With Painting: Spectatorship, Temporality and Modes of Address

“Remember that there is only one important time and it is Now. The present moment is the only time over which we have dominion.”

(Tolstoy L., The Three Questions, 1885).

Tolstoy, in his short parable, recounts the tale of a king in pursuit of answers to fundamental questions of ethics. When is the right time for every action? Who are the right people to listen to? What is the most important thing to do? Disappointed by responses from eminent, educated men, the King duly ventures to see a wise old hermit living in a hut in the shaded woods, to put these questions to him. Witnessing the silent and frail hermit digging a ditch, the King joins in. Later, the king is about to leave, sensing that he will not come upon the answers he seeks, when suddenly he spots a wounded man running towards him. He tends to the man’s wounds and nurses him through the night. In the morning, the man begs for forgiveness, and explains that he was an enemy of the king. In fact, he had intended kill him, prior to being wounded by the King’s guard. The King, moved by the man’s confession, forgives him and orders his attendants to nurse him back to full health. The hermit explains to the King that had he not stopped to help him dig the ditch the assassin would surely have attacked him, so the most important time was the time that the King spent digging, and, at that time, the hermit was the most important man. Similarly, attending to the wounded man afforded an opportunity for reconciliation. To be preoccupied with what has been, the King realises, is to burden oneself with guilt. Likewise, to anticipate the future is to endure the pain of anxiety. The most significant relationship is the relationship to what it is that one now has. And so, one must seek to live in the moment, and, in that moment, live to relinquish seeking.

The power of Tolstoy’s tale comes from the urgent reminder that in paying attention to current preoccupations we permit ourselves to become liberated from stress and doubt; we proceed to act, and to attend to, and to cement connections with, and to draw strength from. In an unusual sense, our time, then, becomes stilled, and, to Tolstoy, this affords fulfilment and happiness. Of course, Tolstoy, as is consistent with his ethical stance, for the most part directs this form of engagement to other human beings; relationships, friendships, love, and the communion of Man. However, I hope, here, to borrow something from Tolstoy’s ethics for what could be considered almost aesthetic ends, and to offer up an account of temporal engagement in respect of painting. In so doing, I would like to consider the notoriously thorny and sometimes overlooked issue of spectatorship. How is a painting to be approached? What might it mean to speak of modes of engagement? How might knowledge of past and future – or indeed the language of past and future – operate in the interpretive moment of address?

By thorny, I refer to the legacy of contestations surrounding concerns to do with the encounter – within modernist art historical discourses of the 1960s – that appear at their most pronounced in the art criticism of Michael Fried, but also in the Minimalist moment per se. By sometimes overlooked, I mean to imply the downplaying of such concerns – perhaps the result of battle fatigue – within contemporary discourses in favour of far more pluralistic, issues-based understandings of the situatedness of painted objects, that, more often than not, begin with the more comfortable clarities of purpose, intention and use. I am not now intending to comment on matters of quality, nor to revisit Fried’s position vis-a-vis the instantaneity of modernist paintings. By invoking aesthetics, I mean only to locate this analysis within a lineage of thought; to recognise an historiographic unfolding across an extended period of time. This might appear, on the surface of it – no pun intended – to be a rather strange move. Afterall, why invoke painting’s past in a short essay to do with painting’s now?

I do hope that the answer to this becomes more apparent as this exposition unfolds, but for now I would like only to suggest that designations of temporal facticity require a form of bracketing. By bracketing, I mean literally the establishment of separations – the keeping of one thing from another so as to name it and award it distinguishing properties – and so the tripartite structure of past-present-future becomes usable in the course of framing not only the present in respect of past and future but also the past in respect of the present and future, and the future in respect of the present and past, too. The key point to be made, however, is to suggest that, in bringing forth the now as the primary position from which all other related distinctions and terminologies are to become knowable (and to not know it from afar, and only in relation to the designations that sit to each side of now), the knower has already, inadvertently, worked to attain a privileged interiority in respect of the use of these terms, from which to reclaim both past and future in the pursuit of the framing of the particularities of the present.

Let me turn now to painting. When a painting (by painting, I refer to that which is taken to be a painting in the moment of contact) is approached – to know it – it is necessarily of the past, in the sense that one presumes that its existence has preceded the particularity of the encounter to hand. On leaving the painting (to move on to something else), one likely assumes, also, the painting’s continued occupation of space and time, and so, in this sense, if in no other, the painting can be said to be of the future too. Objections could of course be raised to this, to postulate either the birth of the painting within the period of the act of looking, or else its subsequent dissolution post-looking. Nonetheless, the point remains, that on encountering a work of painting, irrespective of the context in which the painting is to be found or presented, the spectator narrows his experiential focus to the time in which the painting is to be considered, whist holding, unconsciously perhaps, onto the notion of the painting’s extended reach into the past and the future. My time with this painting means, in effect, an opportunity to inform me of something now.

And yet, when the makeup of this now is considered, it turns out that whatever is garnered is usable in the future too. This wonderful Wordsworthian thought – the expression of which Wordsworth returned to again and again in the course of his poetic life, most notably in Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood (1807), and The Prelude (1850), appeared first in Lines Written above Tintern Abbey (1798). The recognition that the value of his experiences of nature were two-fold – supplying food for both the present and the future – served to revolutionise conceptions of temporality and at the same time centre experience and the processes of memory. Moreover, the value of sharing times with others offered more than one party access to the fruits of these processes. The imaginative faculty became, to Wordsworth, and to the Romantics that followed in his wake, something of a magical sanctuary, and, as such, a precious thing to be nurtured, protected, and even shaped. This shaping became Wordsworth’s lifelong project. Its extensions, however, not only pushed the boundaries of poetic possibility, which in turn provided a framework for artistic meaning that persists to this day, but also marked a truly momentous shift in human consciousness.

To dwell in/on poetry meant to take an experience of the present and to situate it within a future temporal space. This involves multiple projections, for taking the present to the future in order to look back at the now also means being able to situate the present as past; as something that has already taken place. The usability of time in art, and indeed in life, permitted all manner of travel; of application and re-application of events, intentions and thoughts, in the spirit of a deeper level of enrichment too easily occluded by a dull rootedness to the now as now only. A conception of the present as manifold in nature served, then, to provide the receptive spectator of phenomena – frequently the natural world – with a toolkit with which to work away to engorge life’s experiential and aesthetic possibilities, so as to have them push beyond the day-to-day. In this, however, there was no intention to undermine quotidian comings and goings, for such a move would amount to little more than redaction. Wordsworth’s call was to find meaning, then value, in the prosaic and the passing, and to maintain this value – whilst accepting its propensity to alter – for use at other times. To draw from the past meant to take sustenance from it, having earlier laid the groundwork.

In respect of painting, and so as to offer an account of spectatorship that seeks to understand the composition of a loaded present, it is necessary to filter thoughts into discrete categories, and also to reflect on that which remains essential in the coming together of object and subject: of painting and spectator. First, seeing a painting involves cognition. The seeing eye is in fact a thinking eye, irrespective of the speed at which sense data is unpacked and made sense of. There is no seeing alone, or, more accurately, if there is, then there is certainly no talking about it. To see, then, is only to have seen, and most likely to have remembered prior acts of seeing. Moreover, to return to the bracketing I mentioned earlier, there are likely to be limits to the contents of what is able to be seen and thought – or seen-thought – within each encounter with a painting; the result of a confluence between the painting’s particularities (formal, iconographic and material) and the spectator’s prior experiences. It requires stored knowledge of the world – able to be accessed, perhaps consciously and/or otherwise – and of pictures of the world, to see a landscape painting as a landscape painting.

These processes of seeing-thinking, whatever the mechanisms behind their operability, are experienced, as Edmund Husserl famously noted, in Logical Investigations (1900), as experiences of. In respect of the matter to hand, experiences of will relate only to painting. Of what might such experiences be constituted? Within debates as to the meaning of painting sit a number of influential schools of thought. Within the modernist period, formalism, for the most part, attained a primacy over the more contextual frameworks of understanding. To Roger Fry, the experience of a painting’s form required a bracketing out of what might otherwise be referred to as its subject matter (to some, its content). To Erwin Panofsky, on the other hand, the experience of a painting became enriched enormously when one permitted oneself to delve beneath the formal particularities of works in search of iconographic layers of meaning. In this way, importantly, possibilities could be unpacked incrementally, in time. The implications of such divergent approaches in respect of time were underscored later by Clement Greenberg, whose disavowal of literariness in painting helped to establish instantaneity as a prerequisite for aesthetic appreciation. Excavations of the Panofsky kind, therefore, to Greenberg, added interest only.

And yet, what is of interest most, perhaps, is that which too easily gets lost in discussions of the nature and potential of opticality (what Marcel Duchamp termed the retinal) versus conceptualism and/or contextualism: that is, the place occupied by time. Seeing, confronting, taking in, spending time with, beholding, being in proximity to, etc., denote a type of relationship, in this case to the painting. Processes of engaging with form, or else of unpacking contextual possibilities, or even some combination of both, take place within the context of this coming together. Irrespective of the length of this – let me choose encounter from the prior list, though the others would equally suffice – something happens, and it is a something that in experiential terms has a temporal extension. Encounter, then, has duration, and duration has the particularity of orientation, in the sense that one’s experience of duration – here at least – is oriented-towards (the painting), and so is to be designated an experience of.

What, then, are we to make of this space or clearing in which meaning happens? What, also, has this to do with Tolstoy’s understanding of time? And what of the nature of the now? To move this on, I need to say something about the mechanism of acquiring and relinquishing information in the moment of encounter. If, during a particular encounter, something more is made of a painting, could it be said with accuracy that this more has arrived in place of the less that preceded it, or would it be more appropriate to say that the less that preceded it has been amended by/as the more that this less became, and now takes another form, i.e., the more? The former possibility implies that new information simply replaces old information, which seemingly vanishes from view entirely, as the new asserts itself suddenly (from nowhere), and the latter possibility is that information transforms into other information, which in turn serves, in dialectical fashion, to preserve something of that which preceded it. If the latter seems more persuasive, then acquisitions of meaning are informed by the conditions present, and by conditions I refer to both the stimuli of the painting and also to that which constitutes the spectator’s prior experience, which would include his knowledge base. To use a painterly analogy, this would be to ascribe to one’s experience a medium or vehicle to carry memories on.

By memories, I mean to imply whatever happens to be usable in the course of framing an experience of painting. The notion of a space or clearing, wherein that which is meaningful becomes operable as (painterly) meaning derives from the Heideggerian idea – Lictung – and is rooted in the temporal conditions of Being-in-the-world. It is useful here only in so far as it legitimises speculation, if legitimisation is needed, as to the contents of durational experience, which might then be taken to be a thing. Having opened up, the activities therein, through the mechanism of disclosure and concealment, are able to be spoken of and made sense of. This mechanism, to Heidegger, is reciprocal, permitting visibility as it sanctions neglect. And when a painting is spoken of and made sense of, the form that this speaking takes takes the form of descriptions of, and reactions to, one’s impressions of this content.

Tolstoy’s now denotes a period of stilled time, that from the outside manifests itself as simple duration – it happens over a period of another’s time. Yet from within, as a result of preoccupation and acts of engagement, this passing is relinquished. More accurately, it could be said that the Tolstoyan now becomes unshackled from cause and effect, and it is this experiential unshackling that permits the freedoms discussed earlier; namely, the shedding of guilt (over the events of the past) and anxiety (as to possibilities of the future). To map this onto an experience of a painting requires first that the experience of the now become unburdened by past regret and future trepidation. It would be a mistake, however, to equate past regret with knowledge, or future trepidation with anticipation. Regret and trepidation amount to uses of knowledge and anticipation. The designation of the now as that to which all else is subject not only empowers one with the ability to act – here, to act to interpret – but ensures a clarity of possibility, providing limits. For Tolstoy, the now denotes a working out from present engagements, and such preoccupation can be seen to draw its neighbours in in the course of framing itself in distinction from them. Both past and future are able to be understood not in opposition to the present but as present, in the moment of the present.

The now of old, if I might be permitted to put it this way, is a now to be understood only in contrast to both past and future (not with), and this serves, in turn, to squeeze the present out of the picture. This old now rushes forth, intent on becoming free of that which has been, in search of that which has yet to come, and in the process surrenders itself. The new now, however – the now of which Tolstoy speaks – is something else. The sense supplied by Tolstoy is akin to an enmeshing within the fabric of time. To know this now is to have it become operable – to know it as the most important time, the time over which we have dominion. It is to render immanent the grain of things through a direct engagement with that which has offered itself up to be known. This now is, in effect, a hermeneutic clearing; a chronological hiatus; a jamming of temporal traffic; a mode of address. And so, to be with a painting, then, is to become receptive to a painting’s fullest present extensions, in the knowledge that these extensions derive from a sensed significance of what has been and what is to come.

Dr Tom Palin

Here and There, oil on oak, split panel, 2023

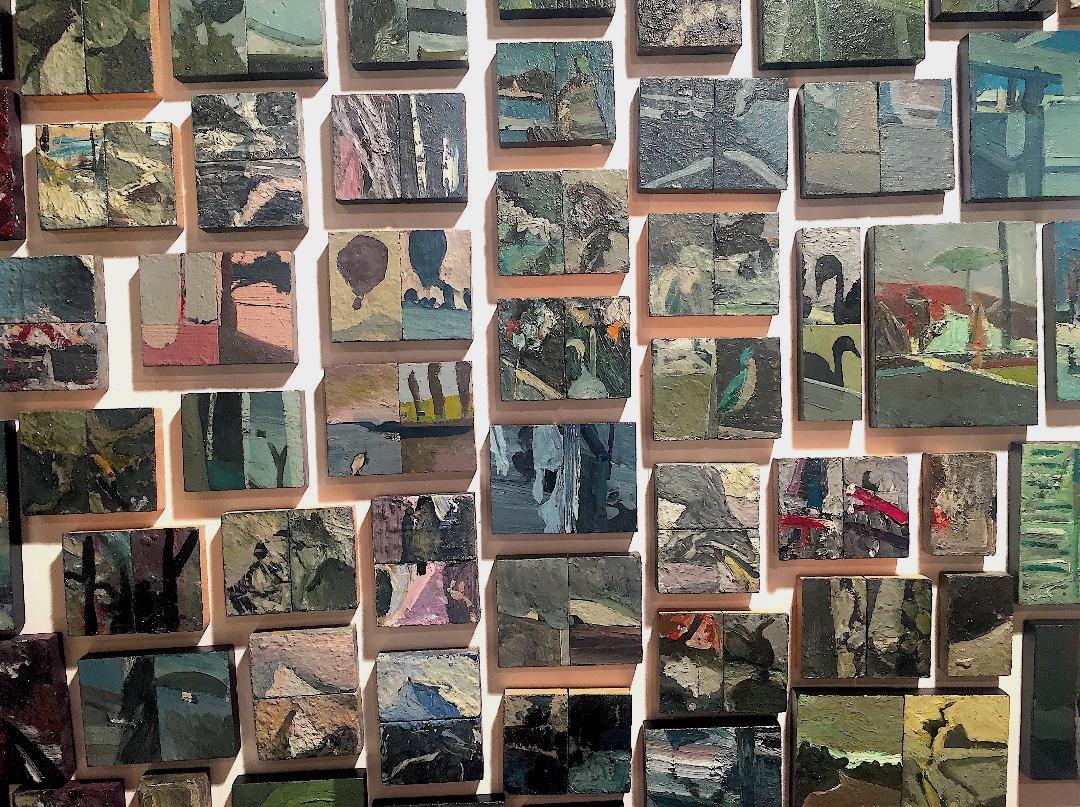

Here and There, oil on oak, split panel, 2023  Oil on wood, studio floor, 2012-2020

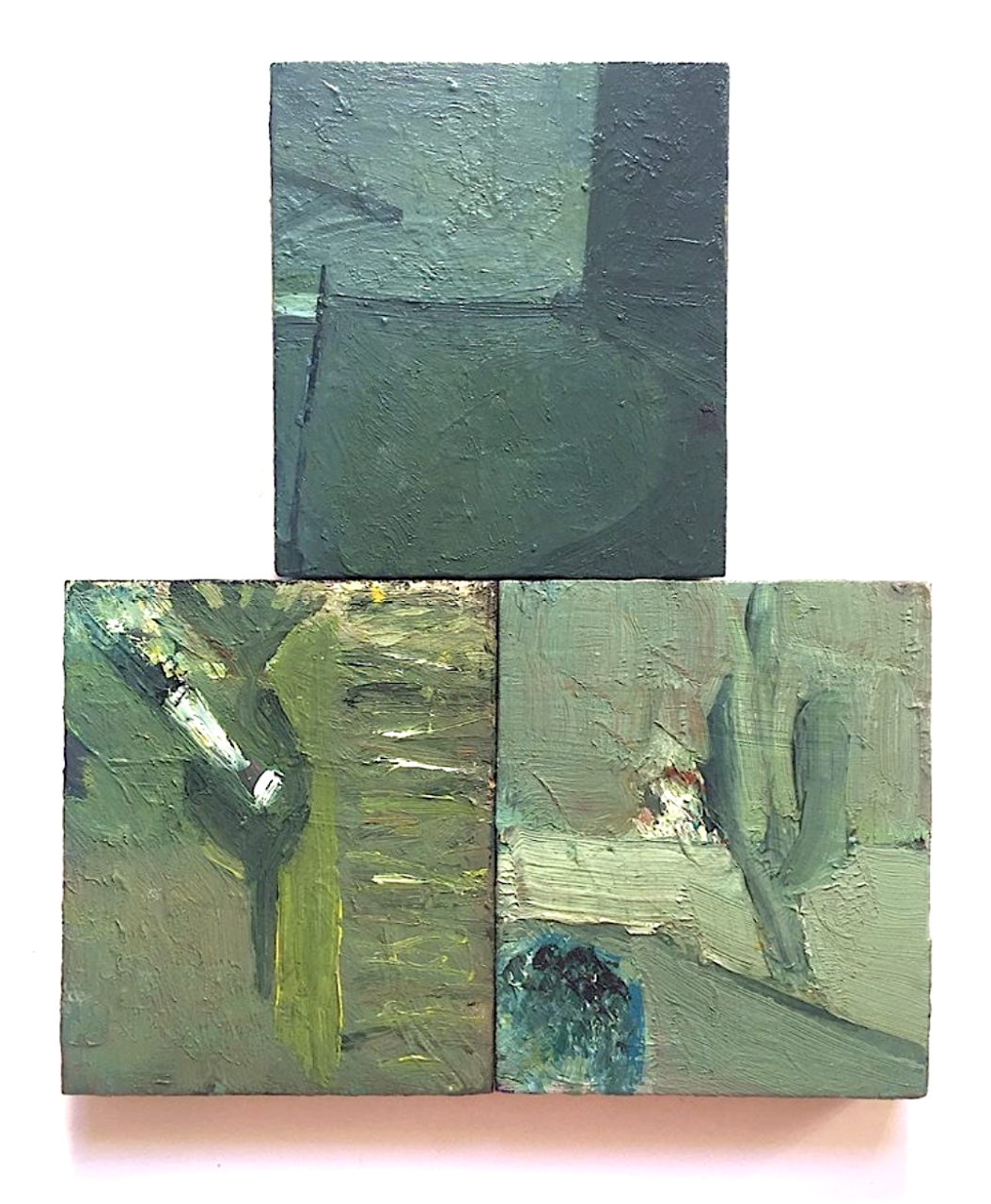

Oil on wood, studio floor, 2012-2020  thumbnail_Trinity 2, oil on three wooden panels, 2022-19

thumbnail_Trinity 2, oil on three wooden panels, 2022-19