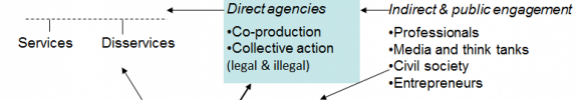

Our framework is founded upon the central assumption that access/exposure to ecosystem services/risks for the urban poor is institutionally-mediated. Mediation is articulated through three linked concepts: urban ecosystems; political ecology of urban change; and institutional diversity (Figure 1). At the city/national level, the dominant political ecology ideology influences how the state defines the legal and political framework for managing urban ecosystems, as well as modalities for producing and distributing basic services to the poor and preventing ecosystems disservices. Urban ecosystems are in constant change, influenced by development opportunities (e.g. increased industrial activities due to globalisation) and challenges (e.g. global financial crisis). The institutional modalities that translate these changes into services for poor people involve diverse actors at multiple levels, including government, private, non-governmental and community-based organisations (Agrawal, 2010). In practice, however, the urban poor rely predominantly on their own collective action, with some co-production. Success depends upon their solidarity, particularly with regards to collective action. They also benefit from the evolution of co-productive behaviours and practices, selective incentives, entrepreneur behaviours, and information from media and think-tanks, through indirect transfer of knowledge and expertise (John, 2003).

Figure 1: Analytical Framework

To elaborate how these three concepts will help us examine the research questions, we build the following additional insights based on contemporary literature:

The political ecology of urban change is a theoretical platform for interrogating the interrelated socio-ecological processes occurring within cities (Heynen et al., 2006). It reflects the decisions that societies make, or fail to make, about the urban environment in the context of their political environment, development opportunities and challenges, and patterns of resource distribution (Monstadt, 2009). The concept contends that there are social and political explanations as to why the urban poor have sub-optimal levels of access to green and water ecosystem services and greater exposure to disservices. Gandy (2008) illustrates this through his study of the resistance that Mumbai Municipal Authority’s good intentions to improve sanitation in slum communities met from private providers, who were making money out of existing poor sanitation conditions.

The concept of institutional diversity recognises that the sustainability of ecosystem processes and the derived services requires a variety of institutions operating at multiple levels (Ostrom, 2005). In regards to low-income settlements, it is useful to distinguish between direct and indirect agencies. Direct agencies are those with contextual attachments (e.g. grassroots organisations), duty concerns (e.g. municipal governments; NGOs; political elites) or market links (e.g. private entrepreneurs; economic elites) with the urban poor. Various incentives and trade-offs work as enablers for grassroots organisations to form collective action and, where available, to engage in co-productive arrangements with other direct agencies. Orangi Pilot Project in Karachi (Hasan, 2008) is one well-known examples in this regard. Indirect agencies, on the other hand, play important roles of advocacy, knowledge production and dissemination, and public awareness raising of the needs of low-income people. This can influence the activities of direct agencies across the city space, as Barthel et al. (2013) show in the context of ‘Ecopark’ in Stockholm. Both direct and indirect agencies can support low-income people to secure ecosystem services and/or avoid risk of disservices. The urban poors’ links are stronger with the grassroots organisations they are part of, but these links are strongly influenced by; their structural attributes (age, gender, education etc.); settlement size, age and location; and their tenure status (home owners in authorised slums; tenants etc) (Roy et al., 2013).

These concepts enable us to focus on three aspects that correspond to our three secondary research questions. First, the urban ecosystems concept helps us to focus on fundamental services and exposure to health risks from urban green and water structures as key elements representing people’s basic needs. Secondly, the political ecology concept helps us understand poor people’s existing levels of access to services and/or exposure to risks as socially-constructed. Thirdly, the institutional diversity concept helps us consider people’s collective action as just one, but significant, component of the social production of ecosystem services. We must analyse collective action in a context of complex power relations involving diverse actors, where co-production may or may not occur. A lot is dependent on the profiles of people, place and politics.