Some Uses of Cloud

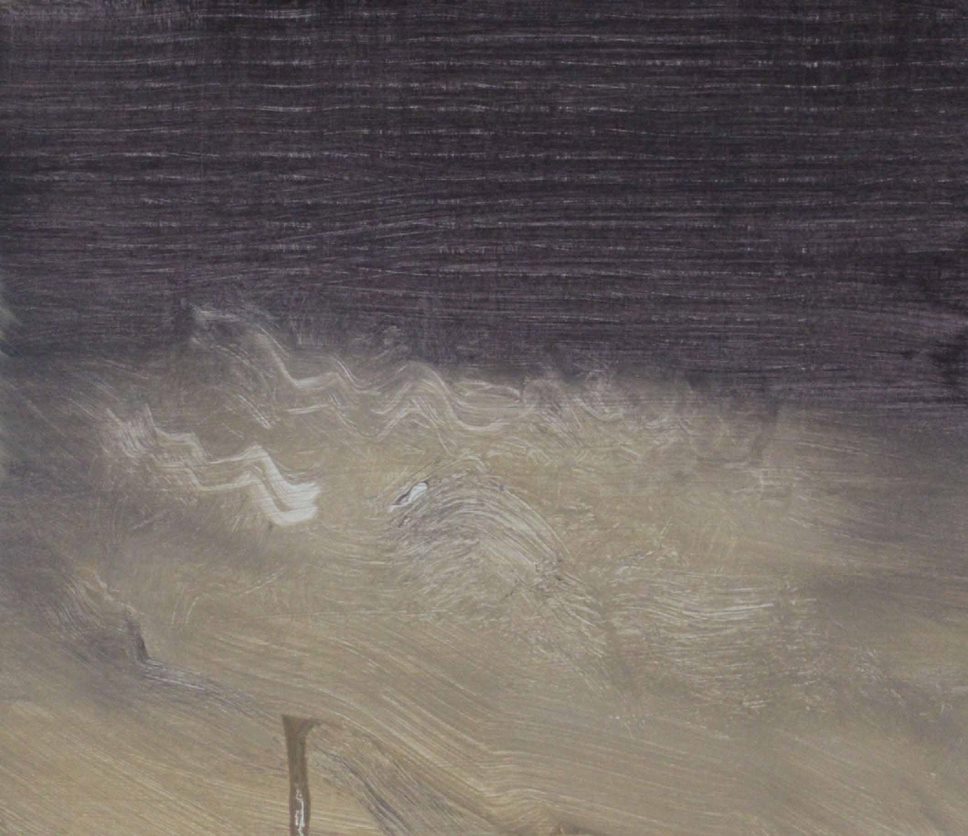

Pip Dickens’ recent cloud paintings refer to cloud forms but are not to do with meteorology. Freighted with evocative or mysterious references –a skull, a support for what seem like candles, a place where tear-drops emerge, marks that might suggest a rocky landscape, even a duckling– these cloud-shapes are more like apparitions than recorded perceptions. The viewer is invited to wonder whether the images, resembling ectoplasmic manifestations, are drifting towards solidity and longevity or will soon dissipate, leaving nothing behind.

Dickens’ paintings connect to historical and contemporary topics in painting. The most important work on clouds in visual art in recent times –A Theory of /Cloud/ (1972/2002) by Hubert Damisch– touches on both. The notes below briefly explore some of these themes. Dickens’ images inevitably recall earlier cloud representations and ideas, and their long, diverse history in art. Perhaps the most common, everyday image of a cloud is the low altitude stratocumulus with its familiar cauliflower-shaped outlines, sometimes suggesting domes or rounded hills but with a darker horizontal base. Yet meteorologists, still using the classification devised by Luke Howard in 1802, describe many other varieties with dramatically different appearances. For example, cirrostratus clouds are thin, translucent skeins of ice crystals formed between 20,000 and 40,000 feet. Nimbostratus clouds on the other hand are mid-level, thick grey blankets of rain-bearing moisture capable of blocking out significant amounts of sunlight. So one curiosity about clouds is their great variety of appearance. Is the multiplicity of cloud forms sufficient to deprive them of the right to a single name? Damisch quotes from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593) that ‘without knowledge of the name it is not possible to accede to knowledge of the thing signified’ (quoted p. 57), hinting at the capacity of cloud forms to disturb seemingly settled orders of representation and knowledge founded on the resemblance, projected by a defining word, between the image and an idea of the thing signified.

A second feature of clouds is their incessant, endless mutability. Even as we watch they appear, thicken and blossom, coalesce, accumulate, pile-up, then are dispersed and thinned, losing form and substance, eventually to disappear. This mobile spectacle is also a striking disclosure of sunlight. The sun’s rays sometimes illuminate clouds dramatically from the side or below, making them seem solidly monumental. At others their gauzy films capture and hold light in droplets of moisture ‘bearing fire in their own bosoms’ as John Ruskin put it, and scattering it across vast planes. They can disperse, polarize and reveal light but also absorb and smother it, casting ominous, premonitory shadows. The allure of such displays often comes from the disproportion between an ordinary earthbound scene below and a dramatic backcloth of towering aerial forms. In The Bright Cloud (1833-4, Tate Britain) by Samuel Palmer, for example, the rounded shapes of billowing clouds, which occupy most of the upper third of the picture plane, are echoed by the shapes of trees, hillside and sheep, bringing an enigmatic harmony to a bucolic scene.

In Europe clouds feature in Jewish, Christian and pagan stories, and so eventually show up in their visual representation. 1 Damisch observes how clouds came to organise spacial relations between the human world and the divine kingdom, from the sixteenth century onwards serving as cushions, seats, balconies and platforms. In the most ambitious examples of Baroque tromp l’oeil, for example Correggio’s Parma frescoes, views of real architectural spaces are negated, the dome of the cathedral being replaced by a tunnel of space lavishly decorated by clouds affording the upward gaze of the viewer a glimpse of heaven. Clouds have also offered a means of transport between earth and heaven; angels hover or descend while the saintly are carried aloft. Medieval artists ‘never painted a cloud but with the purpose of placing an angel upon it’ while today, Ruskin observes, we have so disenchanted them that they signify only ‘so many inches of rain or hail’. (Quoted in Damisch, p. 187) Yet for Ruskin our capacity to perceive the beauty of skies and clouds, ‘the glory of the Sun and Moon for human eyes’, unfolds a life-giving truth. What so deeply disturbed him about historically new, ominous ‘plague-clouds’ he thought he began to see around 1875 was precisely a threat to this inestimable gift.2

Clouds have served the purpose of allegorical allusion in painting. At the upper left of one of Mantegna’s three depictions of St Sebastian (1457-59, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) a white cloud is shaped to show a horse and rider, suggesting perhaps a figure from St John’s apocalypse or even the destructive power of time itself. Turning to the visualisation of mythological and religious stories, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses Jupiter created a haze in which he hoped to hide from his jealous spouse Hera the rape of Io. In his telling analysis of Correggio’s erotic and disturbing Jupiter and Io (c. 1530, also in Vienna) Damisch reflects on the potential of cloud and formless, blotchy shapes more generally to stimulate the artist’s imagination. For Leonardo, day-dreaming, musing on amorphous, indistinct shapes and tones like stains and clouds, could helpfully suggest ‘mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, great plains, valleys and hills…battles, and lively postures of strange figures, expressions on faces, costumes and an infinite number of things’ (quoted in Clark 1988, p.135). Imaginative projection onto deliberately made stains and blots as a technique useful to artists was proposed by Alexander Cozens in 1785. The suggestions, even ‘information’, available from amorphous shapes was claimed to enhance the powers of the artist to create what he willed, but might also, however, reveal darker preoccupations, apparent in the projection of fetishistic fantasies.

Techniques of ‘seeing in’ cloud-like forms can be contrasted with techniques of observation and recording. Transience and constant change make clouds a demanding subject for representational drawing and painting because neither in form nor position do they remain helpfully still. Yet this difficulty was eventually seen by different artists as an opportunity to sharpen scrutiny and improve rendition. Here then, if tamed by method, clouds may be brought to serve the ends of representational veracity.

Yet as Damisch puts it, a cloud ‘is a substance with neither form nor consistency, onto which Correggio imprints emblems of his desire, just as Leonardo before him, imprinted his onto the stains on a wall.’ (ibid, 31-2) This touches not only on the seductiveness of the indeterminate, the attractiveness of what escapes graspable shape, seeming to embody limitless life. As Peters and Piechocki (2021) remind us, in classical Greece clouds tended to be given a female gender, and linked in their constant ‘becoming’ with a capacity to give birth, not only to rain, thunder and lightning but also in the medieval period to frogs and fish. In Aristophanes’ play Clouds the female chorus appears in the costume of clouds. Socrates, the target of the satire, remarks that ‘clouds can turn into anything they want’, underlining their power to provoke, even direct, the spectator’s imagination. In this light clouds not only personify poetry itself but also connect to an idea of the origins of creativity in the passions, the psyche’s endlessly changing forms, perspectives, objects of desire, only some admissible by the subject. Well-known surrealist techniques, like frottage and fumage, producing evocative cloudy, smoky or indistinct surfaces, were designed to allow contact with the unconscious by evading mechanisms of self- censorship.

Damisch subtitled A Theory of /Cloud/ ‘Towards a History of Painting’, suggesting a contribution to an as-yet unfinished project. His argument is that the painting of cloud-forms (or/cloud/) played a decisive role in a sixteenth century revolution in European painting, introducing a new type of pictorial space, dethroning drawing and eventually freeing and exalting colour. Painter-theorists of the High Renaissance, like Brunelleschi and Alberti, devised the foundations of a systematic, horizontally-oriented linear perspective, while artists in Northern Europe worked incrementally towards a similar pictorial order. Damisch agrees with other historians that the aesthetics of the period ranked drawing far above colour. Human and divine figures were to be judged against known norms or ideals of beauty, right proportion and harmony, and had to be presented frontally and clearly for such correspondence to be visible. The revolution in painting initiated by Correggio, later identified with the Baroque, breaks decisively with an outlook in which solid, impermeable objects with clear, fixed outlines were judged uniquely suited to the linear powers of drawing. Painting is set upon a path in which colour is finally recognized as an independent element or ‘force’, until Matisse is able to say in a 1904 letter to Signac that drawing and colour were ‘completely different, even absolutely contradictory’. Drawing ‘relies on linear or sculptural form’ while painting ‘relies on coloured plasticity.’ What Matisse presents as an opposition means that ‘the painting, especially when it is applied in small dots, destroys the drawing.’ (Amory and Dumas 2023, 161) Damisch believes that cloud as a painterly device is decisive to this process.

In sum, as well as offering a daily spectacle of polymorphic beauty clouds gather around themselves a rich accumulation of associated ideas. The briefest glance at the history of clouds in art, not to speak of the insights and erudition of Damisch, reveal remarkably strong links to painting’s enduring themes and topics, like line and colour, ephemerality and duration, materiality and spirituality, the sublime and the prosaic, concealment and revelation.

Ian Heywood. 2023.

Notes

1 For comments on Catholic theology and the use of images see Damisch 47-53. For Ruskin’s theology of clouds see ‘The Firmament’, Chapter VI, Modern Painters Vol. 4, pp 106-114.

2 See Ruskin ‘The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’. Also Nicholas Robins (2021), ‘Ruskin, Whistler and the Climate of Art in 1884’.

References

Amory, Dita and Dumas, Ann (2023), Vertigo of Colour: Matisse, Derain and the Origins of Fauvism, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Clark, Kenneth (1988) Leonardo Da Vinci, introduction by Martin Kemp, London: Penguin Books.

Damisch, Hubert (2002) A Theory of /Cloud/: Towards a History of Painting, trans. Janet Lloyd, Stanford: Sanford University Press.

Peters, Jeffrey N. and Piechocki, Katharina N., ‘Early modern clouds and the poetics of meteorology: An introduction’, Romance Quarterly, 68:2, 65-78 (2021).

Robins, Nicholas (2021), ‘Ruskin, Whistler and the Climate of Art in 1884’, in Ruskin’s Ecologies: Figures of Relation from Modern Painters to the Storm-Cloud, edited by Kelly Freeman and Thomas Hughes, London: Courtauld Books Online. https:// courtauld.ac.uk/research/research-resources/publications/courtauld-books- online/ruskins-ecologies-figures-of-relation-from-modern-painters-to-the-storm- cloud/ Accessed September 2023.

Ruskin, John (1884/1904) ‘The Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’ in The Works of John Ruskin, Vol. 34, edited by E.T. Cook and A. Wedderburn, London: George Allen.

Ruskin, John (1904) Modern Painters, Volume 4, in The Works of John Ruskin, Vol. 6, edited by E.T. Cook and A. Wedderburn, London: George Allen.