Provocations

Sarah Dyer

When we advocate for the design of learning activities and programmes in university education, what do we really mean? At its most fundamental what is good design of education? How do we judge whether something is designed well? And what skills and mindsets does it require?

When I started working in universities the general consensus seemed to be that course units/modules and programmes were a kind of organic or magical thing that emerged or evolved. Planning them seemed to be a case of listing topics against weeks and writing exam questions with the right level of challenge. Advocating that learning activities need to be designed was radical and has been really successful in improving the quality of much university education.

I’m interested in zooming out and thinking about what those us of who advocate for design in education are asking for.

For myself, when I taught on a PCAP I wanted to support academics to start with what they were trying to achieve (designing backwards from sound Intended Learning Outcome), think about constructive alignment of the elements of the unit/module, and create a clear narrative and ongoing feedback dialogue. When I look back though my HEA fellowship applications, the evidence I present of this activity centres around identifying what I am trying to achieve, the things I do to support that outcome, and evidence of its success and areas for improvement.

I enjoy creating an architecture for learning and also have the sense that elegance matters in education design: a rhythm to a module or a repeated motif which scaffolds students learning.

Are there key things you would want to include? What does it take to design university education well?

Tony Morgan

This provocation considers the question what has design thinking got to do with higher education? Or to misquote Tina Turner: “What’s design thinking got to do with it? What’s empathy but a second-hand emotion?”

Before a late career change, I worked for a large technology company which was seeking to become more customer focused. Working in an innovation role, I was delighted when the organisation placed more emphasis on “design thinking” or “human-centred design”. Nowadays, I teach students to understand and apply many of the design thinking and related techniques I used when working in the company and with other organisations.

In academia, many people are unfamiliar with (and sometimes suspicious and sceptical of) terms such as “design thinking” or “human-centred design”. Although this may be true, there’s a more positive side too. Many of my colleagues and peers apply similar concepts and approaches every day, for example when creating or improving modules, without even thinking about it.

What do I mean by this? Well, they might not be using design thinking techniques such as personas, empathy maps and needs statements, but they emphasise with their students. When they’re developing new programmes and modules, they define student needs and learning outcomes and design teaching and learning in ways which students can best achieve these. For example, they understand that not all students learn in the same way and seek to include a variety of approaches and resources to address different student needs.

(Design Thinking Activities, Illustrator: Dan Trowsdale)

For existing modules, they assess student feedback and ideate (although most of us though probably prefer a phrase such as “generate improvement ideas”). They implement (or what some design thinkers might call prototype) improvements and test them during the next run of the module.

And then they iterate. They read the room. They review student feedback, surveys and evaluations. What worked? What didn’t? What new ideas and approaches can be learned from colleagues’ practice, journals or conferences? What can we do differently to create a better student experience next time?

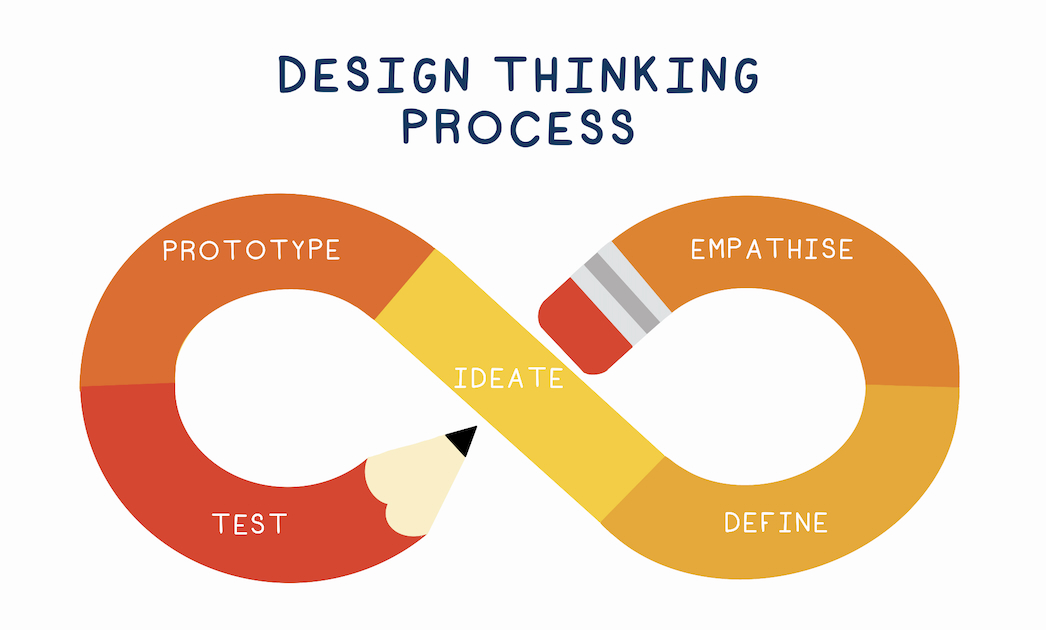

In a way, they’re following the classic “design thinking” five-phase loop.

- Empathising with students.

- Defining their needs.

- Ideating what we can do to make a positive difference.

- Implementing (or prototyping) improvements to meet student needs.

- Testing them out, gaining feedback and going back through the loop for the next run of the module.

(Design Thinking Iterative Loop, Illustrators: Shriya Pankhania / Madeleine Knight)

So what? If academic colleagues are already taking a design thinking-based approach, why should we care? Personally, I draw three conclusions from this discussion.

Firstly, some colleagues aren’t using the above approach and don’t take enough note of the needs of students and other stakeholders. If so, perhaps they need to be encouraged and supported to do this, but that’s beyond the scope of what we’re discussing here.

Secondly, for the many colleagues who have bought into the above approach, there are tools and techniques that many of them are unaware of which can really help. Design thinking and related approaches provide some great and very practical ways to generate empathy, define problems, generate, review and prioritise ideas, implement / prototype ideas and gain feedback so we can make the next set of improvements. I know this because the teaching team I work with use them, and we see the benefits for our students.

As a start, at the University of Leeds, we’ve created a new bottom-up Design Thinking Community to share ideas and good practice. Looking more widely, it would be great to create a kitbag for educators to make it much easier for them to use design thinking techniques.

Thirdly, and to support the previous point, work needs to be done to make it easier for educators to understand, adopt and gain the benefits of using design thinking and human-centred design. How can we do this? One approach is to better align the language and techniques used in design thinking with higher education frameworks.

I’m working with a great team of people at the University of Manchester, Lancaster University and the University of Leeds to do just this. We’re beginning with taking a look at how we can align Design Thinking to support the UK AdvanceHE Professional Skills Framework (PSF), but we don’t have all the answers yet.

Iria Lopez

I ask myself this question.

The answer I’ve received normally is students, and they are right, but I also feel it’s a bit more complex.

Everyone I speak to say that they listen to their students, what sometimes they mean is that they have conducted surveys to capture their feedback, or have referred them to their tutors.

Many academics are conscious of the importance of building a relationships directly with students do get to know their names, their struggles and adjust their approach accordingly, or refer them to other support if needed.

We need to be aware of this context when we ask academics to develop empathy for students. Without that awareness, we won’t be able to influence change in HE.

From my perspective, there is a need to create spaces where we bring academics and students in dialogue where they directly hear each other stories. Stories are powerful, and those stories is what could also help academics review their list of priorities. It is less about adding yet another ‘to-do’ to the academic’s list, but to re-prioritise and align the ask students have for an engaging and exciting student experience to academics career progression needs in HE. What barriers academics have to develop empathy for students? That’s also a question I ask myself.

I have learned, since I landed in Higher Education two years ago, with a background in service design / people-centred-design, that HE is a student’s learning journey that requires the understanding of a wider system. I have learned that improving a curriculum requires understanding the lived experiences of multiple perspectives, not only students and academics, but also placement supervisors, community, internal processes staff members and other key players.

What people-centred-design mostly can bring in this complex context is a space to facilitate conversations under structured and facilitated activities that break down the complexity in a way that is addressable and manageable. HE urgently need design facilitators able to support co-creation between stakeholders (including and at the centre of it, students) in an authentic way.

For those less familiarised with people-centred-design I would like to share with you a brief example of what I mean.

The first stage in a design process, is to develop empathy:

For example, we could interview students and learn through that conversation that they are struggling to know how to articulate the skills they are gaining in their module. Or, they might not be aware what specific skills they are developing.

We could also conduct interviews with employers, and through those conversations learn that they feel frustrated with students difficulties to work as in team, challenges with inter-personal skills, or presentations skills.

If this would be the end of the story, then we can frame the challenge (“definition stage “in the design process) as: how might we develop and surface team-work skills?

However, the challenge we face is more complex.

When we explore the perspective of academics, in some cases, they don’t have the time to integrate the skills with all the competing priorities that they need to fit in. It could be that they, themselves, don’t have the headspace to go deeper in understanding how to integrate them, it could be that module leads are not having visibility of what other module leads are doing and they don’t know how their programmes could be simplified while integrating those skills to be developed.

Then, we need to question whether the actual challenge we need to address is how to develop and surface students skills? Or whether we need to develop first empathy for the context academics work in.

With this example, what I am trying to showcase is that we need to see the scenario from multiple angles. Unless we fully understand the motivations and barriers that everyone in the system has, we won’t be able to design student-centred learning journeys.

People centred design allows us to have empathy for each perspective, identify what scenarios are we designing towards, what are the barriers, so that we can frame the problem focusing on ‘why’ is this happening, instead of the symptoms of the problem.

The first two stages of a design process (empathy – framing of the problem) are highly overlooked by most organisations I have ever worked on, this is not specific to HE. Specially in technological sectors there is a strong tendency to assume what context they are designing for, and immediately launch technical solutions.

People-centred-design normally is defined with five steps: empathy – frame – ideate – prototype-test and iterate, but I have dedicated most of this blog to the first two steps to highlight the importance of understanding who we are designing for.

Having said that, trying out initiatives and seeing what sticks, which is a quick way of talking about the remaining stages (“ideation-prototyping-testing-iterating) is also a way to learn about what people need. However, if we directly jump into stage 3 “ideate” without clearly understanding the problem we are designing for, (differentiating between symptom and root causes) we might be focusing on the wrong problem.