‘India for ivory, Sardinia for silver, Attica for honey!‘ These were the well-known words of the Roman geographer, Solinus, which show the reputation that Sardinia’s silver had acquired in Classical Antiquity. Many centuries later, grants to exploit this precious resource were made to the Pisans at a time when they exerted power on the island in the 1100s. Clearly, Sardinia’s silver resources were still known and were prized, yet for hundreds of years we hear nothing about them. What had happened to the silver supply? This remains unexplained. What researchers think is that in the Byzantine period of the later 600s, a mint was in operation, probably in Cagliari. But after it closed down in the 740s, only a few coins of any type have been found. As such, it looks as if Sardinia had a long period in which its monetary economy was almost non-existent, and that it had returned to a cashless, service-based, barter system of payments. If so, then the island’s economy was very different to those around it because in the Iberian Peninsula, North Africa, Sicily and south Italy minted coins were used to pay for goods, services, materials, officials, soldiers and so on. While these regions and their merchants thrived in an interlinked market, Sardinia seems to have plunged into an economic ‘dark age’. How and why could this happen if Sardinia had silver? Why did the medieval Sardinian rulers not make use of their silver resources?

Most silver is obtained by smelting and processing lead ore from which it can be separated. Scientific testing of metals, or archaeometallurgy, can determine where the silver came from because the isotopes or chemical elements in lead and silver can be traced – and the chemical signature for Sardinian lead ore is distinctive. This means that if we analyse, say, a silver coin, we can tell if it came from Sardinia or not. Now, if Sardinia was exporting silver bullion overseas either for trade or as tribute payments as some scholars believe, then we can use these tests to find out.

For our first tests, we decided to use silver coins from al-Andalus (modern Spain) and especially from Ifrīqiya (Tunisia). The reason for this was both practical and historical. Medieval coins are so rare in Sardinia that it is difficult to get permission to test them. Second, is that Ifrīqiya and Sardinia had been part of the same political region of ‘Africa’ in the Byzantine period (535–698 CE). Towards the end of the 600s, the Arab-Muslim conquest of North Africa split ‘Africa’ from Sardinia. As a result, Sardinia remained Byzantine, but Africa (‘Ifrīqiya’ in Arabic) came under Muslim control. During the early 700s and early 800s, chroniclers recorded raids on Sardinia from Muslim Ifrīqiya and Spain in which booty and plunder was taken. In some cases, tribute payments were also said to have been made. Had these Muslim regimes been making their coins from Sardinian silver? We targeted precisely these periods by acquiring 28 silver coins (dirhams) minted from the Arab-Muslim Umayyad and Aghlabid dynasties during and after the period of the recorded raids.

The analysis took place in the Institute for Geosciences at the University of Aarhus, Denmarkwhere the project co-investigator and archaeometallurgy expert, Dr Tom Birch, works.

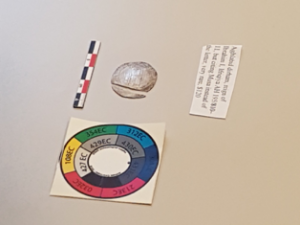

First, the coins were photographed and catalogued.

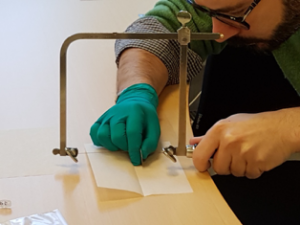

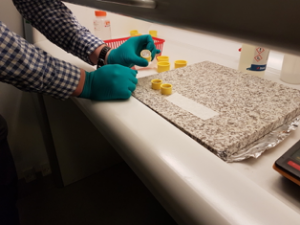

Dr Marco Muresu, a specialist in Sardinian numismatics and post-doc on the project cuts away a section of each coin.

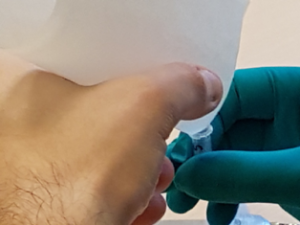

Silver dust from the cutting is gathered.

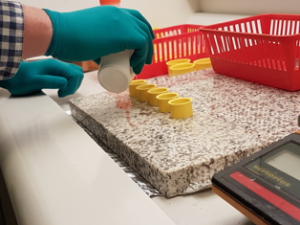

Epoxy resin is prepared by lab manager Dr Rasmus Andreasen in plastic rings to set the cut samples

Catalogue references are added to the epoxy resin so that the samples cannot get mixed up.

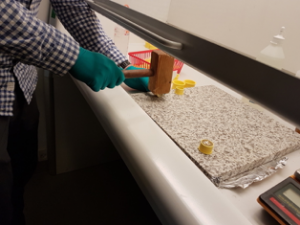

After the epoxy has set overnight, the resin can be carefully ground and polished. During the analysis, when a laser is pointed at the cut samples, it will hit a perfectly smooth surface.

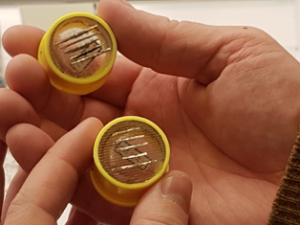

Overnight, the coins are left to set in the resin. Next day, the samples are released from their plastic holders using a wooden hammer.

One of them already looks different from the others and has a copper colour to it. We will need to find out why.

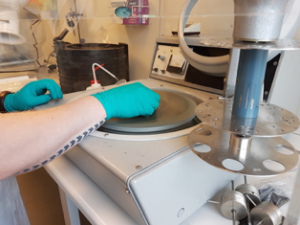

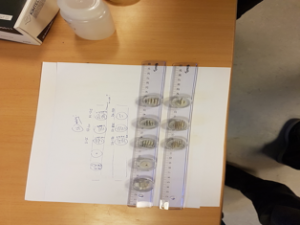

The samples are fixed to a plastic ruler and we ensure that each of them is perfectly level for the next stage – micro-XRF analysis.

The blocks also include a sample of silver of known value to make sure that the results are accurate.

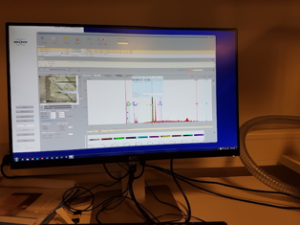

The first results showing presence of different chemical elements begin to appear on the screen.