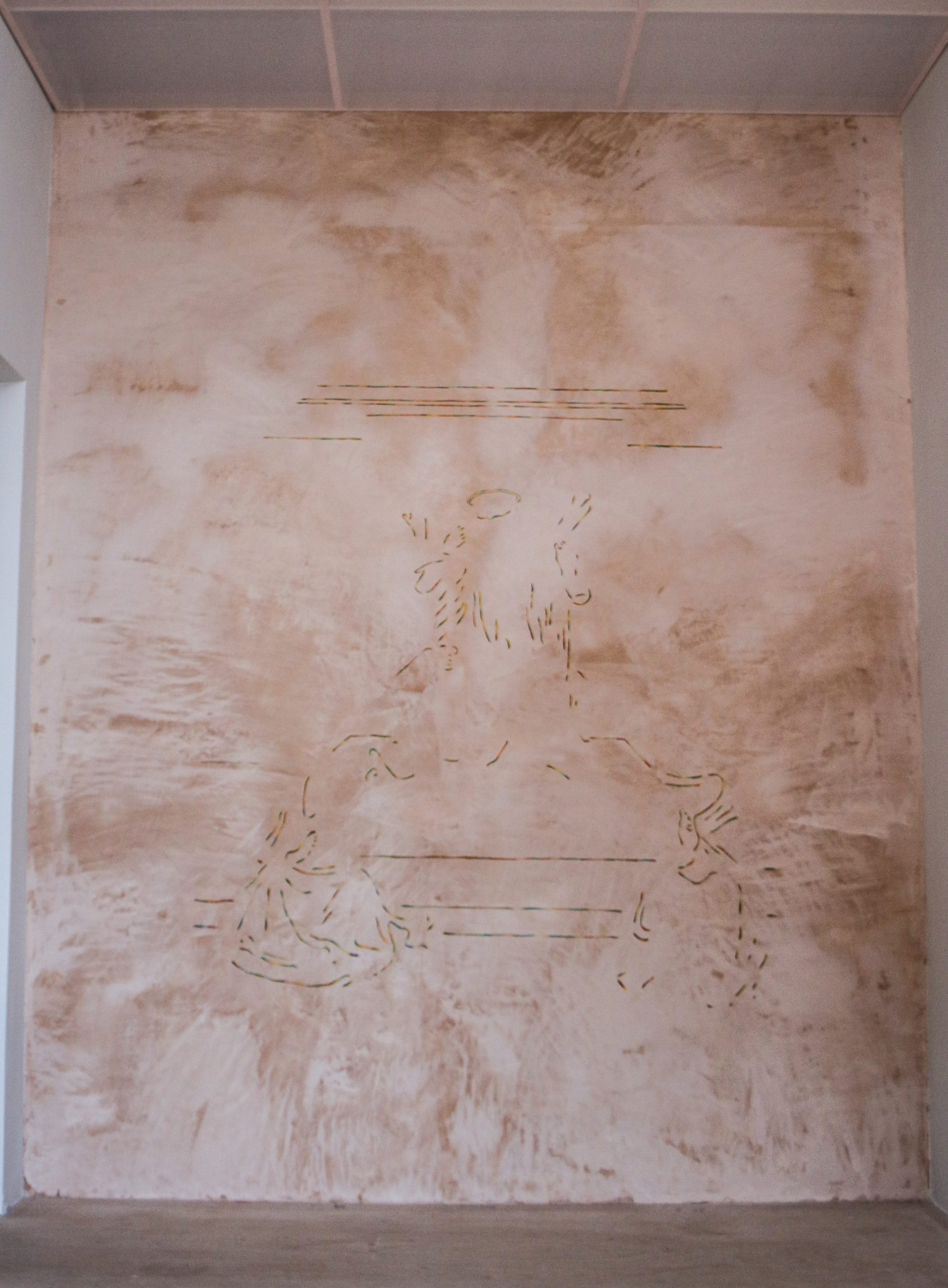

i Qui Vive is a term for heightened watchfulness, vigilance or preparation for action; a state of being especially watchful and alert. Qui Vive is also a series of paintings made after a sustained period of looking attentively at Fra Angelico’s The Mocking of Christ (1441). I transcribe elements of the original painting in the form of coloured lines directly onto the gallery wall.

ii Vija Celmins speaks of how: “The paintings I like to see have a compacted time that opens your eyes. When you pack a lot of time into a work, something happens that slows the image down, makes it more physical, makes you stay with it.”17 Celmins implicitly understands strange relationships with time that are connected in the encounter with a painting, precisely because she is a painter. Celmins’ notion of compacted time is pertinent to what an artist may notice in an artwork that others might not notice, or feel is significant – what I pick out in The Mocking of Christ for each Qui Vive for example. Celmins also talks of the millions of decisions that go into making a piece of work, to gives a “personal identity that develops over painting it, many times and it gives it a certain kind of presence.”18 Choices in the time of making can be understood to be compressed into the viewing of a work.

iii After spending time close looking at a reproduction, elements of The Mocking of Christ are partially transcribed in the form of lines in the same position as the original composition. The line shifts and changes as you get closer to the painting, from afar the line can appear to be monochrome, as you get closer the lines pulse with multiple colours, akin to the splitting of light by the prism. Missing elements of the original concurrently allow space for the imagination or memory to be (re) ignited. Each Qui Vive is made in the here and now; I try not to consider previous versions, whilst simultaneously recognising that each of these will inevitably impact on the decisions of each new painting. Time mutates beyond the rigidity of clocktime, becoming nebulous. I wonder what it means to stare, instead of to see or look at a work of art? A stare can be perceived as rude, unsettling, off-putting. To stare is neither quick nor slight, but allows focus and intensity; it can also be to zone out, to allow the subconscious in. Susan Sontag writes that: “Traditional art invites a look. Art that’s silent engenders a stare. In silent art, there is (at least in principle) no release from attention, because there has never, in principle, been any soliciting of it.”19 The stare, like the silent art Sontag speaks of, is something active and present, but also something elusive – felt in the gut, heart and eyes as much as the brain. I aspire for Qui Vive to allow someone to just be in the moment with it.

iv The intention of Qui Vive is twofold. The making process creates a dialogue across time with Fra Angelico’s fresco. I engage a sort of muscle-memory by repeatedly imprinting the image and memory of the painting; this also connects to my aphantasia – the inability to remember or think visually20. The viewing process encourages close looking of painting, my own and Fra Angelico’s. Qui Vive departs from the traditions of the transcription through a balancing act of retaining and erasing the original painting; Qui Vive fails if one aspect is too dominant. The activity and direction of how the knowledge is gathered and articulated relies on felt and tacit knowledge, in this case, garnered through the habitus of the artist.

v The only time I have seen Fra Angelico’s frescoes was during an A-level trip to Florence in 1995. On the penultimate day we were driven by coach to yet another old building, the San Marco convent.

My friends raced around and left to go shopping. Meanwhile I had a sliding doors experience. I stopped transfixed at the top of the stone stairs, enthralled by Fra Angelico’s Annunciation (1438-45) that faced me. Time slowed down, I could have stayed there all day, a lifetime. Any shred of teenage cool disappeared, replaced by love at first sight. The awe of this experience only intensified as I moved from along the corridors, from monk cell to cell to encounter masterpiece upon masterpiece. I was guided by my history teacher Mr Derrick, who was clearly surprised and delighted by my enthusiasm. The Mocking of Christ was the single piece that captured me most then, and now. I did not know that art could do make me feel this way. I hunger for repeats of this experience.

vi Qui Vive is made with an intent for two-way dialogue between painting and painter, allowing mutualist influence to occur. Fra Angelico’s work influences me in the present and I seek to give influence back to it; The Mocking of Christ can change, because of Qui Vive, this is a fundamental position of the ‘parasitical painter’21. I give agency back to The Mocking of Christ, rather than taking from it, allowing a rich vocabulary of action to occur. Art historian Michael Baxandall writes that when we respond to an existing painting, we “draw on, resort to, avail oneself of, appropriate from, have recourse to, adapt, misunderstand, refer to, pick up, take on, engage with, react to, quote, differentiate oneself from, assimilate oneself to, assimilate, align oneself with, copy…”22 These sentiments cannot be reversed, Fra Angelico cannot influence me in these ways.

vii The process of looking at a work of art oscillates between past and present, and in this case between The Mocking of Christ and Qui Vive. The curious part of this is that all art is contemporary, after all the art happens in the encounter in the present. An oscillation of distinct times starts to eat itself in the present.

viii Philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti writes: “When you are looking at something with complete attention there is no space for a conception, a formula or a memory. This is important to understand because we are going into something which requires very careful investigation. It is only a mind that looks at a tree or the stars or the sparkling waters of a river with complete self-abandonment that knows what beauty is, and when we are actually seeing we are in a state of love.”23 Qui Vive is made in a state of complete attention and love towards Fra Angelico’s fresco.

ix Meanwhile, philosopher Byung-Chul Han has talked of how our contemporary culture desires new stimuli and is increasingly steeped in attention deficit disorder-like tendencies. Han speaks of a loss in the human capacity to linger and a tendency to overlook the value in the past. He sees this as being linked to a move away from ritual and religious practices that encourage deep attention. Han speaks of how within repetition in rituals, “past and present are brought together into a living present. As a form of completion, repetition founds duration and intensity. It ensures that time lingers.”24 In Qui Vive the repeatedly painted lines of the details of The Mocking of Christ evoke a ritual-like mediative state of awareness in the present. Artist Agnes Martin writes: “The artist uses only the primary awareness because the intellect draws on knowledge from the past which leads us in a circle. The response in primary awareness is in feeling. The response to art is feeling not intellectual (knowledge) or emotional love, anger, etc, but pure feelings such as you would have at the beach–freedom, joy, gratitude, innocence, harmony, content, the sublime, all positive feeling.”25 I value linked notions of curiosity, tacit knowledge and imagination, over rationality, definite answers and certainty. Connectively philosopher Michelle Boulous Walker talks of the activity of slow and careful reading can be “an intellectual curiosity rather than a deferential account; as a questioning rather than an explanation; as an incomplete reading rather than a final one; as a partial account rather than an exhaustive one; as a suspended judgement rather than a verdict….”26 In making, and asking others to view, Qui Vive, I encourage a switch from desiring answers, towards noticing what is felt through primary awareness in the encounter with an artwork.

x The historical, theoretical, and semiotic context of the work are not side-lined, but are supplemented (overshadowed perhaps) by readings of the work that are driven by notions of the periphery, materiality, textures, colour, line, etc. The attentiveness of the artist drives Qui Vive.

xi There is focus away from the overall composition towards highlights and details, the eye is encouraged to wander. The methodology of the work allows echoes of the original paintings to be retained, whilst creating the room for other possibilities and readings.

xii Qui Vive began in Spring 2020 during the lockdown caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. I felt a kinship between my temporal state of isolation at home and painting as a form of devotion. Fra Angelico was said to believe that he was merely a vessel for God and that his paintings were actually made by God. Nothing was ever changed in his paintings once a mark was put down, as to do so would be to doubt God. Similarly, once I decide on the details to be picked out in the watercolour lines, there can be no change to it, no going back. To do so would be to doubt what is felt in the moment.

Andrew Bracey.

17. Vija Celmins and Jeanne Silverthorne, ‘Vija Celmins in Conversation with Jeanne Silverthorne’, Parkett, no. 44 (1995), p42.

18. Tate, ‘Explore the Art of Vija Celmins – Look Closer’, Tate, accessed 23 August 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/ artists/vija-celmins-2731/vija-celmins-artist-rooms.

19. Susan Sontag, Styles of Radical Will (London: Penguin Classics, 2009), p16.

20. Andrew Bracey, ‘Painting Aphantasia: Making The Non-Visible, Visible’, in Photography Digital Painting, ed. Carl Robinson, (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020), 99–122.

21. Andrew Bracey, ‘Parasitical Paintings’, Journal of Contemporary Painting 4, no. 2 (1 October 2018): 325–44, https://doi.org/10.1386/jcp.4.2.325_1.

22. Michael Baxandall, Patterns of Intention: On the Historical Explanation of Pictures, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), p59.

23. Jiddu Krishnamurti, Freedom from the Known (London: Rider, 2010), p92.

24. Byung-Chul Han, The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present, trans. Daniel Steuer, (Cambridge: Polity, 2020), p8.

25. Nancy Princenthal, Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art, 1st edition (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2015), p210.

26. Michelle Boulous Walker, Slow Philosophy: Reading Against the Institution (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), p33.

Qui Vive The Mocking of Christ. Watercolour on Plaster, 2021. Installation at General Practice, Lincoln. Photograph – Georgia Preece

Self-ish Portraits. Oil on canvas. 2021.