Looking Again

Keywords

un-repeating repeat pattern

mimic

transform through

repetition labour

drawing

textile performative text

Abstract

Enacting the subject of ornamentation through unfolding a deteriorating repetition within its reading, this paper is presented as a performative text. Illuminating rather than telling, key focus within the paper draws on: detail and curiosity as necessities during both the making process and audiences viewing of ornamenta- tion; the hidden and overlooked seen in domestic pattern and the rich potential for subversion; the whole versus the single, how looking and making can be akin to fractals; the un-repeating repeat or difference of the same as seen through visual rhythm disrupted by the glitch; how repetition of text transforms it into the decorative; transformation through repetition connected to the joys of labour and its associate cousins of repeated action, making, boredom, rhythm, muscle memory, sex.

- (i) Subtle slippages between the expected, minor moments found in the comings and goings of everyday life, discovered only through close observation, looking again. Attention and curiosity are needed to uncover these moments. Only through investing time and truly looking are details revealed. Hidden in plain sight, the domestic {whether pattern or object} is so familiar we forget to look at it. To really look, to pay attention to what is in front of us all the time. It sees you, but do you see it?

- (ii) Can’t see the wood for the trees.

Living in a log cabin in the American outback, she can’t see the wood for the trees; she is blind to anything but the forest, blinded by the forest.The trees perme- ate everything, are too close without any edge. But what if one can’t see the trees for the wood – only the big picture and no detail, a single mass of forest but not a single tree. How would you know what a forest is made from?The importance of being able to oscillate between the two is significant to understanding: seeing both forest and trees. - (iii) But what of these trees – is this all one sees? How about further details found in those woods: the bear, fox, bird, squirrel, leaf, flower, bee, ant. But then looking too closely, nothing is seen . . . . . it dissipates into pixels. But what is that pixel, a beautiful stitch, a line, a mark.

Step back to see the whole and the detail disappears, move closer and the whole vanishes. When no detail is there, guess-work and structure are laid in place where the image usually is. Back and forth until perhaps something is captured, held onto, made real. - (iv) Similar to a fractal process of perspective zooming in and out of the work: the viewer steps back for the long overview, moving closer for the individual view, further in for a detail view and so on.

This is comparable to the experience of site itself; like the fractal zooming in and zooming out of each layer {whether it be a building, room, wall, installation, artwork, object, image, line, stitch} is new and unique yet all telling a similar story. - (v) Flowing, between meaning and image the repetition of drawn words transforms them into the visual.

Similar to calligraphy the textlines are intended to be visual while retaining some legibil- ity. Fluxing between meaning and image the textlines are meant to ‘convey complexities of content without necessarily always spelling out the content for the viewer.’

An Un-Repeating Repeat or Difference of the Same

(i) Subtle slippages between the expected, minor moments found in the comings and goings of everyday life, discovered only through close observation, looking again. Attention and curiosity are needed to uncover these moments. Only through investing time and truly looking are details revealed. Hidden in plain sight, the domestic {whether pattern or object} is so familiar we forget to look at it. To really look, to pay attention to what is in front of us all the time. It sees you, but do you see it?

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So it adapts, mimics, copies, duplicates, replicates, clones, fakes, counterfeits, impersonates, simulates, mirrors, echoes, parallels, retells, recites, restates, iterates, the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the origi- nal. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother instilled in me the love of making while watching her in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather showed me a love of‘writing’through his use of calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with indi- vidual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(v) Flowing, between meaning and image the repetition of drawn words transforms them into the visual. Similar to calligraphy the textlines are intended to be visual while retaining some legibil- ity. Fluxing between meaning and image the textlines are meant to ‘convey complexities of content without necessarily always spelling out the content for the viewer.’

(viii) Blown up, Sweet Stag, curled up in the corner on a small green mound, gentle cross-stitch gives the 3-inch animal enough structure to hold him. But then BOOM, expanded to life size he encounters difficulty in both the stitch and the animal; he does not like to grow. Pixelated now beyond his appealing smaller self a grotesque creature is formed. From far off he still retains a trace of his smaller self but as you approach this begins to falter. Oscillating between a stitch, a pixel, a line, a thread the Stag is mimicking as best he can. But up close he disinte- grates back into the component units that make him up.

Pattern – Familiar – Domestic

(i) Subtle slippages between the expected, minor moments found in the comings and goings of everyday life, discovered only through close observation, looking again. Attention and curiosity are needed to uncover these moments. Only through investing time and truly looking are details revealed. Hidden in plain sight, the domestic {whether pattern or object} is so familiar we forget to look at it. To really look, to pay attention to what is in front of us all the time. It sees you, but do you see it?

(ix) Pattern and line accumulate into words, repeated over and over. Words and letters dissolve into pattern, repeated again and again. The action of making embedded; repeating a line, a word, a letter. Focusing on drawing a single letter annexes it form the word, dissipating meaning.

(vii) My grandmother instilled in me the love of making while watching her in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather showed me the love of ‘writing’ through his use of calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(v) Flowing, between meaning and image the repetition of drawn words transforms them into the visual. Similar to calligraphy the textlines are intended to be visual while retaining some legi- bility. Fluxing between meaning and image the textlines are meant to ‘convey complexities of content without necessarily always spelling it out the content for the viewer’.

Copy – Mimic

(viii) Blown up, Sweet Stag, curled up in the corner on a small green mound, gentle cross-stitch gives the 3-inch animal enough structure to hold him. But then BOOM, expanded to life size he encounters difficulty in both the stitch and the animal; he does not like to grow. Pixelated now beyond his appealing smaller self a grotesque creature is formed. From far off he still retains a trace of his smaller self but as you approach this begins to falter. Oscillating between a stitch, a pixel, a line, a thread the Stag is mimicking as best he can. But up close he disinte- grates back into the component units that make him up.

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So, it adapts, mimics, copies the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother instilled in me the love of making while watching her in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather showed me a love of‘writing’through his use of calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writ- ing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(ix) Words and letters dissolve into pattern, repeated again and again. Pattern and line accumu- late into words, repeated over and over. The action of making embedded; repeating a line, a word, a letter. Focusing on drawing a single letter annexes it form the word, dissipating mean- ing.

(v) Flowing, between meaning and image the repetition of drawn words transforms them into the visual. Similar to calligraphy the textlines are intended to be visual while retaining some legi- bility. Fluxing between meaning and image the textlines are meant to ‘convey complexities of content without necessarily always spelling out the content for the viewer.’

Tradition – Nostalgia

(i) Subtle slippages between the expected, minor moments found in the comings and goings of everyday life, discovered only through close observation, looking again. Attention and curiosity are needed to uncover these moments. Only through investing time and truly looking are details revealed. Hidden in plain sight, the domestic {whether through reoccurring events or tradition} is so familiar we forget to look at it. To really look, to pay attention to what is in front of us all the time. It sees you, but do you see it?

(vii) Mommom taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio as I think of it} and Poppop taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be educated, he could at least look it.

(ii) Can’t see the wood for the trees. (while) living in a log cabin in the American outback, she can’t see the wood for the trees; she is blind to anything but the forest, blinded by the forest. The trees permeate everything, are too close without any edge. But what if she can’t see the trees for the wood – only the big picture and no detail, a single mass of forest but not a single tree. How would you know what a forest is made from? The importance of being able to oscillate between the two is significant to understanding: seeing both forest and trees.

(viii) Blown up, Sweet Stag, curled up in the corner on a small green mound, gentle cross-stitch gives the 3-inch animal enough structure to hold him. But then BOOM, expanded to life size he encounters difficulty in both the stitch and the animal; he does not like to grow. Pixelated now beyond his appealing smaller self a grotesque creature is formed. From far off he still retains a trace of his smaller self but as you approach this begins to falter. Oscillating between a stitch, a pixel, a line, a thread the Stag is mimicking as best he can. But up close he disinte- grates back into the component units that make him up.

Transformation through Repetition

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going repeatedly around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So it adapts, mimics, copies, the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(ix) Words and letters dissolving into pattern, repeated again and again. Pattern and line accumulate into words, repeated over and over. The action of making embedded; repeating a line, a word, a letter. Focusing on drawing a single letter annexes it form the word, dissipating meaning.

(iii) But what of these trees – is this all one sees? How about further details found in those woods: bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee, bee. But then looking too closely, nothing is seen . . . . . it dissipates into pixels. But what is that pixel, a beautiful stitch, a mark. Step back to see the whole and the detail disappears, move closer and the whole vanishes. When no detail is there, guess-work and structure are laid in place where the image usually is. Back and forth until perhaps something is captured, held onto, made real.

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So it adapts, mimics, copys, duplicates, replicates, clones, fakes, counterfeits, impersonates, simulates, mirrors, echos, parallels, retells, recites, restates, iterates, the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

Fractal Processes or Unit versus Whole

(ii) Can’t see the wood for the trees. Living in a log cabin in the American outback, she can’t see the wood for the trees; she is blind to anything but the forest, blinded by the forest. The trees permeate everything, are too close without any edge. But what if she can’t see the trees for the wood – only the big picture and no detail, a single mass of forest but not a single tree. How would you know what a forest is made from? The importance of being able to oscillate between the two is significant to understanding: metaphorically seeing both forest and trees.

(viii) Blown up, Sweet Stag, curled up in the corner on a small green mound, gentle cross-stitch gives the 3-inch animal enough structure to hold him. But then, expanded to life size he encounters difficulty in both the stitch and the animal; he does not like to grow. Pixelated now beyond his appealing smaller self a grotesque creature is formed. From far off he still retains a trace of his smaller self but as you approach this begins to falter. Oscillating between a stitch, a pixel, a line, a thread – the Stag is mimicking as best he can. But up close he disintegrates back into the component units that make him up.

(iii) Now flipping back to metaphorically seeing of just the trees – is this all one sees? How about further details found in those woods: the bear, fox, birds, squirrel, leaf, flower, bee, ant. But then looking too closely, nothing is seen . . . . . it dissipates into pixels. But what is that pixel, a beau- tiful stitch, a mark. Step back to see the whole and the detail disappears, move closer and the whole vanishes. When no detail is there, guess-work and structure are laid in place where the image usually is. Back and forth until perhaps something is captured, held onto, made real.

(iv) Similar to a fractal process of zooming in and out of the work: the viewer steps back for the long overview, moving closer for the individual view, further in for a detail view and so on. This is comparable to the experience of a site itself; like the fractal zooming in and zooming out of each layer {whether it be a building, room, wall, installation, artwork, object, image, line, stitch, mark, dot} each is new and unique yet all telling a similar story.

Labour (Action, Making, Boredom, Muscle Memory, Sex)

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around and around and around and around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So it adapts, mimics, copies the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio} and my grand- father taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or her studio, as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around and around and around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So, it adapts, mimics, copies the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(i) Subtle slippages between the expected, minor moments found in the and goings of everyday life, discovered only through close observation, looking again. Attention and curiosity are needed to uncover these moments. Only through investing time and truly looking are details revealed. Hidden in plain sight, the domestic {whether pattern or object} is so familiar we (don’t) forget to look at it. To really look, to pay attention to what is in front of us all the time. It sees you, but do you see it?

(ii) Can’t see the wood for the trees. Living in a log cabin in the American outback, she can’t see the wood for the trees; she is blind to anything but the forest, blinded by the forest. The trees permeate everything, are too close without any edge. But what if one can’t see the trees for the wood – only the big picture and no detail, a single mass of forest but not a single tree. How would you know what a forest is made from? The importance of being able to oscillate between the two is significant to understanding: seeing both forest and trees.

(iii) But what of these trees – is this all one sees? How about further details found in those woods: the bear, fox, bird, squirrel, leaf, flower, bee, ant. But then looking too closely, nothing is seen . . . . . it dissipates into pixels. But what is that pixel, a beautiful stitch, a mark. Step back to see the whole and the detail disappears, move closer and the whole vanishes. When no detail is there, guess-work and structure are laid in place where the image usually is. Back and forth until perhaps something is captured, held onto, made real.

(iv) Similar to a fractal process of perspective zooming in and out of the work: the viewer steps back for the long overview, moveing closer for the individual view, further in for a detail view and so on. This is comparable to the experience of site itself; like the fractal zooming in and zooming out of each layer {whether it be a building, room, wall, installation, artwork, object, image, line, stitch} is new and unique yet all telling a similar story.

(v) Flowing, between meaning and image the repetition of drawn words transforms them into the visual. Similar to calligraphy the textlines are intended to be visual while retaining some legi- bility. Fluxing between meaning and image the textlines are meant to ‘convey complexities of content without necessarily always spelling out the content for the viewer.’

(vi) The pencil cannot be like the stitched line going around and around the page; its line is not attached like thread to a needle. So, it adapts, mimics, copies the stitched line: impersonation is never easy, it needs many tricks to mimic the original. Complex lines and time are needed to tackle similar marks found in stitch.

(vii) My grandmother taught me the love of making in her sewing room {or studio as I now like to think of it} and my grandfather taught me calligraphy. Such enjoyment in the action of forming letter shapes and word forms; writing letters over and over again, to feel their twirl. {A habit I still have, margins of notes filled with individual repeated letters.} Writing that isn’t about writing but the visuals of text; think about how fonts can change ones reading of the content. My grandfather was an intelligent man but unable to afford university he instead took one semester of handwriting. If he could not be education, he could at least look it.

(viii) Blown up, Sweet Stag, curled up in the corner on a small green mound, gentle cross-stitch gives the 3-inch animal enough structure to hold him. But then BOOM, expanded to life size he encounters difficulty in both the stitch and the animal; he does not like to grow. Pixelated now beyond his appealing smaller self a grotesque creature is formed. From far off he still retains a trace of his smaller self but as you approach this begins to falter. Oscillating between a stitch, a pixel, a line, a thread the Stag is mimicking as best he can. But up close he disintegrates back into the component units that make him up.

(ix) Words and letters dissolve into pattern, repeated again and again. Pattern and line accumulate into words, repeated over and over. The action of making embedded; repeating a line, a word, a letter. Focusing on drawing a single letter annexes it form the word, dissipating meaning.

Image details

Four Glory Holes, 2007, pencil drawing on Mylar mounted on aluminium.

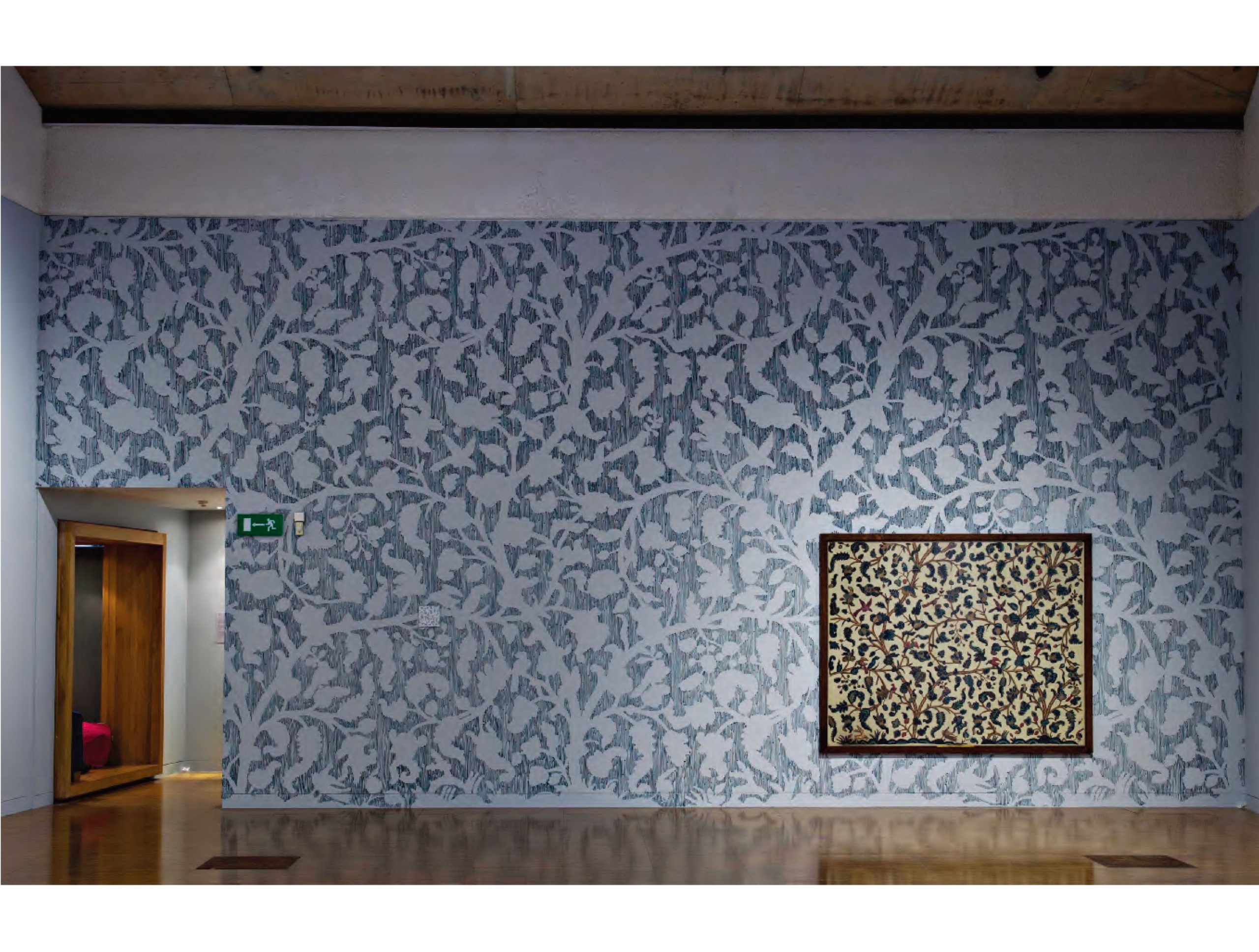

Nest with Pigeon Hole and Blue Tit, 2014, 5m x 10m, wall painting, Jacobean Bedspread, drawing on

Mylar, The Collection Museum, Lincoln.

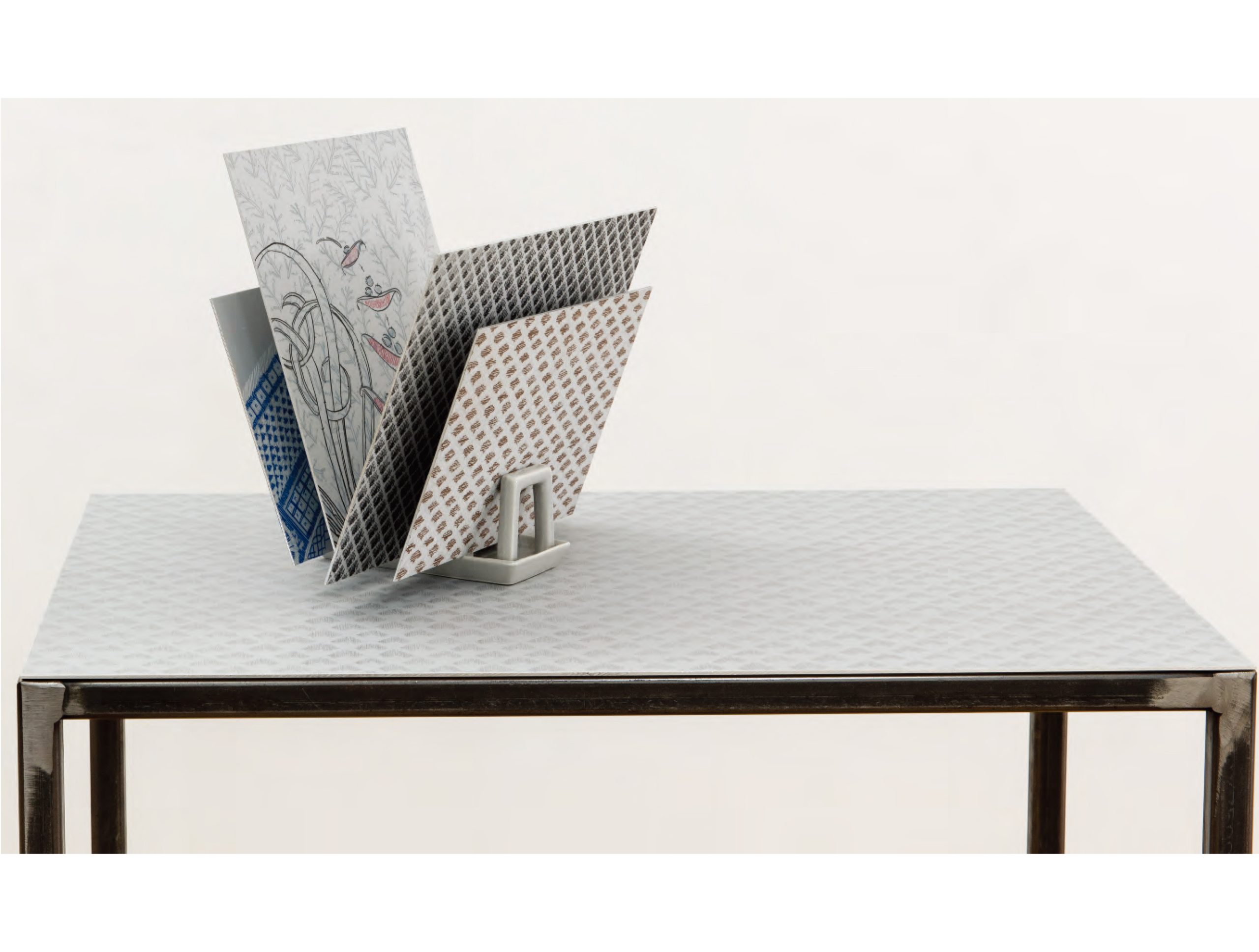

Nesting: Milker, 2018, steel frame, aluminium, Mylar, coloured pencil, ceramic toast rack.

Pussy Willow Mountains, 2016, pencil drawing on Mylar, mounted on aluminium and emulsion paint, Sheffield Institute of Art Gallery, Sheffield.

Acknowledgements

The writing has been adapted and rewritten into this new performative text. The originals can be found in:

Maier, Danica (2015),‘Forsaken Decoration’, in N. Brownsword and A. H. Mydland (eds), Topographies of the Obsolete: Site Reflections, Stoke on Trent: Topographies of the Obsolete, pp. 86–91.

Maier, Danica (2016), ‘Line on Line’, in D. Maier, Grafting Propriety: From Stitch to the Drawn Line, London: Black Dog Publishing, pp. 105–107.

Suggested citation

Maier, D. (2019),‘Looking Again’, Journal of Illustration, 6:1, pp. 183–204, doi: 10.1386/jill_00010_1

Contributor details

Danica Maier’s practice uses drawing, site-specific installations, and objects to explore expectations, while using subtle slippages to transgress propriety. She is an Associate Professor in Fine Art at Nottingham Trent University, where she runs an artists’ residency, the Summer Lodge.

E-mail: danica.maier@ntu.ac.uk

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1738-2001

Danica Maier has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work in the format that was submitted to Intellect Ltd.