From around 1750 to 1850, the Industrial Revolution changed life in Britain. It was a very important period in British history.

During this time, factories were built, to produce goods such as textiles, iron, and chemicals on a large scale. The steam-engine was invented, which could do more work than men or animals, and canals and railways were built, to transport goods and materials for manufacturing.

The Industrial Revolution created a huge demand for coal, to power new machines such as the steam-engine. In 1750, Britain was producing 5.2 million tons of coal per year. By 1850, it was producing 62.5 million tons per year – more than ten times greater than in 1750.

Here is a picture of a coal miner from 1814, when the Industrial Revolution was gathering pace. In the background, there is a steam-powered locomotive, used to transport the coal in waggons along rails, and steam-powered mine machinery, designed to help the miners bring the coal to the surface and to pump out water from the mine. Animals, such as the horse in the background, were still being put to work, but the new machines were much more powerful.

As the demand for coal increased, miners were forced to go deeper underground to find new coal. Deep tunnels were dug underground, where the conditions were dark, hot, and cramped.

Here is a picture of a miner working underground. He is hewing (cutting) coal with a pick axe. Because it is dark, he is working by candlelight, and because it is hot, he is not wearing many clothes. As the tunnel is so cramped, he has to work on his knees.

Coal mining was a very dangerous job. The tunnels, which were sometimes propped up with wood, sometimes collapsed. The miners sometimes came into contact with dangerous gases that existed naturally underground.

The most dangerous gas in coal mines was called fire-damp. It was mainly composed of methane, like the natural gas that we use for cooking and heating today. If a miner came into contact with fire-damp underground, the flame of his candle would sometimes cause the gas to explode. Fire-damp caused many explosions in coal mines, and these explosions caused many deaths of miners.

One of the worst explosions took place in Felling, near Gateshead in the north-east of England, in 1812.

This explosion, which happened on 25 May 1812, caused the deaths of 92 miners. Here is a list of all of the men and boys who were killed:

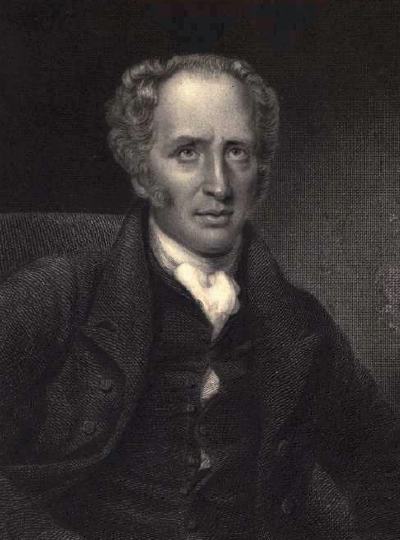

The Reverend John Hodgson (1779-1845) was the rector (priest) of the parish of Jarrow-with-Heworth, where Felling Colliery (coal mine) was located. He wrote an account of the Felling Colliery Disaster, containing the list above, which was published in 1813.

Here is Hodgson’s description of a fire-damp explosion:

‘The whole mine is instantly illuminated with the most brilliant lightning – the [explosion] drives before it a roaring whirlwind of flaming air, which tears up every thing in its progress, scorching some of the miners to a cinder, burying others under enormous heaps of ruins shaken from the roof, and, thundering to the shafts, wastes its volcanic fury in a discharge of thick clouds of coal dust, stones, timber, and not unfrequently limbs of men and horses’.

Here is Hodgson’s description of the explosion at Felling on 25 May 1812. Felling Colliery had two deep shafts, called John Pit and William Pit:

‘About half past eleven o’clock on the morning of the 25th May, 1812, the neighbouring villages were alarmed by a tremendous explosion in this colliery. The subterraneous fire broke forth with two heavy discharges from the John Pit, which were, almost instantaneously, followed by one from the William Pit. A slight trembling, as from an earthquake, was felt for half a mile around the workings; and the noise of the explosion, though dull, was heard to three or four miles distance’.

‘In the village of Heworth, [the dust from the explosion] caused a darkness like that of early twilight, and covered the roads so thickly, that the footsteps of passengers were strongly imprinted in it’.

‘As soon as the explosion was heard, the wives and children of the workmen ran to the working-pit. Wildness and terror were pictured in every [face]. The crowd from all sides soon collected to the number of several hundreds, some crying out for a husband, others for a parent or a son, and all deeply affected with [a mixture] of horror, anxiety, and grief’.

‘One hundred and twenty-one [people] were in the mine when [the explosion] happened’.

It was not safe to re-enter the mine until more than a month later. Here is Hodgson’s description of that day, 8 July 1812:

‘The morning of Wednesday the eighth of July, being appointed for entering the workings, the distress of the neighbourhood was again renewed at an early hour. A great concourse of people collected […] to witness the commencement of an undertaking full of sadness and danger[.] [Most] came with broken hearts, and streaming eyes, in expectation of seeing a father, a husband, or son “brought up out of the horrible pit!”’.

‘From the eighth of July to the nineteenth of September, the heart-rending scene of mothers and widows examining the […] bodies of their sons and husbands, for marks by which to identify them, was almost daily renewed[.] […] Their clothes, tobacco-boxes, shoes, and the like, were […] the only indexes by which they could be recognised’.

As the mine was explored, more casualties of the explosion were discovered. Here is Hodgson’s description of 15 July 1812:

‘Twenty-one bodies […] lay in ghastly confusion: some like mummies, scorched as dry as if they had been baked. One wanted its head, another an arm. The scene was truly frightful. The power of the fire was visible upon them all’.

The mine did not re-open until 19 September 1812 – almost four months after the explosion. In his description, Hodgson noted: ‘The body of number ninety-two has never yet been found’.

After the Felling Colliery Disaster, a new society was founded in 1813: the Society for the Prevention of Accidents in Coal Mines.

A monument to the 92 men and boys who were killed in the disaster still stands today, in the churchyard of Hodgson’s old church in Heworth. In 2012, two-hundred years after the disaster, a blue plaque was put up next to the monument to commemorate the miners who were killed.

Click here to go to the next section