Once is Not Enough #1. 2019. Newcastle University.

Forty five paintings on linen – Timber construction.

Once is Not Enough #3. 2022. Bridewell Gallery, Liverpool.

Once is Not Enough #3. 2022. Bridewell Gallery, Liverpool.

Once is Not Enough #4 (Solaris Suite). 2023. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

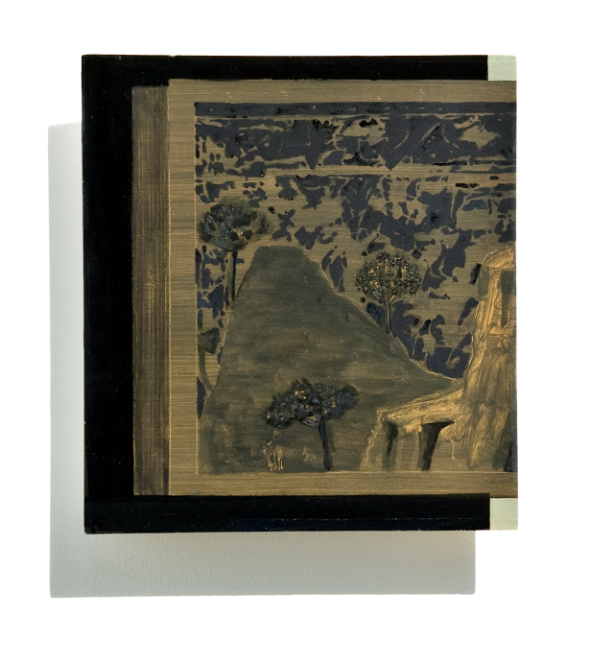

Repetition from Reproduction (after Giotto). Oil on Linen. 28cm x 26cm. 2020.

Repetition from Reproduction (after Picasso). Oil on Linen. 28cm x 26cm. 2022.

Repetition – Difference – Timelessness – Oliver Hardy

Dr James Quin

No device more effectively generates the effect of a doubling or bending of time than the work of art, a strange kind of event whose relation in time is plural.[1]

___Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood.

Repetition is an everyday word that encompasses an extravagant range of enterprises; alliteration, appropriation, close copy, strict copy, duplication, ingemination, palilogia, reiteration, simulacrum, and I could go on. I have been asked on many occasions – why repeat? What can possibly be gained by repetition that has not already been seen? In response, and in agreement with Briony Fer, a far more interesting question is what might the world look like ‘without recurrence, reiteration, repetition’ – without the already seen?[2] The answer to this question, I suspect, would be an incipient world of endless difference without any possibility for recognition – an infinite and dizzying assault on the senses by the new. Repetition in the world, however, is ubiquitous, an engine of difference that creates the possibilities for the new to emerge from the already seen, a process central to painting in the Western tradition. One of Gilles Deleuze’s claims is that repetition always results in difference and never the same. While I agree with Deleuze’s claims for the power of repetition, it is nevertheless a claim that continues to split opinion within art historical discourse.[3]

The pejorative associations that continue to haunt repetition are so entrenched, that doubt and uncertainty are confronted not only in the studio, but in the act of writing this text. As I write I have an eye on that most academically unacceptable class of repetition; plagiarism. In writing about repetition, I risk not only repeating myself, but also the work of others. In my studio, another eye checks the progress of painting, determining the degree to which they produce a difference in kind and not of degree.[4] The key to success when repeating is to repeat with difference. A successful repetition does not repeat.[5]Rather than attempting to present a thorough account of Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, and Walter Benjamin’s often contradictory writing on repetition, I will however, introduce aspects of their thinking on repetition, time and difference that are relevant to my studio practice – painting.

For the sake of consistency, clarity, and to avoid misunderstandings generated by their colloquial interchangeability I will rely (in part) on Bruce Kawin’s straightforward differentiation of constructive and destructive repetition:

Repetitious: where a word, percept, or experience is repeated with less impact at each recurrence; repeated to no particular end, out of a failure of invention or sloppiness of thought and Repetitive: when a word, percept or experience is repeated with equal or greater force at each occurrence.[6]

While Kawin’s differentiation is partially useful, the binary opposition is too comfortable, too neat. Here, for example, are two iterations of an anecdote. [7]

As the train I am travelling on pulls into the station at Newcastle upon Tyne, I remember the time I visited the City as an eleven year old. The visit was organised by my school for purposes of an educational nature. With pocket money provided by my parents, I bought from a small shop on a steep side street, a set of four near identical colour transparencies of the Tyne Bridge taken sequentially. I then remember that I always remember this – every time my train pulls into Newcastle Station.

As the train I am travelling on pulls into the station at Newcastle upon Tyne, I remember the time I visited the City as an eleven year old. The visit was organised by my school for purposes of an educational nature. With pocket money provided by my parents I bought from a small shop on a steep side street, a set of four near identical colour transparencies of the Tyne Bridge taken sequentially. I then remember that I always remember this – every time my train pulls into Newcastle Station.

The anecdote is a riot of memory, time and repetition. It is in fact a repetition of Jorge Luis Borges’ enquiry into life’s abundance of repetition from his essay A New Refutation of Time.[8]

If we apply Leibniz’s Law to these two texts, it is difficult at first glance to argue that they are separate entities.[9] They are in fact different. I made sure of it. But this is not the point. The anecdotes above are not a sequence – they are a series, albeit a small one. The terms sequence and series are used interchangeably but have distinct differences. A sequence is usually thought of as an ordered list of numbers or terms where the order of the numbers or terms is important. A series is the sum of the terms in a sequence and the order of these terms can vary. At the risk of a gross oversimplification a sequence can be written as 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. The sum of the series is 45, but the order of the sequence’s terms can be varied several times over without altering the sum, and can be written differently, 5 + 8 + 6 + 9 + 10 + 7, or 6 + 5 + 10 + 8 + 7 + 9, and so on. This, according to American artist Mel Bochner, is nothing more than the variation of a theme, evident in the painting of Claude Monet or Giorgio Morandi. Bochner distanced his own work, with that of Sol Lewit and Donald Judd, from what he described as the ‘series as style’.[10] Bochner differentiates the stylish series from the more masculine ‘method’, ‘attitude’, and ‘logic’ of the serial along three modes of operation.[11]While Bochner’s definitions seems to combine qualities of both sequence (‘The order takes precedence’), and the series (‘permutation, progression and reversal’), his attempt to separate series from serial remains problematic. [12]

In Gilles Deleuze’s book on Leibniz and the baroque, the series is discussed in terms of not only internal differences, but also the ways in which one series might be folded into another. Literature, to follow Deleuze, might be considered a series, as could medicine, dance, or painting, and they possess the potential to be folded one into the other. Deleuze writes:

We have seen that the world was infinity of converging series, capable of being extended into each other, around unique points.[13]

I will return to the two anecdotes introduced above and discuss them, not in terms of Bochner’s style, method, attitude or logic, but in terms of duration as thought by Bergson, and difference developed from Leibniz, by Deleuze. The second anecdote is different to the first. They would, however, according to Bergson, still be different even if I had not manufactured the difference. The difference would be qualitative, and not quantitative. The act of repetition alters perception of the first anecdote. The anecdote’s second appearance marks a temporal difference from the first, and in this qualitative difference over time, we are made aware of time flowing by qualities that differ at different times. The difference that the anecdote’s second iteration performs is an internal difference (a mobility of consciousness), central to Bergson’s Pure Duration, and not the discovery of difference by comparing the two anecdotes as they occur in space. The repetition of the first anecdote, according to Kawin’s definition, is ‘repeated to no particular end, out of a failure of invention’, and is repetitious. This is too simple.[14]If we think of the second iteration of the anecdote from Bergson’s perspective, repetition produces an internal difference that relies on the perception of the two iterations as they occur in time. Memory of the first must be held in mind in order to account for the second. The elements of identity are therefore memory and repetition. Bergson writes,

It is duration that includes all the qualitative differences, to the point where it is defined as alteration in relation to itself….Memory is essentially difference and matter essentially repetition.[15]

In the Essai, Bergson refers to this as confused multiplicity, a multiplicity radically different to that encountered in space. The comparison of my two anecdotes may take place in space – does the arrangement and spelling of words correspond exactly in both? Bergson defines this as distinct multiplicity, the counting and manipulation of things that exist in space. Confused multiplicity has nothing do whatsoever with space or number, but with the radical force of time that appears as pure duration. The relevance of Bergson’s pure duration to a distinction between sequence and serial is that it implies a temporal synthesis that challenges the temporal order of past-present-future. Pure duration to follow Bergson, challenges the idea of temporal succession (the sequence), by thinking duration as a force in which past, present and future coalesce (the series). At the risk of oversimplification, difference to Bergson and Deleuze is not a concept but another name for being. Being, however, is not static; it is an ongoing process, one that unfolds as a process of differentiation. Three discourses that help interrogate unfolding differentiation underpinned by repetition are encountered in the writing of Walter Benjamin, Jacques Derrida, and Gilles Deleuze.

A reader of Walter Benjamin’s language translated from the German into English will be aware of a preponderance of the suffix – specifically the suffix -ability (barkeit). The most well known of these barkeiten is perhaps Reproduzier-barkeit (Reproduce-ability).[16] Benjamin’s recourse to this suffix performs a similar temporal function to the Zeitwort (time- word or verb) in that it signals an unfinished or ongoing process. Benjamin clarifies the abilities of this unfinished process by introducing the term extreme. A property that Leibniz ascribes to the monad and one that helps determine Benjamin’s extreme, is that the singular contains the universal.[17] Benjamin’s extreme describes a things potential or -ability to ‘part company with itself’, a process whereby the singular becomes a plurality, and virtual potentials become actualised.[18]Benjamin’s term extreme can be thought of as the means by which multiplicity might be released from an original, through an internal process that remains virtual until it is released through repetition. Samuel Weber in Benjamin’s -abilities explains,

The uniquely extreme in no way excludes repetition: as a “virtual re-arrangement” it presupposes it. But it also determines it as a movement of differentiation, of variation, of alteration.[19]

Here Weber agrees with Deleuze. Variation lies at the heart of repetition, and repetition can only be understood in light of this inextricable link between repetition and difference. Deleuze clarifies this in the preface to the English edition of Difference and Repetition:

[Variation] is not added to repetition in order to hide it, but is rather its condition or constitutive element, the interiority of repetition par excellence.[20]

The presupposition of repetition in Benjamin’s extreme resembles Jacques Derrida’s principle of iterability. Though not identical, they both question the either/or of possibility/impossibility. The ability for a single occurrence to multiply itself in advance undermines this binary logic. Iterability is not in and of itself repetition; it is closer to Benjamin’s ability – the potential for something to be repeated as a structural possibility already at work in the original.

Derrida, like Benjamin and Deleuze, maintains that repetition is always inscribed in an original and that in order for an original to function as a carrier of meaning, to continue speaking, it must be able to be repeated. If not, any uniquely original image would exist outside of symbolic register and its ability to transmit meaning would be nullified. Without precedence we simply would not know what we were looking at. In Limited Inc, Derrida writes,

If one admits that writing (and the mark in general) must be able to function in the absence of the sender, the receiver, the context of production etc., this implies that this power, this being able, this possibility is always inscribed, hence necessarily inscribed as possibility in the functioning or the functional structure of the mark…It follows that this possibility is a necessary part of its structure…Inasmuch as it is essential and structural, this possibility is always at work marking all the facts, all the events, even those that appear to disguise it. Just as iterability, which is not iteration, can be recognised even in a mark that in fact seems to have occurred only once. I say seems, because this one time is in itself divided or multiplied in advance by its structure of repeatability.[21]

This property of multiplicity ‘in advance’ is a temporal condition of an image that can no longer be described as strictly static.[22] It has the potential to be mobile in time through repetition. This mobility, the ability to multiply forwards, also possess properties that help address the question of how the temporal conditions of the static image might be shifted or re-positioned.

Repetition troubles normative temporal flow. The then becomes a now anticipating a next in contrast to a now passing into a then in order to make room for the next. In Deleuze’s 1968 principle thesis for the Doctorat D’Etat Difference and Repetition, the relation between the singular and the multiple is discussed unequivocally in the introduction as central to the thesis. Deleuze begins his introduction with ‘Repetition is not generality’, and moves on in a vein that anticipates Derrida’s iterability, to how repetition repeats in advance its subsequent repetitions:

[R]epetition is a necessary and justified conduct only in relation to that which cannot be replaced. Repetition as a conduct and as a point of view concerns non-exchangeable and non-substitutable singularities… [Repetitions] do not add a second time and a third time to the first, but carry the first time to the “nth” power…it is not the Federation Day which commemorates or represents the fall of the Bastille, but the fall of the Bastille which celebrates and repeats in advance all the Federation Days, or Monet’s first water lily which repeats all the others. Generality, as generality of the particular, thus stands opposed to repetition as universality of the singular.[23]

Common sense dictates that if repetition entails plurality it cannot simultaneously entail the singular. But as we have seen in Leibniz’s monad, Benjamin’s extreme, and Derrida’s iterability, – repetition’s stretching of the first to its “nth” degree no longer strikes us as paradoxical. A common question asked by visitors to my studio when confronted by a series of paintings is which one came first? Deleuze’s repetition unravels temporal foundations in ways that take us into surprising territories that undermine the very idea of firstness. If I attempt to answer the question in order to move on to something less taxing, the answer might be ‘the one that I finished first’.

This answer seems to have wrapped things up nicely despite the fact that at the time of answering I do not consider any of them to be finished. The first painting that I thought of as the first could only be so if it remained the first infinitely, and therefore would be the origin of nothing at all. In order for this first painting to be the first it needs a second hung in close proximity. The strange territory I mentioned above now shows its full force. Briankle G. Chang in Deleuze, Monet and Being Repetitive clarifies the way in which repetition causes a ‘troubling murmur in the regular rhythms of numbering’.[24]Chang explains:

A remarkable consequence follows: because the first time depends essentially on its second time to appear as the origin, the first time, for all its claim to chronological priority or non-derivativeness, turns out to be not the first time but, rather the third; for it now exists in essential relation to both the second time and the supposedly first time that anchors the whole temporal sequence. [25]

In a 1993 short essay He Stuttered, Deleuze proposes that language and its temporal sequentiality, when put under stress – begins to stutter. We might assume that in the repetition of syllables it is the speaker who stutters and not language itself. Unless we are speaking metaphorically or describing things anthropomorphically, (my Compact Disc player stutters as I never clean the discs) things themselves do not stutter. Deleuze cites examples from Kafka, Melville, and Beckett in order to qualify the difference between the author who makes his/her characters stutter and language itself that stutters. A stuttering language according to Deleuze results in difference. Discussing difference in T. E. Lawrence’s language, Deleuze writes,

It is no longer the character who stutters in speech; it is the writer who becomes a stutterer in language. He makes language as such stutter: an affective and intensive language, and no longer an affectation of the one who speaks…. [He] makes the language itself scream, stutter, stammer or murmur. What better compliment could one receive than that of the critic who said of Seven Pillars of Wisdom: This is not English. Lawrence made English stumble in order to extract from it the music and visions of Arabia. [26]

I introduce Deleuze’s stutter here due to its translatability. If, as Deleuze argues, language itself stutters, stuttering is not restricted to speech and it is legitimate to discuss a visual language that stutters. To encounter my own paintings within what I have described as an open labyrinth is to come into contact with a series of paintings that stutter, return, defer closure, and in doing so undermine temporal order. These repetitions invoke an obscure Roman goddess. The goddesses name – Copia, is not only the etymological root of copy but also of abundance, plenty, resource and opportunity. She is first mentioned in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and is perhaps most familiar as the possessor of the ‘cornucopia’ or horn of plenty.[27] The double meaning inherent in the goddess’s name – of both copy and abundance might be re-written as repetition and abundance. Abundance is usually stored in a warehouse or storeroom to be used in the future. It is therefore not inexcusable to think of an original as a site of inherent multiplicity to be exploited at a future moment through repetition, and that the original cannot exist as an original without the copy. We cannot after all, identify something satisfactorily as an original until after it has been copied (made abundant). Repetition, if we follow Copia, has raided the storeroom in order to release difference.

Leaving difference to one side for a moment, I would like to turn to a similarity that has fascinated me for many years – a paradoxical property of time-based media (film) – its stillness. This fascination stems from a long interest in the stillness of painting, a medium that has been still for a much longer time than cinema. The temporal conditions of the static image are slippery, and in an attempt to clarify them I remember encounters from cinema that have stayed with me over the years. In 1977, I watched for the first time, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. From one hour and fifty minutes of footage, the image that I recall most readily is a freeze-frame at the film’s end – an image of Robert Redford and Paul Newman’s death [fig 1]. This mechanic of stillness, operating at the heart of cinema, is laid bare by Dziga Vertov in his 1929 film Man with the Movie Camera [fig 2]. The trotting white horse is stilled by using the freeze-frame, a cinematic illusion of stillness constructed from the repetition of a single image – a device also used by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s director – George Roy Hill.

Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Fig 2.

What impressed me most about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s ending was its endlessness. A cross section of time had been stretched into an infinite but changeless future. As the full colour scene took on a sepia tone, it transformed into an image resembling a faded photograph. The tableau then casts a backwards glance – exchanging a frozen present for one of the past by using the cliché of the faded sepia photograph, a device that replaces a filmic image with the imago: an effigy that preserves the presence of the deceased. At the last moment Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid escapes linear time and mimics the temporal conditions of painting in its rich agglomeration of past, present and future held within the static image. The agency of the film’s ending is its shift from future orientated movement to stillness – timelessness. I first noticed, as a young boy, timelessness as a form of outward address in an encounter with Oliver Hardy that dramatically collapsed time and space. Watching Hardy’s signature glance to camera for the first time took me totally by surprise. Hardy looked directly at me on a Saturday morning in 1975 from a Los Angeles in 1933. I found this (and still do) both an amusing and deeply shocking encounter – its affect undiminished by subsequent re-encounters with Another Fine Mess [fig 3].

One temporal condition of painting is this very ability to generate difference by transcending historical specificity and the context of its past production – to reverberate in, and haunt the present with a power that cannot be overestimated.

Fig 3.

[1] Alexander Nagel and Christopher Wood, an extract from “The Plural Temporality of the Work of Art”, Anachronic Rennaisance, New York: Zone Books, (2010), pp.17-19. In Time: Documents of Contemporary Art, (London and Cambridge: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press, 201)3, pp. 38-42, 39.

[2] Briony Fer, The Infinite Line: Re-making Art after Modernism, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), p. 1.

[3] Rosalind Krauss writes, ‘That so many twentieth-century artists should have manipulated themselves into this particular position of paradox- where they are condemned to repetition as if by compulsion, the logically fraudulent original – is truly compelling’. Rosalind Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition”, October, Vol. 18 (Autumn 1981), pp. 47-66. Both Jean Baudrillard and Hans-Georg Gadamar regarded repetitive strategies in the arts as symptomatic of the failure of representation and a bankruptcy of ideas. See Jean Baudrillard, For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, translated by Charles Levin, (St Louis MO: Telos Press, 1981), p. 81. See also Hans-Georg Gadamar, “The Speechless Image”, published in The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays, translated by Nicholas Walker, edited by Robert Bernasconi, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), p.90.

[4] I refer here to a differentiation of difference – difference in kind and difference of degree. Difference according to Bergson is a question of quantity and quality, and of multiplicity. Quantitative difference is difference by degree, is actual, and inherently spatial. Qualitative difference is difference in kind, virtual and essentially durational. See Gilles Deleuze, “Intuition as Method”, published in Bergsonism, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, (New York: Zone Books, 1991), pp. 13-37, 31.

[5] Throughout this dissertation I will be presenting examples of artists, whose work repeats successfully, and in some cases not. The successful repetition results in difference as opposed to sameness.

[6] Bruce Kawin, Telling it Again and Again: Repetition in Literature and Film, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1972), p.4.

[7] Originally written while travelling on a train to Newcastle on the thirteenth of September, 2015.

[8] ‘I never pass in front of Recoleta without remembering that my father, my grandparents and great-grandparents are buried there, just as I shall some day; then I remember that I have remembered the same thing an untold number of times already,’ Jorge Luis Borges, “A New Refutation of Time”, published in Labyrinths: Selected Stories and Other Writings, translated by James E. Irby, (London: Penguin Classics, 2000), p. 258.

[9] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s (1646-1716) law of indescernibles states that if two objects or entities share all their common properties, they cannot be thought of as separate entities. ‘X is identical with Y if and only if every property of X is a property of Y’, Julian Baggini and Peter S. Fosl, The Philosopher’s Toolkit: A Compendium of Philosophical Concepts and Methods, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), p. 100. “But it is absurd that there are two distinct things, which cannot be distinguished even by an infinite intellect”, an extract from “Leibniz’s Argument for the Identity of Indiscernibles in his letter to Casati (with Transcription and Translation)”, quoted by Gonnzalo Rodriguez-Pererya in The Leibniz Review, Vol.22, (2012), pp. 137-150, 139.

[10] ‘Serial order is a method, not a style’, Mel Bochner, “The Serial Attitude”, Artforum, Vol. 6, No. 4, (1967), pp. 28-33, 28.

[11] The modernist series and minimalist seriality share an infinite extension, but not spatial arrangement or organisation. Bochner is succinct on this point. In The Serial Attitude he deploys a modular thesis that draws heavily from emerging system theories of the late 1960’s. Bochner outlines three ‘operating assumptions’ that differentiate the serial from the series; ‘1.The derivation of the terms or interior divisions of the work is by means of numerical or otherwise systematically predetermined process (permutation, progression, rotation, reversal).2.The order takes precedence over the execution. 3. The completed work is fundamentally parsimonious and systematically self-exhausting.’ Mel Bochner, “The Serial Attitude”, Artforum, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1967, pp. 28-33, 29. For an account of systems theory See Ludwig von Bertalanffy, General Systems Theory, (New York: Braziller, 1968).

[12] What they both have in common however, is endlessness through repetition, an endlessness that undermined the temporal logic of Modernist painting as understood by a troubled Michael Fried in his 1967 essay Art and Objecthood. Michael Fried, “Art and Objecthood,” Artforum, (June 1967); reprinted in Art and Objecthood, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

[13] Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque, translated by Tom Conley, Originally published as Le Pli: Leibniz et le Baroque. (Minnesota: The University of Minnesota Press, 1993), p. 60.

[14] Bruce Kawin, Telling it Again and Again: Repetition in Literature and Film, (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1972), p.4.

[15] Gilles Deleuze, “Elan Vital as Movement of Differentiation,” in Bergsonism, (New York: Zone Books, 1991), pp.91-114, 92-93.

[16] I am indebted here to Samuel Weber’s Benjamin’s -abilities, (Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2008). See also Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, translated by J. A. Underwood, (London: Penguin Books, 2008), pp. 1-51, originally published as “Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit “published in Zeitschrift fur Sozialforschung, vol 1, (1936).

[17] Four qualities ascribed to the monad by Leibniz.

‘1. The monad, about which we will shall speak here, is nothing other than a simple substance which enters into compound, simple meaning without parts. 11. It follows from what we have just said that the natural changes of monads come from an internal principle [that they may be called active force], since an external cause would not be able to influence a monads interior. 12. [And generally it may be said that force is nothing other than the principle of change.] But besides the principle of change, there must also be a complete specification of that which undergoes the change, which constitutes, so to speak the specific determination and variety of simple substances. 13. This complete specification must encompass a plurality within the unity or simple. For as every natural change takes place by degrees, something changes and something remains; and consequently in the simple substance there must be a plurality of affections and relations even though it has no parts.’ See Lloyd Strickland, Leibniz’s Monadology: A New Translation and Guide, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), pp. 14-16.

[18] Samuel Weber, Benjamin’s -abilities, (Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press, 2008), p.8.

[20] Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, translated by Paul Patton, (London and New York: Continuum, 2004), p. xiv.

[21] Jacques Derrida, Limited Inc, (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1998), p.47.

[23] Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, translated by Paul Patton (New York and London: Continuum, 1994), pp. 1-2. First published in France as Difference et Repetition, (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1968).

[24] Briankle G. Chang, “Deleuze, Monet and Being Repetitive”, Culture Crtique, No. 42 (Winter, 1999), pp. 191.

[26] Gilles Deleuze, “He Stuttered”, published in Essays, Critical and Clinical, translated by Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), pp. 107-114. Originally published in French as Critique et Clinique, (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1993).

[27] In Ovid’s Metamorphoses the horn was wrenched from a bull’s head by Hercules. Another attribution suggests that the horn originated from the miraculous goat Amalatheia, wet nurse of Zeus, located on Mount Ida, Crete. The horn of plenty had the property of filling itself inexhaustibly with whatever food or drink was wished for. See New Larousse Encyclopaedia of Mythology, (London: Hamlyn, 1974), p. 91.