This blog, by Rebecca Mitchell, University of Birmingham, draws on new research to reveal a previously undocumented link between John Ruskin and Constance and Oscar Wilde.

Oscar Wilde’s connection with Ruskin is well known but surprisingly under-explored.[1] One famous episode from their shared past, a story on which Wilde dined out for decades, was the young man’s participation, while an undergraduate at Oxford, in Ruskin’s Hinksey road effort. But the Slade Professor’s influence was by no means confined to Wilde’s Oxford years, and scholars including John Unrau have called for more attention to be paid to the role that Ruskin played throughout Wilde’s adult life, a role that extended to friendship with Wilde’s wife Constance.[2] As Unrau has detailed, in April 1888 Ruskin suggested that Constance present an award on his behalf at the Whitelands Training College. In a letter to the Reverend J. P. Faunthorpe, principal of the college, Ruskin wrote, “I think perhaps Mrs Oscar Wilde might like to do it Oscar has always been a most true friend to me, and she, more than I knew.”[3] Ruskin’s enduring friendship with Constance was built in part on mutual acquaintances from beyond Oscar’s circle: in February 1895, to give one example, Constance and Georgina Mount-Temple—confidante of Ruskin as well as Constance—hosted a party for Ruskin’s 76th birthday.[4]

Another instantiation of their friendship has escaped scholarly scrutiny. In the months before his letter to Faunthorpe, Constance apparently saw Ruskin in Sandgate, where he moved in August 1887 and lived through the following spring. The visit is documented by an inscription in Constance Wilde’s visitor’s book, now held in the Eccles Bequest at the British Library.[5] In her biography of Constance, Franny Moyle writes that Wilde’s wife, “ever the collector, and impressed by fame and success…made sure that she captured the signatures of some of her visitors” in the book.[6] It must be noted that in 1888, Constance and Oscar were still a united couple, well on the way to fame and socializing in rarefied literary and artistic circles. Indeed, signatories of the book comprise a who’s who of Oscar’s friends, colleagues, mentors, and idols, including Walter Pater, Robert Browning, George Meredith, James McNeill Whistler, and Charles Shannon and Charles Ricketts. Constance’s acquaintances, cultural luminaries, and passers-through also make appearances: George Grossmith, G. F. Watts, John Bright, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Mark Twain, Marie Corelli, and Vernon Lee all signed the book, among many others. Even Pablo de Sarasate penned the first few bars of his “Zigeunerweisen” above his signature.

Ruskin’s contribution is comfortably situated among such starry company. It appears a few pages after A. C. Swinburne’s contribution—a holograph copy of “Of such is the kingdom of heaven,” here titled “Children”—and a page featuring the signatures of William and Jane Morris. [7] Morris’s inscription seems wholly representative of his longstanding ethos: “The secret of happiness | To take pleasure in all the details of Life and not to live vicariously.”[8]

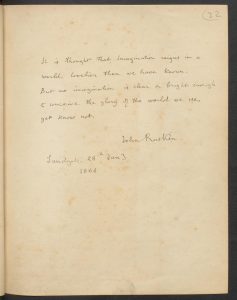

Written in a clear hand, and occupying its own page, Ruskin’s entry is in many ways similarly typical:

It is thought that Imagination reigns in a

world lovelier than we have known.

But no imagination is clear or bright enough

to conceive the glory of the world we see,

yet know not.

John Ruskin

Sandgate 28th Jany

1888[9]

Ruskin engages (albeit briefly) with the analyses of the imagination that extended throughout his long career.[10] An 1849 diary entry captures an early iteration of this theme. Considering the impact of ignorance and knowledge on the imagination—in particular, the impact of his geological knowledge on his ability to experience the sublimity of the Alps—he muses on ‘two things’ that determine the relationship: “firstly whether this knowledge, carried out or accompanied by further knowledge of God’s works (astronomy, &c.) would not, in the end, open still nobler fields to the imagination; and secondly, supposing it would not, how much the ignorant Imagination is really worth.”[11] Nearly fifty years later, writing in Constance’s book, Ruskin seems still to conclude that imagination alone is insufficient to know the “glory” of the world around us.

Ruskin’s line might cast into relief Oscar’s own relationship to the imagination, the complexity of which far exceeds the limits of this blogpost. Perhaps the most Ruskin-appropriate touchstone from this period is Wilde’s children’s story “The Remarkable Rocket” (1888), in which he skewers James McNeill Whistler—represented by an insufferably pompous firework rocket—whose famous altercation with Ruskin over his painting Nocturne in Black and Gold—the Falling Rocket was still a familiar memory. The self-deluded rocket insists, “Why, anybody can have common sense, provided they have no imagination. But I have imagination, for I never think of things as they really are; I always think of them as being quite different.”[12] For the rocket, complete disregard of fact (namely his arrogance and uselessness) leads to his ruin. Elsewhere in Wilde’s writing, his full-throated embrace of “beautiful, untrue things,” and his insistence that truth was not necessarily allied to fact, suggest that his notion of the imagination and its role in artistic vision was not the same as Ruskin’s.[13]

What Constance might have made of Ruskin’s entry is even less clear. Her limited published writing of this period—primarily children’s stories and a few articles for periodicals—does not address imagination; Moyle’s biography has precious little to say about Ruskin. There is an unfortunate tendency of among some of Oscar’s biographers to regard all moments of his life as leading inevitably to his trial and imprisonment, and in this vein, it might be tempting to read Ruskin’s inscription as an ominous foreshadow: Constance would likely have been unable, even with a clear and bright imagination, to conceive of the realities of the devastation awaiting her family just a few years later. But it was clearly the overlooked glories of one’s time that concerned Ruskin, not its potential miseries, and his inscription is better understood as an artefact of what was still a promising time in the Wildes’ lives.

Rebecca N. Mitchell is Reader of Victorian Literature and Culture and Director of the Nineteenth-Century Centre at the University of Birmingham. She has published widely on Oscar Wilde, Victorian realism, print culture, and fashion. Her recent books include Fashioning the Victorians: A Critical Sourcebook (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), Drawing on the Victorians: The Palimpsest of Victorian and Neo-Victorian Graphic Texts (co-edited with Anna Maria Jones, Ohio UP 2017) and Oscar Wilde’s Chatterton: Literary History, Romanticism, and the Art of Forgery (co-authored with Joseph Bristow, Yale UP 2015). She is currently co-editing Wilde’s Unpublished, Incomplete, and Miscellaneous Works for the Oxford English Text edition of the Complete Works of Oscar Wilde.

…………………………….

The author wishes to thank Merlin Holland and the British Library for permission to quote from and use the image from Constance Wilde’s autograph book, and to Lucy Evans and Hannah Francis for research assistance.

[1] e.g. John Unrau, “Ruskin and the Wildes: The Whitelands Connection,” Notes and Queries 29, no. 4 (1982): 316-317.

[2] Lot “98 Ruskin’s Modern Painters, vol. 2, and other books, Juvenal with plates, &c.” and Lot “102 Five vols. of Ruskin’s Works, blue calf, Ruskin’s Elements of Drawings, and other vols. Ruskin, etc.” Bullock Auction House, Catalogue of the Library of Valuable Books…Wednesday April 24th, 1895, reprinted in A. N. L. Munby, Sale Catalogues of Libraries of Eminent Persons, vol. 1, Poets and Men of Letter (London: Mansell, 1971), p. 381, 382.

[3] Quoted in Unrau, p. 316. Punctuation and italics as in Unrau. At the time of the article’s writing, the then-unpublished letter was held in the Wellesley College Library.

[4] Franny Moyle, Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs. Oscar Wilde (London: John Murray, 2011), p. 253. Later that month, Oscar received the accusatory calling card from the Marquess of Queensbury that ultimately led to Wilde’s arrest.

[5] Unrau mentions the autograph book (p. 317), citing Hesketh Pearson’s biography of Wilde (Life of Oscar Wilde [London: Metheun, 1952] p. 262). Ian Small also records its existence in Oscar Wilde Revalued: An Essay on New Materials & Methods of Research (ELH Press, 1993), p. 110.

[6] Moyle, Constance, p. 126-127.

[7] Swinburne’s poem first appeared in Tristram of Lyonesse and Other Poems (London: Chatto & Windus, 1882) as poem XXII of “A Dark Month”, p. 341. It appears as “Children” in the 1887 collection Select Poems (London: Chatto & Windus), p. 97. Though undated, context suggests the page was written in April 1887, when Wilde’s sons Cyril and Vyvyan would have been nearly two and six months old, respectively. Constance Wilde, Autograph book, Eccles Bequest. Vol. CXXXVII A; British Library Add MS 81755, p. 16. Used with permission.

[8] Jane offered lines from FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát: “My tomb shall be in a spot where the | north wind may scatter roses over it.” The entry is dated 23 March, 1888. C. Wilde, Autograph book, p. 23.

[9] C. Wilde, Autograph book, p. 22. As far as I know, the lines are published here for the first time.

[10] W. G. Collingwood, The Life of John Ruskin (London: Methuen, 1893), vol. II, p. 316. Neither Collingwood’s nor John Dixon Hunt’s biography of Ruskin mentions a visit from Constance at or around this time. Oscar Wilde’s published correspondence from the period shows him based in their family home on Tite Street in London, but letters from January 1888 are sparse and there certainly could have been time for travel. Constance’s biographers also do not detail a visit around this time, though there are records that the couple did respond to Ruskin’s invitations in March of the same year. Again, Unrau is the lonely source who recounts the episode.

[11] The Diaries of John Ruskin 1848-1873, Joan Evans and John Howard Whitehouse, eds., (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958) p. 416.

[12] Oscar Wilde, “The Remarkable Rocket,” in The Happy Prince and Other Tales (London: David Nutt, 1888), p. 100.

[13] Oscar Wilde, “The Decay of Lying” Nineteenth Century 25 (January 1889), p. 55-56.