcultural community of steampunk. In his definitive statement on nationalism, Imagined Communities (1983), Benedict Anderson maintained that ‘[the nation] is an imagined political community […] because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or ever hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.’ These subcultural communities function in a similar way. As Danahay again remarks:

There are no steampunk communities in the sense envisioned by […] the Arts and Crafts movement. Rather, there are steampunk websites, discussion groups, and Facebook groups, as well as frequent temporary gatherings at conventions and other social events. People involved often refer to the “steampunk community,” but this term refers to purely virtual and abstract social grouping. Thanks to the Internet, those involved in steampunk can believe that they are members of a group, even if their connection remains entirely virtual. (p. 42)

In many ways, this is a navigation of Ruskin’s theorisation of guilds and workers’ collectives. In part, there is a strong sense of community in steampunk practice, but there is also the valorisation of the cult of the individual: the name of the maker, akin to a brand, also acquires visibility, as with post-romantic art and literature generally.

This context is especially important for The Steampunk Magazine, which was initially published in 2007 online and in print, and remains one of the best examples of resistant steampunk practice. The Catastrophone Orchestra and Arts Collective, publishing in Issue 1 of The Steampunk Magazine, suggests that ‘Steampunk rejects the myopic, nostalgia-drenched politics so common among “alternative” cultures […] Too much of what passes as steampunk denies the punk, in all its guises.’ This also summarises the ethos of the magazine very effectively. As a manifesto to steampunk practice, this perspective neatly situates itself against an uncritical nostalgia which replicates the Victorian age without any political critique. Relatedly, in some ways, steampunk more generally also carries the implicit burden of Ruskin’s critique of the nineteenth century. Steampunk has much to say about aesthetics in the contemporary moment: how we relate to machinery, the status of the individual in contemporary culture, and the ways in which subcultures engage with these key cultural themes. We might also say that in dialogue with historical figures like Ruskin, steampunk acquires a new level of depth and complexity.

__________

Dr Claire Nally is an Associate Professor of Modern and Contemporary Literature at Northumbria University, UK. She researches Irish Studies, Neo-Victorianism, Gender and Subcultures. She has published widely on goth and steampunk subcultures, and her most recent monograph is Steampunk: Gender, Subculture and the Neo-Victorian (Bloomsbury, 2019).