Drawing as Erratic

It’s raining. Again. Outside, the air seems lulled by the steady monotony of Scottish winter rain. It’s not the first day. The loch has filled. The burn behind the house is running high and fast, the overflow channel nearby a second torrent. I watch nervously as it edges higher.

This outlet was formed over 11000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age as the glacier that filled the valley began to warm. As the pressure of meltwater built up behind the moraine, it found its way out at the lowest point, bursting through the moraine, forging a channel through the band of rock upon which my house now stands. As further melt ensued, more ice turned to water, flooding the hollow scoured by the icesheet, then draining away until inflow and outflow stabilized into the calm expanse of water in which I now love to swim. It’s curious to think of this placid beauty spot as a site of the geologic trauma that birthed the Holocene. Other traces are visible: rocks bearing grooves gouged out as if by giant talons; boulders strewn around the fields above the loch have been left high and dry as the icy flow that once carried them receded. Bedrock ground down under the weight of moving ice has become sediment forming a ‘beach’ at the water’s edge and settling as a silky silty blanket in the depths. The finest of this particulate, glacial flour, is occasionally whipped up into the water on turbulent days, carried with the flow and as the water level subsides. Then after days of evaporating sunshine, these sediments trace the water’s edge, dusting the banks above the water line with a dull ochre shimmer delineating the water’s passage. A veritable drawing is it not? A ghost of a flood, and of the ice that went before.

These traces, these erratics,[1] lie a reminder that glaciers are not inert, dead things somewhere else. They have touched and left their mark the skin of the land we now inhabit and cultivate. Neither are glaciers unified stable geologic features, but porous shifting entities of entanglement, sweeping up and transforming matter– animal, vegetable, mineral – enveloping it, ingesting it, excreting it. They transport one part of a landscape to another, forming new terrains along the way. It is perhaps not surprising that glaciers have been both feared as monsters and venerated as gods.

This is glacier as force, a geological agent, an entanglement and an archive of the past. It is enchanting to think of those Antarctic ice cores with their pockets of air carrying the atmosphere of the past into the present. Ice that last fell as snow as the first humans drew breath. Records of events past, long before our time. In more populous regions of the planet, ice also carries more visible traces of human history into the present in the form of glacial archaeology. This is the study of artefacts buried not in earth, but ice. Unlike terrestrial archeology, ice bound finds do not follow the same stratigraphic order with newer finds on top– a slow moving churn of a glacier is no place for things to stand still. Artefacts from 50, 500 or 5000 years ago might emerge in the same year. Artefacts can emerge unexpectedly and are often discovered by non-specialists – hikers and climbers.[2]2 In the European Alps there are currently public awareness campaigns to alert mountain goers to the potential existence of emerging archaeology in an attempt to identify finds before it is too late.[3] Archaeology from ice is particularly valuable. The arid and subzero conditions preserve fugitive materials such hair, textile, leather that would readily decay in the moist conditions of terrestrial burial. Some of the earliest practices of weaving in alpine Europe were revealed by glacial archeology. However, while these rare and valuable artefacts provide important knowledge about the past, this insight comes at the cost of environmental change and threatened futures. What’s more, these precious finds are themselves vulnerable and will rapidly deteriorate and disappear, once awakened from their slumber by the thaw of global heating.

This presents a compelling conceptual framework, focusing not on what is lost (the ice), but the things that emerge as a result of this loss, an inversion of negative and positive. It reminds us that loss is not a simple, singular thing. Instead, as the ice melts we are compelled to ask, what is lost? For whom is it lost? What is revealed in its place? And what does ‘lost’ mean anyway?

The Emergency! exhibition aims to explore the precarity of this context asking how might the material intelligence of drawing – with its use of marking and erasure, presence and absence – negotiate these tensions and find new ways of articulating the nuances of loss and change engendered by the global climate emergency?

***

I first set eyes on an item of glacial archaeology 2018 when artefacts from the European alps had been gathered together in Sion for an exhibition Vestiges en Péril curated by Pierre-Yves Nicod at the Musée d’histoire du Valais.[4] The artefacts in the exhibition dated from the Mesolithic to 20th century, and included shoes, clothes, crockery as well as weapons and tools. In addition to these identifiable objects from the more recent past, are strange misshapen wooden forms. Nicod explained to me that many of these are enigmas. It’s not known what they were but it is known that they were made by human hand.

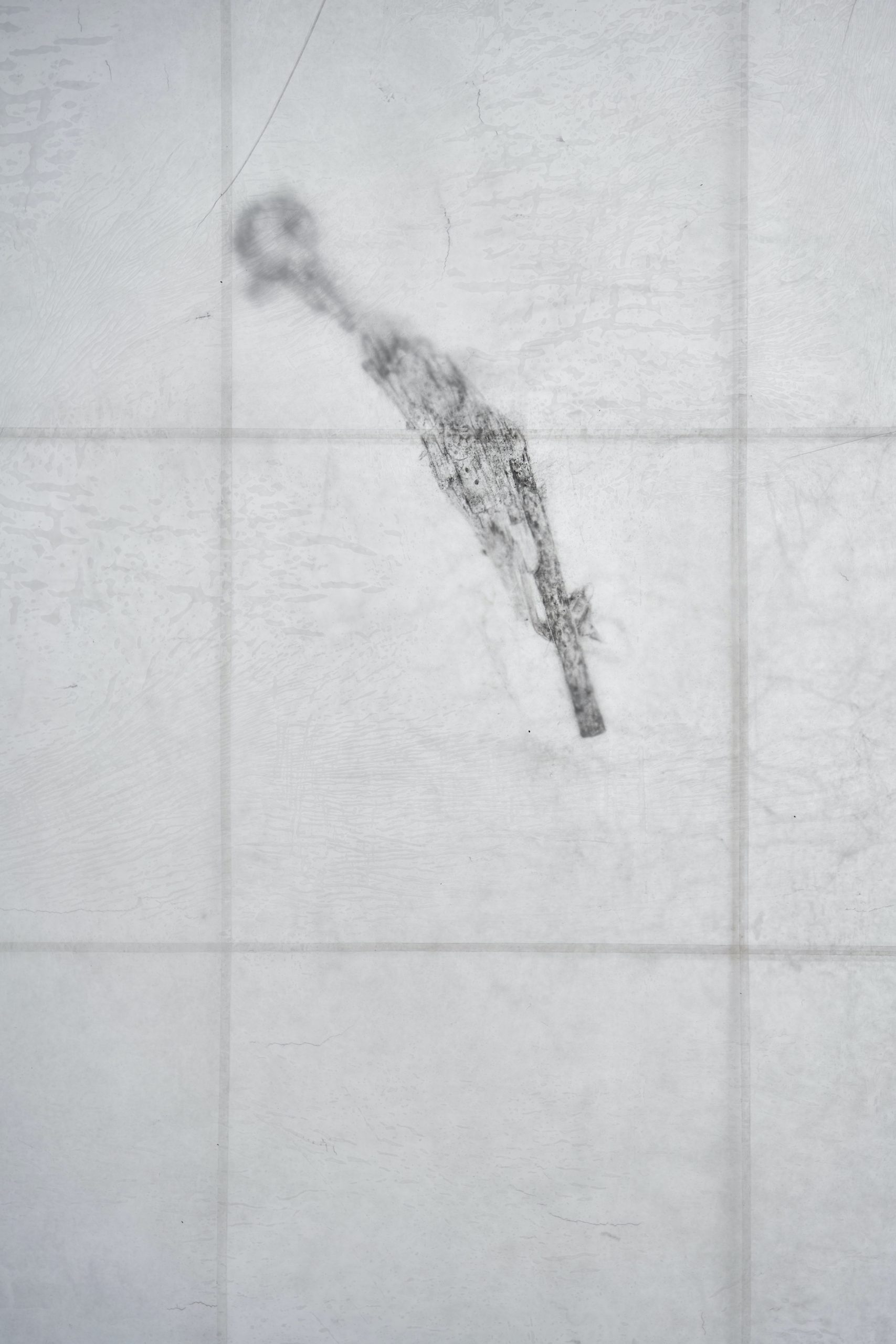

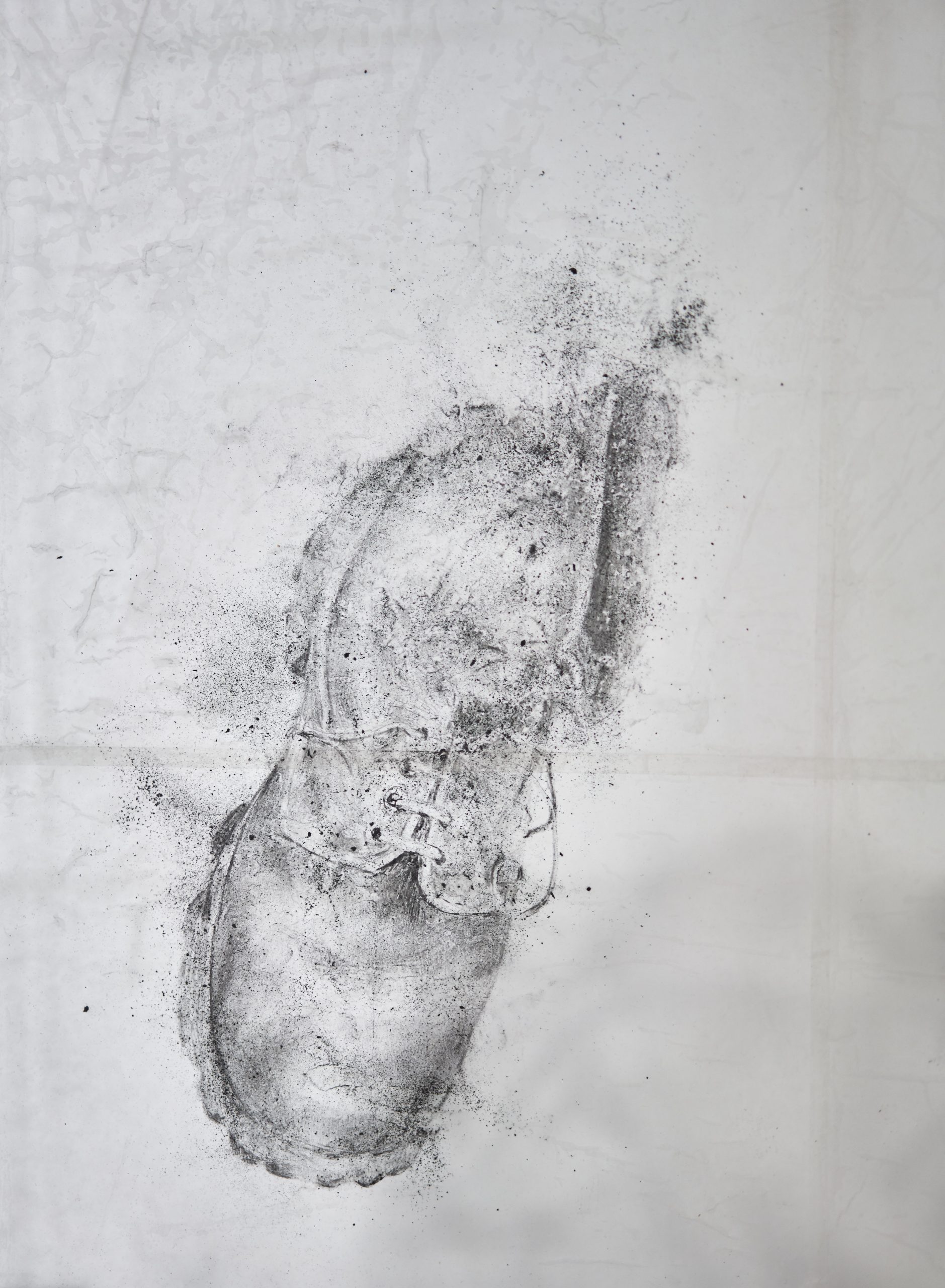

And so began an exchange with Nicod, and a series of research visits 2019-2022 to study collection finds at Sion, Annecy, and Bern. This involved slow careful sketchbook studies of the artefacts attempting to delineate their details and get a sense of their materiality, using drawing as a proxy for touching. Back in the studio, my task was to identify a way to manipulate materials and technique to embody the conundrums of these artefacts, i.e. their material precarity, the fact that they are revealed through loss, a sense of layering with other time periods.

The resultant drawings, exhibited for the first time at Drawing Projects UK, are made by trapping graphite dust between sheets of waxed paper. These sheets are so thin that they are almost transparent, like looking through misted glass. One sheet is laid flat on to a large studio table. Then, using a stick of watersoluble graphite, particles are shaved off onto the surface of the paper, leaving a dusty residue. The slight tackiness of the wax helps it adhere. Occasionally an addition of water, or pressure helps manipulate an image, taking on the form of one of the glacial artefacts. The graphite dusts builds up, creating thicker piles of dust in the areas of the drawing that require most shadow. At this stage, there is extreme precarity. I hold my face as far back as possible, so that my breath doesn’t disturb these vulnerable unfixed ‘marks’ – or rather, ante-marks, the arranged pigment that will become marks.

The next stage involves trapping this layered dust between the two paper skins. The second sheet is laid carefully over the first. The movement of down draft disturbs the particles, they puff outwards slightly, a diffused mark, as if the image has been dropped from a height into soft powder, or as if its substance, the particulate of its matter, is visibly, eroding seeping into its surroundings.

Finally, heat. The drawings are to be made (and by ‘made’ I mean become fixed) with heat. The image is suspended in place by melting the two skins of waxed paper to encase them. Running a hot iron over the surface fuses the skins together. The resultant surface takes on a reflective sheen with craquelure reminiscent of ice. The soluble graphite becomes liquid in the molten wax and in places pools, bubbles and becomes dark. Pigment is fused with wax. Under the agency of heat, an entanglement called drawing.

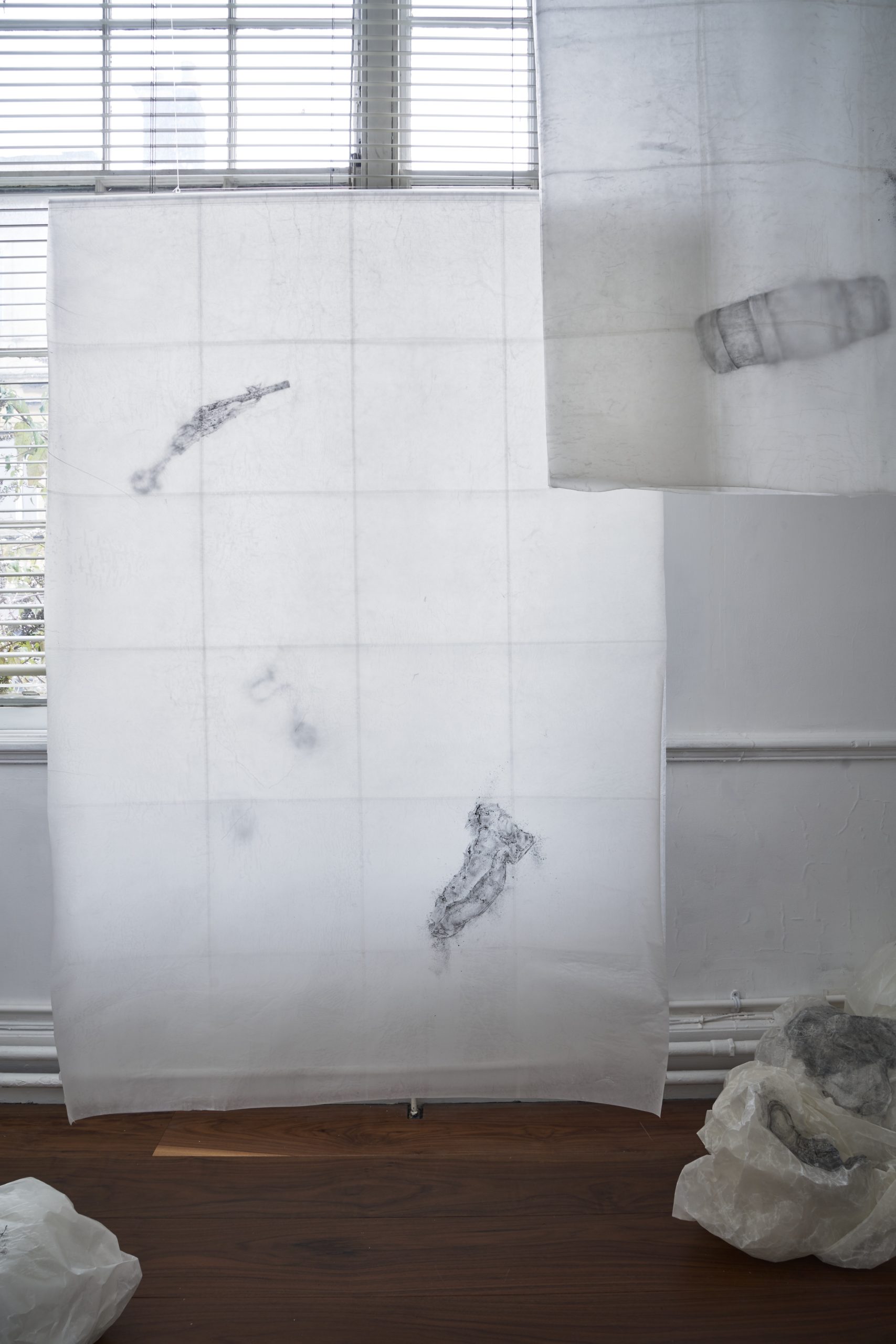

The image floats there. Lifted from the table and hung in space, the object appears trapped in ice. The darkness and tonal values of the drawing suggest an illusory solidity – the objects peer out of the page as if hidden behind it. But there is no behind. Only the wafer-thin surface. When several drawings are layered over one another other, the lower layers become hazy, like shadows of something out of reach. As if buried deeper. The drawings enact a fanciful stratigraphy. Imagining the jumble of objects layered in the ice. Bound together in relationships that shift over time. Unlike terrestrial burials, a glacier is not at rest. It is an icy river, pulled by the forces of gravity and erosion.

The composition of these layered drawings is also contingent. The sheets can be layered up interchangeably. Different objects coming to the fore, as if jostling for attention at the surface. There is perhaps no one single drawing here. The drawing is the relationship between the parts, the arrangement temporarily composed. This openness can be found in the material make-up of the individual sheets. Fixed by heat, suspended in the page. It is only the melting of the wax that holds the pigment in place to make an image, to make the shift from matter to drawing. But this is an unstable support. Wax, like ice, melts. The drawing remains subject to environmental forces – heat from the sun, domestic heating devices, light. Subjected to heat, wax, like ice, will return to its molten state. These drawings are only temporarily held. When heated, the sheets will become unstuck, the graphite become liquid in the molten wax, allowing it to run and pool, or smear away as the support disintegrates.

This sense of vulnerability to damage is accentuated in the gallery display. While the layered hanging suggests a limbo, of being poised between one state and another, on the floor beneath lies a mass of other drawings crumpled up into a three-dimensional topography. The form at once evokes mountainous terrain and icy crevasses. The crumpled paper clearly recalls discarded waste, the screwed-up paper ball tossed away. The crumpling is a counter intuitive step to take in drawing, after spending hours of time and care in its production. The crumpled ball is a visual signifier of the unwanted and discarded; here it is deliberately engaged in the drawing to gently probe values of finish and care. Does something on the verge of loss become more coveted? Would it matter if the drawing were to be destroyed all together? Or has the drawing not been lost at all but is now in a changed state, as in ice to water?

***

Drawing as an artform has long held association with the ephemeral, both in its material conditions and capacity to make visible images and ideas. Traditionally made on paper, drawings were vulnerable to atmospheric conditions, sensitive to both light and humidity. In conventional circumstances, damage to drawings is avoided. To protect them, works on paper would be framed behind glass, or stored away from sunlight to enhance their longevity. This materiality is generally coded as positive: the intimacy and care that viewing demands has contributed to constructing a kind protective aura around drawings. A 2009 exhibition devoted itself to this very theme arguing: ‘what is most compelling about works of art on paper: their inherent fragility and their particular brand of quiet intimacy’.[5] Elsewhere, it has been argued that the ‘insubstantiality of drawing has a particular from of visuality that provokes in us a peculiar response’.[6] It is this capacity of the materiality of drawing to provoke a response that the Emergency! project explores.

Drawings are often discussed in terms traces, particularly how they bear the trace of a maker, or more recently, the traces of non-human agency that contribute to its making. In both cases, the message is that a drawing bears its making on its sleeve. It is its own form of archaeology, a record of the making process.[7] Philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy wrote that drawings are in a state of becoming, of opening up, a drawing as a ’suspension of achieved reality’.[8] Implicit to this conception of drawing is a sense of movement and futurity. I take from this the idea that a drawing is not final fixed entity, it gestures towards its own future and the potential of what might happen to it. Specifically, in the context of the Emergency! work, the more materially vulnerable a drawing appears to be, the more aware we are of the threat to its future. And just as its making is recorded in a drawing, so too can its ‘unmaking’, as it accrues the marks of its ongoing existence and decay. Like the changing ecologies of mountain environments, drawings change over time. Ink fades, creases deepen, paper yellows. You see, it’s a fallacy that drawings mark, or fix, in as much as they themselves are not stable. They, like us and the world around us, are in a state of change, subject to the entropy of time to which we will all succumb.

What Emergency! does, is acknowledge this uncertainty, to the vulnerability of not knowing what forces are at play, both in glaciers and drawing. This quality is approached not as a weakness to be avoided, but as a potential agent to make meaning in the drawing. The Emergency! work seeks to highlight this state of flux and look at how it might be harnessed to reflect upon other states of precarity in the world – in this case the human and environmental challenges found in glacial archaeology.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Pierre-Yves Nicod, archaeologist and curator at the Musée d’histoire du Valais, for welcoming my artistic enquiry, spending time and care helping me understand the glacial artefacts. I am grateful for his ongoing support and generosity in sharing information and contacts that have made this work possible. Thanks also to archaeologists Regula Gubler and Marcel Cornelissen and Philippe Curdy for their insights into glacial archaeology.

This essay was first published in the exhibition catalogue Emergency! edited by Sarah Casey (Trowbridge: Drawing Projects UK, 2023) pp.18-27.

[1] The word for a rock that has been moved out of its original context by glacial action then deposited as ice melts.

[2] Curdy, Philippe and Nicod, Pierre-Yves, ‘An Enigmatic Iron Age Wooden Artefact Discovered on the Col Collon (3068m a.s. l., evolène, ct. Valais/ch)’ in Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt Jahrgang 50:4 (Mainz: Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums, 2020) pp.497-512. English Translation. Clive Bridger ( p.497)

[3] Gubler, Regula. Archaeology of the Schnidejoch Translated by Andrew Lawrence. (Bern: Service archéologique du canton de Berne, 2019)

[4] Mémoire de Glace Vestiges en Péril, Le Musée d’histoire du Valais, Sion, 6 October 2018- 3 March 2019.

[5] The Darker Side of Light Arts of Privacy 1850-1900 Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, from April 5 -June 28, 2009.

Powel III, Earl A., ’Director’s Foreword’ in The Darker Side of Light Arts of Privacy 1850-1900 ed. by Peter Parshall (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2009) pp.vi-vii. (p.vi)

[6] Ginsborg, Michael, ’Introduction’ in The Centre For Drawing the First Year, ed. by Angela Kingston (London: Wimbledon School of Art, 2001) pp.7-10. (p.9)

[7] Godfrey, Tony, Drawing Today Draughtsmen in the Eighties (Oxford: Phaidon, 1990) p.9.

[8] Jean- Luc Nancy, The Pleasure in Drawing, translated by Philip Armstrong (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013). p.1-3

Emergency! Installation view of Emergency! Two times and Shot at Drawing Projects UK 2022

Emergency! Shot (detail)  Emergency! Spectacle Bootliners Comb and Beads (detail) 2022

Emergency! Spectacle Bootliners Comb and Beads (detail) 2022

Emergency! Doumoulin Boot (detail) (2022)